Andrew Chatto

Andrew Chatto | |

|---|---|

Andrew Chatto | |

| Born | 11 November 1840 55 Pratt Street, Camden Town, London, England |

| Died | 15 March 1913 (aged 72) Larkrise, Aldenham Road, Radlett, Hertfordshire, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | Publisher |

| Years active | 1855 – 1912 |

| Known for | Honest dealing with his authors |

| Notable work | Increasing access to good literature through low cost editions |

Andrew Chatto (11 November 1840 – 15 March 1913) was an English book publisher who was renowned for the cordial relations he maintained with his authors.

Early life

Chatto[note 1] was born on 11 November 1840 at 55 Pratt Street, Camden Town London. His parents were the author William Andrew Chatto (1799 – 1864) and Margaret Roberts (c. 1804 – April 1852).[2][3][note 2]

Chatto was 15 when he joined the book-selling business of John Camden Hotten (12 September 1832 – 14 June 1873). He was probably apprenticed to Hotten at his father's instigation. He began as a 'runner'[note 3] at book auctions. Hotten had opened a small bookshop at London at 151b Piccadilly the year before Chatto joined the firm. as Hotten diversified into publishing and Chatto learned the trade as Hotten did.[5]: 10

Private life

Chatto is generally regarded as having had four illegitimate children by his mistress Catherine (later Katharine) Wallace Heard (c. 1839 – 11 October 1905)[6][note 4] (Mrs Radway), the daughter of Frederick Augustus Heard (1809 – second quarter of 1883), [7] a military tailor, and his wife Amelia Hollis Emmett (1809 – ) who had married on 37 October 1829 at St. Giles, Camberwell, London .[8] Catherine had married Joshua Carby Radway (c. 1836 – 27 December 1892)[9] in the second quarter of 1858 in the parish of St. James's in London. Census information suggests that Catherine had seven children, four of whom (namely Thomas, Andrew, Isabel, and Dorothea) were acknowledged in his will to have been sired by Chatto:[10]

- Frederick Augustus Radway,

- Michael John Radway,

- Joshua Carby Radway,

- Thomas Emmett Patrick Radway (later Thomas Chatto),

- Andrew Chatto Radway (later Andrew Chatto),

- Isabel Chatto,

- Dorothea Chatto.

The 1871 census found Chatto living in the same house as Katharine, her husband Mr Radway, and her two youngest children Joshua and Thomas. Thomas had been registered at birth as Thomas Emmett Patrick Radway. When Andrew was born later in the year, he was registered as Andrew Chatto Radway. The 1881 census found Chatto living at Dartmouth Park Hill Road, in the London Borough of Camden with Katharine, her son Thomas, the three children born to Katharine since the last census, her father, and a cousin. Thomas and Andrew had by then adopted the surname Chatto. Chatto always treated them as his sons and brought them into the business with him. Katharine's husband died on 27 December 1892, and in the first quarter of 1899 she re-married to Chatto at Holborn in London.[11]

Chatto & Windus

When Hotten died suddenly in 1873, Chatto bought the firm from Hotten's widow for £25,000 with money from the Poet William Edward Windus (1828–1910)[note 5] who became his partner in Chatto & Windus.[13]: 11 While Windus provide the finance, he was not an active partner, living for some of the time on the Isle of Man. Windus probably knew Chatto from when Hotten had published his first volume of verse in 1871.

At the time, there were five ways in which books might be published: There were:[14]

- Outright sale of copyright. The publisher took the whole risk, but could make large profits. Jane Austen for example sold the rights of Pride and Prejudice for £110 and saw the publisher make a profit of £450 on the first two editions alone.[15] Sometimes the sale of copyright was limited to a number of copies or a number of years.

- Profit sharing. The publisher runs the risk, although sometimes the author is asked to contribute a fixed amount, and shared the profits with the author. This is subject to the risk that the publisher inflates the costs, to reduce the apparent profit.

- Royalties. The publisher takes the risk and agrees to pay royalties on every copy, on every copy over a certain number, on every copy after production costs are met (subject to the risk of inflated costs). Sometimes the royalties could increase after a particular number of copies.

- Publishing on commission. The author takes the risk, pays the costs of publishing, and the publisher takes a commission on each book sold (again subject to the risk of inflated costs). This is nowadays frowned upon as vanity publishing, but it was regarded as a legitimate form of publishing in the 19th century – this was the system that Jane Austen and many other authors of the time used.

- Publishing on subscription, used more in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, where a number of subscribers agree to buy a copy and the money is used to pay for publication. The publisher might be paid a commission on sales. This was the way in which the Record of the Ripon Millenary Festival was published in 1892.[16]

Conflicts arose between publishers and authors because of:

- Disagreement over the value of the copyright, or the failure to publish. Jane Austen bought back the copyright for Susan after the publisher whom she had sold it to had not published it.

- The unwillingness of publishers to accept books on a royalty basis, and even if they did, disagreements on the rates of royalties.

- Disagreements on amounts of the publishers costs.

- Delays in payments to authors.

The poet John Campbell (1777–1844) is said, during the height of the Napoleonic Wars to have induced a group of authors to drink to the health of Napoleon on the basis that he had once shot a publisher.[17] Mark Twain told the Authors' Club in London in 1899 that It is of service to an author to have a lawyer, there is something so disagreeable in having a personal contact with a publisher. It is better to have a lawyer – and lose your case. Clearly relations between authors and their publishers were often fraught, and the risk of bad relations increased when publishers were less than honest in their dealings. Despite his speech, Chatto enjoyed very good relations with Mark Twain.[5]: 14

When Chatto took over from Hotten, there were a number of legacy problems, resulting in part from Hotten's somewhat shady business practices.[note 6] In particular, Hotten had alienated the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne by paying him little if any of the profits from the publication of his Poems and Ballads which had sold well. Chatto mended fences by sending Swinburne a cheque for £50 and a formal request to publish his work. Chatto subsequently published Swinburne's Bothwell.

Peters contrasted Chatto who was not only an active and successful publisher, but an honest one, compared with Hotten, who was something of a rogue.[19] Hotten had spent years in the United States and knew more about American literature than any other publisher in London. He made ruthless use of this knowledge to pirate works by American authors, as few had taken any steps to copyright their work in England.[13]: 5

One of the Hotten's victims was Mark Twain, but Chatto managed to establish good relations with him and they became good friends.[5]: 86 Chatto worked his charm with other authors also, and Robert Louis Stevenson said: If you don't know that you have a good author, I know I have a good publisher. Your fair, open and handsome dealings are a good point in my life, and do more for my crazy health than has yet been done by any doctor.[13]: 14

In 1876, Chatto brought in Percy Spalding (third quarter of 1854 – 13 August 1930)[20][21] to help him manage the firm. Spalding was much more of a financial manager than a literary man, so Chatto was left to decide editorial matters himself.[22]

During the 1880s Chatto was determined to make Chatto & Windus the leading publisher of novels in London, and set out to dramatically increase their list.[23]: 581 Chatto invested in expanding the list, buying the rights to the existing works of popular novelists such as Ouida, Wilkie Collins and others. He then reprinted them in cheap editions.[4] He bought the remaining stock and copyrights of henry George Bohn's for £20,000. His strategy was to dramatically increase the firm's share of the novel market, and be the first choice for novelists. He certainly won the good will of writers.[13]: 13 The purchase of Bohn's stock also expanded the range and type of books that he published.

Chatto saw periodicals as another possible outlet for the firm's authors (and for the intellectual property that the firm had bought.) He bought The Belgravia and its associated annual. He published The Idler from 1892 to 1911, and he also handled The Gentleman's Magazine.[4]

Frank Arthur Swinnerton, who worked at the firm, recalls Chatto as: a gentle elderly man with a rolling walk, genially sweet in manner to every member of his staff, and much loved.[24]

Rujub the Juggler

The story of Rujub the Juggler illustrates two facets of Chatto's character, his support and encouragement for authors, the reason why Sutherland referred to the firm as the "hustlers" of the book trade.[25]: 369 Chatto recognised and encouraged G. A. Henty's ability as a writer for adults.[note 7] Chatto published four of Henty's eleven adult novels. Of these, Rujub, the Juggler was the biggest success, selling 11,000 copies, with most of these shortly after initial publication.[26]Arnold said that the book had a period charm which he found surprising. and suggested that Henty's adult novels, which sold less than his juvenile titles, had been generally underrated.[27]

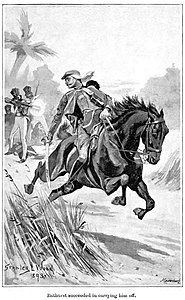

Rujub was first published in book form[note 8] as a three-decker, or three-volume novel,[note 9] without illustrations on 23 February 1893. The initial print run was for 500 copies. Chatto recognised that juveniles were also reading the Henty novels, and he published a single volume edition with eight illustrations by Stanley L. Wood in time for the Christmas market in 1893. Chatto had tremendous belief in Henty, and he ordered a print run of 3,000 for the illustrated edition (he had already printed 500 of the three-volume edition, and 2,000 of a single volume unillustrated colonial edition.)[23]: 238 Chatto's actions sailed close to the wind on two accounts:

- Chatto has agreed to the condition, set by the two largest circulating libraries, Smith's and Mudie, in their simultaneous circulars on 27 June 1894, that, among other things, publishers could not issue a cheaper edition in the UK within twelve months of its first acceptance by the libraries.[note 10] The cheaper illustrated one-volume edition was published within nine months of the three-volume library edition.[30]

- Henty was under an exclusive contract for juvenile fiction with Blackie and Son. While an unillustrated three-volume novel was unquestionably for the adult market, the same could not be said of an illustrated single volume. Henty was concerned, and grew even more so in 1899 when Chatto released the book as a presentation edition.[note 11]

-

Page 011

-

Page 075

-

Page 170

-

Page 182

-

Page 221

-

Page 273

-

Page 305

-

Page 329

Later life

Katharine died on 11 October 1905. The 1911 census found Chatto living with his daughter Isobel and her family in Larkrise, Aldenham Road, Radlett, Hertfordshire. Chatto retired from publishing in 1912. He died the following year, on 15 March 1913, at his daughter's home. He was cremated at Golders Green on 18 March 1913. His estate was valued at just over £14,000, and probate was granted to his sons Thomas and Andrew.[31]

His daughter Isobel retained possession of his papers, including handwritten letters, manuscripts and a few books, and sold them at Sotheby's in 1916.[5]: 10 In dying the year after he retired, Chatto was following the example of Windus, who retired from the firm in 1909 and died on 7 June of the following year.[12]

Notes

- ^ The name comes from an estate known as the lands of Chatto, on the Kale Water, in the former county of Roxburghshire. The lands were originally granted to the Norman William de Chetue or Chatthou.[1]

- ^ The Government Records Office Death Index shows that Margaret died in the second quarter of 1852, and the parish records show that she was buried on 8 April 1852. therefore she died in April.[4]

- ^ A runner brings items from where they are displayed or stored up to the auctioneer so that they can be displayed during the bidding.

- ^ Initially spelled Catherine, and later spelled Katharine.

- ^ Sometimes confused with the diffident English Pre-Raphaelite painter William Lucas Windus (1822–1907). Windus the poet also painted watercolours.[12]

- ^ Hotten was also a pornographer, while still remaining respectable.[18]

- ^ While Henty has hugely successful as an author of juvenile fiction he had less success with his novels for adults.[23]: x

- ^ It had been published as a newspaper serial in 1892 in Australia in the Sydney Echo,[28] and in the United States in The Boston Globe.[29]

- ^ This had been the standard format for adult novels, as it suited the circulating libraries, see Appendix II of Newbolt[23] for a discussion on the economics of the three volume novel. Essentially the circulating libraries demanded that novels be produced in three volumes as this raised the price, thus increasing the attractiveness of libraries against individual purchase, as well as encouraging subscribers to take out a higher-rate subscription (as you could not take out three volumes at a time with the cheaper subscriptions).[23]: 563

- ^ The delay to cheaper editions was to enable the circulating libraries to dispose of their extra copies on the second-hand market.[23]: 582

- ^ Juvenile books were often given as school prizes or Christmas Gifts, so publishers produced presentation editions for this purpose.

References

- ^ "Last name: Chatto". SurnameDB. 2017. Retrieved 2020-05-21.

- ^ London Metropopolitan Archives. "Burials in the Parish of Saint Pancras, in the County of Middlesex, in the year 1852: Reference Number: p90/pan1/190". London, England, Church of England Deaths and Burials, 1813-2003. London: London Metropolitan Archives.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Weedon, Alexis (2004). "Chatto, Andrew (1840–1913)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/47445. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b c d Welland, Denis (1978). Mark Twain in England. Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey: Humanities Press. ISBN 0-391-00553-7. Retrieved 2020-08-05 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ "Wills and Probates 1858-1996: Pages for Chatto and the year of death 1905". Find a Will Service. p. 61. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ Ancestry.com (2014). England, Select Marriages, 1538–1973. Provo, Utah: Ancestry.com.

- ^ "Wills and Probates 1858-1996: Pages for Radway and the year of death 1893". Find a Will Service. Retrieved 2020-05-20.

- ^ Last Will and Testament of Andrew Chatto. 1909-04-05. Retrieved 2020-06-12.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Mr. W. E. Windus". The Times (Thursday 09 June 1910): 13. 1910-06-09.

- ^ a b c d Warner, Oliver (1973). Chatto and Windus: A Brief Account of the Firm's Origin, History and Development. London: Chatto & Windus.

- ^ Sprigge, S. Squire (1890). The Methods of Publishing. London: Henry Glaisher.

- ^ Fergus, Jan (1997). "The professional woman writer". In Copeland, Edward; McMaster, Juliet (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Jane Austen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 21 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ Harrison, W. (1892). "Preface". Ripon Millenary 1886, Illustrated by John Jellicoe and Herbert Railton. Ripon: W. Harrison. pp. iii. Retrieved 2020-03-27.

- ^ "News of the Day". Birmingham Daily Post (Birmingham, England) (Thursday 10 March 1887): 4. 1887-03-10.

- ^ Marcus, Steven (1985). "Pisanus Fraxi, Pornographer Royal". The Other Victorians: A Study of Sexuality and Pornography in Mid-Nineteenth-Century England. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 67-73.

- ^ Peters, Catherine. "The Law and the Lady (1874-1879)". The King of Inventors: A Life of Wilkie Collins. pp. 369–70.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ "Deaths". The Times (Friday 15 August 1930): 1. 1930-08-15.

- ^ Ezra Greenspan; Jonathan Rose (2003-09-01). "The Case of Frank Swinnerton". Book History. Penn State Press. p. 179. ISBN 0-271-02330-9. Retrieved 2020-05-22 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e f Newbolt, Peter (1996). G.A. Henty, 1832-1902 : a bibliographical study of his British editions, with short accounts of his publishers, illustrators and designers, and notes on production methods used for his books. Brookfield, Vt.: Scholar Press. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- ^ Swinnerton, Frank (1952). A Bookman's London. New York: Doubleday & Co. p. 50.

- ^ Sutherland, John (1989). The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ Newbolt, Peter (2006-05-25). "Henty, George Alfred (1832–1902)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33827. Retrieved 2020-05-19. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Arnold, Guy (1980). "The Henty Range". Held Fast for England: G. A. Henty, Imperialist Boys Writer. London: Hamish Hamilton. pp. 87 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ "Advertisement for "In the Days of the Mutiny", beginning today in the "Sydney Echo"". The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney, Australia) (Saturday 09 April 1892): 8. 1892-04-09.

- ^ Henty, George Alfred (1892-06-25). "In the Days of the Mutiny: A military novel". The Boston Globe (Boston, Massachusetts) (Saturday 25 June 1892): 3 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ "Chatto and Windus's New Novels". London Evening Standard (Wednesday 01 November 1893): 4. 1893-11-01.

- ^ "Wills and Probates 1858-1996: Pages for Chatto and the year of death 1913". Find a Will Service. Retrieved 2020-05-20.