Swains Island

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2014) |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 11°03′20″S 171°04′40″W / 11.05556°S 171.07778°W |

| Archipelago | Tokelau |

| Administration | |

United States | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 17[1] |

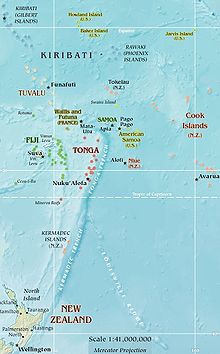

Swains Island (/ˈsweɪnz/; Samoan: Olosega; Tokelauan: Olohega) is an atoll in the Tokelau chain. The island is subject to an ongoing territorial dispute between Tokelau, of which the island is culturally part, and the United States of America, which administers it as part of American Samoa.[2][3] Owned by the Jennings family and used as a copra plantation, Swains Island has a population of 17 Tokelauans, who harvest the island's coconuts. The land area is 1.5 km2.

Other names

Swains Island has also been known at various times as Olosenga Island, Olohega Island, Quiros Island, Gente Hermosa Island, and Jennings Island.

Geography and demographics

Swains Island has a total area of 460.9 acres (186.5 ha), of which 373 acres (150.8 ha) is land. The central lagoon accounts for 88 acres (35.8 ha). There is a small islet of 914 square yards (764 m2) in the eastern part of the lagoon.

The atoll is somewhat unusual, featuring an unbroken circle of land enclosing a formerly freshwater lagoon cut off from the sea. Recent U.S. Coast Guard visitors to Swains described its lagoon as "brackish" and a source for the plentiful numbers of mosquitoes which plague the island.[4] In April 2007, a member of an amateur radio expedition confirmed that the lagoon water was fit only for bathing and washing, and that fresh water seemed to be in rather short supply on the island at the time.[5] According to a United States Department of the Interior description of Swains Island, drinking water on Swains is derived entirely from rainfall collected in two large mahogany tanks near the island's copra shed.[6]

As of 2005[update], the population of Swains Island was 37, all located in the village of Taulaga on the island's west side. According to the Interior Department report, Taulaga prior to 2005 consisted of a grassy malae (an open space similar to an American "village green"), twenty or so fale (Tokelauan-style houses), and a large red copra shed that doubled as the town hall and water-collection system.[citation needed]

A communications building, school and church completed Taulaga's buildings. Only the church remained standing after Cyclone Percy in 2005, though other structures have since been rebuilt.[7] The 2010 United States Census reported only 17 inhabitants on the island.[8][9]

The village of Etena in the southeast, once home to the expansive "residency" of Swains' unique dynasty of "proprietors", is now abandoned. This "residency", as it was called, consisted of a rustic four-bedroom house built in the 1800s to accommodate the Jennings family, owners of the island. A visitor to Swains Island in the 1920s described the mansion as being "dilapidated, though stately", noting that parts of it were not being used even at that time.[10] A road, the Old Belt Road, once ran around the island rim, but it seems to have been reduced in recent years to an overgrown jungle trail.[11]

The Samoan government official Rep. Sua Alex Jennings has recently sought to diversify the economy by growing breadfruit for export as breadfruit flour for sale in Samoa, Hawaii and the United States.[12][13]

Swains Islanders mainly speak Tokelauan, making them a tiny linguistic minority in American Samoa where the principal language is Samoan.

History and etymology

One major misconception that still sticks to the Western discovery of modern Swains Island is that it was discovered on March 2, 1606, by Pedro Fernandes de Queirós, a famous Portuguese navigator who sailed for Spain. The island that was seen by him on that day, also reckoned by him to lie in 10° 36' S. 171° W., was almost certainly modern Rakahanga, which is in 10° 02' S. 161° 05' W.[14][15] The name assigned to his discovery was Isla de la Gente Hermosa, which roughly translates to the "island of beautiful people" in Spanish.

When Captain William L. Hudson of the USS Peacock came in sight of the modern Swains Island on 1 February 1841, but finding the island not to be in the position as reported by Queirós, Hudson resolved to call it "Swain's Island":

"from having its position very nearly pointed out to me by Capt. Swain of Nantucket who stated to me at Tahiti that he had seen it in passing - and in consequence of its being a considerable distance in latitude from, and not agreeing in size or character with the island described by Queros - in addition to this in view of it being peopled with a beautiful race - it is uninhabited and perhaps we are the first that have ever set foot upon it - thus much for its name." [16]

Two sources claim that Hudson was informed about the existence of Swains Island by William Chown Swain of the whaler George Champlain of Newport, Rhode Island, and that this captain handed him its co-ordinates, 11 degrees south and 170 degrees west.[17][18] However, recent speculation is that the Swain who had told Hudson about this island was not William Chown Swain but was instead Obed Swain of the whaler Jefferson of Nantucket whom, unlike the former captain, actually was at Tahiti when the United States Exploring Expedition was there with the USS Peacock, Capt. Hudson.[19]

The Jennings family

Fakaofoans returned to the island soon after Hudson's visit, and were joined by three Frenchmen, who then left to sell the coconut oil they had accumulated.[6] In 1856, an American, Eli Hutchinson Jennings (14 November 1814 – 4 December 1878), joined a community on Swains with his Samoan wife, Malia. Jennings claimed to have received title to the atoll from a British Captain Turnbull, who claimed ownership of the island by discovery and named it after himself. According to one account, the sale price for Swains was fifteen shillings per acre (37 shillings per hectare), and a bottle of gin.[7] One of the Frenchmen later returned, but did not care to share the island with Jennings and left.[20]

On 13 October 1856, Swains became a semi-independent proprietary settlement of the Jennings family (although under the U.S. flag), a status it would retain for approximately seventy years. It was also claimed for the U.S. by the United States Guano Company in 1860, under the Guano Islands Act.[20]

Jennings established a coconut plantation, which flourished under his son, Eli, Junior. Eli Jennings, Senior was also instrumental in helping Peruvian "blackbird" slave ships to depopulate the other three Tokelau atolls—see H.E. Maude's Slavers in Paradise (A.N.U., Canberra, 1981).

American sovereignty confirmed

In 1907, the Resident Commissioner of the British Gilbert and Ellice Islands (then a British protectorate; since 1979 the sovereign nations of Kiribati and Tuvalu) claimed that Swains belonged to the United Kingdom, demanding payment of a tax of US$85. Jennings paid, but he brought the matter before the U.S. State Department, and his money was ultimately refunded. The British government furthermore conceded that Swains was an American possession.

The ownership of the island came into question after Eli Jr.'s death in 1920 and that of his wife in 1921. The United States decided to give the right of administration jointly to Eli's daughter Ann and son Alexander, while making it officially part of American Samoa by annexation on 4 March 1925. Alexander Jennings, the son of Eli Jennings, Jr., became managing owner of the island. The population at this time was around 100. During the Pacific War, the island had a population of 125, and had a naval radio station.[21]

In 1953, labor troubles arose on Swains when Tokelauan-hired workers decided to claim "squatters' rights" to the atoll, by virtue of having lived on it year-round. After Alexander Jennings evicted 56 workers and their families from the island, the governor of American Samoa intervened. By executive order, the governor acknowledged Jennings' proprietary rights to Swains Island, while instituting a system of labor contracts and a local governmental structure to protect the rights of his employees.[6] The islanders were also guaranteed a representative in the territorial legislature.

Recent sovereignty and trade issues

On 25 March 1981, New Zealand, of which Tokelau is a dependency, confirmed U.S. sovereignty over Swains Island in the Treaty of Tokehega, under which the United States surrendered its territorial claims to the other islands of Tokelau. In the draft constitution that was the subject of the Tokelau self-determination referendum, 2006, however, Swains Island is claimed as part of Tokelau.[22] As of March 2007, American Samoa has not yet taken an official position, but the Governor of American Samoa Togiola Tulafono has said he believes that his government should do everything it can to retain control of the island.[23]

In 2007 Tokelau's regional parliament, the General Fono, considered the adoption of a new flag for their nation which showed a map depicting Swains Island, as a fourth star in addition to three others, at a proportional distance to that of the others. Ultimately a compromise was adopted whereby the four stars were retained, but with the arrangement and proportionality suggestive of the Southern Cross.[citation needed]

During a recent[timeframe?] visit to Tokelau, Alexander Jennings, representative of Swains Island to the American Samoa legislature, indicated a desire for better trade links between Swains and its neighbor.[24] The head of government of Tokelau, Kuresa Nasau, was reported[by whom?] to be "interested," and further talks were anticipated.

Cyclone Percy 2005

In February 2005, Cyclone Percy struck the island, causing widespread damage and virtually destroying the village of Taulaga, as well as the old Jennings estate at Etena. Only seven people were on the island at the time.[25] Coast Guard airdrops ensured that the islanders were not left without food, water and other necessities. A United States Coast Guard visit in March 2007 listed 12 to 15 inhabitants, and showed that the island's trees had largely survived Percy's wrath.[4]

Power and radio issues

Due to its remoteness, Swains Island is considered a separate amateur radio "entity" and several visits have been made by ham operators. The 2007 amateur radio "DXpedition", with call sign N8S, made more than 117,000 contacts worldwide. This set a new world record for an expedition using generator power and tents for living accommodations, since broken by the 2012 DXpedition to Malpelo Island.[26]

In 2012, Swains Island hosted the DXpedition NH8S; this group arrived on September 5, 2012 and departed on September 19, 2012. A total of 105,455 radio contacts were made.

Island government

According to the Interior Department survey cited above, Swains Island is governed by the American Samoa "government representative", a village council, a pulenu'u (civic head of the village), and a leoleo (policeman). Swains' officials have the same rights, duties, and qualifications as in all of the other villages of American Samoa. Neither the proprietor of Swains Island nor any employee of his may serve as government representative.

The government representative has the following duties:

- to act as the Governor's representative on Swains Island

- to mediate between employees and their employer

- to enforce those laws of the United States and of American Samoa which apply on Swains Island

- to enforce village regulations

- to keep the Governor advised of the state of affairs on Swains Island, particularly on the islanders' health, education, safety, and welfare

- to ensure that the Swains Islanders continue to enjoy the rights, privileges and immunities accorded to them by the laws of the United States and of American Samoa

- to ensure that the proprietary rights of the owner are respected

The government representative has the following rights, powers and obligations:

- to make arrests

- to quell breaches of the peace

- to call meetings of the village council to consider special subjects

- to take such actions as may be reasonably necessary to implement and render effective his duties

Swains' village council consists of all men of sound mind over the age of twenty-four. According to the federal census in 1980, five men fell into this category.

Swains Island sends one non-voting delegate to the American Samoan territorial legislature. In March 2007, this office was held by Alexander Jennings.

The Jennings dynasty

Styling themselves "leaders", or "proprietors", members of the Jennings family ruled Swains Island virtually independent of any outside authority from 1856 to 1925. After 1925, while retaining proprietary ownership of the island, they were subject to the jurisdiction of the U.S. territory of American Samoa.

Jennings who ruled as semi-independent "proprietors":

- 13 October 1856 – 4 December 1878: Eli Hutchinson Jennings, Sr. (1814–1878)

- 4 December 1878 – 25 October 1891: Malia Jennings, his Samoan widow (d. 1891)

- 25 October 1891 – 24 October 1920: Eli Hutchinson Jennings, Jr., (1863–1920) son of Eli, Sr. and Malia (1863–1920) Referred to by Robert Louis Stevenson as "King Jennings" during a visit to the island.

- 24 October 1920 – August 1921: Ann Eliza Jennings Carruthers (1897–1921) Jointly with sibling, Alexander Hutchinson Jennings; both children of Eli Jr.

- 24 October 1920 – 4 March 1925: Alexander Hutchinson Jennings III

Jennings who ruled under direct American jurisdiction:

- 4 March 1925 – Unknown date in 1940s: Alexander Hutchinson Jennings III

- Unknown Dates between 1940–1954: Alexander E. Jennings

- 1954 to Present: Local government instituted by American Samoa. However, the island is still owned by the Jennings extended family.

In popular culture

Swains Island: One of the Last Jewels of the Planet (2014) is the first American Samoa film to make an entry at the renowned Blue Ocean Festival in Florida. The 90-minute documentary is directed and narrated by Jean-Michael Cousteau, and showcases the ecological and cultural aspects of Swains Island, including the coral reef, the tapua, the lagoon, and village.[27][28][29]

The band Te Vaka has written a song called Haloa Olohega ("Poor Olohega" in Tokelauan), complaining about the loss of the island for Tokelau.[30]

References

- ^ "What is the difference between nationality and citizenship?". The Economist. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ^ Monmonier, Mark (2010). No Dig, No Fly, No Go: How Maps Restrict and Control. University of Chicago Press. p. 81. ISBN 9780226534633.

- ^ "The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Retrieved 2014-03-11.

- ^ a b [1]

- ^ "Doug Faunt's Journal". N6tqs.livejournal.com. Archived from the original on 2015-04-13. Retrieved 2014-03-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "doi.gov". Archived from the original on 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b [2] Archived January 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [3] Archived October 16, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [4] Archived July 23, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [5] Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "uscg.mil". Archived from the original on 2008-04-17. Retrieved 2007-10-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "American Samoa Company Develops Breadfruit Flour Production Process". Pacific Islands Report. 8 November 2016.

- ^ "Jump-starting Swains' economy". Samoa News. 12 September 2017.

- ^ Maude, H.E. (1968). Of Islands & Men. Oxford University Press. pp. 74, 75.

- ^ Sharp, Andrew (1960). The Discovery of The Pacific Islands. Oxford University Press. pp. 61, 62.

- ^ "Journal of William L. Hudson, comdg. U.S. Ship Peacock, one of the vessels attached to the South Sea Surveying and Exploring Expedition under the command of Charles Wilkes Esq. 1838-1842. (American Museum of Natural History)".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "File no. 811.0141q/14, Central Decimal File of the Dept. of State/Nara". 1914.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Lufkin and Swain family papers..., Bancroft Library, UC, Berkely, Ca. - Banc MSS 68/122 c.".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Dehner, Steve (2017). "The "Forged" Discovery of Swains Island: The Nantucket Connection I".

- ^ a b Page 213 in Jimmy M. Skaggs (1994), The Great Guano Rush: Entrepreneurs and American Overseas Expansion. ISBN 978-0-312-10316-3.

- ^ Gordon L. Rottman (2002). World War II Pacific Island Guide: A Geo-military Study. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-313-31395-0.

- ^ "Tokelau calls for return of island". One News. 15 February 2006. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- ^ "American Samoa governor ready to resist Tokelau's claim to Swains Island". Radio New Zealand International. 26 March 2007. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- ^ [6] [dead link]

- ^ [7] Archived July 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "N8S Home Page". Yt1ad.info. Retrieved 2014-03-11.

- ^ http://www.radionz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/259084/american-samoa-ocean-film-wins-award

- ^ http://samoanews.com/%E2%80%9Cswains-island-one-last-jewels-planet%E2%80%9D-wins-festival-award

- ^ http://www.keyt.com/news/film-festival/sbiff-movie-spotlight-swains-island/65307158

- ^ "Te Vaka". www.tevaka.com. Retrieved 2018-04-28.

External links

- US Dept. of Interior history and description of Swains Island Introduction to Swains Island geography and history.

- "Memorable events on Swains" 2005 Story from the Samoa News about a 1920s visit to Swains Island.

- "A queen mother's last wish" Article in the Honolulu Advertiser about the death of Eliza Jennings Thompson, "queen mother" of Swains Island.

- American Samoa, its districts and unorganized islands, United States Census Bureau

- Alert for Cyclone Percy Gives 2005 population.

- History of Swains Island

- WorldStatesmen- American Samoa

- Tokelau looks to independence

- An account of a visit to Swain's Island in the 1960s