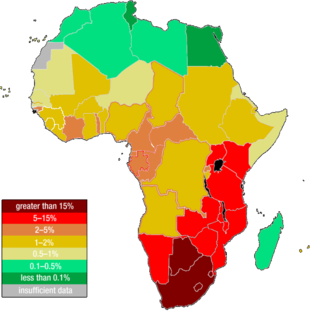

HIV/AIDS in Zimbabwe

over 15% 5-15% 2-5% 1-2% 0.5-1% 0.1-0.5% not available |

HIV and AIDS is a major public health issue in Zimbabwe. The country is reported to hold one of the largest recorded numbers of cases in Sub-Saharan Africa.[1] According to reports, the virus has been present in the country since roughly 40 years ago.[2] However, evidence suggests that the spread of the virus may have occurred earlier.[3] In recent years, the government has agreed to take action and implement treatment target strategies in order to address the prevalence of cases in the epidemic.[4] Notable progress has been made as increasingly more individuals are being made aware of their HIV/AIDS status, receiving treatment, and reporting high rates of viral suppression.[5] As a result of this, country progress reports show that the epidemic is on the decline and is beginning to reach a plateau.[6] International organizations and the national government have connected this impact to the result of increased condom usage in the population, a reduced number of sexual partners, as well as an increased knowledge and support system through successful implementation of treatment strategies by the government.[7] Vulnerable populations disproportionately impacted by HIV/AIDS in Zimbabwe include women and children, sex workers, and the LGBTQ+ population.[8][9][10][11]

Origins and Background

The beginning of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Zimbabwe dates back to the mid-1980's when recorded cases increased by more than 60 percent.[2] The first cases generally resulted in patients seeking assistance for ailments such as severe respiratory infections, or diarrhea associated with weight loss, along with a host of other illnesses. Additionally during this period, children with higher socio-economic status were showing signs of malnutrition associated with poverty, yet the cause of this malnutrition was not yet diagnosed.[citation needed] Growth rates in the earlier stages of the HIV/AIDS epidemic were connected to a lack of available medicine as well as increase in high-risk sexual behavior.[2] By the year 2000, an estimated 25 percent of the population were living with the virus.[12] Today, initial case numbers during this period are considered to be vastly deflated. This is due to a variety of socio-cultural barriers to reporting, as well as the fact that individuals can be asymptomatic for up to two decades before they experience the symptoms that necessitate a diagnosis and treatment.[3]

Prevalence

Transmission Statistics

Despite the severity of the epidemic, HIV/AIDS transmission and prevalence in Zimbabwe has been on the decline.[1] Dr. Peter Piot, head of UNAIDS, said that in Zimbabwe, "The declines in HIV rates have been due to changes in behaviour, including increased use of condoms, people delaying the first time they have sexual intercourse, and people having fewer sexual partners." [13] While reports from organizations such as UNAIDS and the WHO demonstrate a continued decline of HIV/AIDS prevalence in Zimbabwe, many demographics are still at risk of transmitting the virus.[1] According to a study conducted across Sub-Saharan Africa, the most high-risk factors for contracting HIV/AIDS that carry the strongest association with the virus are multiple sexual partners, high numbers of paid sex activity, and the presence of co-infections such as the HSV-2 infection and other sexually transmitted infections.[14] Moreover, it is estimated that the largest transmitter of HIV/AIDS within the population in Zimbabwe continues to be unprotected heterosexual sex.[1]

Mortality Rates

Mortality rates in Zimbabwe attributed to the HIV/AIDS epidemic continue to decline along with diagnosed infections. As of 2018, UNAIDS reported that there had been a 60 percent decrease in AIDS-related deaths since 2010, along with a 24,000 person decrease in new HIV infections.[15] In this same year, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that there was an estimated 19,000 deaths from the virus, a noticeable decrease from previous years.[16] The most common cause of death for people living with HIV/AIDS in Zimbabwe continues to be coexistence of the virus with tuberculosis.[17] Data surrounding a demographic breakdown of deaths related to HIV/AIDS is limited because it is illegal to do sex work or have MSM sex.[18]

Control and Prevention

Treatment

Domestic and international efforts to combat the spread of the virus through expanded access to antiretroviral treatment have contributed to a significant decrease in the prevalence of the virus.[18] A recent review of the government's progress in implementing internationally recommended national treatment policies and implementation measures found that Zimbabwe had made strong progress in its commitments.[19] As of 2018, an estimated 1,086,674 people were receiving antiretroviral treatment.[16] However, access to treatment is still limited for certain groups and demographics, and data on specific populations' access to treatment is scarce due to legal barriers.[18] The Zimbabwe 2018 Human Rights Report filed by the U.S. State Department states that in the time since the initial spread of the virus, a substantial number of citizens living with HIV/AIDS continue to experience societal discrimination today through stigma and employment, that serve as significant barriers to treatment access.[20]

Healthcare Response

In the past century, the national government in Zimbabwe has made efforts to address the epidemic by providing medical assistance to citizens living with HIV/AIDS. Furthermore, Zimbabwe was the first country in Africa to agree to the adherence of the World Health Organization's recommended steps for Antiretroviral Therapy, (ART).[21] However, as of 2016, the organization had only given a partial implementation rating to the government for its adaptation to WHO Key Population Guidelines as well as its implementation of Viral Load Monitoring.[6] Additionally, the national government has passed several laws and policy initiatives with the intent of protecting those living with the virus from discrimination, and to provide them with the necessary medical treatments. Some of these include guaranteed anonymous HIV testing, laws prohibiting the discrimination against those living with HIV/AIDS, as well as government efforts such as the Zimbabwe National Behaviour Change Programme.[22] Nevertheless, those living with HIV/AIDS continue to face social stigma and discrimination in various employment sectors as well as through legislation.[20][23]

International Aid

Foreign assistance and international aid have had a significant role in the proliferation of resources for HIV/AIDS treatment in Zimbabwe. Over sixty-five percent of expenditures on HIV in the country come from foreign donors.[18] USAID has had a notable donor presence in the country since 1980, accounting for over three billion dollars in foreign donor aid as well as partnerships with the national government and other foreign aid donors.[24] The President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), a result of a partnership between the U.S. government and USAID, has resulted in a large portion of foreign donor funds being allocated towards combatting HIV/AIDS. This program has resulted in greater access to treatment and a decrease in annual HIV- related deaths since the program's first implementation in 2006.[25] The largest source of international and domestic funds for HIV response comes from The Global Fund.[26]

Impact on Vulnerable Populations

Women and Children

Women living with HIV/AIDS undergo a significant amount of obstacles due to socio-cultural constraints, and oftentimes gender norms prevent women from accessing healthcare services.[8] Additionally, infants are at risk of contracting the virus through mother-to-child transmission when HIV-positive mothers breastfeed without undergoing antiretroviral therapy.[27] A key study published in 2017 conducting HIV/AIDS research in Zimbabwe, Malawi, and Nigeria reports that "almost 80% of all infant infections [were] attributed to roughly 20% HIV-positive pregnant and breastfeeding women not retained on antiretroviral therapy."[27] However, progress has been made in recent years, as in 2015 the World Health Organization found that 93% of pregnant women had received antiretroviral treatment for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission, (also known as PMTCT).[6] Furthermore, the number of children aged 0–14 living with the virus is estimated to be at 84,000 which is notably lower than men aged 15 and over living with HIV/AIDS (490,000) or women (730,000).[15] However, recent studies show that there are a variety of exceptions to these trends associated with socioeconomic status, as children in rural Zimbabwe that are "HIV-exposed and uninfected" have a 40% higher chance of death than other HIV-exposed children.[9]

Sex Workers

Sex workers in Zimbabwe face disproportionate levels of discrimination that impede their ability to access treatment options.[10] The majority of sex workers diagnosed with HIV/AIDS do not follow through with treatment options such as antiretroviral therapy upon diagnosis. Of those that utilize referrals, attrition rates are notoriously high and only a small number of individuals attend more than one appointment.[28] According to a recent study of 15 participants in Bulawayo, male sex workers in Zimbabwe reported experiencing additional barriers to HIV/AIDS assistance due to the increased stigma of homosexuality and sex work.[29]

LGBTQ+ Community

Sexual relations between men are illegal in Zimbabwe according to Section 73 of the Criminal Law Act.[23] Furthermore, the gay community is not formally recognized by the government as a key population for HIV prevention and care.[29] The non-governmental organization GALZ reports that official statistics for same-sex transmission are not collected by the government.[30] Restrictive aspects within the legal system combined with stigmatizing social norms pose barriers to treatment access for these communities.[31] A 2016 study addressing access to general health services in Zimbabwe suggests that further education on LGBTQ+ issues in the healthcare sector as well as sensitivity training for clinical interviewers are crucial to address existing barriers to treatment for the community.[32]

References

- ^ a b c d "HIV and AIDS in Zimbabwe". Avert. 2015-07-21. Retrieved 2020-05-03.

- ^ a b c Chingwaru, Walter; Vidmar, Jerneja (2018-02-01). "Culture, myths and panic: Three decades and beyond with an HIV/AIDS epidemic in Zimbabwe". Global Public Health. 13 (2): 249–264. doi:10.1080/17441692.2016.1215485. ISSN 1744-1692. PMID 27685780.

- ^ a b Levy, Jay A. (November 1993). "HIV pathogenesis and long-term survival". AIDS. 7 (11): 1401–1410. doi:10.1097/00002030-199311000-00001. ISSN 0269-9370. PMID 8280406.

- ^ "90-90-90: treatment for all". UNAIDS. Retrieved 2020-05-03.

- ^ "Zimbabwe 90-90-90 progress". Avert. 2018-09-18. Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- ^ a b c "HIV country profiles". WHO. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- ^ "2016 Progress reports submitted by countries". UNAIDS. Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- ^ a b Skovdal, Morten; Campbell, Catherine; Nyamukapa, Constance; Gregson, Simon (2011). "When masculinity interferes with women's treatment of HIV infection: a qualitative study about adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Zimbabwe". Journal of the International AIDS Society. 14 (1): 29. doi:10.1186/1758-2652-14-29. ISSN 1758-2652. PMC 3127801. PMID 21658260.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Evans, Ceri; Chasekwa, Bernard; Ntozini, Robert; Majo, Florence D.; Mutasa, Kuda; Tavengwa, Naume; Mutasa, Batsirai; Mbuya, Mduduzi N. N.; Smith, Laura E.; Stoltzfus, Rebecca J.; Moulton, Lawrence H. (2020). "Mortality, HIV transmission and growth in children exposed to HIV in rural Zimbabwe". Clinical Infectious Diseases. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa076. PMID 31974572.

- ^ a b Baral, Stefan; Beyrer, Chris; Muessig, Kathryn; Poteat, Tonia; Wirtz, Andrea L; Decker, Michele R; Sherman, Susan G; Kerrigan, Deanna (2012-07-01). "Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 12 (7): 538–549. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70066-X. ISSN 1473-3099. PMID 22424777.

- ^ Krishan, Kewal; Dehal, Neelam; Singh, Amarjeet; Kanchan, Tanuj; Rishi, Praveen (2018-12-12). "'Getting to zero' HIV/AIDS requires effective addressing of HIV issues in LGBT community". La Clinica Terapeutica. 169 (6): e269–e271. doi:10.7417/CT.2018.2090. ISSN 1972-6007. PMID 30554245.

- ^ Terceira, Nicola; Gregson, Simon; Zaba, Basia; Mason, Peter (2003-01-01). "The contribution of HIV to fertility decline in rural Zimbabwe, 1985-2000". Population Studies. 57 (2): 149–164. doi:10.1080/0032472032000097074. ISSN 0032-4728. PMID 12888411.

- ^ Department Of State. The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affairs. "Country Profile: Zimbabwe". 2001-2009.state.gov. Retrieved 2020-05-11.

- ^ Chen, Li; Jha, Prabhat; Stirling, Bridget; Sgaier, Sema K.; Daid, Tina; Kaul, Rupert; Nagelkerke, Nico (2007-10-03). "Sexual Risk Factors for HIV Infection in Early and Advanced HIV Epidemics in Sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic Overview of 68 Epidemiological Studies". PLOS ONE. 2 (10): e1001. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2.1001C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001001. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 1994584. PMID 17912340.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b "Zimbabwe". UNAIDS. Retrieved 2020-05-03.

- ^ a b "Zimbabwe Country Profile". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019-08-29. Retrieved 2020-05-04.

- ^ Kwan, Candice K.; Ernst, Joel D. (April 2011). "HIV and Tuberculosis: a Deadly Human Syndemic". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 24 (2): 351–376. doi:10.1128/CMR.00042-10. ISSN 0893-8512. PMC 3122491. PMID 21482729.

- ^ a b c d "HIV and AIDS in Zimbabwe". Avert. 2015-07-21. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- ^ Tlhajoane, Malebogo; Masoka, Tidings; Mpandaguta, Edith; Rhead, Rebecca; Church, Kathryn; Wringe, Alison; Kadzura, Noah; Arinaminpathy, Nimalan; Nyamukapa, Constance; Schur, Nadine; Mugurungi, Owen (2018-09-21). "A longitudinal review of national HIV policy and progress made in health facility implementation in Eastern Zimbabwe". Health Research Policy and Systems. 16 (1): 92. doi:10.1186/s12961-018-0358-1. ISSN 1478-4505. PMC 6150955. PMID 30241489.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b "Zimbabwe". United States Department of State. Retrieved 2020-03-27.

- ^ "A comparative analysis of national HIV policies in six African countries with generalized epidemics". WHO. Retrieved 2020-03-27.

- ^ "2018 Progress reports submitted by countries". UNAIDS. Retrieved 2020-03-27.

- ^ a b "World Report 2020: Rights Trends in Zimbabwe". Human Rights Watch. 2020-01-07. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- ^ "History | Zimbabwe | U.S. Agency for International Development". www.usaid.gov. 2020-02-05. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- ^ "Global Health | Zimbabwe | U.S. Agency for International Development". www.usaid.gov. 2020-02-05. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- ^ "UNAIDS data 2019". www.unaids.org. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- ^ a b McCarthy, Elizabeth; Joseph, Jessica; Foster, Geoff; Mangwiro, Alexio-Zambezio; Mwapasa, Victor; Oyeledun, Bolanle; Phiri, Sam; Sam-Agudu, Nadia A.; Essajee, Shaffiq (2017-06-01). "Modeling the Impact of Retention Interventions on Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV: Results From INSPIRE Studies in Malawi, Nigeria, and Zimbabwe". Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999). 75 (2): S233–S239. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000001364. ISSN 1525-4135. PMC 5432093. PMID 28498194.

- ^ Mtetwa, Sibongile; Busza, Joanna; Chidiya, Samson; Mungofa, Stanley; Cowan, Frances (2013-07-31). ""You are wasting our drugs": health service barriers to HIV treatment for sex workers in Zimbabwe". BMC Public Health. 13 (1): 698. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-698. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC 3750331. PMID 23898942.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Tsang, Eileen Yuk-ha; Qiao, Shan; Wilkinson, Jeffrey S.; Fung, Annis Lai-chu; Lipeleke, Freddy; Li, Xiaoming (2019-01-28). "Multilayered Stigma and Vulnerabilities for HIV Infection and Transmission: A Qualitative Study on Male Sex Workers in Zimbabwe". American Journal of Men's Health. 13 (1): 155798831882388. doi:10.1177/1557988318823883. ISSN 1557-9883. PMC 6440054. PMID 30819062.

- ^ "HIV/AIDS". Gays and Lesbians of Zimbabwe. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- ^ "World Report 2019: Rights Trends in Zimbabwe". Human Rights Watch. 2018-12-19. Retrieved 2020-04-03.

- ^ Hunt, Jennifer; Bristowe, Katherine; Chidyamatare, Sybille; Harding, Richard (2017-04-01). "'They will be afraid to touch you': LGBTI people and sex workers' experiences of accessing healthcare in Zimbabwe—an in-depth qualitative study". BMJ Global Health. 2 (2): e000168. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000168. ISSN 2059-7908. PMC 5435254. PMID 28589012.