Naegleriasis: Difference between revisions

Ilovededede (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

m →United States: scientific convention |

||

| Line 83: | Line 83: | ||

* In August 2005, two Oklahoma boys, ages seven and nine, were killed by ''N. fowleri'' after swimming in the hot, stagnant water of lakes in the Tulsa area.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://health.dailynewscentral.com/content/view/1448/63 |title=Parasitic Infection Kills Two Tulsa Swimmers |accessdate=2005-08-06 }}</ref> |

* In August 2005, two Oklahoma boys, ages seven and nine, were killed by ''N. fowleri'' after swimming in the hot, stagnant water of lakes in the Tulsa area.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://health.dailynewscentral.com/content/view/1448/63 |title=Parasitic Infection Kills Two Tulsa Swimmers |accessdate=2005-08-06 }}</ref> |

||

* In 2007, six cases were reported in the U.S., all fatal.<ref name=MMWR2008/><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cnn.com/2007/HEALTH/10/04/amoeba.lake/index.html | title=Rare but deadly amoeba infection hard to predict |accessdate=2012-10-10 }}</ref> |

* In 2007, six cases were reported in the U.S., all fatal.<ref name=MMWR2008/><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cnn.com/2007/HEALTH/10/04/amoeba.lake/index.html | title=Rare but deadly amoeba infection hard to predict |accessdate=2012-10-10 }}</ref> |

||

* August 2010, 7 year old Kyle Lewis died from the brain-eating amoeba Naegleria |

* August 2010, 7 year old Kyle Lewis died from the brain-eating amoeba ''Naegleria fowleri'' after swimming in fresh water in Texas. <ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.livescience.com/15645-brain-eating-amoeba.html | title=Family Warns Swimmers About Brain-Eating Amoeba}}</ref> www.KyleCares.org |

||

==Public health prevention strategies== |

==Public health prevention strategies== |

||

Revision as of 03:47, 9 December 2012

| Naegleria fowleri | |

|---|---|

| |

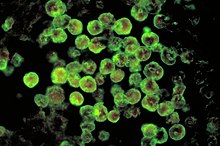

| Different stages of Naegleria fowleri | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | N. fowleri

|

| Binomial name | |

| Naegleria fowleri Carter (1970)

| |

Naegleria fowleri (/[invalid input: 'icon']nəˈɡlɪəriə/) (also known as the brain-eating amoeba) is a free-living excavate form of protist typically found in warm bodies of fresh water, such as ponds, lakes, rivers, and hot springs. It is also found in soil, near warm-water discharges of industrial plants, and unchlorinated or poorly chlorinated swimming pools in an amoeboid or temporary flagellate stage. There is no evidence of this organism living in ocean (salt) water. Rarely, it can appear in inadequately treated samples of home-based tap water that is not treated enough to be entirely potable, though this is not the usual method of contracting the illness unless the water is very deeply inhaled, usually deliberately. It is an amoeba belonging to the groups Percolozoa or Heterolobosea.

N. fowleri can invade and attack the human nervous system. Although this occurs rarely,[1] such an infection nearly always results in the death of the victim.[2] The case fatality rate is estimated at 98%.[3]

History of discovery

Physicians M. Fowler and R. F. Carter first described human disease caused by ameboflagellates in Australia in 1965.[4] Their work on ameboflagellates has provided an example of how a protozoan can effectively live both freely in the environment, and in a human host. Since 1965, more than 144 cases have been confirmed in a variety of countries. In 1966, Fowler termed the infection resulting from N. fowleri primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (P.A.M.) to distinguish this central nervous system (C.N.S.) invasion from other secondary invasions caused by other true amoebas such as Entamoeba histolytica.[5] A retrospective study determined the first documented case of P.A.M. possibly occurred in Britain in 1909.[6]

Life cycle

Naegleria fowleri occurs in three forms: a cyst, a trophozoite (ameboid) and a flagellate.

- Cyst stage

Trophozoites encyst due to unfavorable conditions. Factors that induce cyst formation can include food deprivation, crowding, desiccation, accumulation of waste products, and cold temperatures.[7] N. fowleri has been found to encyst at temperatures below 10°C.[8]

- Trophozoite stage

This reproductive stage of the protozoan organism, which transforms near 25°C and grows fastest at around 42°C, proliferates by binary fission. The trophozoites are characterized by a nucleus and a surrounding halo. They travel by pseudopodia, temporary round processes which fill with granular cytoplasm. The pseudopodia form at different points along the cell, thus allowing the trophozoite to change directions. In their free-living state, trophozoites feed on bacteria. In tissues, they phagocytize red blood cells and white blood cells and destroy tissue.[7]

- Flagellate stage

This biflagellate form occurs when trophozites are exposed to a change in ionic concentration, such as placement in distilled water. The transformation of trophozoites to flagellate form occurs within a few minutes.[7]

Infection

In humans, N. fowleri can invade the central nervous system via the nose (specifically through the olfactory mucosa and cribriform plate of the nasal tissues). The penetration initially results in significant necrosis of and hemorrhaging in the olfactory bulbs. From there, the amoeba climbs along nerve fibers through the floor of the cranium via the cribriform plate and into the brain. The organism begins to consume cells of the brain piecemeal by means of a unique sucking apparatus extended from its cell surface.[9] It then becomes pathogenic, causing primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM or PAME). PAM is a syndrome affecting the central nervous system.[10] PAM usually occurs in healthy children or young adults with no prior history of immune compromise who have recently been exposed to bodies of fresh water.[11]

Amphotericin B is effective against N. fowleri in vitro, but the prognosis remains bleak for those who contract PAM, and survival remains less than 1%.[11] On the basis of the in vitro evidence alone, the CDC currently recommends treatment with amphotericin B for primary amoebic meningoencephalitis, but no evidence supports this treatment affecting outcome.[11] Treatment combining miconazole, sulfadiazine, and tetracycline has shown limited success only when administered early in the course of an infection.[12]

While miltefosine had therapeutic effects during an in vivo study in mice, chlorpromazine (Thorazine) showed to be the most effective substance - the authors concluded: "Chlorpromazine had the best therapeutic activity against N. fowleri in vitro and in vivo. Therefore, it may be a more useful therapeutic agent for the treatment of PAME than amphotericin B."[13]

Untimely diagnoses remain a very significant impediment to the successful treatment of infection, as most cases have only been discovered post mortem. Infection killed 121 people in the United States from 1937 through 2007, including six in 2007 (three in Florida, two in Texas, and one in Arizona).[11]

Symptoms

Onset symptoms of infection start about five days (range is from one to seven days) after exposure. The initial symptoms include, but are not limited to, changes in taste and smell, headache, fever, nausea, vomiting, and stiff neck. Secondary symptoms include confusion, hallucinations, lack of attention, ataxia, and seizures. After the start of symptoms, the disease progresses rapidly over three to seven days, with death occurring from seven to 14 days after exposure.[14]

Detection

N. fowleri can be grown in several kinds of liquid axenic media or on non-nutrient agar plates coated with bacteria. Escherichia coli can be used to overlay the non-nutrient agar plate and a drop of cerebrospinal fluid sediment is added to it. Plates are then incubated at 37°C and checked daily for clearing of the agar in thin tracks, which indicate the trophozoites have fed on the bacteria.[15] Detection in water is performed by centrifuging a water sample with E. coli added, then applying the pellet to a non-nutrient agar plate. After several days, the plate is microscopically inspected and Naegleria cysts are identified by their morphology. Final confirmation of the species' identity can be performed by various molecular or biochemical methods.[16] Confirmation of Naegleria presence can be done by a so-called flagellation test, where the organism is exposed to a hypotonic environment (distilled water). Naegleria, in contrast to other amoebae, differentiates within two hours into the flagellate state. Pathogenicity can be further confirmed by exposure to high temperature (42°C): Naegleria fowleri is able to grow at this temperature, but the nonpathogenic Naegleria gruberi is not.

Current research

Diagnostics

Current research is focused on development of real time PCR diagnostic methods. One method being developed involves monitoring the amplification process in real time with hybridization of fluorescent-labeled probes targeting the MpC15 sequence – which is unique to N. fowleri.[17] Another group has multiplexed three real-time PCR reactions as a diagnostic for N. fowleri, as well as Acanthamoeba spp. and Balamuthia mandrillaris.[18] This could prove to be an efficient diagnostic test.

Pathogenicity factors

As no effective treatment for P.A.M. has been found, the development of a therapeutic is an area of great research interest. Currently, much work is being done to determine what factor specific to N. fowleri makes it pathogenic and if these virulence factors can be targeted by drugs. One potential factor in motility of the "amoeba" is the protein coded by Nfa1. When the Nfa1 gene is expressed in nonpathogenic N. gruberi and the amoebae are concultivated with target tissue cells, the protein was found to be located on the food cup which is responsible for ingestion of cells during feeding.[19] Following up that research, Nfa1 gene expression knockdown experiments were performed using RNA interference. In this experiment, double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) targeting the Nfa1 sequence was introduced and subsequently expression levels of the gene product dramatically decreased.[20] This method could potentially be a technique applicable for knockdown of expression of pathogenicity factors in N. fowleri trophozoites.

Incidents and outbreaks

Czechoslovakia

- Between 1962 and 1965, 16 young people died of PAM in Ústí nad Labem as a consequence of bathing in an indoor swimming pool.[21]

New Zealand

- Between 1968 and 1978, eight fatal cases of PAM occurred after the victims had been swimming in geothermal water at locations between Taupo and Matamata, in the Waikato Region.[22]

Pakistan

- In Pakistan, on October 15, 2010, a 54-year-old male Ghulam Mustafa Khalid was admitted to a Karachi hospital, suffering from typical signs of meningitis.[23] It was quickly diagnosed as PAM and attempts to administer Amphotericin B, initially via IV then by intrathecal injection, had no effect. Cranial decompression of the patient likewise yielded no results, and the patient died on October 22, 2010.[24] He was in perfect health, had no history of swimming, however, he had a habit of deep nasal cleansing with tap water while doing wudu, which could possibly be the reason of this infection. [citation needed] Laboratory tests confirmed the presence of N. fowleri.

- From July to October 2012, 22 people died in the southern part of Pakistan within a week from Naegleria infection.[25] At least 13 cases has been reported in Karachi, Pakistan, who had no history of aquatic activities. Infection likely occurred through ablution with tap water. It may be attributed to rising temperatures, reduced levels of chlorine in potable water, or deteriorating water distribution systems.[26]

United Kingdom

- In 1979, a girl swimming in the restored Roman bath in the English city of Bath swallowed some of the source water, and died five days later from amoebic meningitis.[27] Tests showed that N. fowleri was in the water.[28] The pool was subsequently closed permanently[when?].

United States

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the protist killed 33 people between 1998 and 2007. In the 10 years from 2001 to 2010, 32 infections were reported in the U.S. Of those cases, 30 people were infected by contaminated recreational water and two people were infected by water from a geothermal (naturally hot) drinking water supply.[29]

- In October 2002, two Peoria, Arizona, five-year-olds died after being exposed to untreated water supplied by Rose Valley Water.[30]

- In August 2005, two Oklahoma boys, ages seven and nine, were killed by N. fowleri after swimming in the hot, stagnant water of lakes in the Tulsa area.[31]

- In 2007, six cases were reported in the U.S., all fatal.[11][32]

- August 2010, 7 year old Kyle Lewis died from the brain-eating amoeba Naegleria fowleri after swimming in fresh water in Texas. [33] www.KyleCares.org

Public health prevention strategies

Currently there are no widespread efforts for prevention because of the low prevalence of N. fowleri infections. However, because of the fatality of the ensuing meningoencephalitis, there are efforts in research and development of both diagnostics and treatment (see above). Additionally, a case can be made for increased awareness of N. fowleri and its infection for more accurate reporting.

Kyle Lewis Amoeba Awareness Foundation, created to spread awareness of this amoeba and the deadly infection it causes. www.KyleLewisAmoebaAwareness.org

Vaccine Research

There is no licensed vaccine in the US to protect against naegleria fowleri infection . Currently there are no widespread efforts for vaccine development because of the low prevalence of N. fowleri infections. However, because of the fatality of the ensuing meningoencephalitis, there are some efforts in vaccine research. Current research shows intranasal administration of Cry1Ac protoxin alone or in combination with amoebic lysates increases protection against Naegleria fowleri meningoencephalitis in mice. Studies are ongoing investigating whether the STAT6-induced Th2 immune response is essential for the resistance to N. fowleri infection, conferred by immunization with amoebic lysates plus Cry1Ac. protected STAT6+/+-immunized mice elicited a Th-2 type inclined immune response that produced predominantly humoral immunity, unprotected STAT6-/- mice exhibited a polarized Th1 type cellular response. These findings suggest that the STAT6-signalling pathway is critical for defence against N. fowleri infection. Immunization with Nfa1 protein on experimental murine PAM because of N. fowleri, BALB/c mice were intra-peritoneally or intra-nasally immunized with a recombinant Nfa1 protein..The mean survival time of mice immunized intra-peritoneally with rNfa1 protein was prolonged compared with controls, (25.0 and 15.5 days, respectively).

References in the media

N. fowleri was featured in the second season of House M.D. in the two-part episode "Euphoria (Part 1)" and "Euphoria (Part 2)". The amoeba was determined to be living in the water supply the deceased patient used to irrigate his marijuana garden.

In August 2009, N. fowleri was featured in the Animal Planet television series called Monsters Inside Me on the sixth episode entitled "Hijackers". The episode documented the story of how 11-year-old Will Sellars got infected with it by wakeboarding on a lake in Orlando, Florida, in July 2007. [34]

November 30, 2012, Monsters Inside Me features Kyle Lewis's story on Animal Planet [35]

See also

References

- ^ "The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Parasitic Diseases - Naegleria FAQs". Retrieved 2012-01-14.

- ^ "6 die from brain-eating amoeba after swimming". MSNBC. Associated Press. September 28, 2007.

- ^ "Naegleria fowleri". Stanford.edu. Retrieved 2012-09-04.

- ^ Fowler, M; Carter, RF (1965). "Acute pyogenic meningitis probably due to Acanthamoeba sp.: a preliminary report". British Medical Journal. 2 (5464): 740–2. PMC 1846173. PMID 5825411.

- ^ Butt, Cecil G. (1966). "Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis". New England Journal of Medicine. 274 (26): 1473–6. doi:10.1056/NEJM196606302742605. PMID 5939846.

- ^ Symmers, WC (1969). "Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis in Britain". British Medical Journal. 4 (5681): 449–54. doi:10.1136/bmj.4.5681.449. PMC 1630535. PMID 5354833.

- ^ a b c Marciano-Cabral, F (1988). "Biology of Naegleria spp". Microbiological reviews. 52 (1): 114–33. PMC 372708. PMID 3280964.

- ^ Chang, SL (1978). "Resistance of pathogenic Naegleria to some common physical and chemical agents". Applied and environmental microbiology. 35 (2): 368–75. PMC 242840. PMID 637538.

- ^ Marciano-Cabral, F; John, DT (1983). "Cytopathogenicity of Naegleria fowleri for rat neuroblastoma cell cultures: scanning electron microscopy study". Infection and immunity. 40 (3): 1214–7. PMC 348179. PMID 6852919.

- ^ Monsters Inside Me (2010-12-22). "Monsters Inside Me: The Brain-Eating Amoeba : Video : Animal Planet". Animal.discovery.com. Retrieved 2012-09-04.

- ^ a b c d e Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2008). "Primary amebic meningoencephalitis--Arizona, Florida, and Texas, 2007". MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 57 (21): 573–7. PMID 18509301.

- ^ Bauman, Robert W. (2009). "Microbial Diseases of the Nervous System and Eyes". Microbiology, With Diseases by Body System (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Pearson Education. p. 617.

- ^ Kim, J.-H.; Jung, S.-Y.; Lee, Y.-J.; Song, K.-J.; Kwon, D.; Kim, K.; Park, S.; Im, K.-I.; Shin, H.-J. (2008). "Effect of Therapeutic Chemical Agents In Vitro and on Experimental Meningoencephalitis Due to Naegleria fowleri". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 52 (11): 4010–6. doi:10.1128/AAC.00197-08. PMC 2573150. PMID 18765686.

- ^ http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/naegleria/faqs.html#symptoms

- ^ Donald C. Lehman; Mahon, Connie; Manuselis, George (2006). Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-2581-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)[page needed] - ^ Pougnard, C.; Catala, P.; Drocourt, J.-L.; Legastelois, S.; Pernin, P.; Pringuez, E.; Lebaron, P. (2002). "Rapid Detection and Enumeration of Naegleria fowleri in Surface Waters by Solid-Phase Cytometry". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 68 (6): 3102–7. doi:10.1128/AEM.68.6.3102-3107.2002. PMC 123984. PMID 12039772.

- ^ Maďarová, Lucia; Trnková, Katarína; Feiková, Soňa; Klement, Cyril; Obernauerová, Margita (2010). "A real-time PCR diagnostic method for detection of Naegleria fowleri". Experimental Parasitology. 126 (1): 37–41. doi:10.1016/j.exppara.2009.11.001. PMID 19919836.

- ^ Qvarnstrom, Y.; Visvesvara, G. S.; Sriram, R.; Da Silva, A. J. (2006). "Multiplex Real-Time PCR Assay for Simultaneous Detection of Acanthamoeba spp., Balamuthia mandrillaris, and Naegleria fowleri". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 44 (10): 3589–95. doi:10.1128/JCM.00875-06. PMC 1594764. PMID 17021087.

- ^ Song, K; Jeong, S; Park, S; Kim, K; Kwon, M; Im, K; Pak, J; Shin, H (2006). "Naegleria fowleri: Functional expression of the Nfa1 protein in transfected Naegleria gruberi by promoter modification". Experimental Parasitology. 112 (2): 115–20. doi:10.1016/j.exppara.2005.10.004. PMID 16321386.

- ^ Jung, S; Kim, J; Lee, Y; Song, K; Kim, K; Park, S; Im, K; Shin, H (2008). "Naegleria fowleri: nfa1 gene knock-down by double-stranded RNAs". Experimental Parasitology. 118 (2): 208–13. doi:10.1016/j.exppara.2007.08.008. PMID 17904122.

- ^ Ccaronerva, L.; Novak, K. (1968). "Amoebic Meningoencephalitis: Sixteen Fatalities". Science. 160 (3823): 92–92. doi:10.1126/science.160.3823.92. PMID 5642317.

- ^ Cursons, R; Sleigh, J; Hood, D; Pullon, D (2003). "A case of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis: North Island, New Zealand". The New Zealand medical journal. 116 (1187): U712. PMID 14752540.

- ^ "Brain Eating Amoeba invades Pakistan - Teeth Maestro". Retrieved 2010-10-27.

- ^ "Dawn News e-paper - Obituary of Ghulam Mustafa Khalid". Retrieved 2010-10-23.

- ^ "At least 10 dies in Karachi due to Naegleria". Retrieved 2012-7-19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ cdc.gov - Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis Caused by Naegleria fowleri, Karachi, Pakistan, 2011-07-08

- ^ "The City of Bath, Somerset, UK". H2G2. Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- ^ Kilvington, Simon (1995). "Identification and epidemiological typing of Naegleria fowleri with DNA probes" (PDF). Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 61 (6): 2071–2078. PMC 167479. PMID 7793928. Retrieved 2007-10-31.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Naegleria - Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. July 5, 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-17.

- ^ "Suicide Deaths" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-08-17.

- ^ "Parasitic Infection Kills Two Tulsa Swimmers". Retrieved 2005-08-06.

- ^ "Rare but deadly amoeba infection hard to predict". Retrieved 2012-10-10.

- ^ "Family Warns Swimmers About Brain-Eating Amoeba".

- ^ "'The Brain-Eating Amoeba, aka Naegleria fowleri'". 'Discovery Communications, LLC'. Retrieved 2012-04-25.

- ^ "'Season 3 Episode 9'".