André Devambez

André Victor Édouard Devambez (26 May 1867 – 18 March 1944) was a French painter and illustrator. best-known his whimsical illustrations of children's books and his dramatic paintings of Paris scenes and of early airplanes from a viewpoint high above. He was professor at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, a member of the French Academie des Beaux-Arts, and a Commander of the French Legion of Honor, but his work is little known today aside from nine paintings found in the Musée d'Orsay, and occasional special exhibitions.[1]

Biography

André Devambez was born on 26 May, 1867. His father, Édouard Devambez, was the son of a butcher, who became an engraver. His father met his wife, Catherine Véret, when they were both apprentices in engraving.[2] In 1870 his parents opened their own studio at Passage des Panoramas, called the Maison Devambez, which he built into a major publishing house, commissioning and selling engravings and other art.[3]

From an early age André wanted to become an artist. His father arranged private lessons with Gabriel Gouray, a former student of Jean-Léon Gérôme, who encouraged the young Devambez to become a history painter. In 1884 took private lessons from Jules Lefebvre at the Académie Julian.[4] In 1885 he succeeded in the entry examination to the École des Beaux-arts, where he studied with Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant and Gustave Boulanger. In 1890, He was awarded the Prix de Rome for his somber depiction of the denial of Peter which gave him a position to study and paint for five years at the Villa Médicis of Academy in Rome.

His studies were interrupted by military service in until November 1892, He resumed his studies in Rome in 1893, when he submitted his required finished work to the Academy, a painting of the Prodigal Son. Devambez purchased a camera and posed in costume for the painting himself. In 1894 he submitted to the Academy a painting of "The Legend of Saint Agatha", with multiple characters in varied poses; then, in 1898, a monumental work depicting "The Conversion of the Madeleine", which obtained for him the Medal of Second Class. In 1900 he married Cécile Richard, the daughter of a chemist from Alsace. They had two children, Pierre and Valentine. In 1899 he was elected a member of the Société des Artistes Français, at whose annual Salon he exhibited, and in 1905 he became a chevalier of the Légion d'honneur.[5]

He also began turning his attention to illustrations, and smaller genre works. In 1898 he illustrated a novel by Emile Zola, "La Fete de Coqueville". In May 1913 he had his first personal exhibition at the gallery of Georges Petit. When the First World War began in 1914, he was too old to be drafted into the army, but volunteered to be a battlefield artist, and to paint camouflage to conceal of army positions in the front lines. On June 3 1915, at Amiens, he was seriously wounded in the leg and the left eye by an exploding German artillery shell. He spent a long convalescence in the hospital. In August 1915 was awarded the Croix de Guerre for his services.[6]

In 1929, he was named head of the painting section at the École des Beaux-Arts, France's most prestigious art school,[7] a position he retained until 1937. He opened the atelier for the first time to women students. That same year, he was elected to Seat #9 at the Académie des Beaux-Arts, which he held until his death.

IN 1934, he was awarded the unusual position of official painter of the Ministry of Aviation, where he used his art to publicise the growing aviation industry. In the same year he was named a member of the Fine Arts Commission for the 1937 Paris International Exposition; his paintings of the Exposition, made from high above on the Eiffel Tower, gave a striking new perspective to the Exposition. In 1938, he was named a Commander in the Legion of Honor.[8]

He died at his home at the Pavillon Raffet at the Villa Adrienne on 18 March, 1944, at the age of seventy-seven.[9]

Paintings

Painting Paris and the Parisians

-

Place Pigalle

-

La Charge (1902–1903), Musée d'Orsay

-

"The Palace of Chaillot during the 1937 International Exposition, see from the Eiffel Tower (1937)

-

Concert by the Colonne Symphony Orchestra

Paris and the Parisians were the subjects most often painted by Devambez, and he often depicted them from an unusual perspective, from above. In his youth he lived in the sixth floor of a building at the corner of boulevard Montmartre and rue Vivienne, and saw the activity and crowds in the Paris streets spread out below him. This was translated into a series of paintings.

There are nine of his works in the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, including his best-known painting, La Charge. This dramatic scene, painted in about 1902, is an aerial view of a violent nighttime confrontation as the Paris police broke up a demonstration of labor union workers on strike on the Boulevard Montmartre. Ironically, though Devambez was a sympathiser of the strikers, the painting ended up hanging in the office of the Prefect of Police, Chiappe, who had ordered the repression of the strike.[10]

In 1937 he received a commission from the Paris International Exposition to paint an aerial view of the new Palace of Chaillot at the Exposition, made from the second level of the Eiffel Tower. It showing the immense crowd at the Exposition on both sides of the Seine and on the bridge between. The painting also made abundant use of the color blue, which was the official color of the Exposition. It now hangs in the Museum of Fine Arts in Rennes.[11]

Aviation and technology

-

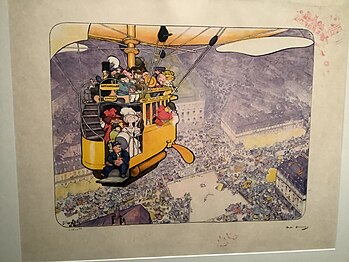

A whimsical "Dirigible-Bus" over Paris (1909)

-

"The only bird which flies above the clouds" (1910), Musée d'Orsay

-

Fantastic aircraft (1911-1914)

As an artist Devambez was attracted to scenes of modern life and modern technology, particularly aviation. In 1909, he made a colour lithograph of a "Dirigible-Bus", a whimsical imaginary vehicle that combined the features of Paris municipal bus and a balloon. Between 1909 and 1010, he frequented air shows in Paris and other cities, and illustrated the aircraft, sometimes painting them as they would be seen seen from high above. These illustrations appeared in the popular magazine "L'Illustration", and there publications, while a group was presented at the Paris Salon.

In 1910, he was invited to provide twelve decorative panels for the new French Embassy in Vienna,[7] He chose the subject of modern inventions, painting the metro, an omnibus, airships, the Paris Metro, ships and aeroplanes. He completed designs for the twelve panels, but due to a financial scandal in another part of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the project was left unfinished, and the paintings were not installed. . In 1934 André Devambez was appointed the first official artist to the newly created French Air Ministry. The smaller panels he made survived in the archives of the Ministry. They were finally put into place at the Vienna Embassy in a newly-designed gallery in 1993.[12]

One painting of the series is on display in the Musée d’Orsay. Entitled Le seul oiseau qui vole au-dessus des nuages ("The only bird that flies above the clouds"), it employs a breathtaking downward perspective to show a biplane flying above a cloud-mass, with glimpses of the ground far below, and the shadow of the aircraft on the clouds.

In addition to painting aircraft, Devambez created illustrations of the new Paris Metro, showing the crowds gathered on the quays, and whimsical cartoons of the earliest automobile shows and races, including the Paris-Berlin automobile race that took place in July 1901.

The First World War

-

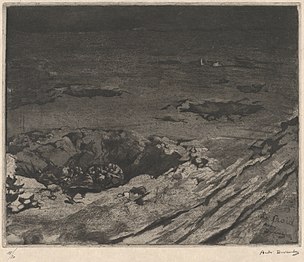

Etching of Front Lines in the First World War (1917)

-

Etching of front lines in the First World War (1917)(Metropolitan Museum of Art)

-

Front Lines in the First World War (1917)

-

Residents of French town lining up for coal (1917)

When the First World War began in 1914, Devambez was forty-seven years old, too old to be drafted. Nonetheless he volunteered for service as a combat artist and to paint camoulflage, and made serveral trips to the front. On June 3, 1915, he was badly injured by an exploding German shell. His first paintings of the war were based on photographs, and were rather formal. In 1917. he published an album of twelve etchings boded on his experience at the front, which were more dramatic and intimate. The subjects included "Cold", "Shell Holes"; "The fire" "The rain"; "The spy"; "Storms"; "The hostages"; "The reserves"; "Coal"; "The madman" "The Fire:; "Coal" and "Shrapnel". which were his personal views of the war. these were published in an edition of 150 copies in 1915. He often depicted the scenes as viewed from high above.[13]

Portraits

-

"The misunderstanding" (1903-1904)

-

"Reading", his daughter Valentine and son Pierre (1914)

-

His children, Valentine and Pierre (1925)

Lithographs - The Parisians

-

Lithograph of toys at Galeries Lafayette department store (1907)

-

"Waiting for the Metro" (1910) (Lithograph enhanced with Guache and water colors)

-

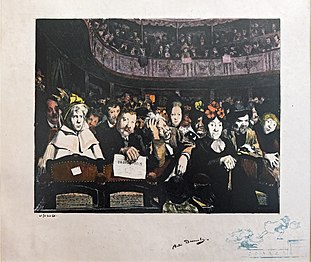

"Premiere at the Montmartre Theater (1901) (Colored Lithograph)

The "Tout-Petits" and "Ulysses and Calypso"

-

"The Fete of the Fairies" (1922)

-

"Ulysses and Calypso" (1936)

The "Tout-Petits" are a genre of very small paintings made by Devambez, which usually illustrated an anecdote or joke. They were generally only a few dozen centimetres in size, and sometimes were set in very elaborate frames, and became a kind of display object, between a sculpture and a painting.

In 1936, during the Great Depression, he faced some financial difficulties, and reverted to his earlier style to produce a large and highly decorative work, full of symbolism and color, on the Classical Greek theme of Ulysses and Calypso. It was purchased by the Museum of the Petit Palais.[14]

Book Illustration

-

Engraving from "Gullver's Travels" (1911) in "Illustration"

-

"Gulliver Steals the Fleet of the Big-Enders", Illustration from "Gulliver's Travels" (1921)

-

Image from "Gulliver's Travels" in "Illustration" (1911)

André Devambez provided illustrations for books and magazines. Auguste a Mauvais Caractère (Devambez, 1913) was a children's book, with André's own illustrations hand-coloured by the master of stencil technique, Jean Saudé; the original illustrations were exhibited the following year at the Palais de Glace. This was the first of a number of children's books, including Histoire de la petite Tata et du Gros Patapouf and Les Aventures du Capitaine Mille-Sabords, nos. 8 and 9 in a series of undated stories issued in concertina format "Chez l’auteur". These children's stories were probably intended for the amusement of his son, Pierre Devambez (1902–1980) and his daughter Valentine (1907-?). His son became an archeologist and later became curator of Greek and Roman antiquities at the Louvre,

Books illustrated by André Devambez include La Fête à Coqueville by Émile Zola (Éditions Fasquelle, 1899);[7] Le Poilu a Gagné la Guerre by Charles Le Goffic (1919); and Les Condamnés à Mort by Claude Farrère (Édouard-Joseph & L’Illustration, 1920). He also contributed illustrations to Le Figaro Illustré, Le Rire, and L'Illustration.

A retrospective of his work was held at the Musée de Beauvais in 1988. A large exposition of his paintings and illustrations was held at the museum of art of the City of Paris at the Petit Palais in 2022.

References

- ^ Faton, Jeanne, "André Devambez, Vertiges de l'Imagination", L'Objet d'Art - Hors-Série, December 2022 (in French)

- ^ Faton (2022), pg. 67

- ^ "Grand Guerre en Dessin- André Devambez" (in French)

- ^ Bénézit, Dictionnaire des peintres, vol. 4, p. 524.

- ^ Faton (2022), pg. 67

- ^ Faton (2022), pg. 67

- ^ a b c Biographical notes @ the Larousse Online.

- ^ Faton (2022), pg. 67

- ^ Faton (2022), pg. 67

- ^ Faton 2022) p. 25

- ^ Faton 2022) p. 35

- ^ Faton 2022) p. 35

- ^ Faton 2022) p. 35

- ^ Picture caption at the Devambez exhibition, the Petit Palais, December 2022

Bibliography (in French)

- Faton, Jeanne, Director of Publication, "André Devambez, Vertiges de l'Imagination", L'Objet d'Art - Hors-Série, December 2022 (in French)

- Noémie Bertrand and Michel Ménégoz, "André Devambez, 1867-1944", exhibition catalog, 4 June-4 July 1992, Ville de Neuilly-Plaisance, 1992

External links

- 1867 births

- 1944 deaths

- French illustrators

- 19th-century French painters

- French male painters

- 20th-century French painters

- 20th-century French male artists

- Painters from Paris

- Members of the Académie des beaux-arts

- French engravers

- French children's book illustrators

- Prix de Rome for painting

- 20th-century French printmakers

- 19th-century French male artists