Gabaculine

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

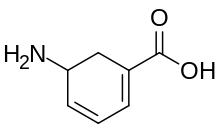

5-Aminocyclohexa-1,3-diene-1-carboxylic acid

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C7H9NO2 | |

| Molar mass | 139.154 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Gabaculine is a naturally occurring neurotoxin first isolated from the bacteria Streptomyces toyacaensis,[1] which acts as a potent and irreversible GABA transaminase inhibitor,[2][3] and also a GABA reuptake inhibitor.[4][5] Gabaculine is also known as 3-amino-2,3-dihydrobenzoic acid hydrochloride [6] and 5-amino cyclohexa-1,3 dienyl carboxylic acid.[7] Gabaculine increased GABA levels in the brain and had an effect on convulsivity in mice.[7]

Mechanism of action

Gabaculine includes a comparable structure to GABA and a dihydrobenzene ring. This comparable GABA structure is used in order to be able to take the place of GABA during the first steps of transamination, including transaldimination and 1,3-prototrophic shift to the pyridoxamine imine.[8] Following this, a proton from the dihydrobenzene ring is abstracted by an enzymatic base, thus causing the ring to become aromatic.[8] The aromatic stabilization energy of the aromatic ring is what causes this reaction to be irreversible, thus causing the complex not to react further.[8]

Preclinical studies

Animal studies to determine the effect of gabaculine on GABA levels in the brain were heavily conducted around the 1970s.[9] These in vivo studies involved mostly the use of mice that underwent intravenous administration of this drug. Each of these studies concluded that gabaculine has a great potential to increase the GABA levels in the brain of these mice in a time dependent manner.[7] Along with determining the effect of GABA levels, in vivo studies were conducted to investigate the ability of gabaculine to inhibit convulsions in mice. Results indicated that gabaculine provided a clear anticonvulsant effect against seizures induced by high doses of chemoconvulsants or electroshock.[10] The toxicity of this compound was also investigated using animal mouse models. This study showed that at anticonvulsant doses, gabaculine is extremely potent and toxic when compared to other GABA transaminase inhibitors, with an ED50 of 35 mg/kg and LD50 of 86 mg/kg.[10] Because of this potential lethal effect, gabaculine was proved to be too toxic for use as a drug however,[8] it can still be used as a compound to alter GABA levels in studies of experimental epilepsy.[10]

Regulation

Gabaculine has not been approved by the FDA as a pharmaceutical entity; however, it can be used as a chemical compound for research purposes only.[11] This compound is not considered a hazardous substance according to OSHA 29 CFR 1910.1200.[6]

References

- ^ Kobayashi K, Miyazawa S, Endo A (April 1977). "Isolation and inhibitory activity of gabaculine, a new potent inhibitor of gamma-aminobutyrate aminotransferase produced by a Streptomyces". FEBS Letters. 76 (2): 207–10. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(77)80153-1. PMID 862902.

- ^ Rando RR (October 1977). "Mechanism of the irreversible inhibition of gamma-aminobutyric acid-alpha-ketoglutaric acid transaminase by the neurotoxin gabaculine". Biochemistry. 16 (21): 4604–10. doi:10.1021/bi00640a012. PMID 410442.

- ^ Irifune M, Katayama S, Takarada T, et al. (December 2007). "MK-801 enhances gabaculine-induced loss of the righting reflex in mice, but not immobility". Can J Anaesth. 54 (12): 998–1005. doi:10.1007/BF03016634. PMID 18056209.

- ^ Allan RD, Johnston GAR, Twitchin B. Effects of Gabaculine on uptake, binding and metabolism of GABA. Neuroscience Letters. 1977;4:51-54.

- ^ Høg S, Greenwood JR, Madsen KB, Larsson OM, Frølund B, Schousboe A, Krogsgaard-Larsen P, Clausen RP (2006). "Structure-activity relationships of selective GABA uptake inhibitors". Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 6 (17): 1861–82. doi:10.2174/156802606778249801. PMID 17017962. Archived from the original on 2013-04-14.

- ^ a b Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. "Gabaculine Material Safety Data Sheet". Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ^ a b c Mutsui, Yoshiki; Deguchi, Takehiko (1977). "Effects of gabaculine, a new potent inhibitor of gamma-aminobutyrate transaminase, on brain gamma-aminobutyrate content and convulsions in mice". Life Sciences. 20 (7): 1291–1296. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(77)90505-7. PMID 850479.

- ^ a b c d Frey, Perry; Ables, Robert; Hegeman, Adrian (Dec 29, 2006). Enzymatic Reaction Mechanism. New York: Oxford University Press Inc. pp. 262–263. ISBN 0195122585. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ^ Rando, Robert; Bangerter, F.W. (May 13, 1977). "The In Vivo Inhibition of GABA-transaminase by Gabaculine". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 76 (4): 1276–1281. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(77)90993-7. PMID 901477.

- ^ a b c Loscher, Wolfgang (1980). "A Comparative Study of the Pharmacology of lnhibitors of GABA-Metabolism". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 315 (2): 119–128. doi:10.1007/BF00499254. PMID 6782493. S2CID 26483388.

- ^ PubChem. "Gabaculine". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 9 December 2014.