Perpetual motion: Difference between revisions

Cometstyles (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 165.139.190.15 (talk) to last version by Kmarinas86 |

→Ubiquitous energy from atomic and chemical bonds: nuclear and other power sources are not so free. large amounts of energy must go into construction, operation, and later dismantling |

||

| Line 112: | Line 112: | ||

All working energy devices require either a heat reservoir (such as [[solar radiation]]) or a process of utilizing dense stores of energy (such as [[nuclear energy]] or [[chemical energy]]). [[Heat pumps]] are capable of transporting this waste heat in excess of the heat used to run them (cf. [[Coefficient of performance]]>1), but are not perpetual motion machines because the transferred heat is part of the input. |

All working energy devices require either a heat reservoir (such as [[solar radiation]]) or a process of utilizing dense stores of energy (such as [[nuclear energy]] or [[chemical energy]]). [[Heat pumps]] are capable of transporting this waste heat in excess of the heat used to run them (cf. [[Coefficient of performance]]>1), but are not perpetual motion machines because the transferred heat is part of the input. |

||

Conventional sources of energy such as [[petroleum]] and [[natural gas]] or radioactive materials such as [[uranium]] rely on a small fraction of the inherent and ubiquitous energy of atoms and molecules, although the energy of atoms and molecules are not characterized by |

Conventional sources of energy such as [[petroleum]] and [[natural gas]] or radioactive materials such as [[uranium]] rely on a small fraction of the inherent and ubiquitous energy of atoms and molecules, although the energy of atoms and molecules are not characterized by an internal temperature. Electrical power plants can only only be profitable by extracting the nuclear and chemical energies in excess of the energy needed to: |

||

* locate and mine the construction materials, process them into usable form (concrete, steel), and build the plant |

|||

* locate, mine/extract, transport, purify, concentrate, and react the fuel materials |

|||

* operate the plant in a safe and stable manner |

|||

* repurify uranium waste back into usable fuel |

|||

* decomission and dismantle the retired power plants |

|||

Scientists are currently spending many research hours in attempt of getting more power out of [[nuclear fusion]] than what it takes to run the power plant. If solved, nuclear fusion would supply the world with an abundant source of electricity. The entire [[energy industry]] relies on a system where thermal output exceeds the thermal input. When determining the present thermal output that exceeds present thermal input, one only considers the time during which the energy of the fuel is consumed, and not the time during which the energy was stored in that fuel. |

|||

==Perpetual motion in popular culture== |

==Perpetual motion in popular culture== |

||

Revision as of 03:56, 2 April 2008

The term perpetual motion, taken literally, refers to movement that goes on forever. However, perpetual motion usually refers to a device or system that delivers more energy than was put into it. Such a device or system would be in violation of the law of conservation of energy, which states that energy can never be created or destroyed, and is therefore deemed impossible by the laws of physics. The most conventional type of perpetual motion machine is a mechanical system which (supposedly) sustains motion while inevitably losing energy to friction, and air resistance.

Basic principles

Perpetual motion machines violate the first law of thermodynamics, the second law of thermodynamics, or both. The first law of thermodynamics is essentially a statement of conservation of energy. The second law has several statements, the most intuitive of which is that heat flows spontaneously from hotter to colder places; the most well known is that entropy tends to increase, or at the least stays the same; another statement is that no heat engine (an engine which produces work while moving heat between two places) can be more efficient than a Carnot heat engine. As a special case of this, any machine operating in a closed cycle cannot only transform thermal energy to work in a region of constant temperature.

Machines which are claimed not to violate either of the two laws of thermodynamics but rather are claimed to generate energy from unconventional sources are sometimes referred to as perpetual motion machines, although they are generally reported as not meeting the standard criteria for the name. By way of example, it is quite possible to design a clock or other low-power machine to run on the differences in barometric pressure or temperature between night and day.[1] Such a machine has a source of energy, albeit one from which it is quite impractical to produce power in quantity.

Classification

It is customary to classify perpetual motion machines as follows:

- A perpetual motion machine of the first kind produces strictly more energy than it uses, giving the user unlimited energy. It thus violates the law of conservation of energy. Over-unity devices, that is, devices with a thermodynamic efficiency greater than 1.0 (unity, or 100%), are perpetual motion machines of this kind.

- A perpetual motion machine of the second kind is a machine which spontaneously converts thermal energy into mechanical work. This need not violate the law of conservation of energy, since the thermal energy may be equivalent to the work done; however it does violate the more subtle second law of thermodynamics (see also entropy). Note that such a machine is different from real heat engines (such as car engines), which always involve a transfer of heat from a hotter reservoir to a colder one, the latter being warmed up in the process. The signature of a perpetual motion machine of the second kind is that there is only one single heat reservoir involved, which is being spontaneously cooled without involving a transfer of heat to a cooler reservoir. This conversion of heat into useful work, without any side effect, is impossible by the second law of thermodynamics.

In an otherwise completely empty Newtonian universe, a single particle could travel forever at a constant velocity with no violation of the laws of physics – though of course no energy could be extracted from it without slowing it down. For example, in an isolated system consisting of two objects orbiting each other gravitationally, the two objects will remain orbiting forever, as long as they are not disturbed. However any attempt to extract useful work from this system would lead to a loss of energy. This would result in the objects slowing down and getting closer to each other, until at some point the objects would collapse together and no more energy would remain to extract.

Use of the term "impossible" and perpetual motion

Scientists and engineers accept the possibility that the current understanding of the laws of physics may be incomplete or incorrect; a perpetual motion device may not be impossible, but overwhelming evidence would be required to justify rewriting the laws of physics.

The conservation laws are particularly robust. Noether's theorem states that any conservation law can be derived from a corresponding continuous symmetry, and the theorem can be proven. In other words, as long as the laws of physics (not simply the current understanding of them, but the actual laws, which may still be undiscovered) and the various physical constants remain invariant over time — as long as the laws of the universe are fixed — then the conservation laws must be true, in the sense that they follow from the presupposition using mathematical logic. To put it the other way around: if perpetual motion or "overunity" machines were possible, then most of what we believe to be true about physics, mathematics, or both would have to be false.

The principles of thermodynamics are so well established, both theoretically and experimentally, that proposals for perpetual motion machines are universally met with disbelief on the part of physicists. Any proposed perpetual motion design offers a potentially instructive challenge to physicists: one is almost completely certain that it can't work, so one must explain how it fails to work. The difficulty (and the value) of such an exercise depends on the subtlety of the proposal; the best ones tend to arise from physicists' own thought experiments and often shed light into unique aspects of physics.

The law that entropy always increases, holds, I think, the supreme position among the laws of Nature. If someone points out to you that your pet theory of the universe is in disagreement with Maxwell's equations — then so much the worse for Maxwell's equations. If it is found to be contradicted by observation — well, these experimentalists do bungle things sometimes. But if your theory is found to be against the second law of thermodynamics I can give you no hope; there is nothing for it but to collapse in deepest humiliation. — Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington, The Nature of the Physical World (1927)

Thought experiments

Serious work in theoretical physics often involves thought experiments that test the boundaries of understanding of physical laws. Some such thought experiments involve apparent perpetual motion machines, and insight may be had from understanding why they either don't work or don't violate the laws of physics.

- Maxwell's demon: A thought experiment which led to physicists' considering the interaction between entropy and information.

- Feynman's "Brownian ratchet": A "perpetual motion" machine which extracts work from thermal fluctuations and appears to run forever but really only runs as long as the environment is warmer than the ratchet.

- Self-perpetuating cosmic inflation: Andrei Linde has proposed that during the theoretical period of cosmic inflation in the early universe, quantum fluctuations in energy could be magnified by the very inflationary process, preventing the global cooling trend from ever being fully consummated. This would violate both the first and second laws of thermodynamics; indeed, it may constitute the origin of a low-entropy past that gets the second law going in the first place. However, a machine to harness this principle would have several serious flaws. It would need to use unimaginable amounts of energy (on at least a Planck scale); it might have cataclysmic consequences to the area around it for an unknown distance (there is not a prior natural limit to the scale of the damage); and at least the majority and possibly all the energy it generated would be in a newly-created universe which might be inaccessibly far away along a wormhole.

Techniques

One day man will connect his apparatus to the very wheelwork of the universe [...] and the very forces that motivate the planets in their orbits and cause them to rotate will rotate his own machinary.

Some common ideas recur repeatedly in perpetual motion machine designs.

The seemingly mysterious ability of magnets to influence motion at a distance without any apparent energy source has long appealed to inventors. However, a constant magnetic field can do no work because the force it exerts on a charged particle is always at right angles to its motion; a changing field can do work, but requires energy to sustain. A "fixed" magnet can do work, but energy is dissipated in the process, typically weakening the magnet's strength over time. Thus, when a magnet does work by lifting an iron weight, potential energy is converted to kinetic energy. Once the iron hits the magnet its kinetic energy is converted to heat and sound. In order to release further energy, the iron must be moved away from the magnet. This converts the energy of your arm to potential energy again. Since the energy of parting the magnet and iron is identical to the energy released as the magnet and iron come together, no net energy can be gained by changing the iron – magnet distance.

Gravity also acts at a distance, without an apparent energy source. But to get energy out of a gravitational field (for instance, by dropping a heavy object, producing kinetic energy as it falls) you have to put energy in (for instance, by lifting the object up), and some energy is always dissipated in the process. A typical application of gravity in a perpetual motion machine is Bhaskara's wheel in the 12th century, whose key idea is itself a recurring theme, often called the overbalanced wheel: Moving weights are attached to a wheel in such a way that they fall to a position further from the wheel's center for one half of the wheel's rotation, and closer to the center for the other half. Since weights further from the center apply a greater torque, the result is (or would be, if such a device worked) that the wheel rotates forever. The moving weights may be hammers on pivoted arms, or rolling balls, or mercury in tubes; the principle is the same.

Gravity and magnetism are an attractive combination indeed, and a frequently rediscovered design has a ball pulled up by a magnetic field and then rolling down under the influence of gravity, in a cycle. (At the highest point, the ball is supposed to have acquired enough speed to escape the magnet's influence.)

Yet another theoretical machine involves a frictionless environment for motion. This involves the use of diamagnetic or electromagnet levitation to float an object. This is done in a vacuum to eliminate air friction and friction from an axle. The levitated object is then free to rotate around its center of gravity without interference. However, this machine has no practical purpose because the rotated object cannot do any work as work requires the levitated object to cause motion in other objects, bringing friction into the problem.

To extract work from heat, thus producing a perpetual motion machine of the second kind, the most common approach (dating back at least to Maxwell's demon) is unidirectionality. Only molecules moving fast enough and in the right direction are allowed through the demon's trap door. In a Brownian ratchet, forces tending to turn the ratchet one way are able to do so while forces in the other direction aren't. A diode in a heat bath allows through currents in one direction and not the other. These schemes typically fail in two ways: either maintaining the unidirectionality costs energy (Maxwell's demon needs light to look at all those particles and see what they're doing), or the unidirectionality is an illusion and occasional big violations make up for the frequent small non-violations (the Brownian ratchet will be subject to internal Brownian forces and therefore will sometimes turn the wrong way).

Invention history

Hero of Alexandria created what might be considered the first near-perpetual motion machine. However, it is not recorded that he claimed his fountain ran by perpetual motion. The recorded history of referenced perpetual motion machines date back to the 12th century. Proponents of perpetual motion machines use a number of other terms to describe their inventions, including "free energy" and "over unity" machines. The earliest references to perpetual motion machines date back to 1150, by an Indian mathematician-astronomer, Bhāskara II. He described a wheel that he claimed would run forever. Villard de Honnecourt in 1235 described, in a thirty-three page manuscript, a perpetual motion machine of the second kind. Robert Boyle's self-flowing flask appears to fill itself through siphon action. This is not possible in reality; a siphon requires its "output" to be lower than the "input".

In 1775 Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris issued the statement that Academy "will no longer accept or deal with proposals concerning perpetual motion". Johann Bessler (also known as Orffyreus) created a series of claimed perpetual motion machines in the 18th Century. In the 19th century, the invention of perpetual motion machines became an obsession for many scientists. Many machines were designed based on electricity, but none of them lived up to their promises. Another early prospector in this field was John Gamgee. Gamgee developed the Zeromotor, a perpetual motion machine of the second kind.

Devising these machines is a favourite pastime of many eccentrics, who often come up with elaborate machines in the style of Rube Goldberg or Heath Robinson. These designs may appear to work on paper at first glance. Usually, though, various flaws or obfuscated external power sources have been incorporated into the machine. Such activity has made them useless in the practice of "invention".

Patents

Devising such inoperable machines has become common enough that the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has made an official policy of refusing to grant patents for perpetual motion machines without a working model. One reason for this concern, according to various skeptics, is that a few "inventors" have used official patents to convince gullible potential investors that their machine is "approved" by the Patent Office.[citation needed] The USPTO Manual of Patent Examining Practice states:

- With the exception of cases involving perpetual motion, a model is not ordinarily required by the Office to demonstrate the operability of a device. If operability of a device is questioned, the applicant must establish it to the satisfaction of the examiner, but he or she may choose his or her own way of so doing.[2]

And, further, that:

- A rejection [of a patent application] on the ground of lack of utility includes the more specific grounds of inoperativeness, involving perpetual motion. A rejection under 35 U.S.C. 101 for lack of utility should not be based on grounds that the invention is frivolous, fraudulent or against public policy.[3]

The USPTO has granted a few patents for motors that are claimed to run without net energy input. These patents were issued because, skeptics claim, it was not obvious from the patent that a perpetual motion machine was being claimed.[citation needed] Some of these are:

| Howard R. Johnson, U.S. Patent 4,151,431 |

|---|

|

- Johnson, Howard R., U.S. patent 4,151,431 "Permanent magnet motor", April 24, 1979

- Baker, Daniel, U.S. patent 4,074,153 "Magnetic propulsion device", February 14, 1978

- Hartman; Emil T., U.S. patent 4,215,330 "Permanent magnet propulsion system", December 20, 1977 (this device is related to the Simple Magnetic Overunity Toy (SMOT)),

- Flynn; Charles J., U.S. patent 6,246,561 "Methods for controlling the path of magnetic flux from a permanent magnet and devices incorporating the same", July 31, 1998

- Patrick, et al., U.S. patent 6,362,718 "Motionless electromagnetic generator" , March 26, 2002

- Green, Willie A., U.S. patent 6,526,925 "Piston Driven Rotary Engine", March 4, 2003 "Fluid driven device utilizing a leveraged system with minimal displacement"

- Goldenblum, Halm, U.S. patent 6,962,052 "Energy generation mechanism, device and system", November 8, 2005 "A chamber with a partition which lets gas molecules flow one way and not the other. The pressure which builds up on one side of the partition is used to drive a generator."

- Flynn, Joe, U.S. patent 6,246,561 "Methods for controlling the path of magnetic flux from a permanent magnet and devices incorporating the same", June 12, 2001

- Gates; Glenn A., U.S. patent 6,523,646 "Spring driven apparatus", February 23, 2003 "Energy is stored in the springs and power is generated by way of the various forces which cause the springs to wind and unwind."

In 1979, Joseph Newman filed a US Patent application for his "energy machine" which unambiguously claimed over-unity operation, where power output exceeded power input; the source of energy was claimed to be the atoms of the machine's copper conductor.[4] The Patent Office rejected the application after the National Bureau of Standards measured the electrical input to be greater than the electrical output. Newman challenged the decision in court and lost.[5]

Other patent offices around the world have similar practices, such as the United Kingdom Patent Office. Section 4.05 of the UKPO Manual of Patent Practice states:

- Processes or articles alleged to operate in a manner which is clearly contrary to well-established physical laws, such as perpetual motion machines, are regarded as not having industrial application.[6]

Examples of decisions by the UK Patent Office to refuse patent applications for perpetual motion machines include:

- Decision BL O/044/06, John Frederick Willmott's application no. 0502841[7]

- Decision BL O/150/06, Ezra Shimshi's application no. 0417271[8]

Apparent perpetual motion machines

Even though they fully respect the laws of thermodynamics, there are a few conceptual or real devices that appear to be in "perpetual motion", while a closer analysis reveals them to actually "consume" some sort of natural resource or latent energy like the phase changes of water or other fluids, solar energy and natural, small temperature gradients. In general, extracting useful work out of similar devices is very hard or almost impossible, as those devices usually work with low-grade heat and with very low efficiency.

So, these devices can mostly be classified as low-power, low-efficiency energy converters (not free energy producers) which are able to use low grade energy sources, but which would be impractical or impossible to use at a large scale for mass energy production, as efficiency would be extremely low, as well as any power output – if any.

Some examples of real such devices include:

- The drinking bird toy (the energy comes from small ambient temperature gradients and evaporation, and harnessing the small power output would likely disrupt the working cycle).

- A capillarity based water pump: in this case, energy would again come from small ambient temperature gradients and vapour pressure differences, although it would be far too easy for the pump to stop functioning.

- A Crookes radiometer, a partial vacuum glass container with a lightweight propeller moved by (light-induced) temperature gradients.

- Any device picking minimal amounts of energy from the electromagnetic radiation around it. Some modern smart labels (RFID chips) actually work based on that principle, using the same electromagnetic field used for "reading" them as their powersource.

- In the Atmos clock the vapor pressure of ethyl chloride changes with temperature and winds up the clock spring.

Some examples of imaginary such devices:

- A ship or a large power plant using the temperature gradient and heat transfer between a large surface exposed to the sun (or another heat source) and a colder one (e.g., the sea or the ground). This would actually be a low-efficiency solar generator, far less efficient than conventional solar cells.

- Any other similar device using a combination of small temperature gradients, heat pipes, evaporation, phase transitions, solar energy, electromagnetic radiation etc.

In all of these cases the "free" energy would, in any case, come from "lesser" forms of energy already present in the environment in small quantities, and the net power outputs would be extremely small to build a large-scale generator. While it certainly is possible to convert some of the ambient's low-grade heat into useful work, that would not be, by definition, "perpetual motion", and the efficiencies are so low that such devices can only be used as toys or novelty items.

Ubiquitous energy from atomic and chemical bonds

All working energy devices require either a heat reservoir (such as solar radiation) or a process of utilizing dense stores of energy (such as nuclear energy or chemical energy). Heat pumps are capable of transporting this waste heat in excess of the heat used to run them (cf. Coefficient of performance>1), but are not perpetual motion machines because the transferred heat is part of the input.

Conventional sources of energy such as petroleum and natural gas or radioactive materials such as uranium rely on a small fraction of the inherent and ubiquitous energy of atoms and molecules, although the energy of atoms and molecules are not characterized by an internal temperature. Electrical power plants can only only be profitable by extracting the nuclear and chemical energies in excess of the energy needed to:

- locate and mine the construction materials, process them into usable form (concrete, steel), and build the plant

- locate, mine/extract, transport, purify, concentrate, and react the fuel materials

- operate the plant in a safe and stable manner

- repurify uranium waste back into usable fuel

- decomission and dismantle the retired power plants

Scientists are currently spending many research hours in attempt of getting more power out of nuclear fusion than what it takes to run the power plant. If solved, nuclear fusion would supply the world with an abundant source of electricity. The entire energy industry relies on a system where thermal output exceeds the thermal input. When determining the present thermal output that exceeds present thermal input, one only considers the time during which the energy of the fuel is consumed, and not the time during which the energy was stored in that fuel.

Perpetual motion in popular culture

This article contains a list of miscellaneous information. (December 2007) |

- In Mark Helprin's A City In Winter, a clock tower's machinery, constructed of jewels and precious gems, is stated to be a perpetual motion machine, given by God.

- The Selenite power station in the 1964 adaptation of H.G. Wells' First Men in the Moon is purported to be "Perpetual Motion – if it weren't impossible…".

- In "The PTA Disbands" episode of The Simpsons, Lisa builds a perpetual motion machine when there was no school due to a teachers' strike; after seeing the machine, her father Homer says: "This perpetual motion machine Lisa made is a joke, it just keeps going faster and faster," and afterwards yells at her saying "Lisa, get in here…In this house, we obey the laws of thermodynamics!"

- In the Playstation 2 video games Xenosaga I & II, and in the Playstation 1 video game Xenogears, the device, called the Zohar, is a form of a perpetual motion machine. It is briefly described as a Pseudo-Perpetual Infinite Energy Engine.

- Thomas Pynchon's The Crying of Lot 49 includes the description of a suggested perpetual motion machine, along with an explanation as to why it doesn't work.

- In the computer game The Sims, a complex (and very expensive) perpetual motion machine can be bought as a household decoration. No devices are available, however, to harness it to do any work.

- In the computer role-playing game Ultima VI: The False Prophet, a perpetual motion machine is on display in the museum in Britain.

- One episode of the Nickelodeon program Invader Zim showcased a Perpetual Energy Generator (or as its creator likes to call it, PEG) that is never activated due to the impatience of a member of the crowd present at the activation ceremony.

- In episode 16, The Great Sandcastle Race, of the Nickelodeon animated series, Rocket Power, one group makes a perpetual motion machine instead of a sandcastle.

- In Disney's Recess, one episode shows Gretchen Grundler creating a perpetual motion machine for her science project. Upon her demonstration to the class, a team of government agents photograph the blackboard equations, consfiscate the model, and remove evidence of its existence.

- A perpetual motion machine was featured in episode 10 of the anime series Cowboy Bebop, "Ganymede Elegy". It is repeatedly seen in Alisa's bar, La Fin.

- In 2006, the DCI corps, Santa Clara Vanguard, performed a show entitled "Moto Perpetuo," based on the theme of constant movement in music and drill.

- In the fighting game Tekken, character Bryan Fury has a perpetual energy generator built within him by Doctor Boskonovitch which grants him unlimited power.

- In the Creedence Clearwater Revival song, "Up Around the Bend", the third verse begins, "You can ponder perpetual motion."

- In Terry Pratchett's Thud!, the Dwarves have several "devices" and the ones called "axles" appear to be some kind of perpetual motion device, turning with no apparent way to stop them.

- In the Kurt Vonnegut novel Hocus Pocus, the main character, an instructor at a school for learning-disabled youths, gets his class to attempt the creation of perpetual motion machines. After they experience sundry failures, he places the devices on display for the public, under a banner that caustically reads: "The Complicated Futility of Ignorance."

- In Angels and Demons by Dan Brown, one plot hinge is that a Catholic scientist succeeds in verifying Genesis by creating quantities of matter and antimatter out of nothing, for an energy input far less than the amount of mass created — so that annihilation of the antimatter would yield a vast amount of energy. This has been debunked by CERN[9] as constituting a perpertual-motion device.

- The Last Question, a short story by the late Isaac Asimov, is concerned with the reversal of entropy — in effect, perpertual motion.

- The Billiard Ball, a short story by the late Isaac Asimov, contains a device which neutralises the mass of objects within its field, so that they are thus compelled to instantly attain the speed of light − part of the energy subsequently extracted from them is fed back to maintain the field.

- In the science fiction novel Pushing Ice by Alastair Reynolds spinning wheels are constructed and placed over areas of the moon where the local gravity is greater than that of the surrounding area. With the wheels half over the area and half not. This causes the wheels to spin perpetually providing energy

- Matthew Reilly's novel Six Sacred Stones features several diamond pillars created by a pre-human civilization. One of these eventually 'reveals' the secret of perpetual motion (as discovered by this civilization), or limitless energy, but it is never explained in the book.

- Perpetual Motion Machine is the name of a jazz/funk/blues quintet from Long Island, New York, USA.

- In the Gundam 00 anime,a GN Drive is a Semi-Perpetual motion generator that installed in the Gundam mobile suits that generates special particles called GN Particles.It can run for an unlimited amount of time and creates an inexhaustible amount of energy for the use of the Gundam.It is mentioned that it can only be constructed in Jupiter's atmosphere using topological defects and the time needed is possibly decades leaving mass production out of the question.It differs from a GN Drive Tau which can run for a limited amount of time before needing to be recharged but can be mass produced more easily.

Examples

- Water fuel cell A car that purportedly runs by converting water into hydrogen and harnessing the energy of hydrogen combustion (which, in turn, emits water vapor that can be refueled to the car)

- Motionless Electromagnetic Generator, a device that supposedly taps vacuum energy.

- Steorn Ltd., a company that claims to have built a motor using only permanent magnets.

- Perepiteia, a device that claims to utilize back EMF

Gallery

This is a gallery of some of the perpetual motion machine plans.

-

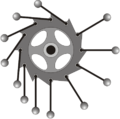

The "Overbalanced Wheel". It was thought that the metal balls on the right side would turn the wheel because of gravity, but since the left side had more balls than the right side, the weight was balanced and the perpetual movement could not be achieved.

-

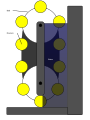

The "Float Belt". The yellow blocks indicate floaters. It was thought that the floaters would rise through the liquid and turn the belt. However pushing the floaters into the water at the bottom would require more energy than the floating could generate.

-

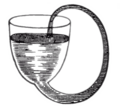

The "Capillary Bowl". It was thought that the capillary action would keep the water flowing in the tube, but since the mass of the water is bigger than the power that the capillary action could generate, the movement will not be perpetual.

-

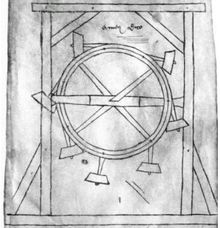

The "Sand Tube Magical Wheel". The black parts indicate sand. It was planned to be a replacement after the original Magic wheel failed. It works with the same theory of the original wheel, and ends up the same.

See also

- Free energy suppression, the conspiracy theory that free energy technology is suppressed by special interests.

- Unlimited energy

- Magic compression algorithm, a computer science counterpart of perpetual motion

Notes

- ^ Cox's timepiece

- ^ 608.03 Models, Exhibits, Specimens [R-3 – 600 Parts, Form, and Content of Application]

- ^ 706.03(a) Rejections Under 35 U.S.C. 101 [R-3 – 700 Examination of Applications II. UTILITY]

- ^ "A Patent Pursuit: Joe Newman's 'Energy Machine', Science News, June 1, 1985

- ^ "NBS Report Short Circuits Energy Machine", Science News, July 5, 1986

- ^ http://www.patent.gov.uk/practice-sec-004.pdf

- ^ Patents Ex parte decision (O/044/06)

- ^ http://www.patent.gov.uk/patent/p-decisionmaking/p-challenge/p-challenge-decision-results/o15006.pdf

- ^ CERN - Spotlight: Angels and Demons

References

- Veljko Milković and Nebojša Simin (2001). Perpetuum mobile. Novi Sad (Serbia), Vrelo.

- Perpetuum Mobile

- Perpetuum Mobile Video.

- Perpetuum Mobile Site.

External links

Historic

- The Museum of Unworkable Devices

- Donald Simanek's History of Perpetual Motion Machines

- Richard Clegg, "Perpetual Motion Page", richardclegg.org.

- A selection of Bhaskara-like devices

Research

- Kevin Kilty's perpetual motion page

- (Dead Link) Vlatko Vedral's Lengthy discussion of Maxwell's Demon (PDF)

In Popular Culture

- An Israeli juggling act named "Perpetuum Mobile".

- "Perpetual Motion Machine" - Jazz/Funk/Blues quintet from Long Island, NY