Goitre

| Goitre | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Endocrinology, nuclear medicine |

A goitre or goiter (Latin gutteria, struma), also called a bronchocele, is a swelling in the thyroid gland,[1] which can lead to a swelling of the neck or larynx (voice box). Goitre usually occurs when the thyroid gland is not functioning properly.

Classification

They are classified in different ways:

- A "diffuse goitre" is a goitre that has spread through all of the thyroid (and can be a "simple goitre", or a "multinodular goitre").

- "Toxic goitre" refers to goitre with hyperthyroidism. These are most commonly due to Graves' disease, but can be caused by inflammation or a multinodular .

- "Nontoxic goitre" (associated with normal or low thyroid levels) refers to all other types (such as that caused by lithium or certain other autoimmune diseases).

Other type of classification:

- Class I - palpation struma - in normal posture of the head, it cannot be seen; it is only found by palpation.

- Class II - the struma is palpative and can be easily seen.

- Class III - the struma is very large and is retrosternal; pressure results in compression marks.

Signs and symptoms

In general, goitre unassociated with any hormonal abnormalities will not cause any symptoms aside from the presence of anterior neck mass. However, for particularly large masses, compression of the local structures may result in difficulty in breathing or swallowing. In those presenting with these symptoms, malignancy must be considered.

Meanwhile, toxic goitres will present with symptoms of thyrotoxicosis such as palpitations, hyperactivity, weight loss despite increased appetite, and heat intolerance.

Causes

Worldwide, the most common cause for goitre is iodine deficiency. In countries that use iodized salt, Hashimoto's thyroiditis is the most common cause. [2]

Other causes are:overproduction or unproduction of hormones [citation needed]

Hypothyroid

- Inborn errors of thyroid hormone synthesis, causing congenital hypothyroidism (E03.0)

- Ingestion of goitrogens, such as cassava.

- Side-effects of pharmacological therapy (E03.2)

Hyperthyroid

- Graves' disease (E05.0)

- Thyroiditis (acute or chronic) (E06)

- Thyroid cancer

Treatment

Treatment may not be necessary if the goitre is small. Goitre may be related to hyper- and hypothyroidism (especially Graves' disease) and may be reversed by treatment. Graves' disease can be corrected with antithyroid drugs (such as propylthiouracil and methimazole), thyroidectomy (surgical removal of the thyroid gland), and iodine-131 (131I - a radioactive isotope of iodine that is absorbed by the thyroid gland and destroys it). Hypothyroidism may raise the risk of goitre because it usually increases the production of TRH and TSH. Levothyroxine, used to treat hypothyroidism, can also be used in euthyroid patients for the treatment of goitre. Levothyroxine suppressive therapy decreases the production of TRH and TSH and may reduce goitre, thyroid nodules, and thyroid cancer. Blood tests are needed to ensure that TSH is still in range and the patient has not become subclinically hyperthyroid. If TSH levels are not carefully monitored and allowed to remain far below the lower limits of normal (below 0.1 mIU/L or IU/mL), there is epidemiologic evidence that levothyroxine may increase the risk of osteoporosis and both hip and spinal fractures.[3]. (Such low levels are therefore not intentionally produced for long periods, except occasionally in the treatment of TSH-dependent thyroid cancers.)

Thyroidectomy with 131I may be necessary in euthyroid goitrous patients who do not respond to levothyroxine treatment, especially if the patients have difficulty breathing or swallowing. 131I, with or without the pre-injection of synthetic TSH, can relieve obstruction and reduce the size of the goitre by thirty to sixty-five percent. Depending on how large the goitre is and how much of the thyroid gland must be removed or destroyed, thyroidectomy and/or 131I treatment may destroy enough thyroid tissue as to produce hypothyroidism, requiring life-long treatment with thyroid hormone pills.

Epidemiology

Iodine is necessary for the synthesis of the thyroid hormones thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). In endemic goitre, iodine deficiency leaves the thyroid gland unable to produce its hormones because the mature hormone molecules require iodine atoms to be attached. When levels of thyroid hormones fall, thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) is produced by the hypothalamus. TRH then prompts the pituitary gland to make thyrotropin or thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), which stimulates the thyroid gland’s production of T4 and T3. It also causes the thyroid gland to grow in size by increasing cell division.

Goitre is more common among women, but this includes the many types of goitre caused by autoimmune problems, and not only those caused by simple lack of iodine.

Some researchers [5] showed a correlation between Iodine-deficient goitre and gastric cancer, and reported in goitrous territories a decrease of the incidence of goitre and of stomach cancer after implementation of iodine-prophylaxis.[6] The proposed mechanism of action is that iodide ion (I-) can function in thyroid gland and in gastric mucosa as an antioxidant [7] reducing species that can detoxify poisonous reactive oxygen species, such as hydrogen peroxide.

History

Chinese physicians of the Tang Dynasty (618–907) were the first to successfully treat patients with goitre by using the iodine-rich thyroid gland of animals such as sheep and pigs—in raw, pill, or powdered-mixture-in-wine form.[8] This was outlined in Zhen Quan's (d. 643 AD) book, as well as several others.[9] One Chinese book (i.e. The Pharmacopoeia of the Heavenly Husbandman) asserted that iodine-rich sargassum was used to treat goitre patients by the 1st century BC, but this book was written much later.[10]

In the 12th century, Zayn al-Din al-Jurjani, a Persian physician, provided the first description of Graves' disease after noting the association of goitre and exophthalmos in his Thesaurus of the Shah of Khwarazm, the major medical dictionary of its time.[11][12] Al-Jurjani also established an association between goitre and palpitation.[13] The disease was later named after Irish doctor Robert James Graves,[14] who described a case of goitre with exophthalmos in 1835. The German Karl Adolph von Basedow also independently reported the same constellation of symptoms in 1840, while earlier reports of the disease were also published by the Italians Giuseppe Flajani and Antonio Giuseppe Testa, in 1802 and 1810 respectively,[15] and by the English physician Caleb Hillier Parry (a friend of Edward Jenner) in the late 18th century.[16]

Paracelsus (1493–1541) was the first person to propose a relationship between goitre and minerals (particularly lead) in drinking water.[17] Iodine was later discovered by Bernard Courtois in 1811 from seaweed ash.

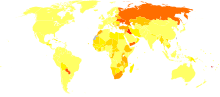

Goitre was previously common in many areas that were deficient in iodine in the soil. For example, in the English Midlands, the condition was known as Derbyshire Neck. In the United States, goitre was found in the Great Lakes, Midwest, and Intermountain regions. The condition now is practically absent in affluent nations, where table salt is supplemented with iodine. However, it is still prevalent in India, China[18] Central Asia and Central Africa.

Society and culture

Famous goitre sufferers

- Edward Gibbon

- Kim Il-Sung

- Former President George H. W. Bush and his wife Barbara Bush both were diagnosed with Graves' disease and goitres, within two years of each other. In the president's case, the disease caused hyperthyroidism and cardiac dysrhythmia.[19][20][21][22] Scientists said that the odds of both George and Barbara Bush having Graves’ disease might be 1 in 100,000 or as low as 1 in 3,000,000[23]

- Andrea True (according to an interview on VH1)[24]

- Umm Kulthum, a famous Egyptian singer, refused to undergo surgical treatment for fear of accidental injury of laryngeal nerves.

See also

- Struma ovarii (a kind of teratoma)

- David Marine conducted substantial research on the treatment of goitre with iodine.

- Endemic goitre

- Graves' Disease (also known as Exophthalmic goiter or Basedow's disease)

References

- ^ "goiter" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ Mitchell, Richard Sheppard; Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson. Robbins Basic Pathology. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-2973-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) 8th edition. - ^ Annals of Internal Medicine 2001;134:561-568, 3 April 2001 Volume 134 Number 7

- ^ "Mortality and Burden of Disease Estimates for WHO Member States in 2002" (xls). World Health Organization. 2002.

- ^

Abnet CC, Fan JH, Kamangar F; et al. (2006). "Self-reported goiter is associated with a significantly increased risk of gastric noncardia adenocarcinoma in a large population-based Chinese cohort". Int. J. Cancer. 119 (6): 1508–10. doi:10.1002/ijc.21993. PMID 16642482.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Venturi S, Venturi A, Cimini D, Arduini C, Venturi M, Guidi A (1993). "A new hypothesis: iodine and gastric cancer". Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2 (1): 17–23. doi:10.1097/00008469-199301000-00004. PMID 8428171.{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Venturi S, Donati FM, Venturi A, Venturi M, Grossi L, Guidi A (2000). "Role of iodine in evolution and carcinogenesis of thyroid, breast and stomach". Adv Clin Path. 4 (1): 11–7. PMID 10936894.{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Gołkowski F, Szybiński Z, Rachtan J; et al. (2007). "Iodine prophylaxis--the protective factor against stomach cancer in iodine deficient areas". Eur J Nutr. 46 (5): 251–6. doi:10.1007/s00394-007-0657-8. PMID 17497074.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^

Venturi S, Venturi M (1999). "Iodide, thyroid and stomach carcinogenesis: evolutionary story of a primitive antioxidant?". Eur. J. Endocrinol. 140 (4): 371–2. doi:10.1530/eje.0.1400371. PMID 10097259.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

- ^ Temple, Robert. (1986). The Genius of China: 3,000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention. With a forward by Joseph Needham. New York: Simon and Schuster, Inc. ISBN 0671620282. Pages 133–134.

- ^ Temple, Robert. (1986). The Genius of China: 3,000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention. With a forward by Joseph Needham. New York: Simon and Schuster, Inc. ISBN 0671620282. Page 134.

- ^ Temple, Robert. (1986). The Genius of China: 3,000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention. With a forward by Joseph Needham. New York: Simon and Schuster, Inc. ISBN 0671620282. Pages 134–135

- ^ Basedow's syndrome or disease at Who Named It? - the history and naming of the disease

- ^ Ljunggren JG (1983). "[Who was the man behind the syndrome: Ismail al-Jurjani, Testa, Flagani, Parry, Graves or Basedow? Use the term hyperthyreosis instead]". Lakartidningen. 80 (32–33): 2902. PMID 6355710.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Nabipour, I. (2003). "Clinical Endocrinology in the Islamic Civilization in Iran". International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1: 43–45 [45].

- ^ Robert James Graves at Who Named It?

- ^ Giuseppe Flajani at Who Named It?

- ^ Hull G (1998). "Caleb Hillier Parry 1755-1822: a notable provincial physician". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 91 (6): 335–8. PMC 1296785. PMID 9771526.

- ^ "Paracelsus" Britannica

- ^ "In Raising the World’s I.Q., the Secret’s in the Salt", article by Donald G. McNeil, Jr., December 16, 2006, New York Times

- ^ The Health and Medical History of President George Bush DoctorZebra.com. 8 August 2004. Retrieved 8 October 2006.

- ^ "George H.W. Bush." NNDB.

- ^ Robert G. Lahita and Ina Yalof. Women and Autoimmune Disease: The Mysterious Ways Your Body Betrays Itself. Page 158.

- ^ Lawrence K. Altman, M.D. “Doctors Say Bush Is in Good Health.” The New York Times. September 14, 1991.

- ^ Lawrence K. Altman, M.D. “The Doctor’s World; A White House Puzzle: Immunity Ailments.”, The New York Times. May 28, 1991]

- ^ “Andrea True.” Elle.

External links

- National Health Services, UK

- Network for Sustained Elimination of Iodine Deficiency

- Network for Sustained Elimination of Iodine Deficiency - alternate site at Emory University's School of Public Health

- A case and photograph of a huge goitre from Photobucket.com and Doctorkhodadoust.net

This template is no longer used; please see Template:Endocrine pathology for a suitable replacement Template:Link GA