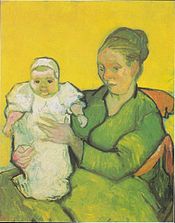

Paintings of Children (Van Gogh series)

| Portrait of Camille Roulin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Vincent van Gogh |

| Year | 1888 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 40.5 cm × 32.5 cm (15.9 in × 12.8 in) |

| Location | Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam |

Vincent van Gogh enjoyed making Paintings of Children. He once said that it's the only thing that "excites me to the depths of my soul, and which makes me feel the infinite more than anything else." Painting children, in particular represented rebirth and the infinite. Over his career Van Gogh did not make many paintings of children, but those he completed were special to him. During the ten years of Van Gogh's career as a painter, from 1881 to 1890, his work changed and grew richer, particularly in how he used color and techniques symbolically or evocatively.

His early works were earth-toned and dull. After a transformative period in Paris, Van Gogh embarked on his most prolific periods starting in Arles, in the south of France and continuing until his final days in Auvers-sur-Oise. During those times his work became more colorful and more reflective of influences, such as Impressionism and Japonism. Japonism influences are understood in the painting of a young girl, La Mousmé. Among others, he was inspired by the work of Jean-François Millet which he emulated in First Steps and Evening: The Watch.

Van Gogh enjoyed painting portraits when he had available models. Possibly the greatest impact to his paintings of children came out of the friendship with Joseph Roulin and the many paintings of his family.

Portraits

Van Gogh, known for his landscapes, seemed to find painting portraits his greatest ambition.[1] He said of portrait studies, "the only thing in painting that excites me to the depths of my soul, and which makes me feel the infinite more than anything else."[2]

To his sister he wrote, "I should like to paint portraits which appear after a century to people living then as apparitions. By which I mean that I do not endeavor to achieve this through photographic resemblance, but my means of our impassioned emotions -- that is to say using our knowledge and our modern taste for color as a means of arriving at the expression and the intensification of the character."[1]

Convey comfort

Of painting portraits, Van Gogh wrote: "in a picture I want to say something comforting as music is comforting. I want to paint men and women with that something of the eternal which the halo used to symbolize, and which we seek to communicate by the actual radiance and vibration of our coloring."[3]

Infants

Van Gogh saw "something deeper, more intimate, more eternal than the ocean in the expression of the eyes of a little baby when it wakes in the morning." Infants which represented "rebirth and immortality" to Van Gogh and lightened his mood. When he had the opportunity, Van Gogh enjoyed painting them.[4]

Peasant genre

The "peasant genre" that greatly influenced Van Gogh began in the 1840s with the works of Jean-François Millet, Jules Breton, and others. In 1885 Van Gogh described the painting of peasants as the most essential contribution to modern art. He described the works of Millet and Breton of religious significance, "something on high."[5] Referring to painting of peasants Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo: "How shall I ever manage to paint what I love so much?"[6]

This was a decided transition in approach to paintings from his earlier works influenced by Dutch masters, such as Rembrandt. His goal at that time was to paint them as he saw them and based upon his emotional response to them. His early works of peasants were in muted tones. As he was influenced by Impressionism and the use of complementary colors, his style changed dramatically.[7]

Models

As much as Van Gogh liked to paint portraits of people, there were few opportunities for him to pay or arrange for models for his work. He found a bounty in the work of the Roulin family, for which he made several images of each person. In exchange, Van Gogh gave the Roulin's one painting for each family member.[8]

Netherlands

Boy Cutting Grass with a Sickle, made in 1881, is owned by the Kröller-Müller Museum.[9]

Of a study that Van Gogh made for Girl in a Wood or Girl in White in the Woods,[10] he remarked at how much he enjoyed the work and explains how he wishes to trigger the audience's senses and how they may experience the painting: "The other study in the wood is of some large green beech trunks on a stretch of ground covered with dry sticks, and the little figure of a girl in white. There was the great difficulty of keeping it clear, and of getting space between the trunks standing at different distances - and the place and relative bulk of those trunks change with the perspective - to make it so that one can breathe and walk around in it, and to make you smell the fragrance of the wood."[11]

In The Girl in the Woods the girl is overshadowed by the immense oak trees. The painting may be reminiscent for Van Gogh of the times in his youth he fled to the Zundert Woods to escape from his family.[12]

|

|

|

A Girl in the Street, Two Coaches in the Background and Peasant Woman with Child on Her Lap are both part of private collections.[13]

Van Gogh was attracted to Sien partly for her pregnancy and made use of the opportunity to paint her infant boy.[4]

|

|

|

Van Gogh reached a point around 1885 when he was looking to free himself physically, emotionally and artistically from the gray colors of his art and life, moving away from Nuenen to develop, as author Albert Lubin describes, a more "imaginative, colorful art that suited him much better."[14]

Parisian influences

In 1886, Van Gogh left the Netherlands never to return. He moved to Paris to live with his brother Theo, a Parisian art dealer. Van Gogh entered Paris as a shy, somber man. While his personality would never change, he emerged artistically into what one critic described as a "singing bird".[15] Although Van Gogh had been influenced by his cousin Anton Mauve and the Hague School, as well as the great Dutch masters, coming to Paris meant that he was exposed to Impressionism, Symbolists, Pointillists, and Japanese art (see Japonism). His circle of friends included Camille Pissarro, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Gauguin, Émile Bernard, Paul Signac, and others. The works of the Japanese printmakers Hiroshige and Hokusai greatly influenced Van Gogh, both for the subject matter and the style of flat patterns of colors without shadow. In the two years from 1886 through 1888 he spent working in Paris, Van Gogh explored the various genres, creating his own unique style.[15]

Arles

Van Gogh moved to Arles in southern France where he produced some of his best work. His paintings represented different aspects of ordinary life, such as portraits of members of the Roulin family and La Mousmé. The sunflower paintings, some of the most recognizable of Van Gogh's paintings, were created in this time. He worked continuously to keep up with his ideas for paintings. This is likely one of Van Gogh's happier periods of life. He is confident, clear-minded and seemingly content.[16]

In a letter to his brother, Theo, he wrote, "Painting as it is now, promises to become more subtle - more like music and less like sculpture - and above all, it promises color." As a means of explanation, Vincent explains that being like music means being comforting.[16]

Van Gogh painted the family of postman Joseph Roulin in the winter of 1888, every member more than once.[17] The family included Joseph Roulin, the postman, his wife Augustine and their three children. Van Gogh described the family as "really French, even if they look like Russians."[18] Over the course of just a few weeks, he painted the Augustine and the children several times. The reason for multiple works was partly so that the Roulin's could have a painting of each family member, so that with these pictures and others, their bedroom became a virtual "museum of modern art." The family's consent to modeling for Van Gogh also gave him the opportunity to create more portraits, which was both meaningful and inspirational to Van Gogh.[19]

Van Gogh used color for the dramatic effect. Each family member clothes are bold primary colors and van Gogh used contrasting colors in the background to intensify the impact of the work.[3]

Augustine and Marcelle Roulin

In Philadelphia Museum of Art's Portrait of Madame Augustine Roulin and Baby Marcelle Augustine holds baby Marcelle who was born in July, 1888. The mother, relaxed and her face in a shadow, is passive. We can see by the size of Augustine's sloping shoulders, arm, and hands that she worked hard to take care of her family. For instance, there were no modern conveniences like washing machines. In a traditional pose of mothers and new babies, Augustine is holding her baby upright, supporting the baby's back by her right arm and steadying the baby's midsection with her left hand. Marcelle, whose face is directed outward, is more active and engages the audience. Van Gogh used heavy outlines in blue around the images of mother and baby.[3]

To symbolize the closeness of mother and baby, he used adjacent colors of the color wheel, green, blue and yellow in this work. The vibrant yellow background creates a warm glow around mother and baby, like a very large halo. Of his use of color, Van Gogh wrote: "instead of trying to reproduce exactly what I have before my eyes, I use color... to express myself more forcibly." The work contains varying brushstrokes, some straight, some turbulent - which allow us to see the movement of energy "like water in a rushing stream." Émile Bernard, Van Gogh's friend, was the initial owner of this painting in its provenance.[3]

Marcelle Roulin

Marcelle Roulin, the youngest child, was born on 31 July 1888, and four months old, when Van Gogh made her portraits.[20] She was painted three times by herself and twice on her mother’s lap.[17] The three works show the same head and shoulders image of Marcelle with her chubby cheeks and arms against a green background.[21] When Johanna van Gogh, pregnant at the time, saw the painting, she wrote: "I like to imagine that ours will be just as strong, just as beautiful – and that his uncle will one day paint his portrait!"[17] A version titled Roulin's Baby resides at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.[22]

In addition to the mother-daughter works where Marcelle is visible, Van Gogh also created several works where Augustine rocked her unseen cradle by a string.[4]

Camille Roulin

Camille Roulin, the middle child, was born in Lambesc in southern France, on 10 July 1877, and died on 4 June 1922. When his father had to answer to letters, he served as his secretary.[20][23] When his portrait was painted, Camille was eleven years of age. The Van Gogh Museum painting[18] shows Camille's head and shoulders. Yellow brush strokes behind him are evocative of the sun.[24] The very similar painting resides at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (F537).[25]

In The Schoolboy with Uniform Cap Camille seems to be staring off in space. His arm is over the back of a chair, mouth gaped open, possibly lost in thought. This was the larger of the two works made of Camille.[24]

Armand Roulin

Armand Roulin, the eldest son, was born on 5 May 1871 in Lambesc, and died on 14 November 1945. He was 17 years of age when portrayed by Van Gogh.[26]

Van Gogh's works depict a serious young man who at the time the paintings were made had left his parents’ home, working as a blacksmith's apprentice.[27] The Museum Folkwang work depicts Armand in what are likely his best clothes: an elegant fedora, vivid yellow coat, black waistcoat and tie.[24][27] Armand's manner seems a bit sad, or perhaps bored by sitting.[24] His figure fills the picture plane giving the impression that he is a confident, masculine young man.[27]

The second work, with his body slightly turned aside and his eyes looking down, appears to be a sad young man.[27] Even the angle of the hat seems to indicate sadness. Both museum paintings were made on large canvas, 65 x 54 cm.[24]

La Mousmé

La Mousmé also known as La Mousmé, Sitting in a Cane Chair, Half-Figure (with a branch of oleander) was painted Van Gogh in 1888 while living in Arles, which Van Gogh dubbed "the Japan of the south". Retreating from the city, he hoped that his time in Arles would evoke in his work the simple, yet dramatic expression of Japanese art.[2][28] Inspired by Pierre Loti's novel Madame Chrysanthème and Japanese artwork, Vincent painted La Mousmé, a well-dressed Japanese girl. He wrote in a letter to his brother: "It took me a whole week...but I had to reserve my mental energy to do the mousmé well. A mousmé is a Japanese girl—Provençal in this case—twelve to fourteen years old."[2][28]

Van Gogh's use of color is intended to be symbolic. The audience is drawn in by his use of contracting patterns and colors that bring in an energy and intensity to the work. Complementary shades of blue and orange, a stylistic deviation from colors of Impressionist paintings that he acquired during his exploration in Paris, stand out against the spring-like pale green in the background. La Mousmé's outfit is a blend of modern and traditional. Her outfit is certainly modern. The bright colors of skirt and jacket are of the southern region of Arles. Regarding Van Gogh's painting of her features, his greatest attention is focused on the girls face, giving her the coloring of a girl from Arles, but with a Japanese influence. The young lady's posture mimics that of the oleander. The flowering oleander, like the girl, is in the blossoming stage of life.[2][28]

Girl with Ruffled Hair (The Mudlark)

Another painting from this time Girl with Ruffled Hair (The Mudlark) resides at Musée des Beaux-Arts, La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland (F535).[29]

Saint-Rémy

In May 1889 Van Gogh voluntarily entered the Saint-Paul asylum[30][31] near Saint-Rémy in Provence.[32] There Van Gogh had access to an adjacent cell he used as his studio. He was initially confined to the immediate asylum grounds and painted (without the bars) the world he saw from his room, such as ivy covered trees, lilacs, and irises of the garden.[30][33] Through the open bars Van Gogh could also see an enclosed wheat field, subject of many paintings at Saint-Rémy.[34] As he ventured outside of the asylum walls, he painted the wheat fields, olive groves, and cypress trees of the surrounding countryside,[33] which he saw as "characteristic of Provence." Over the course of the year, he painted about 150 canvases.[30]

First Steps

First Steps is one of twenty-one paintings that Van Gogh made in Saint-Rémy that were "translations" of the work of Jean-François Millet. He used black and white images of prints, reproductions or photographs to "pose as subject" and then "improvised color on it." This source of the image for this work, made January 1890, was a photograph of Millet's First Steps painting.[35]

Theo had sent the photograph of Millet's First Steps with perfect timing. Theo's wife, Jo, was pregnant with their child, so it had special meaning to the family. In addition Van Gogh was still saddened by recent seizure episodes that impacted his mental clarity. Rather than vibrant colors, here he used softer shades of yellow, green and blue. The picture depicts the father, having put down his tools, holding his arms outstretched for his child's first steps. The mother protectively guides the child's movement.[36]

Evening: The Watch

Like the painting First Steps, the painting Night or Evening: The Watch depicts happy life of a rural family: father, mother and child. Here the image seems bathed in yellow light like that of the Holy Family.[37] A lamp casts long shadows of many colors on the floor of the humble cottage. The painting includes soft shades of green and purple. The work was based on a print by Millet from his series, the four times of day.[38]

Van Gogh Museum says of Millet's influence on Van Gogh: "Millet's paintings, with their unprecedented depictions of peasants and their labors, mark a turning point in 19th-century art. Before Millet, peasant figures were just one of many elements in picturesque or nostalgic scenes. In Millet's work, individual men and women became heroic and real. Millet was the only major artist of the Barbizon School who was not interested in 'pure' landscape painting."[39]

Theo wrote Van Gogh: "The copies after Millet are perhaps the best things you have done yet, and induce me to believe that on the day you turn to painting compositions of figures, we may look forward to great surprises."[40]

Auvers-sur-Ouise

After leaving the south of France, Van Gogh's brother, Theo and artist Camille Pissarro developed a plan for Van Gogh to go to Auvers-sur-Oise with a letter of introduction for Dr. Paul Gachet,[41] a homeopathic physician and art patron who lived in Auvers.[42] Van Gogh had a room at the inn Auberge Ravoux in Auvers[43] and was under the care and supervision of Dr. Gachet with whom he grew to have a close relationship, "something like another brother."[43]

For a time, Van Gogh seemed to improve. He began to paint at such a steady pace, there was barely space in his room for all the finished paintings.[15] From May until his death on July 29, Van Gogh made about 70 paintings, more than one a day, and many drawings.."[44] Van Gogh painted buildings around the town of Auvers, such as The Church at Auvers, portraits, and the nearby fields.[43]

Portraits of Little Children

Two Young Girls, also called Two Children is owned by Musée d'Orsay, Paris.[45] Another version of Two Children is part of a private collection (F784).[46]

|

|

|

The Little Arlesienne

The Little Arlesienne (Head of a Girl) is found at the Kröller-Müller Museum.[47]

Young Man with Cornflower

The Young Man with Cornflower was made in June, 1890 in Auvers.[48]

Adeline Ravoux

During his time in Auvers, Van Gogh rented a room at the inn of Arthur Ravoux, whose sixteen-year-old daughter sat for three paintings. Van Gogh depicts Adeline, rather than a photographic resemblance, with "impassioned aspects" of contemporary life through the "modern taste for color."[49] Van Gogh wrote to his brother: “Last week I did a portrait of a girl about sixteen, in blue against a blue background, the daughter of the people with whom I am staying. I have given her this portrait, but I made a variation of it for you, a size 15 canvas."[50]

Adeline Ravoux was asked sixty-six years later what she remembered of Van Gogh. Before he painted her portrait, van Gogh had only made polite exchanges of conversation with Adeline. One day, though, he asked her if she would be pleased if he were to do her portrait. After obtaining her parents permission, she sat one afternoon in which he completed the painting. He smoked continually on his pipe as he worked, and thanked her for sitting very still. She was very proud to sit for the painting she described as a "symphony in blue". Van Gogh thought she was sixteen, but she was just thirteen years of age at the time. Adeline sat just once, but three paintings were made of her:[50]

- For the sitting, Adeline was dressed in a blue dress, the background was blue and her hair ribbon was blue.

- Van Gogh made a copy of the original painting for his brother, with slightly different shades of blue.

- In a slightly different pose or aspect, Adeline appears against a background of roses, portions of a still life of roses (F595) that he completed just a few days prior to this painting. This painting is owned by the Cleveland Museum of Art.[50]

Neither she nor her parents appreciated Van Gogh's style and were disappointed that it was not true to life.[50] Yet, even though Adeline was a young girl at the time, pictures of her as a young woman showed that van Gogh painted her as she would become.[1]

|

|

|

See also

List of works by Vincent van Gogh

References

- ^ a b c Cleveland Museum of Art (2007). Monet to Dalí: Impressionist and Modern Masterworks from the Cleveland Museum of Art. Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-940717-89-3.

- ^ a b c d "La Mousmé". Postimpressionism. National Gallery of Art. 2011. Archived from the original on May 10, 2011. Retrieved March 20, 2011Additional information about the painting is found in the audio clip.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b c d "Portrait of Madame Augustine Roulin and Baby Marcelle". Collections. Philadelphia Museum of Art. 2011. Retrieved April 13, 2011Additional information in "Teacher Resources" and audio clip.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b c Lubin, A (1996) [1972]. Stranger on the Earth: A Psychological Biography of Vincent van Gogh. Da Capo Press. p. 15. ISBN 0-306-80726-2.[permanent dead link]

- ^ van Gogh, V, van Heugten, S, Pissarro, J, Stolwijk, C (2008). Van Gogh and the Colors of the Night. Brusells: Mercatorfonds with Van Gogh Museum and Museum of Modern Art. pp. 12, 25. ISBN 978-0-87070-736-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wallace, R (1969). The World of Van Gogh (1853-1890). Alexandria, VA, USA: Time-Life Books. pp. 10, 14, 21, 30.

- ^ van Gogh, G, Bassil, A (2004). Vincent Van Gogh. Milwaukee, WI: World Almanac Library. p. 24. ISBN 0-8368-5602-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gayford, M (2008) [2006]. The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Nine Turbulent Weeks in Provence. Mariner Books. pp. 195–196. ISBN 978-0-618-99058-0.

- ^ "Boy Cutting Grass with a Sickle". Van Gogh Gallery. 2011. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ "Girl in a wood". Collection. Kröller-Müller Museum. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ van Gogh, V (2011). Harrison, R (ed.). "Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, The Hague, 20 August 1882". Letters of Vincent van Gogh. van Gogh, J (trans.). WebExhibits. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- ^ Lubin, A (1996) [1972]. Stranger on the Earth: A Psychological Biography of Vincent van Gogh. Da Capo Press. pp. 5–6. ISBN 0-306-80726-2.

- ^ "Van Gogh Paintings". Van Gogh Gallery. 2011. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ Lubin, A (1996) [1972]. Stranger on the Earth: A Psychological Biography of Vincent van Gogh. United States: Da Capo Press. pp. 74–75. ISBN 0-306-80726-2.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c Wallace, R (1969). The World of Van Gogh (1853-1890). Alexandria, VA, USA: Time-Life Books. pp. 40, 69.

- ^ a b Morton, M; Schmunk, P (2000). The Arts Entwined: Music and Painting in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Garland Publishing. pp. 177–178. ISBN 0-8153-3156-8.

- ^ a b c "Portrait of Marcelle Roulin, 1888". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Archived from the original on May 16, 2013. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ a b "Portrait of Camille Roulin, 1888". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ Gayford, M (2008) [2006]. The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Nine Turbulent Weeks in Provence. Mariner Books. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-618-99058-0.

- ^ a b Letter xxx

- ^ Gayford, M (2008) [2006]. The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Nine Turbulent Weeks in Provence. Mariner Books. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-618-99058-0.

- ^ "Roulin's Baby". The Collection. National Gallery of Art. 2011. Archived from the original on May 8, 2009. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ Letter of Joseph Roulin to Vincent van Gogh, 24 October 1889; see Van Crimpen & Berends-Alberts (1990), pp. 1957-58 (Nr. 816) - see previous note.

- ^ a b c d e Gayford, M (2008) [2006]. The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Nine Turbulent Weeks in Provence. Mariner Books. pp. 213–214. ISBN 978-0-618-99058-0.

- ^ "Portrait of Camille Roulin". Collections. Philadelphia Museum of Art. 2011. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ Letters of Joseph Roulin to Vincent van Gogh, 22 May and 24 October 1889; see Van Crimpen, Han & Berends-Alberts, Monique: De brieven van Vincent van Gogh, SDU Uitgeverij, The Hague 1990, pp. 1878-79 (No. 779); 1957-58 (Nr. 816) - both letters, written in French, are hitherto only published in Dutch translation.

- ^ a b c d Zemel, C (1997). Van Gogh's Progress: Utopia, Modernity, and Late-Nineteenth-Century Art. University of California Press. pp. 108–110. ISBN 9780520088498.

- ^ a b c Jessup, ed. (2001). "Van Gogh in the South". Antimodernism and Artistic Experience. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 185. ISBN 0-8020-8354-4.

- ^ "Girl with Ruffled Hair (The Mudlark)". Van Gogh Gallery. 2011. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". Thematic Essay, Vincent van Gogh. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2000–2011. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ^ "Olive Trees, 1889, Van Gogh". Collection. Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ^ "Olive Trees, 1889, van Gogh". Collection. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2000–2011. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ^ a b "The Therapy of Painting". Van Gogh Museum. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ^ Van Gogh, V & Leeuw, R (1997) [1996]. van Crimpen, H & Berends-Albert, M. (eds.). The Letters of Vincent van Gogh. London and other locations: Penguin Books. p. F604.

- ^ "Vincent van Gogh: First Steps, after Millet". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. December 2008. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ Maurer, N (1999) [1998]. The Pursuit of Spiritual Wisdom: The Thought and Art of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin. Cranbury: Associated University Press. p. 99. ISBN 0-8386-3749-3.

- ^ Zemel, C (1997). Van Gogh's Progress: Utopia, Modernity, and Late-Nineteenth-Century Art. University of California Press. p. 17. ISBN 9780520088498.

- ^ "Night (after Millet), 1889". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ "Jean-François Millet". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ Harrison, R (ed.). "Theo van Gogh. Letter to Vincent van Gogh. Written 3 May 1890 in Saint-Rémy". van Gogh, J (trans.). WebExhibits. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- ^ Wallace, R (1969). The World of Van Gogh (1853-1890). Alexandria, VA, USA: Time-Life Books. pp. 162–163.

- ^ Strieter, T (1999). Nineteenth-Century European Art: A Topical Dictionary. Westport: Greenwood Press. p. 17. ISBN 0-313-29898-X.

- ^ a b c Leeuw, R (1997) [1996]. The Letters of Vincent van Gogh. London and other locations: Penguin Group. pp. 488, 490, 491. ISBN 9780140446746.

- ^ "Girl in White, 1890". The Collection. National Gallery of Art. 2011. Archived from the original on August 30, 2016. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- ^ "Two Fillettes (Two Young Girls)". Index of Works. Musée d'Orsay. 2006. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ "Two Children". Van Gogh Gallery. 2011. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ "Portrait of a Young Woman". Collection. Kröller-Müller Museum. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ "Young Man with Cornflower". Van Gogh Paintings. Van Gogh Gallery. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- ^ "Adeline Ravoux". Collections Online. Cleveland Museum of Art. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Leaf, A; Lebain, F (2001). Van Gogh's Table: At the Auberge Ravoux. New York: Artisan. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-1-57965-315-6.

External links

![]() Media related to Paintings of children, Vincent van Gogh serie at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Paintings of children, Vincent van Gogh serie at Wikimedia Commons

- Paintings of Arles by Vincent van Gogh

- Paintings of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence by Vincent van Gogh

- Paintings of Auvers-sur-Oise by Vincent van Gogh

- Series of paintings by Vincent van Gogh

- 19th-century portraits

- 1888 paintings

- 1889 paintings

- 1880s paintings

- 1890s paintings

- Collections of the Van Gogh Museum

- Paintings of children