1924 British Mount Everest expedition

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2008) |

The British Mount Everest Expedition 1924 was—after the British Everest Expedition of 1922—the second expedition with the goal of achieving the first ascent of Mount Everest. After two summit attempts in which Edward Norton set a world altitude record, the mountaineers George Mallory and Andrew "Sandy" Irvine disappeared on the third attempt. Their disappearance has given rise to mountaineering history's most notorious unanswered question: whether or not the pair successfully climbed to the summit. Mallory's body was found in 1999 but the resulting clues did not provide conclusive evidence as to whether the summit was reached.

Background and motivation

At the beginning of the 20th century, the British participated in contests to be the first to reach the North and South Poles, without success. A desire to restore national prestige led to scrutiny and discussion of the possibility of "conquering the third pole" – making the first ascent of the highest mountain on Earth.

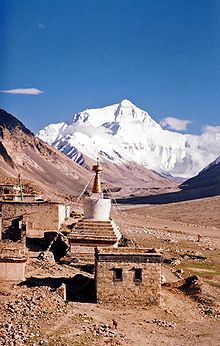

The southern side of the mountain, which is accessible from Nepal and today is the standard climbing route, was unavailable as Nepal was a "forbidden country" for westerners. Going to the north side was politically complex: it required the persistent intervention of the British-Indian government with the Dalai Lama regime in Tibet to allow British expedition activities. At the time, Tibet was one focus of the "Great Game", a struggle between Russia and Britain for military, political and commercial dominance in Central Asia.

A major handicap of all expeditions to the north side of Mount Everest is the tight time window between the end of winter and the start of the monsoon rains. To travel from Darjeeling in northern India over Sikkim to Tibet, it was necessary to climb high, long snow-laden passes east of the Kangchenjunga area. After this first step, a long journey followed through the valley of the Arun River to the Rongbuk valley near the north face of Mt. Everest. Horses, donkeys, yaks, and dozens of local porters provided transport. The expeditions arrived at Mt. Everest in late April and only had until June before the monsoon began, allowing only six to eight weeks for altitude acclimatization, setting up camps, and the actual climbing attempts.

Preparations

Two other British expeditions preceded the 1924 effort. The first in 1921 was an exploratory expedition led by Harold Raeburn which described a potential route along the whole northeast ridge. Later George Mallory proposed a longer modified climb to the north col, then along the north ridge to reach the northeast ridge, and then on to the summit. This approach seemed to be the “easiest” terrain to reach the top. After they had discovered access to the base of the north col via the eastern Rongbuk valley, the complete route was explored and appeared to be the superior option. Several attempts on Mallory's proposed route occurred during the 1922 expedition.

After this expedition, insufficient time for preparation and a lack of financial means prevented an expedition in 1923. The Common Everest Committee had lost some 700 pounds in the bankruptcy of the Simla Bank. So the third expedition was postponed until 1924.[1][2]

Like the two earlier expeditions, the 1924 expedition was also planned, financed and organized by the membership of the Royal Geographic Society and the Alpine Club. The Mount Everest Committee which they formed used military strategies with some military personnel.

One important change was the role of the porters. The 1922 expedition recognized several of them were capable of gaining great heights and quickly learning mountaineering skills. The changed climbing strategy which increased their involvement later culminated in an equal partnership of Tenzing Norgay for the first known ascent in 1953 together with Edmund Hillary. The gradual reversal in the system of “Sahib - Porter” from the earliest expeditions eventually led to a “professional - client” situation where the Sherpa “porters” are the real strong mountaineering professionals and the westerners mainly weaker clients. [1]

Like the 1922 expedition, the 1924 expedition also brought bottled oxygen to the mountain. The oxygen equipment had been improved during the two intervening years but was still not very reliable. Also there was no real clear strategy whether to use this assistance. It was the start of a discussion which still lasts today: the “sporting” arguments intend to climb Everest “by fair means” without the technical measure which reduces the effects of high altitude by a couple thousand metres.

Participants

The expedition used the same leader as the 1922 expedition, General Charles G. Bruce. He was responsible for managing equipment and supplies, hiring porters and choosing the route to the mountain.

The question of which mountaineers would comprise the climbing party was not an easy one. As a consequences of the First World War, there was a lack of a whole generation of strong young men. George Mallory was again part of the mission, along with Howard Somervell, Edward "Teddy" Norton and Geoffrey Bruce. George Ingle Finch, who had gained the record height in 1922, was proposed as a member but eventually was not included because he was divorced and had accepted money for lectures. He seemed out of place to the elitist folks on the committee, especially the influential Secretary Arthur Hinks who made it clear that for an Australian to be first on Everest was not acceptable as they wanted the climb to be an example of British spirit to lift English morale. Mallory refused to climb again without Finch but changed his mind after being personally persuaded by the British royal family at Hinks' request.[3]

New members of the team were Noel Odell,[4] Bentley Beetham and John de Vars Hazard. Andrew "Sandy" Irvine, an engineering student whom Odell knew from an expedition to Spitsbergen was a so-called "experiment" for the team and a test for “young blood” on the slopes of Mount Everest. Due to his technical expertise, Irvine was able to enhance the capacities of the oxygen equipment, to decrease the weight, and to perform a number of repairs.

The participants were not only selected for their mountaineering abilities. The status of their families and any military experience or university degrees were also factors in the selection procedures. Military experience was of the highest importance in the public image and communication to the newspapers.

The full expedition team consisted - besides a large number of porters - of the following persons:

| Name | Function | Profession |

|---|---|---|

| Charles G. Bruce | head of expedition | soldier (officer, Brigadier) |

| Edward F. Norton | deputy head of expedition, mountaineer | soldier (officer, Lieutenant-Colonel) |

| George Mallory | mountaineer | teacher |

| Bentley Beetham | mountaineer | teacher |

| C. Geoffrey Bruce | mountaineer | soldier (officer, Captain) |

| John de Vars Hazard | mountaineer | engineer |

| R.W.G. Hingston | expedition doctor | medical doctor and soldier (officer, Major) |

| Andrew Irvine | mountaineer | engineering student |

| John B.L. Noel | photograph, movie camera operator | soldier (officer, Captain) |

| Noel E. Odell | mountaineer | geologist |

| E.O. Shebbeare | transportation officer | |

| Dr. T. Howard Somervell | mountaineer | medical doctor |

Journey

At the end of February 1924, Charles and Geoffrey Bruce, Norton and Shebbeare arrived in Darjeeling where they selected the porters from Tibetans and Sherpas. They once again engaged the Tibetan born Karma Paul for translation purposes and Gyalzen for sirdar (leader of the porters) and purchased food and material. At the end of March 1924, all expedition members were assembled and the journey to Mount Everest began. They followed the same route as the 1921 and 1922 expeditions. To avoid overloading the inns, they travelled in two groups and arrived in Yatung at the beginning of April. Phari Dzong was reached on April 5. After negotiations with Tibetan authorities, the main part of the expedition followed the known route to Kampa Dzong while Charles Bruce and a smaller group chose an easier route. During this stage, Bruce was crippled with malaria and was forced to relinquish his leadership role to Norton. On April 23 the expedition reached Shekar Dzong. They arrived at the Rongbuk Monastery on April 28, some kilometres from the planned base camp. The Lama of Rongbuk Monastery was ill and could not speak with the British members and the porters or perform the Buddhist puja ceremonies. The following day the expedition reached the location of the base camp at the glacier end of the Rongbuk valley. Weather conditions were good during the approach but now the weather was cold and snowy.

Planned access route

As the kingdom of Nepal was forbidden to foreigners, the British expeditions before the Second World War could only gain access to the north side of the mountain. In 1921, Mallory had seen a possible route from the Lhakpa La to go to the top. This route follows the eastern edge of the Rongbuk Glacier to the north col. From there, the windy ridges (north ridge, northeast ridge) allow a further climb to the top. The upper northeast ridge imposes a formidable obstacle in the form of three steps, particularly the second step at 8,605 metres (28,230 ft), whose difficulty was unknown in 1924. The second step has a height of 30 metres and a slope of more than 70 degrees. After that point, the ridge route leads to the summit by relatively mild but long slopes.

The first men to travel this route to the summit were the Chinese in 1960 along the northeast ridge. The British since 1922 made their ascent trials significantly down the ridge, crossed the giant north face to the great couloir (later called the “Norton couloir”), ascended along the borderline of the couloir, and then attempted to climb the summit pyramid. This route was unsuccessful until Reinhold Messner followed it for his solo ascent in 1980. The exact route of the Mallory and Irvine ascent is disputed, and it is unknown if either of them reached the summit before death. The traverse of the northern wall slopes was a potential alternative to the ridge route.

Erection of the camps

The positions of the high camps were planned before the expedition took place. Camp I (5400m) was erected as an intermediate camp at the entrance of the eastern Rongbuk Glacier to the main valley. Camp II (about 6000m) was erected as another intermediate camp, halfway to Camp III (advanced base camp, 6400m) at the foot of the icy slopes leading up to the north col.

Supplies were transported by about 150 porters from base camp to advanced base camp. The porters were paid around one shilling per day. A lot of porters disappeared after a short while. At the end of April they expanded the camp positions, a job which was finished in the first week of May.

Further climbing activities were delayed because of a snow storm.[2] On May 15 the expedition members received the blessings of the Lama at the Rongbuk Monastery. As the weather started to improve, Norton, Mallory, Somervell and Odell arrived on May 19 at Camp III. One day later they started to fix ropes on the icy slopes to the north col. They erected Camp IV on May 21 at a height of 7,000 metres (22,970 ft).

Once again the weather conditions deteriorated. John de Vars Hazard remained in Camp IV on the north col with twelve porters and little food. Eventually Hazard was able to climb down, but only eight porters came with him. The other four porters, who had become ill, were rescued by Norton, Mallory and Somervell. The whole expedition returned to Camp I. There, 15 porters who had demonstrated the most strength and competence in climbing were elected as so called “tigers”.[1][2]

Summit attempts

The first attempt was scheduled for Mallory and Bruce, and after that Somervell and Norton would get a chance. Odell and Irvine would support the summit teams from Camp IV while Hazard provided support from Camp III. The supporters would also form the reserve teams for a third try. The first and second attempts were done without bottled oxygen.[2]

First: Mallory and Bruce

On June 1, 1924 Mallory and Bruce began their first attempt from the north col, supported by nine "tiger" porters. Camp IV was situated in a relatively protected space some 50m below the north col; when they left the shelter of the ice walls they were exposed to harsh, icy winds. Before they were able to install Camp V at 7,700 metres (25,260 ft), four porters abandoned their loads and went down. While Mallory erected the platforms for the tents, Bruce and one tiger retrieved the abandoned loads. The following day, three tigers also objected to climbing higher, and the attempt was aborted without erecting Camp VI as planned at 8200m. Halfway down to Camp IV, the first summit team met Norton and Somervell who just started their attempt.[1][2]

Second: Norton and Somervell

The second attempt was started on June 2 by Norton and Somervell with the support of six porters. They were astonished to see Mallory and Bruce descending so early and wondered if their porters would also refuse to continue beyond Camp V. This fear was partially realized when two porters were sent “home” to Camp IV, but the other four porters and the two English climbers spent the night in Camp V. On the following day, three of the porters brought the materials to establish Camp VI at 8170m in a small niche. The porters were then sent back to Camp IV on the north col.

On June 4 the mountaineers were able to start their summit bid at 6:40 am, later than originally planned. A spilled water bottle caused the delay since the two climbers had to again melt snow for drinking water. Weather seemed to be ideal. After ascending more than 200 metres, they decided to traverse in the north wall, but the altitude effect of low oxygen forced them to stop frequently to rest.

Around 12 o’clock Somervell was no longer able to climb higher. Norton tried to go alone and traversed to the deep valley which leads to the eastern foot of the summit pyramid. This valley was therefore named “Norton couloir” or “great couloir”. During this solo climb, Somervell took one of the most remarkable photographs in mountaineering history. It shows Norton near his high point of 8,573 metres (28,130 ft) where he tried to climb over steep sloppy icy terrain with some spots of fresh snow. This altitude established a world record height on any mountain which was not surpassed for another 28 years until the 1952 Swiss expedition when Raymond Lambert and Tenzing Norgay reached 8,611 metres (28,251 ft) on the south side of Everest.[5]

The foot of the summit pyramid was only 60m above Norton when he decided to turn around because of insufficient time and doubts about his further strength. He re-joined Somervell at 2 pm; and they went down. While following Norton, Somervell suffered a severe problem with a blockage of his lung, and he sat down to await his death. In a desperate last attempt, he pressed his lungs with his arms, and suddenly the blockage was over. Soon after this relief, he recovered and continued down the mountain.

Below Camp V it had turned dark, but they managed to reach Camp IV. They were offered oxygen bottles but their first wish was to drink. As the night progressed, Mallory spoke to Norton about his plan to make a final attempt with oxygen.[1][2]

Third: Mallory and Irvine

While Somervell and Norton ascended, Mallory and Bruce had climbed down to Camp III and returned to the north col with oxygen. Mallory selected Sandy Irvine as his climbing partner for this climb. Since Norton was the expedition leader after the illness of Bruce, and Mallory was the chief climber, he decided not to challenge Mallory’s plan, in spite of his wish to be part of another attempt.

Irvine was not chosen primarily for his climbing abilities, but due to his knowledge of the oxygen equipment. Mallory and Irvine had also become friends since they shared a lot of time aboard ship to India.

On June 5th they were in Camp IV. At 8:40 a.m. of the following day they reached Camp V with five porters, and on June 7th ascended to Camp VI. Odell and one porter went to Camp V to support the summit team. Shortly after Odell's arrival in Camp V, four porters of the Mallory team came down, sent by Mallory. They handed over a message from Mallory to Odell with an estimated time of their arrival on the ridge.

- Dear Noel,

- we'll probably start early to-morrow (8th) in order to have clear weather. It won't be too early to start looking out for us either crossing the rockband under the pyramid or going up skyline at 8.0 p.m.

- Your ever

- G Mallory

Mallory really meant 8 a.m., not 8 p.m.[6][1].

On the morning of June 8th, Odell started an ascent to gain a good viewpoint of the ridge. Around him the mountain was covered by mist so he could not see Mallory and Irvine, but he anticipated better views higher on the mountain. At 7900m he climbed on top of a rock. Suddenly the mist disappeared for a short while around 12:50 p.m. Odell noted in his diary that he saw Mallory and Irvine on the ridge when they reached the foot of the summit pyramid.[7]. In a first report on July 5th to The Times he clarified this view. He saw the summit, the ridge and the final pyramid of Mt. Everest. His eyes caught a tiny black dot which moved on a snowy area below the northeast ridge. A second black dot was moving toward the first one.[8].

Odell's initial option was that the two climbers had reached the base of the Second Step.[9] He was concerned because Mallory and Irvine seemed to be far behind the time schedule. After this sighting, Odell climbed to Camp VI where he found the tent in chaotic disorder. After a short while he ascended further, trying to attract the attention of the two climbers by whistling and shouting to lead them back to their camp and to support their orientation. When Odell return to Camp VI the snow had stopped. He scanned the mountain for Mallory and Irvine but could not see anyone.

As Mallory intended to descend quickly, he had advised Odell to leave Camp VI and go to Camp IV on the north col. Odell arrived at 6:45 p.m. On June 9 Odell again climbed up the mountain together with two porters as they had not seen any sign from Mallory and Irvine. Around 3:30 p.m. they arrived at Camp V and stayed for the night. The following day Odell again went alone to Camp VI which he found unchanged. Then he climbed up to around 8500m but could not see any trace of the two missing climbers. In Camp VI he put two sleeping bags in a T form on the snow which was the signal for "No trace can be found, Given up hope, Awaiting orders" to the advanced base camp. After this Odell climbed down to Camp IV. In the morning of June 11 they started to leave the mountain by climbing down the icy slopes of north col to end the expedition. Five days later they said goodbye to the Lama at Rongbuk Monastery.[1][2]

After the expedition

The expedition participants erected a memorial pyramid in honor of the men who had died in the 1920s on Mount Everest. Mallory and Irvine became national heroes. Magdalene College, one of the constituent college's of the University of Cambridge, where Mallory had studied, erected a memorial stone in one of it's court's - a court renamed for Mallory. The University of Oxford, where Irvine studied, erected a memorial stone in his memory. In St Paul's Cathedral a ceremony took place which was attended by King George V and other dignitaries, as well as the families and friends of the climbers.

The next expedition did not occur until 1933—after the deaths of the Sherpas in 1922 and the British in 1924 the Dalai Lama had not allowed access for further expeditions. There were also some cases of the British hunting animals in the upper Rongbuk valley, against Buddhist law.

Odell's Sighting of Mallory and Irvine

Soon after the expedition, Odell was privately certain that Mallory and Irvine had reached the summit of Mount Everest. Key to this belief was the spot where he had seen the two climbers, and his evaluation of their fitness and strength. However, Odell varied his opinion on several occasions as to the very spot where he had seen the two black dots. Directly after the expedition he was of the opinion that he had seen them at the foot of the Third Step and the summit pyramid. The Third Step is no real hindrance for climbers as they can also easily walk around it. From Odell's position it would have been possible to identify it clearly. In the expedition report he wrote that the climbers were on the second-to-last step below the summit pyramid, indicating the famous and more difficult Second Step. He later mentioned the possibility that he had seen them on the First Step.[10] Odell's account of the weather situation also varied. At first, he described that he could see the whole ridge and the summit. Later, he said that only a part of the ridge was free of mist. After viewing photographs of the 1933 expedition, Odell again said that he might have seen the two climbers at the Second Step. In 1988, he admitted that since 1924 he had never been clear about the exact location along the northeast ridge where he had seen the black dots.[1]

Findings

| Green line | Normal route, mainly the Mallory route 1924, with high camps at 7700 and 8300 m, the current camp at 8300m is a little bit west (2 triangles) |

| Red line | Great Couloir or Norton Couloir |

| dark blue line | Hornbein Couloir |

| †1 | Mallory found 1999 |

| ? | 2nd step, foot at 8605m, height ca. 30 m, difficulty 5.9 or 5.10 |

| a) | spot at ca. 8325 m which was George Ingle Finch’s highest point with oxygen, 1922 |

| b) | spot at 8572 m at the western border of the couloir which Edward Felix Norton reached in 1924 without artificial oxygen |

Odell discovered the first evidence which might reveal something about the climb of Mallory and Irvine among the equipment in camps V and VI. In addition to Mallory's compass, which normally was a critical component for climbing activities, he discovered some oxygen bottles and spare parts. This situation indicated that there was a problem with the oxygen equipment which might have caused a delayed start in the morning. An electric lamp also remained in the tent - it was still in working order when it was found by the Ruttledge expedition nine years later.

During their climbing trials, Harris and Wager, both participants in the 1933 British Mount Everest expedition, found the ice axe of Irvine some 230 metres east of the First Step and 20 metres below the ridge. This location raises additional questions: the area is not very dangerous for climbers, so a fall was unlikely, but given the critical need of an ice axe, no climber would intentionally leave it there.

On the second summit climb of the Chinese in 1975, the Chinese mountaineer Wang Hong Bao saw an "old English dead body" at 8,230 m (27,001 ft). This news was never officially released, but this report to a Japanese climber led to the the first Mallory and Irvine Research Expedition in 1986, which was unsuccessful due to bad weather.

In 1999, a new search expedition was started, led by Eric Simonson who had seen some very old oxygen bottles near the First Step during his first summit climb in 1991. These bottles were again found in 1999 and could be related to Mallory and Irvine. The expedition also tried to reproduce Odell's position when he had seen Mallory and Irvine. The mountaineer Andy Politz later reported that they could clearly identify each of the three steps without any problems.

The most remarkable finding was the corpse of George Leigh Mallory at a height of 8,159 metres (26,768 ft). The conditions of the body indicated that he had not tumbled very far. His injuries were such that a descent was impossible: the right leg was broken, and there was a substantial head injury. Since the unbroken leg was held over the broken one, as if to protect it, he may have been conscious after his fall. There was no oxygen equipment near the body - the oxygen bottles would have been empty by this time and discarded at a higher altitude to avoid the heavy load. Mallory was not wearing snow goggles, although a pair was stored in his vest, which may indicate that he was on the way back by night. However, a contemporary photograph shows he had two sets of goggles when he started his summit climb. The image of his wife Ruth which he intended to put on the summit was not in his vest. He carried the picture throughout the whole expedition—a sign that he might have reached the top. Since his Kodak pocket camera was not found, there is no proof of a successful climb to the summit.[1][6]

First ascent?

From 1924 to this day, there are supporting claims and rumors that Mallory and Irvine had been successful and so were actually the first to summit Mount Everest. One counter argument claims that their fleece, vests and trousers were too poor quality, which is challenged by Graham Hoyland. In 2006, he climbed to the summit in an exact reproduction of Mallory's original clothing. He said that it functioned very well and was quite comfortable, but the weather on Hoyland's summit day was a lot better than on the potential summit day of Mallory and Irvine.

Odell's sighting is of especially high interest. The description of Odell's sighting and the current knowledge indicate Mallory's completion of the Second Step is unlikely. This wall cannot be climbed as fast as described by Odell. Only the first and the third step can be climbed quickly. Odell said that they were at the foot of the summit pyramid, which contradicts a location at the First Step, but it is unlikely the pair could have started early enough to reach the Third Step by 12:50 p.m. Since the First Step is far away from the Third Step, confusing them is also not likely. One suggestion proposes Odell confused a sighting of birds for climbers—a result which occurred with Eric Shipton in 1933.

This speculation also involves theories concerning whether Mallory and Irvine could have managed to climb the Second Step. Conrad Anker led an experiment to free climb this section without using the “Chinese ladder” for assistance, since that equipment was not installed in 1924. In 1999, he did not manage a complete free climb as he put one foot briefly on the ladder when he became exhausted. But two other climbers managed to climb the Second Step freely without the ladder. These climbs indicate that Mallory, a strong climber, may also have been able to reach the top of the Second Step.

An argument against the possible summit claim is the long distance from high camp VI to the summit. It is normally not possible to reach the summit before dark after starting in daylight. It was not until 1990 that Ed Viesturs was able to reach the top from an equivalent distance as Mallory and Irvine planned. In addition, Viesturs knew the route, while for Mallory and Irvine it was completely unknown territory. Finally, Irvine was not an experienced climber and it is considered unlikely that Mallory had put his friend into such danger or would have aimed for the summit without calculating the risks.

How and where exactly the two climbers lost their lives is still unknown.[1]

Modern climbers who take a very similar route start their summit bid from high camp at 8,300 m (27,230 ft) around midnight to avoid the risk of a second night on the descent or a highly risky bivouac without the protection of a tent. They also use headlamps during the dark, a technology which was not available for the early British climbers.

See also

- British Mount Everest Expedition 1922

- Timeline of climbing Mount Everest

- The Last Witness (Noel Odell) [1]

Bibliography

- Breashears, David (2000). Mallorys Geheimnis. Was geschah am Mount Everest?. Steiger. ISBN 3-89652-220-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Hemmleb, Jochen (2001). Die Geister des Mount Everest: Die Suche nach Mallory und Irvine. Frederking u. Thaler. ISBN 3-89405-108-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Hemmleb, Jochen (2002). Detectives on Everest. The Story of the 2001 Mallory & Irvine Research Expedition (1st ed.). Seattle: The Mountaineers Books. ISBN 0-89886-871-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Holzel, Tom (1999). In der Todeszone. Das Geheimnis um George Mallory und die Erstbesteigung des Mount Everest. Goldmann Wilhelm GmbH. ISBN 3-442-15076-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Norton, Edward Felix (2000). Bis zur Spitze des Mount Everest - Die Besteigung 1924. Translated by Willi Rickmer Rickmers. Berlin: Sport Verlag. ISBN 3-328-00872-1.

- Unsworth, Walt (2000). Everest - The Mountaineering History (3rd ed.). Bâton Wicks. ISBN 978-1898573401.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Breashears, Salkeld: Mallorys Geheimnis

- ^ a b c d e f g The Geographical Journal, Nr.6 1924

- ^ The Advertiser Treachery at the top of the World Pg 3 February 21, 2009

- ^ "picture of Noel Odell" (JPEG). Retrieved 2009-03-28.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Unsworth, pp. 289-290

- ^ a b Holzel, Salkeld: In der Todeszone

- ^ Breashears, Salkeld: Mallorys Geheimnis, page 173

- ^ Breashears, Salkeld: Mallorys Geheimnis, page 174

- ^ Norton: Bis zur Spitze des Mount Everest, page 124

- ^ Norton: Bis zur Spitze des Mount Everest, pp. 124/125