Severo Fernández

Severo Fernández | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Photograph of Severo Fernández in 1898. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 24th President of Bolivia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 19 August 1896 – 12 April 1899 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice President | Rafael Peña de Flores Jenaro Sanjinés | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Mariano Baptista | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | José Manuel Pando | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10th Vice President of Bolivia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

First Vice President | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 11 August 1892 – 19 August 1896 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | Mariano Baptista | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | José Manuel del Carpio | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Rafael Peña de Flores | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Severo Fernández Alonso Caballero 15 August 1849 Sucre, Bolivia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 12 August 1925 (aged 75) Potosí, Bolivia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Conservative | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | Filomena Perusqui Aramayo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parent(s) | Ángel Fernández Casimira Caballero | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | University of Saint Francis Xavier | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Severo Fernández Alonso Caballero (15 August 1849 in Sucre – 12 August 1925) was a Bolivian lawyer and politician who served as the 24th president of Bolivia from 1896 to 1899 and as the tenth vice president of Bolivia from 1892 to 1896. He is best remembered as the last president of the 15-year period of Conservative Party hegemony (1884–99).

Political career

Son of Ángel Fernández and Casimira Caballero, he studied law at the Universidad Mayor, Real y Pontificia de San Francisco Xavier de Chuquisaca and dedicated himself fully to his profession. As a lawyer, he worked closely with the big mining companies and made his fortune, especially with silver tycoons like Gregorio Pacheco, Aniceto Arce, and Francisco Argandoña.[1]

He worked as a journalist for El Regime Legal and El País de Sucre, where he distinguished himself as an excellent writer and propagandist.[2] He was Minister of the Interior for Aniceto Arce and Minister of War for Mariano Baptista. He was also the Vice President of the Baptista government, and, in that capacity, presided over the National Congress.

President of Bolivia

Embittered liberals and administration

Representing the Conservative Party, he defeated the Liberals in the 1896 general elections and became president on August 28 of that year. He was then 47 years old. The liberals boycott the result of the elections and would oppose him in every possible occasion. One such detractor was congressman Atanasio de Urioste Velasco, who would write a popular pamphlet called La política afeminada de Severo Fernández Alonso, in which he called the government weak and soft, among many other insults directed at Fernández.[3]

A disgruntled Liberal Party had become increasingly frustrated during the many years of Conservative dominance, often attained by electoral fraud. After 1894, led by the combative José Manuel Pando, a former military hero in the War of the Pacific, the Liberals' calls for anti-government rebellions became more strident, but they were always neutralized by a loyal military establishment.[4]

During his government, an engineering school was founded in Sucre, began construction of the first telegraph line to the east, built the suspension bridge over the Pilcomayo, completed the Sucre Government Palace, and founded Puerto Alonso.[5] Throughout Fernández's presidency, the center of power in the country shifted to La Paz, where the Liberals had a lot of support. Thus, by 1898, only the mining cities of Sucre and Potosí remained loyal to the Conservatives and the government.

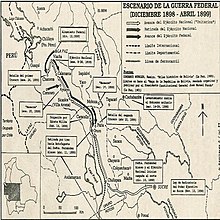

Civil War of 1898-1899

Prelude and the "Radicatory Law"

Fernández wanted to settle the decade-long debate regarding what city was officially the Bolivian capital. Up until 1880, the seat of executive power was wherever the current president resided. Hence, Congress met, between 1825 and 1900, on twenty-nine occasions in Sucre, twenty in La Paz, seven in Oruro, two in Cochabamba and one in Tapacarí. Officially, the capital of Bolivia was Sucre since the presidency of Antonio José de Sucre, remaining as such over the years due to the lack of resources to build a new capital and the influence of its aristocracy. However, by the 1880s, conservative presidents chose to settle in Sucre, making it the de facto capital of the country.[6]

On October 31, 1898, the deputies of Sucre proposed to definitively install the executive capital in Sucre, known as the "Radicatory Law". However, their La Paz counterparts proposed that the Congress should move to Cochabamba (a neutral place), a proposition which was rejected.[7] The liberals seemed to initially accept the plan to make Sucre the official capital. The liberals had don so strategically since if they vetoed they would provoke the inhabitants of the capital, however, if it was approved they could convince the people and the garrison of La Paz (under the orders of Colonel José Manuel Pando) to mount an insurrection. On November 6, there was a massive riot in La Paz which demanded called for federalism and for their city to be the capital. On November 14, a Federal Committee was created and chaired by Colonel Pando while its deputies defended their cause in Congress.[6] Three days later, the "Radicatory Law" was approved, with Sucre as the capital and seat of executive power. On November19, it was officially promulgated.

In response, on December 12, with the people of La Paz in their favor, a Federal Board of Liberals and some authorities who switched sides (the Prefect and Commander General Serapio Reyes Ortiz and the Minister of Instruction Macario Pinilla) was formed.[7] Pando's liberals allied themselves with Pablo Zárate Willka, cacique of the Altiplano.

Outbreak of war

After these events, the deputies from La Paz withdrew to their department by order of the Federal Board. The people of La Paz received their representatives with exalted cheers and acclamations.[8] The overthrow of Fernández had now become a main objective of the federalists. In juxtaposition to La Paz, in Sucre, there were public demonstrations in support of the government.[7]

Fernández decided to march on La Paz with the three divisions stationed in Sucre (Bolívar, Junín and Hussars). In Challapata, he found out that the rebels had acquired more than two thousand weapons, so he called for the recruitment of volunteers in the capital.[9] Two brigades were formed, the first was made up of the 25 de Mayo battalion and the Sucre squadron. These were made up of upper-class youths with their own horses and weapons, and included the Olañeta battalion and the Monteagudo squadron, made up of young men from popular classes. During their march to reinforce the president, the government forces plundered the indigenous populations in the countryside.[10]

The government's first brigade encountered Pando and numerous warriors in Cosmini, being forced to take refuge in the parish of Ayo Ayo, where they were massacred on January 24, 1899.[6] In Potosí, the population was openly against helping the government forces, meanwhile in Santa Cruz and Tarija there was a clearly neutral stance. Among the indigenous communities of Cochabamba, Oruro, La Paz and Potosí there are uprisings in favor of the Liberals.[7]

The decisive confrontation of the civil war was the battle of the Segundo Crucero, on April 10, 1899, where the president and Pando met. After four hours of combat, Pando's troops were victorious. The defeated withdrew to Oruro and, shortly after, Fernández went into exile.

Aftermath, death, and legacy

Fernández emigrated to Chile, where he remained for some years. He returned to Bolivia during the government of Eliodoro Villazón, who accredited him as plenipotentiary minister in Peru and Argentina. In 1914, he was elected Minister of the Supreme Court of Justice and, as such, President of the Judiciary. Finally, in 1922, he was elected Senator for Chuquisaca and became president of the National Congress. He died on August 12, 1925.[1]

Legacy

Fernández would be the last president of the Conservative rule which had dominated the country for over a decade. However, the growing importance and power of La Paz, a city dominated by the Liberals, and the dispute over the location of the capital would destroy the Conservative power base located in Sucre. To this day, La Paz remains the most important city in Bolivia.

The municipality of Puerto Fernández Alonso is named after him.

References

- ^ a b Campero, Isaac S. (1895). Estadistas bolivianos: Severo Fernández Alonso (in Spanish). Imp. de "La Revolución".

- ^ Veredicto nacional: Historia de Bolivia (in Spanish). Imp. de "El Tiempo". 1897.

- ^ Senadores, Bolivia Congreso Nacional Cámara de (1907). Proyectos e informes (in Spanish).

- ^ López, Manuel Ordóñez; Crespo, Luis S. (1912). Bosquejo de la historia de Bolivia (in Spanish). Imprenta Boliviana, H. Heitmann.

- ^ Smale, Robert L. (2010). "I Sweat the Flavor of Tin": Labor Activism in Early Twentieth-century Bolivia. University of Pittsburgh Pre. ISBN 978-0-8229-7390-4.

- ^ a b c Lorini, Irma (2006). El nacionalismo en Bolivia de la pre y posguerra del Chaco (1910-1945) (in Spanish). Plural editores. ISBN 978-99905-63-91-7.

- ^ a b c d Medinaceli, Ximena; Soux, María Luisa (2002). Tras las huellas del poder: una mirada histórica al problema de la conspiraciones en Bolivia (in Spanish). Plural editores. ISBN 978-99905-64-56-3.

- ^ Pacheco, Mario Miranda (1993). Bolivia en la hora de su modernización (in Spanish). UNAM. ISBN 978-968-36-3273-9.

- ^ Manuel, Alcántara; Mercedes, García Montero; Francisco, Sánchez López (1 July 2018). Estudios sociales: Memoria del 56.º Congreso Internacional de Americanistas (in Spanish). Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca. ISBN 978-84-9012-925-8.

- ^ Mendieta, Pilar (2010). Entre la alianza y la confrontación: Pablo Zárate Willka y la rebelión indígena de 1899 en Bolivia (in Spanish). Plural editores. ISBN 978-99954-1-338-5.

- 1849 births

- 1925 deaths

- 19th-century Bolivian politicians

- 20th-century Bolivian politicians

- 19th-century Bolivian judges

- 20th-century Bolivian lawyers

- Ambassadors of Bolivia to Argentina

- Ambassadors of Bolivia to Peru

- Bolivian expatriates in Chile

- Bolivian diplomats

- Bolivian people of Spanish descent

- Candidates in the 1896 Bolivian presidential election

- Conservative Party (Bolivia) politicians

- Defense ministers of Bolivia

- Foreign ministers of Bolivia

- Leaders ousted by a coup

- Members of the Senate of Bolivia

- People from Sucre

- Presidents of Bolivia

- Presidents of the Senate of Bolivia

- Vice presidents of Bolivia