Asmara Moerni

| Asmara Moerni | |

|---|---|

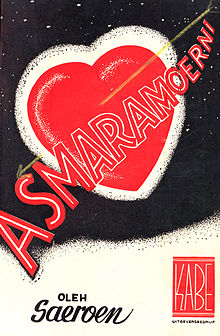

Cover of the novelisation | |

| Directed by | Rd Ariffien |

| Screenplay by | Saeroen |

| Produced by | Ang Hock Liem |

| Starring |

|

Production company | |

Release date |

|

| Country | Dutch East Indies |

| Language | Indonesian |

Asmara Moerni ([asˈmara mʊrˈni]; Perfected Spelling: Asmara Murni; Indonesian for True Love) is a 1941 romance film from the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) directed by Rd Ariffien and produced by Ang Hock Liem for Union Films. Written by Saeroen, the film followed a doctor who falls in love with his maid, as well as her failed romance with a fellow villager. Starring Adnan Kapau Gani, Djoewariah, and S. Joesoef, the black-and-white film was cast and advertised to cater to the growing native intelligentsia. Despite mixed reviews, it was a commercial success. As with most films of the Indies, Asmara Moerni may be lost.

Plot

After four years of doing his residency in Singkawang, Borneo, Dr. Pardi (Adnan Kapau Gani) returns to Java to open a practice. Before then, he goes to Cigading to visit his family and give them souvenirs. Upon arrival he is stunned to find that his family's maid Tati (Djoewariah), who had been his childhood playmate, is now a grown and beautiful woman. He secretly begins to fawn over Tati, although he does not tell her the reason. When Pardi's mother tells him he should marry quickly, he refuses all of her suggested brides. He says only that he already has someone in mind, aware that his mother would never approve an inter-class marriage with the maid.

Tati's fiancé, Amir (S. Joesoef), is jealous of all the attention that Tati is receiving, which leaves her no time for him. He plans to leave Cigading for the capital, Batavia (today Jakarta), where he will find work. Tati, upon learning this, joins him. She lives at her aunt's home in the city, making a living by washing clothes, while he finds lodging with a local man and learns to drive a becak (pedicab). Together they begin saving for their wedding. Unknown to them, Pardi has cut short his time in Cigading to move to Batavia, both to begin his new job and to find Tati.

Days before the wedding, Amir is playing his flute when he is approached by a singer known as Miss Omi, who asks him to join her troupe on an international tour. Amir refuses, even after Omi hires him to drive her around the city in an attempt to convince him. After dropping Omi off, Amir is approached by a man who asks him to deliver a package; however, before he can deliver the package Amir is arrested and charged with smuggling opium.

When Amir does not return, Tati and her aunt are worried: as Tati saw Amir with Omi, she fears that the two have run away together. Heartbroken, she intends to return to Cigading. When she and her aunt visit their boss, Abdul Sidik, they unknowingly pass Pardi – Abdul Sidik's doctor. Upon returning home, Pardi calls Abdul Sidik and asks him to take Tati in as if she were his daughter and educate her. Tati is a fast learner, and is soon comparable to any woman from a wealthy family.

After being held eighteen months without trial, Amir is released and returned to Batavia. He is unable to find Tati, leaving him to wander the streets. Omi spots him, and again she asks him to play with her troupe. Amir agrees, and soon newspapers are filled with advertisements touting his name. Spotting one, Tati and Abdul Sidik go to a performance, only to learn that Amir was the victim of a car accident. At the hospital, where Amir is being treated by Pardi, Tati learns the truth behind Amir's absence. On his deathbed, Amir asks Pardi to take care of Tati; the two are later married.[a]

Production

Asmara Moerni was directed by Rd Ariffien, a former journalist who had been active in the nationalist and labour movements before turning to theatre.[1] He had joined Union Films – the company behind Asmara Moerni – in 1940, making his debut with Harta Berdarah (Bloody Treasure).[2] Union's head Ang Hock Liem produced,[3] while the story was written by journalist Saeroen,[4] who had joined Union after commercial success on Albert Balink's Terang Boelan (Full Moon, 1937) and with the production house Tan's Film.[5]

The black-and-white film starred Adnan Kapau Gani, Djoewariah, and S. Joesoef.[6] It was the feature film debut of Gani and Joesoef,[7] while Djoewariah had been on Union's payroll since Bajar dengan Djiwa (Pay with Your Soul) the preceding year.[8]

At the time there was a growing movement to attract native intelligentsia, educated at schools run by the Dutch colonial government, and convince them to view domestic films, which were generally considered to be of much lower quality than imported Hollywood productions.[9] This was blamed, in part, on the dominance of theatrically trained actors and crew.[b] As such, Ariffien invited Gani, at the time a medical doctor and a prominent member of the nationalist movement, to join the cast. Although some nationalists considered Gani's involvement in Asmara Moerni as besmirching the independence movement, Gani considered it necessary: he believed audiences needed to have higher opinions of domestic film productions.[10]

Release and reception

Asmara Moerni was premiered on 29 April 1941 at Orion Theatre in Batavia; the crowds were mostly natives and ethnic Chinese.[11] Rated for all ages, advertising for the film emphasised Gani's education and Joesoef's upper-class background.[12] It was also advertised as breaking away from the conventional standards of stage theatre, such as music, which were omnipresent in the contemporary film industry.[12] By August 1941 it was screened in Singapore, then part of the Straits Settlements, and billed as a "modern Malay drama".[13] A novelisation was published later in 1941 by the Yogyakarta-based Kolff-Buning.[14]

The film was a commercial success,[10] though reviews were mixed. An anonymous review for the Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad found the film "fascinating",[c] with good acting,[11] though another review for the same paper found that, though the film was better than contemporary works such as Pantjawarna and Sorga Ka Toedjoe, its claim to abandon stage standards was to be taken "with a pinch of salt".[d][15] A review from the Surabaya-based Soerabaijasch Handelsblad found the film full of drama, describing it as "Western motifs, played in the native environment, with a specifically Sundanese situation".[e][4]

Legacy

After Asmara Moerni, Union produced a further three films;[16] only one, Wanita dan Satria, was by Rd Ariffien, who left the company soon after,[17] as did Saeroen.[18] Gani did not act in any further films,[10] but instead returned to the nationalist movement. During the Indonesian National Revolution (1945–49) he became known as a smuggler, and after independence became a government minister.[19] In November 2007 Gani was made a National Hero of Indonesia.[20] Djoewariah continued to act until the 1950s, when she migrated to theatre after receiving a series of increasingly minor roles.[8]

Asmara Moerni was screened as late as November 1945.[21] The film is likely lost. Throughout the world, all movies were then shot on highly flammable nitrate film, and after a fire destroyed much of Produksi Film Negara's warehouse in 1952, many films shot on nitrate were deliberately destroyed.[22] As such, American visual anthropologist Karl G. Heider suggests that all Indonesian films from before 1950 are lost.[23] However, JB Kristanto's Katalog Film Indonesia (Indonesian Film Catalogue) records several as having survived at Sinematek Indonesia's archives, and film historian Misbach Yusa Biran writes that several Japanese propaganda films have survived at the Netherlands Government Information Service.[24]

See also

Explanatory notes

- ^ Derived from the novelisation published by Kolff-Buning.

- ^ This included Roekiah, Kartolo, Fifi Young, Astaman, Ratna Asmara, and Andjar Asmara. See Biran (2009, p. 204).

- ^ Original: "... boeiend ..."

- ^ Original: "... moet men dit wel met een korreltje zout"

- ^ Original: "... een geheel naar westersche motieven opgezet scenario, spelend in het inheemsche milieu met specifiek Soendaneesche decors."

References

- ^ Biran 2009, p. 232.

- ^ Filmindonesia.or.id, Rd Ariffien.

- ^ Filmindonesia.or.id, Asmara Moerni.

- ^ a b Soerabaijasch Handelsblad 1941, Sampoerna: 'Asmara Moerni'.

- ^ Filmindonesia.or.id, Saeroen.

- ^ Filmindonesia.or.id, Asmara Moerni; Soerabaijasch Handelsblad 1941, (untitled)

- ^ Biran 2009, pp. 262–63; Soerabaijasch Handelsblad 1941, (untitled)

- ^ a b Filmindonesia.or.id, Djuariah.

- ^ Biran 2009, p. 260.

- ^ a b c Biran 2009, pp. 262–63.

- ^ a b Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad 1941, Filmaankondigingen.

- ^ a b Soerabaijasch Handelsblad 1941, (untitled).

- ^ The Straits Times 1941, (untitled).

- ^ Saeroen 1941, p. 1.

- ^ Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad 1941, Iets over de Maleische Film.

- ^ Biran 2009, p. 233.

- ^ Biran 2009, p. 263.

- ^ Biran 2009, p. 234.

- ^ Mufid 2012, Menyelundup untuk Kemakmuran Republik.

- ^ Suara Merdeka 2007, Presiden Anugerahkan Gelar.

- ^ Soeara Merdeka 1945, Pilem.

- ^ Biran 2012, p. 291.

- ^ Heider 1991, p. 14.

- ^ Biran 2009, p. 351.

Works cited

- "Asmara Moerni". filmindonesia.or.id (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Konfiden Foundation. Archived from the original on 26 July 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- Biran, Misbach Yusa (2009). Sejarah Film 1900–1950: Bikin Film di Jawa [History of Film 1900–1950: Making Films in Java] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Komunitas Bamboo working with the Jakarta Art Council. ISBN 978-979-3731-58-2.

- Biran, Misbach Yusa (2012). "Film di Masa Kolonial" [Film in the Colonial Period]. Indonesia dalam Arus Sejarah: Masa Pergerakan Kebangsaan [Indonesia in the Flow of Time: The Nationalist Movement] (in Indonesian). Vol. V. Ministry of Education and Culture. pp. 268–93. ISBN 978-979-9226-97-6.

- "Djuariah, Ng. R". filmindonesia.or.id (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Konfiden Foundation. Archived from the original on 20 July 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- "Filmaankondigingen Orion: 'Asmara Moerni'" [Orion Film Announcements: 'Asmara Moerni']. Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad (in Dutch). Batavia: Kolff & Co. 1 May 1941. p. 11.

- Heider, Karl G (1991). Indonesian Cinema: National Culture on Screen. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1367-3.

- "Iets over de Maleische Film" [Thoughts on Malay Films]. Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad (in Dutch). Batavia: Kolff & Co. 8 May 1941. p. 10.

- Mufid, Fauzani (23 July 2012). "Menyelundup untuk Kemakmuran Republik" [Smuggling for the Good of the Republic]. Prioritas (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- "Pilem" [Films]. Soeara Merdeka (in Indonesian). Semarang. 7 November 1945. p. 4. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014.

- "Presiden Anugerahkan Gelar Pahlawan Nasional" [President Awards National Hero Titles]. Suara Merdeka (in Indonesian). 10 November 2007. Archived from the original on 3 February 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- "Rd Ariffien". filmindonesia.or.id (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Konfiden Foundation. Archived from the original on 30 September 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- Saeroen (1941). Asmara Moerni [True Love] (in Indonesian). Yogyakarta: Kolff-Buning. OCLC 29049476. (book acquired from the collection of Museum Tamansiswa Dewantara Kirti Griya, Yogyakarta)

- "Saeroen". filmindonesia.or.id (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Konfiden Foundation. Archived from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- "Sampoerna: 'Asmara Moerni'". Soerabaijasch Handelsblad (in Dutch). Surabaya: Kolff & Co. 27 June 1941. p. 6.

- "(untitled)". Soerabaijasch Handelsblad (in Dutch). Surabaya: Kolff & Co. 24 June 1941. p. 4.

- "(untitled)". The Straits Times. Singapore. 29 August 1941. p. 6.