Hurricane Hector (2018)

| Category 4 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

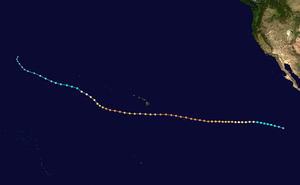

Hurricane Hector at peak intensity southeast of Hawaii on August 6 | |

| Formed | July 31, 2018 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | August 16, 2018 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 155 mph (250 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 936 mbar (hPa); 27.64 inHg |

| Fatalities | None |

| Damage | Minimal |

| Areas affected | Hawaii, Johnston Atoll |

| Part of the 2018 Pacific hurricane and typhoon seasons | |

Hurricane Hector was a powerful and long-lasting tropical cyclone that traversed the Pacific Ocean during late July and August 2018. Hector was the eighth named storm, fourth hurricane, and third major hurricane[nb 1] of the 2018 Pacific hurricane season.[2] It originated from a disturbance[nb 2] that was located north of South America on July 22. The disturbance tracked westward and entered the eastern Pacific around July 25. It gradually organized over the next several days, becoming a tropical depression at 12:00 UTC on July 31. The system was upgraded into a tropical storm about 12 hours later and received the name Hector. Throughout most of its existence, the cyclone traveled due west or slightly north of west. A favorable environment allowed the fledgling tropical storm to rapidly intensify to its initial peak as a Category 2 hurricane by 18:00 UTC on August 2. Wind shear caused Hector to weaken for a brief period before the storm began to strengthen again. Hector reached Category 3 status by 00:00 UTC on August 4 and went through an eyewall replacement cycle soon after, which caused the intensification to halt. After the replacement cycle, the cyclone continued to organize, developing a well-defined eye surrounded by cold cloud tops.

Hector crossed the 140th meridian west, entering the central Pacific Ocean early on August 6 as a Category 4 hurricane. It reached its peak intensity around 18:00 UTC that day, with winds of 155 mph (250 km/h) and a pressure of 936 mbar (27.64 inHg). Hector's intensity fluctuated between Category 3 and Category 4 over the next several days as a result of eyewall replacement cycles and changing environmental conditions. The hurricane passed south of Hawaii's Big Island on August 8. Strong wind shear caused Hector to weaken rapidly and take on a more northwestward track after August 11. It fell below major hurricane intensity around 18:00 UTC on August 11. Hector had spent 186 hours at that intensity – longer than any other hurricane on record in the eastern Pacific basin. The structure of the storm rapidly deteriorated as Hector approached the International Date Line; it weakened into a tropical storm by 00:00 UTC on August 13. Hector crossed into the western Pacific Ocean during the middle of the day. The tropical storm then moved generally westward while continuing to decay. It weakened into a tropical depression by midnight UTC on August 15 and dissipated the next day around 18:00 UTC.

The impact on land from the storm was minimal. Hector did not make landfall, but as it approached Hawaii, tropical storm watches and warnings were issued for the Big Island, as well as tropical storm watches for the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Hector caused high surf as it passed by to the south of the main islands, necessitating the rescue of several dozen people on Oahu.

Origins, development, and initial peak

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

Hurricane Hector's origins can be traced to a low-latitude disturbance that was located north of French Guiana and Suriname around July 22. The disturbance's path prior to that time is uncertain: thunderstorm activity was subdued across the tropical Atlantic due to the presence of dry Saharan air, and the Intertropical Convergence Zone dipped southward and exhibited no fluctuations; this combination of events made it impossible to trace the disturbance to a particular tropical wave. Hector's precursor began producing convection while traveling westward over northern South America, entering the Eastern Pacific basin by July 25. A low-pressure trough formed on the next day south of Central America and southern Mexico.[4] The National Hurricane Center (NHC) first mentioned the possibility of tropical development on July 26.[5] Located within a favorable environment fueled by a kelvin wave and the Madden–Julian oscillation,[4] the disturbance gradually became more organized over the next five days as it continued generally westward.[6] The system developed into Tropical Depression Ten-E around 12:00 UTC on July 31 while about 805 mi (1,295 km) south-southwest of the southern tip of the Baja California Peninsula.[4] At that time, the system was travelling west-northwest under the influence of a deep-layer ridge to its north. Initially, the depression was irregularly shaped and its circulation elongated,[7] but it steadily improved in organization over the next 12 hours, becoming Tropical Storm Hector at 00:00 UTC on August 1.[4][8]

After strengthening into a tropical storm, Hector remained disorganized for several hours as a result of increasing easterly wind shear, with most of its convection displaced to the south and west.[9] Warm sea surface temperatures of 81–82 °F (27–28 °C) allowed Hector to begin a 30-hour period of rapid intensification at 12:00 UTC.[4] Around that time, the low- and mid-level centers were becoming more aligned and curved banding features were increasing. The system also turned westward as the aforementioned ridge built to the north of Hector.[10][11] Over the next several hours, Hector significantly improved in organization, with its low-level center becoming markedly embedded within the deep convection and the development of a mid-level eye.[12] Hector intensified into a Category 1 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson scale around 12:00 UTC, developing a small eye on satellite imagery.[4][13] Six hours later, the storm reached its initial peak intensity as a Category 2 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 105 mph (165 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 975 mbar (28.79 inHg).[4] Shortly thereafter, Hector began weakening, with its eye becoming cloud-filled and the northern eyewall eroding due to northerly shear.[14][4] Hector's structure continued to degrade over the next several hours with the eye becoming nearly indistinguishable from its surroundings and the formation of a secondary concentric eyewall structure.[15] The storm bottomed out as a Category 1 hurricane at approximately 12:00 UTC on August 3 as it continued to travel due west.[4]

Strengthening and peak intensity

Hector began to strengthen a short time later as it traversed an area of slightly cooler sea temperatures, low wind shear, and elevated mid-level moisture. The storm's eye cleared out on satellite imagery as convection intensified in the eyewall.[16] Hector became a Category 3 major hurricane around 00:00 UTC on August 4, while located approximately 1,680 mi (2,705 km) west-southwest of the southern tip of Baja California.[4] Later in the day, the system began to undergo an eyewall replacement cycle.[17] Six hours later, around 18:00 UTC, the eyewall cycle had completed, with only one eyewall remaining. At that time, the cyclone was also beginning to acquire some annular characteristics.[18] The hurricane's structure began to decay on August 5, with the eye becoming less distinct by 12:00 UTC. Meanwhile, microwave imagery showed two concentric eyewalls, indicating that Hector was entering a second eyewall replacement cycle.[19] Hector became a Category 4 hurricane at 18:00 UTC after completing the eyewall cycle.[4] The hurricane exhibited a symmetric central dense overcast with few banding features elsewhere, a characteristic of an annular tropical cyclone.[20]

Hector began to move slightly north of west due to a weakness in a subtropical ridge located to the northeast of the Hawaiian Islands. The hurricane crossed the 140th meridian west shortly after 06:00 UTC on August 6, entering the Central Pacific Hurricane Center's (CPHC) area of responsibility.[4] At that time, Hector possessed a distinct eye surrounded by −94 to −112 °F (−70 to −80 °C) clouds.[21] About six hours later, a 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron plane recorded a stepped frequency microwave radiometer (SFMR) wind speed of 158 mph (254 km/h) as it surveyed the cyclone. Hector reached its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 155 mph (250 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 936 mbar (27.64 inHg) around 18:00 UTC.[4] The storm turned towards the west-northwest shortly after as the ridge continued to weaken.[22] The hurricane maintained peak intensity for about six hours before beginning to weaken as it entered an area of mid-level dry air. Despite slightly degrading in structure, Hector still maintained a 12 mi (19 km) wide eye.[23]

Passage south of Hawaii and secondary peak

As Hector approached Hawaii, its weakening trend continued due to mid-level dry air, low ocean heat content, and 81 °F (27 °C) sea surface temperatures.[4][24] The hurricane's eye shrank and became nearly indistinguishable from surrounding clouds on satellite imagery as the system tracked westward.[24][25] Hector weakened into a low-end Category 3 hurricane as it passed about 230 mi (370 km) south of the Big Island on August 8. WSR-88D radar from Hawaii as well as microwave and satellite imagery showed Hector was undergoing a third eyewall replacement cycle during that time.[4]

Hurricane Hector warranted the issuance of tropical storm watches and warnings from August 6–8 as it passed near the Big Island, as well as tropical storm watches for Johnston Atoll and various islands in the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument from August 9–13. Although forecasts depicted Hector remaining south of Hawaii, concerns were raised over the safety of residents displaced by the ongoing eruption of Kīlauea, many of whom were in temporary tent structures that could not withstand a hurricane. Plans were made to relocate people to sturdier structures.[26] Overall, the impact to Hawaii was minimal; peak 2-minute sustained winds of 25 mph (40 km/h) were recorded in South Point on the Big Island and 0.17 in (4.3 mm) of rain registered at Hilo International Airport.[4] The ports of Hilo and Kawaihae were closed on August 7 to inbound traffic as gale-force winds were expected to occur within the next 24 hours.[27] All Hawaiian ports resumed normal operations on August 10.[28] Also on August 8, the acting mayor of Hawaii County, Wil Okabe, declared a state of emergency.[29] As the hurricane passed south of the island on August 8, all absentee walk-in voting sites in Hawaii County were shut down. Whittington, Punaluu, and Milolii Beach Parks were also closed.[30] At the same time, surf was reported along the south-facing shores of the Big Island as 20 ft (6.1 m) high.[31] At least 90 people had to be rescued on Oahu due to dangerous swells generated by the cyclone.[32]

After passing by Hawaii, Hector began another period of strengthening on August 9 as it moved across a region of slightly warmer sea surface temperatures and higher ocean heat content.[4] The temperature of the hurricane's eye increased and the cloud tops of the eyewall cooled after the completion of the replacement cycle.[33][34] Hector reached its secondary peak as a Category 4 hurricane around 18:00 UTC on August 10 with 140 mph (220 km/h) winds. Around that time, the system had begun a west-northwest motion as it rounded the edge of a subtropical ridge that was located northeast.[4][35]

Weakening and demise

Hector began to weaken once more as an upper-level low located just east of the International Date Line imparted southerly shear and caused the cyclone to take on a more northwesterly track.[4] As a result, the storm's eye became cloud-filled on August 11.[36] Hector fell below major hurricane status around 18:00 UTC on August 11, the first time the hurricane had done so after spending a record 186 consecutive hours at that intensity.[4][37] By early August 12, the hurricane's eye had become invisible on satellite imagery and only a region of warmer cloud tops remained on infrared imagery.[38] Hector began to rapidly weaken soon after as wind shear increased further to 35 mph (55 km/h); the appearance of the cyclone quickly deteriorated as a result.[39] Later in the day, Hector's low-level center became displaced to the south of its thunderstorm activity as strong wind shear continued to bombard the system.[4][40] Hector weakened into a tropical storm around 00:00 UTC on August 13.[4] Convection associated with Hector began to dissipate on August 13, leaving the low-level center uncovered; all that remained were regions of cirrus clouds.[41] Hector crossed into the western Pacific Ocean shortly after 15:00 UTC on August 13 as a weakening tropical storm,[4] entering the Japan Meteorological Agency's (JMA) area of responsibility. Around that time, bursts of convection had formed northwest of the low-level center.[42] At the time Hector left the eastern Pacific basin, it had the highest accumulated cyclone energy of a Pacific hurricane since 1994's Hurricane John.[43]

Once Hector crossed the International Date Line, the JMA recognized it as a tropical storm with 45 mph (75 km/h) 10-minute sustained winds.[44] Meanwhile, the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) estimated that Hector had 1-minute sustained winds of 45 mph (75 km/h).[45] After entering the western Pacific, Hector tracked westward under the influence of a subtropical high.[46] The tropical storm's structure consisted of weak banding features and a low-level center partially covered by convection on August 14.[47] At the same time, Hector was located within an environment of dry air, low-to-moderate wind shear, and neutral 81 °F (27 °C) sea surface temperatures.[48][49] Around 06:00 UTC, the JTWC downgraded Hector to a tropical depression.[4] Convection continually decreased in organization throughout the day.[50] Hector restrengthened into a tropical storm around 18:00 UTC on August 14 with winds of 45 mph (75 km/h).[4] Meanwhile, the storm turned towards the west-northwest as it rounded the southern edge of the subtropical high.[51] At 00:00 UTC on August 15, the JMA downgraded Hector to a tropical depression.[52] At the same time, the JTWC indicated that Hector had transitioned into a subtropical storm with no change in intensity. The JTWC downgraded Hector to a subtropical depression around 12:00 UTC on August 15. The JTWC continued tracking Hector until 06:00 UTC on August 16,[4] while the JMA monitored the cyclone until 18:00 UTC of that day.[53]

See also

- Weather of 2018

- Tropical cyclones in 2018

- List of Category 4 Pacific hurricanes

- Other tropical cyclones with the same name

- List of Hawaii hurricanes

- Hurricane Dora (1999) – another hurricane that traversed all three North Pacific basins

- Hurricane Ioke (2006) – a storm that set similar longevity records

- Hurricane Lane (2018) – Category 5 hurricane that became Hawaii's wettest tropical cyclone on record

Notes

References

- ^ "Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Central Pacific Hurricane Center (April 26, 2024). "The Northeast and North Central Pacific hurricane database 1949–2023". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Archived from the original on May 29, 2024. A guide on how to read the database is available here.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Glossary of NHC Terms". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Berg, Robbie; Houston, Sam; Birchard, Thomas (1 July 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Hector (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ^ Avila, Lixion (26 July 2018). Tropical Weather Outlook [1100 AM PDT Thu Jul 26 2018] (Report). NHC Graphical Outlook Archive. National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ Stewart, Stacy (31 July 2018). Tropical Weather Outlook [500 AM PDT Tue Jul 31 2018] (Report). NHC Graphical Outlook Archive. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ^ Stewart, Stacy (31 July 2018). Tropical Depression Ten-E Discussion Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ^ Brown, Daniel (1 August 2019). Tropical Storm Hector Discussion Number 2 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ^ Zelinsky, David (1 August 2018). Tropical Storm Hector Discussion Number 3 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ^ Blake, Eric (1 August 2018). Tropical Storm Hector Discussion Number 5 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ^ Brown, Daniel (2 August 2018). Tropical Storm Hector Discussion Number 6 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ^ Zelinsky, David (2 August 2019). Tropical Storm Hector Discussion Number 7 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 5 August 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ^ Blake, Eric (2 August 2018). Hurricane Hector Discussion Number 8 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ Beven, Jack (3 August 2018). Hurricane Hector Discussion Number 10 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- ^ Blake, Eric (3 August 2018). Hurricane Hector Discussion Number 12 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 5 August 2018. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- ^ Blake, Eric (3 August 2018). Hurricane Hector Discussion Number 13 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ Eric, Blake (4 August 2018). Hurricane Hector Discussion Number 16 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ Blake, Eric (4 August 2018). Hurricane Hector Discussion Number 17 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ Brown, Daniel (5 August 2018). Hurricane Hector Discussion Number 20 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 5 August 2018. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- ^ Brown, Daniel (5 August 2018). Hurricane Hector Discussion Number 21 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- ^ Jelsema, Jon (6 August 2018). Hurricane Hector Discussion Number 24 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- ^ Wroe, Derek (7 August 2018). Hurricane Hector Discussion Number 27 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ Jelsema, Jon (7 August 2018). Hurricane Hector Discussion Number 28 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- ^ a b Jelsema, Jon (7 August 2018). Hurricane Hector Discussion Number 29 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Birchard, Thomas (8 August 2018). Hurricane Hector Discussion Number 34 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ Miyashima, Mika (4 August 2018). "Hawaii Island Officials Prepare for Hurricane Hector". KITV. Archived from the original on 5 August 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- ^ "Coast Guard Sets Port Condition 'YANKEE' for Big Island". BigIslandNow. 7 August 2018. Archived from the original on 17 August 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ "High surf lingers in Hector's wake". The Maui News. 10 August 2018. Archived from the original on 17 August 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ "Category 3 Hurricane Hector Nears Hawaii, Emergency Proclamation Signed". Big Island Video News. Big Island Video News. 7 August 2018. Archived from the original on 12 August 2018. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- ^ Worley, Tesia. "Absentee walk-in voting sites closed as Hector passes". kitv. Archived from the original on 12 August 2018. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- ^ "Hurricane Hector passing hundreds of miles south of Hawaiian islands". Star Advertiser. 8 August 2018. Archived from the original on 12 August 2018. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- ^ "Dozens rescued from south shore waters as Hector kicks up surf". Hawaii News Now. 9 August 2018. Archived from the original on 12 August 2018. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- ^ Kodama, Kevin (9 August 2018). Hurricane Hector Discussion Number 38 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ Kodama, Kevin (9 August 2018). Hurricane Hector Discussion Number 39 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ Houston, Sam (10 August 2018). Hurricane Hector Discussion Number 41 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ Birchard, Thomas (10 August 2018). Hurricane Hector Discussion Number 44 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ Philip Klotzbach [@philklotzbach] (11 August 2018). "Philip Klotzbach on Twitter" (Tweet). Retrieved 11 August 2018 – via Twitter.

- ^ Powell, Jeff (11 August 2018). Hurricane Hector Discussion Number 47 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ Jelsema, Jon (11 August 2018). Hurricane Hector Discussion Number 48 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ Burke, Robert (12 August 2018). Hurricane Hector Discussion Number 50 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ Houston, Sam (12 August 2018). Tropical Storm Hector Discussion Number 52 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ Houston, Sam (13 August 2018). Tropical Storm Hector Discussion Number 53 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ Philip Klotzbach [@philklotzbach] (August 12, 2018). "Philip Klotzbach on Twitter" (Tweet). Retrieved August 12, 2018 – via Twitter. See CSU website of author.

- ^ JMA Prognostic Reasoning #1 (Report). Japan Meteorological Agency. 13 August 2018. Archived from the original on 28 August 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ JTWC Prognostic Reasoning #1; Warning #54 (Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 13 August 2018. Archived from the original on 3 July 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ JMA Prognostic Reasoning #2 (Report). Japan Meteorological Agency. 14 August 2018. Archived from the original on 28 August 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ JTWC Prognostic Reasoning #2; Warning #55 (Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 14 August 2018. Archived from the original on 3 July 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ JMA Prognostic Reasoning #3 (Report). Japan Meteorological Agency. 14 August 2018. Archived from the original on 28 August 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ JTWC Prognostic Reasoning #3; Warning #56 (Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 14 August 2018. Archived from the original on 3 July 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ JTWC Prognostic Reasoning #5; Warning #58 (Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 14 August 2018. Archived from the original on 3 July 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ JMA Prognostic Reasoning #5 (Report). Japan Meteorological Agency. 14 August 2018. Archived from the original on 28 August 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ JMA Tropical Cyclone Advisory [00:00 UTC August 15, 2018] (Report). Japan Meteorological Agency. 15 August 2018. Archived from the original on 2 June 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ JMA Tropical Cyclone Bestrack (Report). Japan Meteorological Agency. Archived from the original on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Weather Service.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Weather Service.

External links

- The National Hurricane Center's advisory archive on Hurricane Hector

- The Central Pacific Hurricane Center's advisory archive on Hurricane Hector