Dreamland (Coney Island, 1904)

Seen in 1907 | |

| Location | Coney Island, Brooklyn, New York, United States |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°34′37″N 73°58′44″W / 40.577°N 73.979°W |

| Status | Defunct |

| Opened | May 15, 1904 |

| Closed | May 27, 1911 |

| Owner | William H. Reynolds |

Dreamland was an amusement park at Coney Island, Brooklyn, New York City, which operated from 1904 to 1911. It was the last of the three original large parks built on Coney Island, along with Steeplechase Park and Luna Park.[1]

Creation

The park was founded by William H. Reynolds, a former state senator and successful Brooklyn real estate developer.[2][3][4] He designed the park to compete with Luna Park, a neighboring amusement park opened in 1903. Dreamland was supposed to be refined and elegant in its design and architecture, compared to Luna Park with its many rides and chaotic noise.[5]

Reynolds purchased a 15-acre (6.1 ha) parcel at Surf Avenue and West Eighth Street on which to build the park, using proxy buyers in order to hide his real ambitions for the lot. Once he bought the site, he used political power to demolish West Eighth Street in order to expand the lot. Today, the site is near the West Eighth Street subway station opposite Culver Depot, the then-terminal of New York City Subway's BMT Brighton Line and BMT Culver Line. Culver Depot itself later became the site of the New York Aquarium and the adjacent subway station.[5]

Operation

Opened on May 15, 1904, Dreamland was a park in which everything was reputed to be bigger and more expansive than in neighboring Luna Park.[2] Dreamland had a larger central "Tower" and one million electric light bulbs illuminating and outlining its buildings,[5][6] four times as many lights as Luna Park.[5] Dreamland featured relatively high-class entertainment and dramatic spectacles based on morality themes such as "The End of the World" and the Orient Theater's "Feast of Beshazzar and the Destruction of Babylon."[7] It also featured elegant architecture, pristine white towers, and some educational exhibits along with the rides and thrills.

Among Dreamland's attractions were a railway called Coasting Through Switzerland that ran through a Swiss alpine landscape; imitation Venetian canals with gondolas; a human zoo called the "Lilliputian Village" with three hundred dwarf inhabitants; a Filipino village featuring Igorot people in native dress, although many of the Filipinos were not Igorot and few Filipinos dressed this way by 1911; and a demonstration of firefighting in which two thousand people pretended to put out a blazing six-story building fire every half-hour.[5] However, many rides were imitations of Luna Park's. There were also two Shoot-the-Chutes with two ramps that could handle 7,000 hourly riders and a simulated submarine ride. The side shows were owned by the Dicker family, who also owned the hotel next to the park. There was also a display of baby incubators, where premature babies, triplets who were members of the Dicker family, were cared for and exhibited. The doctors advised them of the new invention, but they could not use it because incubators were not approved for use in hospitals, so the triplets were placed in the side show, which was allowed. Two survived and lived on to have full lives.[5]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

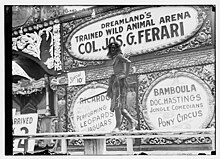

In a bid for publicity, the park put famous Broadway actress Marie Dressler in charge of the peanut-and-popcorn stands, with young boys dressed as imps in red flannel acting as salesmen. Dressler was said to be in love with Dreamland's dashing, handlebar-mustachioed, one-armed lion tamer who went by the name of Captain Jack Bonavita.[6] Bonavita, who commanded lions in the Bostock animal arena, had one arm amputated when his hand was severely clawed by one of the lions, and a blood infection spread through that hand.[5]

Destruction

In spite of its many draws, Dreamland struggled to compete with Luna Park, which was better managed.[5] In preparation for its 1911 season, many changes were made. Samuel W. Gumpertz (later director of the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus) was put in the park's top executive post. The buildings, once all painted white in a bid for elegance, were redone in bright colors. On the night before opening day, an attraction called Hell Gate, in which visitors took a boat ride on rushing waters through dim caverns, was undergoing last-minute repairs by a roofing company owned by Samuel Engelstein. A leak had to be caulked with tar. During these repairs, at about 1:30 a.m. on May 27, 1911, the light bulbs that illuminated the operations exploded, likely due to an electrical malfunction. In the darkness, a worker kicked over a bucket of hot pitch, and soon Hell Gate was in flames.[5]

The fire quickly spread throughout the park. The buildings were made of frames of lath (thin strips of wood) covered with staff (a moldable mixture of plaster of Paris and hemp fiber). Both materials were highly flammable, and as they were common in the Coney Island amusement parks, fires were a persistent problem there. Because of this, a new high-pressure water pumping station had been constructed at Twelfth Street and Neptune Avenue a few years earlier, but on that night it failed. Water was available, but there was not enough to contain the fire that enveloped Dreamland. The Dicker family's adjacent hotel also burned down in this fire.[5]

Chaos broke loose as the park burned. As the single-armed Captain Bonavita strove to save his big cats with only the swiftly encroaching flames for illumination, some of the terrified animals escaped, but about 60 animals died. A lion named Black Prince rushed into the streets, among crowds of onlookers, and was shot by police. By morning, the fire was out and Dreamland was completely destroyed and never rebuilt.[5] Early editions of The New York Times claimed the incubator babies had perished in the flames, but later the paper corrected this and reported that they had all been saved. According to contemporaneous accounts, a number of these saves were accomplished by Sgt. Frederick Klinck of the NYPD, who made several trips into the burning structure to rescue incubator babies.[5]

Almost ten years after the fire, Reynolds, who by then owned the majority of Dreamland's outstanding bonds and stood to make a windfall, used his political connections to have New York City purchase the land on which Dreamland once stood.[2] The city bought the area, valued at $1.5 million, for $1.8 million.[5]

In popular culture

Art

- Artist Philomena Marano created a body of work inspired by the park in the papier collé method, American Dream-Land.[9][10]

Film

- A fictionalized Dreamland serves as a major setting in Disney's 2019 live-action adaptation of Dumbo. The film references the electrical fire, but is not historically accurate to the actual events: in Dumbo, the fire took place in 1919, and Dreamland was owned by V. A. Vandevere, a fictional character.

Literature

- Kevin Baker wrote a historical novel, Dreamland, about life in New York City at the time Dreamland existed, touching on the politics, economics, social conditions of the time, and Dreamland is one of the central places in the book. His book also contains a description of the fire.

- Dutch writer J. Bernlef's novel De witte stad (The White City) narrates about the fictional lives of many Dreamland inhabitants.

- Dutch writer Arthur Japin's novel De grote wereld (The Big World), about two midgets, is partly set in Dreamland.

- Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas writes at length on Dreamland in his retroactive manifesto for Manhattan, Delirious New York.

- Dutch writer Peter Verhelst's novel Geschiedenis van een berg (History of a mountain) about a park based on Dreamland, called 'Droomland' (Dreamland).

- Henry Miller mentions Dreamland in his novel, Tropic of Capricorn: I was walking again in Dreamland and a man was walking above me on a tightrope and above him a man was sitting in an airplane spelling letters of smoke in the sky.

- Steven Millhauser, in his short story "Paradise Park", also talks about Dreamland as a rival amusement park. There are some similarities between Paradise Park and Dreamland.

- Fannie Flagg, in "Standing in the Rainbow", referred to Dreamland as being 'so big they had an entire little town there'.

- American author Alice Hoffman writes about Dreamland in her 2014 novel of historical fiction entitled "The Museum of Extraordinary Things." The book is set in New York City in the early 1900s and includes the Dreamland fire in the plot, as well as the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire.

- American author Christopher Bram sets the last part of his novel at Dreamland, in his 2000 novel of historical fiction entitled "The Notorious Dr. August: His Real Life and Crimes." The major character of the novel is conceived as one of the major "acts" at Dreamland in an extensive treatment of the setting.

Music

- Tom Waits wrote the song "Tabletop Joe" in which the title character is himself part of the freak show exhibit, "a man without a body," but Joe becomes rich and famous as a part of the Dreamland show, and after being shunned, after joining Dreamland, he now feels that he is where he belongs.

- Brian Carpenter wrote a play treatment which he used as a springboard for lyrics and compositions behind his second studio album for Beat Circus entitled Dreamland. Carpenter's Dreamland is a 150-page score and song cycle interwoven with Carpenter's fictional tale of an impoverished, alcoholic gold miner who makes a pact with the devil before fleeing eastward to work in Dreamland's sideshows. The album featured Todd Robbins, alumnus of Coney Island, and its booklet includes historical images of Dreamland donated by the Coney Island Museum.[11]

Podcasts

- The August 28, 2019 episode of "The Memory Palace" by Nate DiMeo is dedicated to Dreamland.

See also

References

- ^ David Goldfield, Encyclopedia of American Urban History, SAGE Publications – 2006, page 185

- ^ a b c David A. Sullivan. "Dreamland (1904–1911)". heartofconeyisland.com. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ^ Ultimate Rollercoaster, LLC (1996–2012). "Roller Coaster History: Early 1900s: Coney Island". rollercoaster.com. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ "Walkabout: William H. Reynolds, conclusion". Brownstoner.com. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "At Hell's Gate: The Rise and Fall of Coney Island's Dreamland". Entertainment Designer. February 4, 2012. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ a b Edo McCullough (1957). Good Old Coney Island: A Sentimental Journey Into the Past – the Most Rambunctious, Scandalous, Rapscallion, Splendiferous, Pugnacious, Spectacular, Illustrious, Prodigious, Frolicsome Island on Earth. Fordham University Press. p. 198. ISBN 9780823219971.

- ^ pbs.org The American Experience, People & Events Luna Park Opens

- ^ Michael Immerso, Coney Island: The People's Playground, Rutgers University Press, 2002, page 73

- ^ Denson, Charles, "Coney Island Lost and Found," Ten Speed Press, 2002, pages 227–231

- ^ Breuckelen Magazine Video "Interview with Philomena Marano" June 2014

- ^ Webster, Sarah (February 1, 2008). "Circus Coming To Town". Asbury Park Press. Retrieved February 2, 2008.

External links

- Dreamland at amusement-parks.com

- Maps and postcards of Dreamland

- Dreamland Park History

- Dreamland and William Reynolds at Heart of Coney Island

- Panoramic photo, "Destruction of Dreamland", 1911, from the Library of Congress