42 (film)

| 42 | |

|---|---|

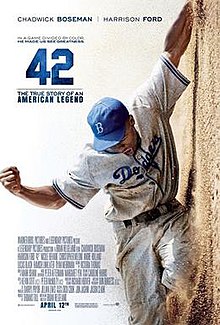

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Brian Helgeland |

| Written by | Brian Helgeland |

| Produced by | Thomas Tull |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Don Burgess |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | Mark Isham |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 128 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $31–40 million[2][3] |

| Box office | $97.5 million[3] |

42 is a 2013 American biographical sports film written and directed by Brian Helgeland. The plot follows baseball player Jackie Robinson, the first black athlete to play in Major League Baseball (MLB) during the modern era. The title of the film is a reference to Robinson's jersey number,[4] which was universally retired across all MLB teams in 1997.[5] The ensemble cast includes Chadwick Boseman as Robinson, alongside Harrison Ford, Nicole Beharie, Christopher Meloni, André Holland, Lucas Black, Hamish Linklater, and Ryan Merriman in supporting roles.[6]

The project was announced in June 2011, with principal photography taking place in Macon, Georgia and Atlanta Film Studios Paulding County in Hiram as well as in Alabama and Chattanooga, Tennessee.[7]

42 was theatrically released in North America on April 12, 2013.[8] The film received generally positive reviews from critics, who praised the performances of Boseman and Ford, and it grossed $97.5 million on a production budget of $31–40 million.

Plot

[edit]In 1945, Brooklyn Dodgers owner Branch Rickey meets with sportswriter Wendell Smith regarding wanting to recruit a black baseball player for his team; Wendell suggests Jackie Robinson of the Kansas City Monarchs. Robinson accepts, but is warned by Rickey that he must control his temper despite the adversities he will face while breaking the color line. Robinson proposes to his girlfriend, Rachel, and she accepts. Robinson earns a spot with the Montreal Royals, the AAA affiliate of the Brooklyn farm system. After performing well his first season, he advances to the Dodgers and is trained as a first baseman. Some of the Dodgers players draft a petition refusing to play with Robinson, but manager Leo Durocher rebuffs them. However, Durocher is suspended by Baseball Commissioner Happy Chandler due to his extramarital affair. Burt Shotton takes over as manager. Robinson and Rachel have their first child.

In a game against the Philadelphia Phillies, manager Ben Chapman taunts Robinson with racial epithets. With encouragement from Rickey, Robinson scores the winning run. When Chapman's behavior toward Robinson generates negative press for the team, Phillies' general manager Herb Pennock requires him to pose with Robinson for magazine photos. Later, Pee Wee Reese comes to understand what kind of pressure Robinson is facing, and makes a public show of solidarity, standing with his arm around Robinson's shoulders before a hostile crowd at Crosley Field in Cincinnati, silencing them.

In a game against the St. Louis Cardinals, Enos Slaughter spikes Robinson on the back of the leg with his cleats. The Dodgers want revenge, but Robinson calms them and insists they focus on winning the game. Robinson's home run against Pittsburgh Pirates pitcher Fritz Ostermueller, who had earlier hit him in the head, helps the Dodgers clinch the National League pennant, sending them to the 1947 World Series. An epilogue reveals Robinson and his teammates’ future involvements, as well as others.

Cast

[edit]- Chadwick Boseman as Jackie Robinson

- Harrison Ford as Branch Rickey

- Nicole Beharie as Rachel Robinson

- Christopher Meloni as Leo Durocher

- André Holland as Wendell Smith

- Alan Tudyk as Ben Chapman

- Lucas Black as Pee Wee Reese

- Hamish Linklater as Ralph Branca

- Brett Cullen as Clay Hopper

- Ryan Merriman as Dixie Walker

- Brad Beyer as Kirby Higbe

- Gino Anthony Pesi as Joe Garagiola

- T. R. Knight as Harold Parrott

- Max Gail as Burt Shotton

- Toby Huss as Clyde Sukeforth

- James Pickens Jr. as Mr. Brock

- Mark Harelik as Herb Pennock

- Derek Phillips as Bobby Bragan

- Jesse Luken as Eddie Stanky

- John C. McGinley as Red Barber

- Dusan Brown as young Ed Charles

- Linc Hand as Fritz Ostermueller

- Matt Clark as Luther

- Peter MacKenzie as Happy Chandler

- C. J. Nitkowski as Dutch Leonard

- Peter Jurasik as Hotel Manager

- Jeremy Ray Taylor as Boy

- Colman Domingo as Lawson Bowman

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]Spike Lee planned to write and direct Jackie Robinson based on the life of Robinson and had it set up at Turner Pictures under his 40 Acres and a Mule Filmworks in 1995. The studio wanted to release it in 1997 to coincide with the 50th anniversary of Robinson's breaking of the color barrier, and courted Denzel Washington to star,[9] but the project fell apart in 1996 over creative differences. In March 1997, Lee found favor with Columbia Pictures, who signed him to a three-year first-look deal. Columbia President Amy Pascal reflected that it would bring "enormous potential for Spike to reach audiences that are not traditionally associated with Spike Lee movies."[10] The project eventually fell apart, but in 2004 Robert Redford set up a separate biopic as producer with Deep River Productions, as well as his own production company, Wildwood Productions. Redford also intended to co-star as Branch Rickey,[11] and Howard Baldwin joined as producer the following year.[12] In June 2011, it was announced that Legendary Pictures would develop and produce a Jackie Robinson biopic with Brian Helgeland on board to write and direct, under a distribution deal with Warner Bros. Legendary collaborated with Robinson's widow, Rachel Robinson, to ensure the authenticity of her husband's story. She had previously been involved with Redford's project.[13]

Filming

[edit]42 was filmed primarily in Macon, Georgia; Birmingham, Alabama; and Chattanooga, Tennessee. Some interior scenes were shot at Atlanta Film Studios Paulding County in Hiram, Georgia.[14]

Most of the interior stadium shots were filmed in Engel Stadium in Chattanooga, while some were shot at historic Rickwood Field in Birmingham, which also served as the set for game-action scenes at Forbes Field, Roosevelt Stadium, and Shibe Park, as well as itself in the film's opening. Using old photographs and stadium blueprints, Ebbets Field, Shibe Park, The Polo Grounds, Crosley Field, Sportsman’s Park, and Forbes Field were recreated for the film using digital imagery.[15] Former minor league player Jasha Balcom was Boseman's stunt double for various scenes.[16]

Reception

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

Critical response

[edit]On Rotten Tomatoes, 42 holds an approval rating of 81% based on 197 reviews, with an average rating of 6.90/10. The website's critics consensus reads, "42 is an earnest, inspirational, and respectfully told biography of an influential American sports icon, though it might be a little too safe and old-fashioned for some."[17] On Metacritic, the film holds a weighted average score of 62 out of 100, based on 40 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[18] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film a rare "A+" grade.[19][20][21]

Richard Roeper wrote, "This is a competent but mostly unexceptional film about a most extraordinary man."[22] Lisa Kennedy, of the Denver Post, lauded the film, saying "This story inspires and entertains with a vital chapter in this nation's history."[23][24] Conversely, Peter Rainer, of The Christian Science Monitor, criticized the film as "TV-movie-of-the-week dull.... Robinson's ordeal is hammered home to the exclusion of virtually everything else in his life."[25]

The film's actors were generally praised, with Owen Gleiberman saying of Ford, "He gives an ingeniously stylized cartoon performance, his eyes atwinkle, his mouth a rubbery grin, his voice all wily Southern music, though with that growl of Fordian anger just beneath it".[26] The Hollywood Reporter commented that Boseman "has the necessary appeal, proves convincing as an athlete and is expressive in spite of the fact that the man he's playing must mostly keep his true feelings bottled up."[27]

Jackie Robinson's widow, Rachel Robinson, was involved in the production of the film and has praised the end result, saying, "It was important to me because I wanted it to be an authentic piece. I wanted to get it right. I didn't want them to make him an angry black man or some stereotype, so it was important for me to be in there. ... I love the movie. I'm pleased with it. It's authentic and it's also very powerful."[28]

In 2020, Boseman told Essence Magazine that he spoke with Rachel Robinson while preparing for the role. “When you’re doing a character, you want to know the full landscape. You want to know them spiritually, mentally and physically. So I asked her: were there any physical things that he did that stood out. We sat down for hours and talked about his personality and what his tendencies were,” he recalled of their meeting. “The way he stood, and the way he held his hands in the backfield…all of those physical things I tried to do.”[29]

In a 2023 interview with James Hibberd of The Hollywood Reporter, Ford said Branch Rickey is one of his roles he is most proud of.[30]

Box office and Awards

[edit]42 grossed $95 million in the United States and $2.5 million in other territories, for a worldwide total of $97.5 million, against a production budget of $40 million.[3][31]

The film earned $27.3 million for its opening weekend, the best-ever debut for a baseball-themed film.[21] It then made $17.7 million and $10.7 million on its second and third weekends, finishing second and third, respectively.[32]

After Boseman's death in August 2020, several theater chains, including AMC and Regal, re-released the film in September.[33]

Boseman and Ford received nominations for various awards, including Best Supporting Actor (Ford), Actor in a supporting role (Harrison Ford), and Most Promising Performer (Boseman).[citation needed]

Home media

[edit]42 was released on DVD and Blu-ray on July 16, 2013. This release sold 1,367,939 units ($18,049,084), becoming the 33rd highest-grossing DVD of 2013 in the United States.[34]

Historical inaccuracies and omissions

[edit]Robinson and Rachel Isum became engaged in 1943, while he was still in the United States Army and before he began his professional baseball career, unlike in the film, where he proposes after signing the contract with the Dodgers.[35]

The Dodgers 1947 spring training was in Havana, Cuba, not in Panama, as shown in the film.[36]

The suspension of Leo Durocher was not directly as a result of his affair with Laraine Day, but largely because of his association with "known gamblers."[37]

The scene of Robinson breaking his bat in the dugout tunnel is not based in fact. Both Rachel Robinson and Ralph Branca, film consultant and Dodger pitcher in the dugout that day, say it did not happen. Director Helgeland concurs, explaining that his justification for including the scene was that he felt "there was no way Robinson could have withstood all that abuse without cracking at least once, even if it was in private."[38]

Red Barber would not have broadcast Dodger away games from the opposing team's ballpark in Philadelphia and Cincinnati, as shown in the film. Radio broadcasts of away games in this era were recreated back at the studio from a pitch-by-pitch summary transmitted over telegraph wire from the stadium where the game was being played.[39][40]

In the film, Wendell Smith is said to have been the first black member of the Baseball Writers' Association of America (BBWAA). In reality, Sam Lacy was the first, having joined in 1948.[41]

Pirates pitcher Fritz Ostermueller threw left-handed, not right-handed as in the film. His first-inning pitch hit Robinson on the left wrist, not his head, and he claimed it was a routine brushback pitch without racist intent. There was no fight on the mound afterwards.[42] The climactic scene in which Robinson hit a home run to clinch the National League pennant for the Dodgers came in the top of the fourth inning of the game and did not secure the victory or the pennant (it made the score 1–0, and the Dodgers eventually won 4–2). The Dodgers achieved a tie for the pennant on that day, before winning the pennant the next day.[43]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "42 (12A)". British Board of Film Classification. July 8, 2013. Archived from the original on July 13, 2013. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ "42 (2013) – Financial Information". The Numbers.

- ^ a b c "42 (2013)". Box Office Mojo. April 3, 2013. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- ^ "Film on baseball icon gets it right". Boston Herald. April 11, 2013. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- ^ "Each club's last player to wear iconic No. 42". MLB.com. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ Fordin, Spencer (December 9, 2011) Jackie Robinson movie to star Ford, Boseman. Mlb.mlb.com. Retrieved on April 23, 2013.

- ^ "Review: "42" (***½)". georgiaentertainmentnews.com. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ Calcaterra, Craig (June 4, 2012) The Jackie Robinson movie “42″ to open next April 15. Hardballtalk.nbcsports.com. Retrieved on April 23, 2013.

- ^ Cox, Dan (October 16, 1995). "Turner Pix bows starry slate". Variety. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ Cox, Dan (March 2, 1997). "40 Acres & A Mule to Col". Variety. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- ^ McNary, Dave (July 5, 2004). "Duo in Deep with Par". Variety. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ McNary, Dave (June 20, 2005). "Rodney gets some respect". Variety. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ McNary, Dave (June 1, 2011). "Jackie Robinson biopic takes flight". Variety. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ McAllister, Cameron (April 22, 2013). "Review: "42"". Reel Georgia.

- ^ Fine, Marshall (April 7, 2013). "Film wizard Richard Hoover turns Chattanooga's Engel Stadium into Brooklyn's Ebbets Field in 42". New York Daily News. Mortimer Zuckerman. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- ^ Kepner, Tyler (April 13, 2013). "Immersing Himself to Play a Pioneer". The New York Times. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ "42 (2013)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved November 20, 2022.

- ^ "42 Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ "'A+' CinemaScore Grade Puts Hit '42' In Classy Company – Signaling Longevity at Box Office". TheWrap. April 15, 2013. Retrieved March 2, 2020.

- ^ Snider, Eric (April 23, 2013). "Eric D. Snider's Movie Column: What Is a 'Cinemascore'?". MTV News. Archived from the original on October 7, 2021.

Almost as widely reported yet perhaps more revealing: it earned a rare A+ CinemaScore from audiences.

- ^ a b Smith, Grady (April 14, 2013). "Box office report: '42' knocks it out of the park with $27.3 million; 'Oblivion' huge overseas". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

the latest release to earn a rare "A+" CinemaScore grade, signifying exemplary word-of-mouth among ticket-buyers.

- ^ Roeper, Richard (April 12, 2013). 42 Review. Richard Roeper & the Movies. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ Kennedy, Lisa (April 12, 2013). "Movie review: "42" gives baseball great Jackie Robinson, but also heroism, its due". The Denver Post. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ Korsgaard, Sean CW (April 12, 2013). 42 Archived October 6, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Korsgaard's Commentary. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ Rainer, Peter (April 12, 2013). "'42' is a dull treatment of Jackie Robinson's story". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (April 29, 2013). "42". Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ McCarthy, Tom (April 9, 2013). "42: Film Review". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Haylock, Rahshaun (April 15, 2013). "Rachel Robinson reflects on role in making '42'". FOX Sports Interactive Media. Archived from the original on June 29, 2013. Retrieved May 17, 2013.

- ^ "Chadwick Boseman on Playing Jackie Robinson in '42'". Essence. October 28, 2020. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

- ^ Hibberd, James (February 8, 2023). "Harrison Ford: "I Know Who the F*** I Am"". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ "Looking Back at the Jackie Robinson Film '42' – Society for American Baseball Research". Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- ^ "42".

- ^ Anthony D'Alessandro (September 1, 2020). "Chadwick Boseman's Jackie Robinson Pic '42' To Play This Weekend In Celebration Of Actor's Work". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ "Top-Selling DVDs in the United States 2013". Retrieved October 20, 2024.

- ^ Robinson, Jackie (1995) [1972]. I Never Had It Made. New York: HarperCollins. p. 13. ISBN 0-06-055597-1.

- ^ "SABR.org". Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ "Leo Durocher – Society for American Baseball Research".

- ^ Koltnow, Barry (April 19, 2013). "Viewpoint: Why biopics swing hard and strike out". The Providence Journal. Providence, Rhode Island. p. C3.

- ^ "Transcripts: Show". PRX. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ Williams, Jim; Staff (August 5, 1921). "Baseball Games Re-created in Radio Studios". Modestoradiomuseum.org. Archived from the original on January 6, 2016. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ Litsky, Frank (May 12, 2003). "Sam Lacy, 99; Fought Racism as Sportswriter". The New York Times. Retrieved January 14, 2011.

- ^ Kennedy, Wally (May 5, 2013). "'It didn't happen that way'; Daughter of pitcher in '42' says movie unfair to her father". The Joplin Globe. Joplin, Missouri: Community Newspaper Holdings. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- ^ "MLB Stats, Standings, Scores, History". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- 42 at IMDb

- 42 at Box Office Mojo

- 42 at Beyond Chron

- 2013 films

- Cultural depictions of Jackie Robinson

- 2013 biographical drama films

- 2010s English-language films

- 2010s sports drama films

- African-American biographical dramas

- American baseball films

- American sports drama films

- African-American films

- Biographical films about sportspeople

- Brooklyn Dodgers

- English-language biographical drama films

- English-language sports drama films

- Films about racism in the United States

- Films directed by Brian Helgeland

- Films produced by Thomas Tull

- Films scored by Mark Isham

- Films set in 1945

- Films set in 1946

- Films set in 1947

- Films set in New York City

- Films set in Manhattan

- Films set in Brooklyn

- Films set in California

- Films set in Florida

- Films set in Philadelphia

- Films set in Pittsburgh

- Films set in Cincinnati

- Films set in St. Louis

- Films set in Panama

- Films shot in Alabama

- Films shot in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Films shot in Tennessee

- Legendary Pictures films

- Films with screenplays by Brian Helgeland

- Warner Bros. films

- 2013 drama films

- 2010s American films

- Films about Major League Baseball