Classical Greek sculpture

Classical Greek sculpture has long been regarded as the highest point in the development of sculptural art in Ancient Greece, becoming almost synonymous with "Greek sculpture". The Canon, a treatise on the proportions of the human body written by Polykleitos around 450 B.C., is generally considered its starting point, and its end marked with the conquest of Greece by the Macedonians in 338 B.C., when Greek art began a great diffusion to the East, from where it received influences, changed its character, and became cosmopolitan. This phase is known as the Hellenistic period. In this period, the tradition of Greek Classicism was consolidated, with Man being the new measure of the universe.

The sculpture of Classicism developed an aesthetic that combined idealistic values with a faithful representation of nature, while avoiding overly realistic characterization and the portrayal of emotional extremes, generally maintaining a formal atmosphere of balance and harmony. Even when the character is immersed in battle scenes, their expression shows to be hardly affected by the violence of the events.[1][2]

Classicism raised Man to an unprecedented level of dignity, at the same time as it entrusted him with the responsibility of creating his own destiny, offering a model of harmonious life, in a spirit of comprehensive education for an exemplary citizenship. These values, together with their traditional association of beauty with virtue, found in the sculpture of the Classical period with its idealized portrait of the human being, a particularly apt vehicle for expression, and an efficient instrument of civic, ethical and aesthetic education. With it, a new form of representation of the human body - influential to this day - began, being one of the cores of the birth of a new philosophical branch, Aesthetics, and the stylistic foundation of later revivalist movements of importance, such as the Renaissance and Neoclassicism. Thus, Classicism had an enormous impact on Western culture and became a reference for the study of Western art history. Apart from its historical value, Classicism's intrinsic artistic quality has had great impact, the vast majority of ancient and modern critics praising it vehemently, and the museums that preserve it being visited by millions of people every year. The sculpture of Greek Classicism, although sometimes the target of criticism that relates its ideological basis to racial prejudices, aesthetic dogmatism, and other particularities, still plays a positive and renovating role in contemporary art and society.[3][4][5]

Definition of "classic"

The word "classical" has wide usage, and there is yet no consensus in specialized literature regarding its exact definition. The Greek and Roman civilizations have been called classical in their entirety for having established cultural standards that have become canonical and are valid today. The term is still used with a stricter meaning, to refer to a brief period within the long history of ancient Greek culture – from the mid-5th century to almost the end of the 4th century BC. – when a style that for many centuries would be considered the highest achievement in the art of sculpture developed, earning the designation of classic.[6][note 1]

Context and background

Classicism in Greek sculpture derives mainly from the Athenian cultural evolution in the 5th century B.C. In Athens, the main artistic figure was Phidias, but Classicism owes an equally important aesthetic contribution to Polykleitos, active in Argos. However, in those times Athens was a much more influential city, hence its greater role as a diffuser of the new trend. Around the middle of the 5th century B.C., Greece was experiencing a moment of glory; after the victory against the Persians, Athens had assumed the leadership of the Greek cities, heading the Delian League and being the custodian of its treasury.

Pericles dominated local politics between 460 and 429 B.C., aiming to turn the city into a model for the entire Greek world. He encouraged imperialism, reducing his former allies to the status of tributaries, but protected artists and philosophers, who gave shape and voice to his ideals. His role in the history of Greek sculpture stems from his decision to rebuild the city by breaking a vow made by the Athenians to leave in ruins the monuments that had been destroyed by the Persians, as a perennial reminder of barbarism. Using partly his own resources and partly the surpluses from the League's treasury, Pericles employed a multitude of laborers and craftsmen, which both energized the economy and left a monumental testimony to the city's new political and cultural status. The main legacy of the vast undertaking was the renovation of the Acropolis of Athens, with Phidias as the artistic director of the works.[7][8] Plutarch later described the enthusiasm that boiled over:

As the works went on, resplendent in grandeur and possessing inimitable grace of form, and as the craftsmen strove to surpass each other in the beauty of their work, it was wonderful how quickly the new structures were executed...There was an aspect of novelty in each work, and they seemed timeless. It is as if a life in continual bloom and a spirit of eternal youth had been infused into their creation.[9]

Philosophy shifted its focus from the natural world to human society, believing that Man could be the author of his own destiny. More than that, Man was now considered the center of Creation. Sophocles expresses this new thinking in Antigone (c. 442 BC), saying:

There are many wonders, but none so admirable as Man.

Across the stormy sea in the winter storms

this creature makes their way

through the gigantic waves.

And the earth, the most ancient of goddesses,

the one that is immortal and immune to old age, he works

plowing back and forth, year after year

turning the soil with the horses it has fed. (...)

"With his inventions he subdues the fierce beasts of the mountains,

the wild horse he muzzles and puts a halter on,

as he does with the indefatigable mountain bull.

He taught himself language, swift as the wind,

and learned for himself how to live in society,

how to escape from the impetus of the storms

and the piercing cold of the white days.

He can face anything, he is never unprepared,

whatever the future brings. Only from death he doesn't know how to escape,

for even for the most serious illnesses, he has found a cure.[10]

Thus, Classicism was born out of a sense of confidence in the abilities and achievements of a particular people, and a desire for glory and eternity for themselves. This pride can be seen in the political discourse and literature of the time, and poets and philosophers were already aware of the implications of this new way of seeing the world. Man became the new measure of the world, which was to be judged based on human experience. This is present, for example, in the mathematical irregularity of the Parthenon's dimensions, which deviate from strict orthogonality to achieve effects of purely optical regularity. It is also expressed in the rapid and growing naturalism of the sculptural representation of human forms.[11][12]

Regarding the elaboration of the typical classical form itself, its naturalism owes much to the achievements of sculptors of the period preceding the Classical. The previous fifty years had been a period of a rapid radical social and aesthetic change, which determined the abandonment of the Archaic pattern for another which was called Severe. The Archaic style made use of several conventions inherited from the Egyptians, and its most important genre, the male nude (the kouros) had a fixed formula: An image of stylized lines that retained from the real human body only the most basic features, that displayed an invariably smiling face and the same bodily attitude.

This model prevailed with little variation for more than two hundred years, but the artists of the Severe period introduced a new sense of naturalism to it, opening the way for the study of anatomy and for the expression of emotions in a more realistic and varied way. Around 455 B.C., Myron, a sculptor of the transition, created his Discobolus, a work that already shows a more advanced degree of naturalism, and soon after, around 450 B.C., Polykleitos consolidated a new canon of proportions, a synthesis that convincingly expressed the beauty, harmony and vitality of the body and gave it an aspect of eternity and perennial youth. Almost at the same time, in 446 B.C. Phidias, leading the group of sculptors decorating the Acropolis, left in the reliefs and statuary of the Parthenon the first series of classicist works on a monumental scale, establishing thematic and narrative models that would endure for a long time. With them, the foundations for the sculpture of what is called High Classicism (c. 450-420 B.C.) were laid.[13][14][8][1]

High Classicism

Since the Severe period, the effort of artists was directed towards obtaining an increasing verisimilitude of sculptural forms concerning the living model but also seeking to transcend mere likeness to express their inner virtues. For the ancient Greeks, physical beauty was identified with moral perfection, in a concept known as kalokagathia. According to this, the education and cultivation of the body were as important as the improvement of the character, both being essential for the formation of a happy individual and an integrated citizen useful to society. In this philosophical panorama, which found expression in a highly organized educational model known as paideia, art had a privileged space as a creator of symbols with educational potential, being understood as a public utility activity. Since art had the function to educate rather than only please, the man it represented had to look good, virtuous, and beautiful, so that such qualities, visibly enshrined in countless statues, would permeate the collective consciousness and determine the adoption of a healthy, harmonious, and positive way of life, ultimately ensuring the happiness of all. The fusion of naturalism with idealism, typical of Classicism sculpture, a fusion so successful and influential that came to be called "classical" (in the sense of being the ultimate model), was, in short, a suitable channel for the artistic manifestation of the dominant ideology.[15][16][17]

An important contribution that crystallized the association between art and ethics was given in the Archaic period by Pythagoras, based on his research in the field of mathematics applied to music and psychology. Considering that the various musical genres impressed the soul in different ways and were able to induce psychological states and defined behaviors, according to him, if music did not imitate the mathematically expressed harmony of the cosmos, it could cause disturbances in people's souls and thus in society as a whole. This association was soon expanded to the other arts, attributing to them similar powers of individual and, consequently, collective transformation. His thought would have a profound influence on Plato's, who would take the aesthetic discussion even further, thoroughly exploring its moral and social repercussions.[18]

Polykleitos and Phidias

Polykleitos was, as far as is known, the first to systematize these values and concepts applied to sculpture in a theoretical work, the Canon. In it, the author showed a model of representation that was ideally beautiful and "real"; ideal as it avoided individual characterization by synthesizing all men into one, and real because it was very similar to the true human form, allowing immediate and personal identification by the audience. The work has been lost, but later commentaries on it demonstrate the idea of its content. Galen stated that according to the Canon, beauty:[19]

It does not lie in the symmetry of the elements of the body, but in the adequate proportion between the parts, as for instance, from one finger to another finger, from the fingers together to the hands and wrist, from these to the forearm, from thence to the arm, and from all to all, just as it is written in the Canon of Polykleitos. Having taught us in this treatise all the symmetries of the body, Polykleitos ratified the text with a work, having made a statue of a man according to the postulates of his treatise, and calling the statue, like the treatise, the Canon. Since then, all philosophers and doctors accept that beauty lies in the adequate proportion of the parts of the body.[19]

The statue Galen speaks of is today identified as likely being the Doryphoros,[15] and Arnold Hauser has suggested, almost without objection, that it represents Achilles.[20] Andrew Stewart mentions that the author's intention with it was to polemicize, criticizing the style of predecessors like Pythagoras – not to be confused with the philosopher – who were more concerned with symmetry and rhythm. His neutral and dispassionate expression, his balance between staticity and movement (the contrapposto), his care in establishing a strict system of proportions that defined the whole composition of the body figure and the relations of the parts to each other, appeared as a great novelty in his time. It represented a perfect visible illustration of Sophrosyne, self-control, and moderation, one of the basic virtues that made up arete, and the Apollonian doctrine of "nothing in excess", which characterized the true hero. Although highly appreciated, Polykleitos' system, however, was not approved for all cases. Its unsuitability for narrative and violent contexts such as battle scenes was criticized, and writers such as Quintilian later said that this system failed to express the authority of the gods, which may reflect an older opinion. Even so, the success of the model is evidenced by the large number of times it was copied and its profound influence on later generations. Modern writers have also found analogies between Doryphoros' balance (based on a delicate balance of opposing forces) and Hippocrates' formulations of medicine, and therefore believe that the famous physician's thinking was deliberately assimilated by the sculptor.[21][22][23]

Polykleitos may have been inspired by the earlier research on proportions by the sculptor Pythagoras. Still, his ideas were part of his contemporaries' quest to discover the regular and harmonious structure (the basic model) underlying the infinite variations of the same kind of thing in the physical world and to establish definite numerical relationships to replicate this regularity and harmony in art, continuing the philosopher Pythagoras' theory that the universe was structured by numbers. Two other of his compositions are now also called "canonical": The Discophoros and the Diadumenos, as they are variations of the basic model.[24]

As for Phidias, his work inherited the austerity of the Severe style by combining it with the achievements of Polykleitos, and was appreciated for the high idealism and ethos it expressed. As director of the decoration of the Parthenon, he supervised a group of several masters with diverse preparation and tendencies, which made the overall result heterogeneous, showing both Severe and other more advanced, naturalistic traits, and technical quality not always considered the ideal one. This ensemble is the most ambitious sculptural achievement of High Classicism.

Phidia's success among his contemporaries and his enduring memory derive mainly from his colossal cult statues of Athena and Zeus, which used to be installed respectively in the Parthenon in Athens and the temple of Zeus in Olympia. Both were covered with gold and ivory and had a huge impact at the time. Of the Statue of Zeus at Olympia, considered one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world, only literary descriptions and crude images engraved on coins of the time remain. But of the Athena Parthenos, created in 438 B.C., several reduced copies of poorer quality survived. Other works that persevered through copies and are attributed to him, without much assurance, are the Lemnian Athena, the Apollo of Cassel, a wounded Amazon, and a Hermes Ludovisi.[25][26][27]

Other sculptors working around Polykleitos' proposal in the period of High Classicism are Alcamenes, Kresilas, and Paeonius. Callimachus, a master greatly appreciated for the refinement of his works, is regarded as the inventor of the Corinthian capital, and Calamis, another relevant name, was Phidias' assistant and is credited with the design of the Parthenon metopes. However, his style still carried some influence from the Severe period, of which he was one of the greatest representatives.[obsolete source]

Arete x pathos in artistic mimesis

The impersonal, balanced, and austere style of Polykleitos and Phidias, which typifies High Classicism, did not last for long. In his Memorabilia, Xenophon left more information about the state of art criticism in the transition to Late Classicism. In the text, which recalls Socrates' career, it is shown that at this time there was a debate about the capabilities and limits of mimesis (imitation). He argues with Kleitos – an unknown sculptor whom some consider to be Polykleitos – saying that his statues of winning athletes should show not only an ideal of beauty but also what was happening in the psyche, the soul. The interpretation of this passage is controversial but it raises a question about the relationship between appearances and truth, and admits the possibility of art expressing pathos, individual emotion, and drama, in direct opposition to the neutrality and restraint of Polykleitos. For an audience used to seeing in celebratory statues, not a tribute to the individual who served as a model, but a portrait of collective heroism, an example to be followed by all citizens and a service rendered to the whole society, this concept came as a shock, weakening the absolute and invariable character of arete.[28][29] Regarding the problem of the imitative representation of nature in art, Stephen Halliwell says:

Even within the confines of the conversations reported by Xenophon in the Memorabilia, we can discern a tension – a tension that would become central to the entire legacy of mimesis – between divergent views on representational art being, on the one hand, a fictional illusion, the product of a 'deceptive' artifact, and, on the other, a reflection of and an engagement with reality.[30]

This paradox announced the end of the primacy of the ideal. The individual sphere of interest became increasingly important, which would be the essence of the art of the 4th century B.C., when Plato and Aristotle would extraordinarily deepen what Socrates had outlined, laying the foundations for the development of an entirely new philosophical branch: Aesthetics.[31]

-

Callimachus: Venus, Roman copy, Louvre.

-

Phidias Workshop: Dionysus, original. Formerly on the pediment of the Parthenon, now in the British Museum.

-

Varvakeion Athena, reduced copy of Phidias' Athena Partheno, originally in the Parthenon. National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

-

Possibly designed by Calamis: Southern metope of the Parthenon, original. British Museum.

-

Monument to the Nereids, original. British Museum.

Low Classicism

By the end of the 5th century B.C., Athens' hegemony was in decline, weakened by internal unrest and external wars, and soon Sparta, Corinth, and Thebes became prominent. However, at the beginning of the 4th century B.C., Athens regained some of its power and prestige, restored its democracy and its wealth grew again. Even so, politics became more and more complex, having developed what is called the "state apparatus," and the polis lost its communitarian character. At the same time, Greek colonies around the Mediterranean multiplied, some achieving great development, with diversified and profitable economies that imitated the social model of the metropolitan polis. The decentralization of culture throughout these regions and the rise of a wealthy merchant class, consumers of art but with its own values, opened the way for the appreciation of individual taste and the influence of foreign cultural elements, dissolving the rigidity and austerity of High Classicism.[32][33]

In sculpture, the concern with verisimilitude became even more pronounced. Innovations in the stone carving technique allowed greater control in the finishing of details, in the representation of robes and dresses, and in the polishing of surfaces to obtain subtle effects of light and shadow. The sculptors of the new generation introduced a general relaxation of Polykleitos' canon, developing a new repertoire of more dynamic attitudes of the body and setting aside the mathematically established proportions to create images convincing to the senses, more similar to real world bodies with their physical idiosyncrasies and personal affections. Thus began the period called Lower Classicism, or Late Classicism.

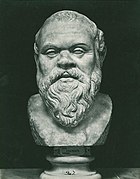

The statues acquire an even more emphatic "presence", also a result of new detailed and realistic treatment given to the face, hair and beard. The individualized portrait was born, an innovation attributed to Lysistratus, the first, according to Pliny the Elder, to make molds of the model's face. The goal was transferred from beautification to likeness, inviting the spectator to meditate on the possible discrepancies between the moral value and the external appearance. The realistic portraits of Socrates from this period, whose appearance was notorious as well as his virtue, exemplify the new dimension into which the art of bodily representation began to permeate.[34]

While the preferences of the expanding market were increasingly opening up to individual taste, Plato's traditionalist and idealistic questionings of the role of mimesis in art, plus his condemnation of the tragic, raised problems for the validation of the artistic product that have not yet been fully resolved.[35][36][37] The theoretical debate in the transition to Lower Classicism was advanced by Aristotle, whose theory of catharsis contributed to the formulation of a new concept of art liberally avoiding the condemnation of popular culture and its typical emotionalism. He also defended the representation of "nonbeautiful" objects based on the assumption that ugliness in art could be a source of teaching and aesthetic pleasure, overcoming the sorrow that its contemplation in real life would cause. Still, Aristotle did not stop advising young individuals to prefer works by artists he qualified as ethical, those whose creations best exemplified good human character, because their influence would be beneficial to the entire polis.

Such ideas contributed to the fact that sculpture production continued to flourish, meeting new needs, but the closer approach to the natural did not mean a complete abandonment of the ideal. Realism as a dominant trend would only appear in Greek sculpture with the succeeding Hellenistic school. Lysippos still criticized sculptors who created works from the natural and prided himself on modeling men as they "should" be.[38][39][40][41] In the field of sacred statuary, there were also new aspects. In the myths, all mortals who saw gods in their glory died, became blind, insane, or suffered in other ways. The culture of the time was able to accept partial and imperfect representations of the gods. Even shapeless stones, trees, and places could be recognized as receptacles for the divine, and anthropomorphic cult statues could remain hidden or semi-hidden by veils, robes, and various adornments, requiring the devotee to exercise spiritual contemplation that did not require likeness to take place, although it might be facilitated by an idol that looked beautiful or majestic, or that more directly evoked the attributes of the god.

However, thinkers like Plato considered the anthropomorphization of a deity to be unbecoming and misleading, as it not only misrepresented its object but also demeaned it in an attempt to bring it too much into the sphere of the human. To face these difficulties, later sculptors made use of special resources to keep the distance between gods and men clear, rescuing archaic stylistic traits such as frontality, hieratic posture, impassive and supernatural features, which, in contrast to the increasingly naturalistic and expressive style of profane statuary, delimited well the spheres of the sacred and the mundane and forced the devotee to respect the idol, as a reminder that the divine remains forever essentially unknowable. When the representation of the deities was not directly linked to the cult, as in monuments and decorative architectural reliefs, there was greater formal freedom, although some of the same conventions were observed and an attempt was made to maintain traits that well identified the divine aspect of the character.[42][43][44]

The emphasis on naturalism in statues also gave rise to consequences in the affective realm. It was not unusual that in their function as stand-ins for a person or a god, statues were the object of intense love, which could lead to the desire to get emotional and/or sexual gratification from the statues. From Pandora to Pygmalion, myths relate various intimate interactions of statues with humans, and historical records show that mortals could also fall into the temptation to seek from the simulacra. Aristophanes warned against the risk of humans giving in to passions in front of statues or becoming too attached to them, and being condemned to live as the living dead nurturing an ever-incomplete love, although he considered that from the inevitable frustration could be born the opportunity for the individual to discover themselves.[45]

Praxiteles, Scopas and Lysippos

Greek sculpture of the 4th century B.C. was dominated by three great figures: Praxiteles, Scopas and Lysippos. Praxiteles is likely to have been the first to fully explore the sensual possibilities of marble. The erotic appeal of his Aphrodite of Knidos – the first completely nude female statue in Greek art – made her famous in her day and gave rise to the prolific typological family of the Venus Pudica. His Hermes and the Infant Dionysus illustrates his mastery in depicting the facial expression and grace of flexible, sinuous bodies.

Scopas became known for the sense of drama, violence, dynamism, and passion with which he imbued his works, especially those he left in the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, the most important Greek architectural achievement in this period, although in others he showed his ability to portray tranquility and harmony. Lysippos reformulated the Polykleitos canon by reducing the dimensions of the head and making the figure more elongated, though more massive. He is also credited with the first statue whose finish was carried out equally in all directions, the Apoxiomenon, enabling the viewer to appreciate it not only from a single, privileged point of view, as was still the use of Polykleitos.

These masters, along with other notable figures of their generation such as Leochares, Bryaxis, Cephisodotus the Elder, Euphranor, and Timotheus, resolved all outstanding basic difficulties regarding form and technique that might still hinder the free expression of the idea in matter. Thus, they contributed with great achievements in the process of exploring human anatomy, the representation of clothing, and solving problems of composition, being the link in the passage from the classical to the Hellenistic tradition, as well as bringing the technique of stone carving and bronze modeling to an unprecedented level of quality. The following generations would have little to add to the essence of classical art, but would deepen their research into the portrayal of the emotional and the prosaic, bringing marble sculpture to a level of true technical virtuosity.[32][46][47]

The study of the functions and meanings of classical sculpture is still progressing. The reciprocal interactions and influences at various levels that categories, uses, and attributions might have established are not fully known, and much remains to be elucidated about how representation influenced the construction of concepts and practices regarding gender, status, social inclusion, affect, sexuality, aesthetics, ideology, politics, religion, ethics, and the historical evolution of Greek society. Part of such difficulty is due to the fact that many works are only known through literary references, later copies, are in an incomplete and damaged state, or because their dating and attribution of authorship are often uncertain and the biographies of their creators have multiple gaps and inconsistencies.[48]

-

Cephisodotus the Elder: Eirene bearing Plutus, Roman copy. Munich's Glyptothek.

-

Lysippos: Apoxiomenon, Roman copy. Vatican Museums

-

Amazonomachy, frieze of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, original

-

Unknown author: Dionysius Sardanapalo, Roman copy. National Roman Museum

-

Antikythera Ephebe, original. National Archaeological Museum of Athens

-

Attributed to Praxiteles: Aphrodite of the Syracuse, Roman copy. National Archaeological Museum of Athens

-

Timothy: Leda and the Swan, Roman copy. Capitoline Museums

-

Lysippos: Eros stringing his bow, Roman copy. Capitoline Museums

Other uses and techniques

In the purely technical field, there were no radical advances in what the sculptors of the Archaic and Severe period had already achieved. The Archaic marbles already showed a very high mastery of stone, visible especially in their architectural reliefs. In the case of bronze, the main innovation in their history for Greek sculpture was the development of the lost wax technique but its principles were already masterfully handled in the Severe period, with a diversified application. Therefore, Classicism benefited from the fact that the main sculptural techniques had already been refined enough that the main interest shifted to the aspects of form and meaning, although always with some advances in refinement.[49]

Funeral sculpture

Among the uses of sculpture, was the composition of funeral monuments, where in general terms it shared the characteristics of decorative sculpture in temples and public buildings. The tradition of building monuments to the dead existed since the Archaic period when the kouros fulfilled this function. With the advent of democracy in the early 5th century B.C., customs began to change and funerary stelae – relief plaques with inscriptions – appeared.

After an irregular development, as they disappeared in some periods, in the Classic period they became a common practice in Attica, while in other regions they would only become popular in Hellenism. One of the first important stelae of Classicism is the Stela of Eufero, dated c. 430 B.C., its style showing a connection with the decorative sculpture of the Parthenon that was being created at the same time. It has been a traditional thought that such monuments were the endowment of the wealthy, but recent studies have indicated that their cost would have been much less than once thought, which means the lower classes could commission a votive plaque, although there were clear differences in luxury and sophistication between the burials of the common people and those of the great families. The museums of classical archeology exhibit a great number of specimens. Highlights are those of Late Classicism, which show portraits of the deceased together with family members in scenes sometimes of great sensitivity and poetry.[50][51]

Terracottas

Terracotta is an ancient technique; however, its application has been more common in pottery, with sculptural uses limited to decorative objects and small statuettes for popular usage, figuring actors, animals, and types of people. These had generally no great technical refinement and repeated crudely the formal principles of large sculpture. Larger and more refined pieces were rare, and would appear more often with the Hellenistic schools from the late 4th century B.C. onward. A rich artwork from Attica in the Louvre Museum is worth mentioning, suggesting advanced practices in this field already during Classicism.

Elements of terracotta in architectural decoration had great use in earlier and later periods but in Classicism rarely occurred. One type of terracotta that stands out is the statuettes with articulated limbs. This group has likely performed specific functions. They have been found in many tombs, suggesting an association with Cthonic deities. It is also speculated that they served as statues for domestic worship, as offerings to the gods, and as magical protection against evil forces. Many of them have holes in the back of their heads, indicating that they could be worn suspended, which allowed free movement of their limbs. It has been thought that they were children's dolls, but their fragility, preventing repeated handling, does not support this assumption. As for votive statues, a great syncretism of styles is observed, especially in Late Classicism, when archaic traits continue to appear in quantity, side by side with more progressive stylistic elements, following the conventions of monumental cult statuary.[52][53][54][55]

-

Terracotta statuette with articulated limbs, original. Staatliche Antikensammlungen

-

Leda and the Swan, polychrome terracotta, original, Attica school. Louvre Museum

-

Terracotta theatrical mask model, original. British Museum

-

Priapic statuette of an actor, terracotta, original. Staatliche Antikensammlungen

Goldsmithery

Goldsmithery was present as a technique of miniaturized sculpture, where there was significant production mainly in the colonies of Magna Grecia, Cyprus, and the southern Black Sea, with finds in mainland Greece being rare. Most of the jewelry of this phase is related to religious contexts, decorating cult statues, being votive offerings, or celebratory, as in the case of the gold crowns used in the apotheosis of politicians. The use of personal jewelry was not uncommon. Their quality, while high, is shown to be lower than the jewelry of the Archaic period. The motifs represented are in general abstract, animal, and vegetal, and the popularization of human forms happens at the end of the Classical period, along with the appearance of the first cameos.[56]

Copies and Color

The common practice of the ancient Greeks was to cover their statues and architectural reliefs with paint, either partially or in its entirety, seeking an even more striking resemblance than their simple form and structure could achieve. For centuries, it was thought that their works appeared to them as they do nowadays, but in reality, they were richly colored. Studies suggest that in Classicism the use of color in sculpture was more discreet than in earlier periods. Recently researchers have tried to reconstruct the polychromy of statues in specially made copies, causing fascination and surprise as the usage of color differs from the one common today.[57][58][59][49]

Of great value for reconstructing the landscape of Greek sculpture are the miniature copies, which were extremely popular and replicated in smaller scale virtually every formal model and every important work of monumental statuary, a practice that was not limited to the Classical period. Still, some very successful subjects that were copied several times in their original size are not found in miniatures, as is the case of Polykleitos' Doryphoros. It is likely that the absence of finds is due to the fact that these were loaded with such strong significance, that their reduction would have seemed inappropriate.

The materials used for miniaturization were bronze, marble, ivory, and eventually other stones. Terracotta, despite its versatility, does not seem to have been considered a worthy material for the reproduction of celebrated works, at least not during Classicism.[60]

Legacy and Perspectives

Classical art has exerted a vast influence throughout the history of the West, as shown by the consensus among specialists. The sculptural legacy of the classics continues to interest multitudes even today. The very name – "classic" – indicates the unparalleled prestige they have acquired, for in current parlance "classic" is that which establishes a measure by which other things of that kind are judged.[61]

Classical sculpture was in its origin one of the levers for the birth of Aesthetics as an autonomous branch of Philosophy. Throughout history, its formal models were used for the most varied purposes, some of high humanistic inspiration, but sometimes in opposition to that, celebrating totalitarian regimes and personalisms of various kinds, as it happened during Nazism and Fascism.

In modern appreciation, the ideology underlying the sculpture of Greek Classicism does not remain free of criticism, being said to glorify a way of life and a people to detriment of others, and the collective to detriment of the individual, suppressing the questioning of the instituted order under the appearance of homogeneity and consensus. The execution of Socrates, accused of impiety and corruption of youth, by the same society that cultivated Classicism, shows how perversion and misinterpretation can happen with the positive purposes of improvement and education of the collectivity for fuller citizenship, a purer and more harmonious life, and more advanced ethics (principles that classical sculpture illustrated well). On the other hand, the criticism points to facets of a complex and contradictory social reality that were deliberately swept away from view in the art of that period.[62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69][47]

Classicism began its spread around the world through the Greek colonies scattered all around the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. Alexander the Great took it further, reaching India. In these regions, the principles of Greek sculpture were presented to the local populations and, blending with their traditions, gave rise to stylistic interpretations that more or less successfully reproduced the metropolitan aesthetic. This eclectic and cosmopolitan synthesis was called Hellenism.[70] Ancient Rome, in turn, was another avid recipient of classical Greek culture. Its sculptors took pride in working under Greek inspiration, and by multiplying copies of Greek originals that were later lost, they were the transmitters to posterity of a significant part of the culture they imitated.[71]

From the legacy transmitted by the Romans, early Christianity drew the models for starting its own art, but after the sixth century its policy changed. Until this time, immense amounts of sculpture had survived in temples and ancient monuments, but from then on, their ubiquitous nudity began to be seen as an offense to Christian morality, as well as being condemned as diabolical cult images and bad reminders of paganism. Losing their former value, ancient works began to be destroyed. On the other hand, during the Renaissance, classical culture fell back into the elites' favor and was the core of a recovery of the dignity of the body and of purely aesthetic pleasure. Christianity itself, after proscribing for centuries the pagan sculptural heritage, recovered it, transforming and adapting it to serve it and praise the heroes of the new order: the saints and martyrs of the faith. The Renaissance conception of art largely reproduces the idea formulated by the classical philosophers.[64][63] The prestige that classical statuary knew in this period reached the borders of passion, as can be seen in this excerpt by Giovanni Pietro Bellori:

Painters and sculptors, choosing from among the most elegant beauties of the natural world, perfect the idea, and their works surpass and stand above Nature – which is the ultimate scope of these arts. [...] This is the origin of the veneration and awe we have for statues and paintings, and from this derives the reward and honor of Artists; this was the glory of Timantes, Apeles, Phidias and Lysippus, and of so many others renowned for their fame, all who, rising above human forms, achieved with their ideas and works an admirable perfection. This Idea may then be called the perfection of Nature, the miracle of art, the clairvoyance of the intellect, the example of the mind, the light of imagination, the rising sun, which from the east inspires the statue of Menon, and inflames the monument of Prometheus.[72]

For the Romantics, especially in Germany, Greece continued to be seen as a model of life and culture. Nietzsche exclaimed, "Oh, the Greeks! They knew how to live!". Other scholars, likewise, despising the Roman filter, began to cultivate the ideals of Greek Classicism to such an extent that a veritable Grecomania was created, influencing all humanities and artistic forms.[73][74] In Neoclassicism, classical humanism was a significant impulse for the consolidation of democratic and republican concepts. According to Winckelmann, one of the mentors of the movement, only the Greeks had managed to produce Beauty, and for him and his colleagues, the Apollo Belvedere was the most perfect achievement of sculpture of all time. Winckelmann is also credited with the distinction between High and Low Classicism, labeling the former as "grand and austere," and the latter as "beautiful and flowing." Meanwhile, Classicism crossed the Atlantic and inspired the formation of the North American state and its school of sculpture.[75][76][77][78]

In the early twentieth century, academic studies multiplied and were refined to unprecedented levels with the development of new methods of archaeological research and the improvement of the theoretical and instrumental apparatus.[79] At the same time, in a way officializing the intense love for the classics that since the 18th century had been cultivated by German intellectuals, Classicism was co-opted by the Nazis, who saw in its formal models the glorified image of the Aryan race. They saw in its values the basis for the formation of a pure society, a healthy race and a strong state, establishing it as a reference standard for state-sponsored art and using it to justify the eradication of races and cultures deemed "degenerate", such as the Jews and modernist art.[80][81] Mussolini tried to propose a similar model for Fascist Italy, but it did not have much practical impact.[74]

The classical educational model began to lose vigor under the impact of the Modernist revolution, and the ability of classical sculpture to inspire new artists rushed into a fulminant decline, although it never disappeared at all. This recovery was greatly encouraged by the post-modernists, for whom there was no point in destroying tradition, as Modernism had proposed since this was tantamount to a loss of memory and past, tantamount to the creation of a useless void. Thus, it would be better to appropriate and update it through conscious criticism, appearing in the form of quotations, allegories, re-readings, and paraphrases, which offer a retrospective view and commentary on the old tradition.[74]

Today the formal patterns of classical Greek sculpture, its humanism and emphasis on the nude have found a new way to impress society, influencing the conception of beauty and practices regarding the body, resurrecting a cultivation of the physical that was born with the Greeks and influences various customs related to sexuality and the concept of body in media culture.

At the same time, a tendency is beginning to strengthen among art critics in the direction of abating the practically unanimous prestige that Modernism achieved and maintained for almost a century, with its individualistic, hermetic, irrational, abstracting, anti-historical and informal values beginning to be questioned. In this sense, the classical model may have a new attraction for artists and society in a context of updating the paideia, rescuing a line of work inspired by classical humanism, focused on the common good and the ethical and integral education of the public to which their works are directed, in a historical moment in which the emphasis on technology, along with consumerism, the excessive specialization of trades, wild urban life, ecological problems, the superficiality of mass culture, and the loss of strong moral references, have become threatening aspects for the well-being and the very survival of the human race.

Cultural tourism to museums and archaeological sites has been seen as a positive force for the dissemination of classical culture and art to the general public, although it may suffer from political manipulation and mercantilist degradation, possibly giving strength to simplistic, pasteurized, and uncritical views of the past.[82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89][90]

In any case, the presence of classical sculpture is still striking in Western culture, and with the wide Western penetration throughout the world, it has become known and appreciated globally. At least as far as the West is concerned, the appeal that the classical model has held throughout its history and still holds today attests to its persistent ability to stimulate the popular imagination and to be incorporated into a variety of cultural, ethical, social, and political ideologies.[63][91]

The classical heritage in the history of sculpture

-

Unknown author: Pasquino Group, 3rd century BC, Hellenistic, Roman copy.

-

Bust of Ptolemy I Soter, 3rd century BC, Hellenistic Egypt, original

-

Unknown author: Genius of Emperor Domitian, 1st - 2nd century A.D., Roman, original

-

Unknown author: The genius Hada, 2nd century AD, Gandhara culture, original.

-

Unknown author: The Good Shepherd, 4th century, paleochristian, original

-

Michelangelo: David, 1504, Renaissance

-

Unknown author: The German Man, 1934, Nazi art

See also

References

- ^ a b "Western Sculpture: Ancient Greek – The Classical period – Early Classical (c. 500–450 bc)". Encyclopaedia Britannica On line

- ^ BOARDMAN, John. "Greek Art and Architecture". In BOARDMAN, John; GRIFFIN, Jasper & MURRAY, Oswin. The Oxford History of Greece and the Hellenistic World. Oxford University Press, 1991. pp. 330–331

- ^ HERSEY, George. "Beauty is in the eye of a Greek chisel holder". The Offer, 31 May 1996.

- ^ THOMAS, Carol G. "Introduction". In THOMAS, Carol G. (ed). Paths from Ancient Greece. BRILL, 1988. pp. 1–5

- ^ GARDNER, Percy. "The Lamps of Greek Art". In LIVINGSTONE, R. W. The Legacy of Greece. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 353

- ^ WHITLEY, James. The Archaeology of Ancient Greece. Cambridge University Press, 2001. pp. 3–4

- ^ POLLITT, Jerome. Art and experience in classical Greece. Cambridge University Press, 1972. pp. 64–66

- ^ a b HEMINGWAY, Colette & HEMINGWAY, Seán. "The Art of Classical Greece (ca. 480–323 B.C.)". In: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, 2000.

- ^ POLLITT, p. 66

- ^ POLLITT, p. 70

- ^ MORRIS, Sarah. Daidalos and the Origins of Greek Art. Princeton University Press, 1992. pp. 363–364

- ^ POLLITT, p. 74

- ^ The period has a different chronology depending on the author consulted. The Encyclopedia Britannica extends it to c. 400 BC.

- ^ POLLITT, pp. 80–81

- ^ a b BOARDMAN, GRIFFIN & MURRAY. p. 332

- ^ LESSA, Fábio de Souza. "Corpo e Cidadania em Atenas Clássica". In THEML, Neyde; BUSTAMANTE, Regina Maria da Cunha & LESSA, Fábio de Souza (orgs). Olhares do corpo. Mauad Editora Ltda, 2003. pp. 48–49

- ^ STEINER, Deborah. Images in mind: Statues in Archaic and Classical Greek Literature and Thought. Princeton University Press, 2001. pp. 26–33; 35

- ^ BEARDSLEY, Monroe. Aesthetics from classical Greece to the present. University of Alabama Press, 1966. pp. 27–28

- ^ a b STEINER, pp. 39–40

- ^ STEWART, Andrew. "Notes on the Reception of the Polykleitan Style: Diomedes to Alexander". In MOON, Warren G. (ed). Polykleitos, the Doryphoros, and Tradition. University of Wisconsin Press, 1995. pp. 248–249

- ^ STEWART, pp. 247–253

- ^ TANNER, Jeremy. "Social Structure, Cultural Racionalisation and Aesthetic Judgement in Classical Greece". In RUTTER, N. Keith & SPARKES, Brian. Word and image in ancient Greece. Edinburgh University Press, 2000. pp. 185-ss

- ^ HURWIT, Jeffrey. "The Doryphoros: Looking Backward". In MOON, Warren G. (ed). Polykleitos, the Doryphoros, and Tradition. University of Wisconsin Press, 1995, pp. 3–7

- ^ STEINER, p. 40

- ^ HURWITT, Jeffrey. "The Parthenon and the Temple of Zeus at Olympia". In BARRINGER, Judith & POLLITT, Jerome (eds). Periklean Athens and its Legacy. University of Texas Press, 2005. pp. 135–142

- ^ MURRAY, John. A History of Greek Sculpture. Vol. II. Under Pheidias and his Successors. Adamant Media Corporation, 1883–2005. pp. 9–13; 17–20

- ^ LAPATIN, Kenneth. "The Statue of Athena and other Treasures in the Parthenon". In NEILS, Jennifer. The Parthenon. Cambridge University Press, 2005. pp. 261-ss

- ^ STEWART, p. 254

- ^ STEINER, pp. 34–35; 42

- ^ HALLIWELL, Stephen. "Plato and Painting". In RUTTER, N. Keith & SPARKES, Brian. Word and image in ancient Greece. Edinburgh University Press, 2000. pp. 101–102

- ^ TANNER, p. 183

- ^ a b "Western Sculpture: Ancient Greek: The Classical period: Late Classical period (c. 400–323 bc)". Encyclopaedia Britannica online

- ^ MOSSÉ, Claude. Athens in Decline, 404-86 B.C. Routledge, 1973. pp. 21–22; 25

- ^ STEINER, pp. 57–58; 62–65

- ^ HALLIWELL, Stephen. The Aesthetics of Mimesis: Ancient Texts and Modern Problems. Princeton University Press, 2000. pp. 37-ss; 72-ss; 98-ss

- ^ HALLIWELL, pp. 107–108

- ^ TANNER, p. 197

- ^ BOARDMAN, p. 331

- ^ SIFAKIS, Gregory Michael. Aristotle on the Function of Tragic Poetry. Crete University Press, 2001. pp. 40–42; 46–48

- ^ STEINER, p. 35

- ^ ENGGASS, Robert & BROWN, Jonathan. Italian and Spanish Art, 1600–1750: Sources and Documents. Northwestern University Press, 1992. p. 10

- ^ SIFAKIS, pp. 73-ss

- ^ STEINER, pp. 85–93

- ^ SPIVEY, Nigel. "Bionic Statues". In POWELL, Anton (ed). The Greek World. Routledge, 1995. pp. 448–450

- ^ SPIVEY, pp. 454–445

- ^ JANSON, Horst Woldemar. History of Art. Prentice Hall PTR, 2003. pp

- ^ a b "Late Classical Era Sculpture (c.400–323 BCE)". Encyclopedia of Irish and World Art.

- ^ KAMPEN, Natalie Boymel. "Epilogue: Gender and Desire". In KOLOSKI-OSTROW, Ann Olga & LYONS, Claire L. (eds). Naked Truths. Routledge, 1997. pp. 267–269

- ^ a b "Ancient Greek Sculpture". Encyclopedia of Irish and World Art.

- ^ OLIVER, Graham John. "Athenian Funerary Monumentos: Style, Grandeur and Cost". In OLIVER, Graham John (ed). The Epigraphy of Death: Studies in the History and Society of Greece and Rome. Liverpool University Press, 2000. pp. 59–79

- ^ STEARS, Karen. "The Times They Are A'Changing: Developments in Fifth-Century Funerary Sculpture". In OLIVER, Graham John (ed). The Epigraphy of Death: Studies in the History and Society of Greece and Rome. Liverpool University Press, 2000. pp. 25–58

- ^ ROBERTSON, Donald Struan. Greek and Roman architecture. Cambridge University Press, 1969. p. 195

- ^ MURATOV, Maya B. "Greek Terracotta Figurines with Articulated Limbs". In: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, 2000.

- ^ MERKER, Gloria. Corinth: The Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore: Terracotta Figurines of the Classical, Hellenistic, and Roman Periods. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 2000. p. 23

- ^ BARTMAN, Elizabeth. Ancient Sculptural Copies in Miniature. BRILL, 1992. p. 20

- ^ HIGGINS, Reynold Alleyne. Greek and Roman jewellery. Taylor & Francis, 1961. pp. 122–134

- ^ Department of Greek and Roman Art. "Roman Copies of Greek Statues". In: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, 2000.

- ^ McQUAID, Cate. "Sculpture show of a different color". The Boston Globe, 6 January 2008.

- ^ BENSON, J. L. Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements. University of Massachusetts Amherst, 2000

- ^ BARTMAN, pp. 16-ss

- ^ WHITLEY, p. 269

- ^ BOLGAR, R. R. The classical heritage and its beneficiaries. Cambridge University Press, 1973. pp. 1-ss

- ^ a b c HERSEY

- ^ a b "Greek Sculpture". Encyclopedia of Irish and World Art

- ^ TANNER, p. 10

- ^ OSBORNE, Robin. Archaic and Classical Greek Art. Oxford University Press, p. 240

- ^ THOMAS, pp. 1–5; 187-ss

- ^ LIVINGSTONE, R. W. The Legacy of Greece. Kessinger Publishing, 2005.

- ^ GREEN, Peter. Classical Bearings: Interpreting Ancient History and Culture. University of California Press, 1998. pp. 17–18

- ^ TSETSKHLADZE, Gocha R. "Introduction". In TSETSKHLADZE, Gocha R. (ed). Ancient Greeks West and East. BRILL, 1999. pp. vii-ss

- ^ JENKYNS, Richard. "The Legacy of Rome". In JENKYNS, Richard (ed.). The Legacy of Rome. Oxford University Press, 1992. pp. 1–5

- ^ ENGASS & BROWN, p. 15

- ^ BEHLER, Ernst. "The Force of Classical Greece in the Formation of Romantic Age in Germany". In THOMAS, Carol G. (ed). Paths from Ancient Greece. Brill, 1988, p. 118- ss

- ^ a b c Squire, Michael. "The Legacy of Greek Sculpture". In: Palagia, Olga (ed.). Handbook of Greek Sculpture. Walter de Gruyter, 2019, pp. 657–689

- ^ FEJFER, Jane. "Wiedewelt, Winkelmann and Antiquity". In FEJFER, Jane; FISCHER-HANSEN, Tobias & RATHJE, Annette. The rediscovery of antiquity. 10 Acta Hyperborea, 2003. University of Copenhagen; Museum Tusculanum Press. p. 230

- ^ GONTAR, Cybele. "Neoclassicism". In: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, 2000.

- ^ TOLLES, Thayer. "American Neoclassical Sculptors Abroad". In: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, 2000.

- ^ WHITLEY, p. 270

- ^ WEISBERG, Ruth. "Twentieth-Century Rhetoric: Enforcing Originality and Distancing the Past". In GAZDA, Elaine K. (ed). The ancient art of emulation. University of Michigan Press, 2002. p. 26

- ^ Sauquet, Mathilde. "Propaganda Art in Nazi Germany: The Revival of Classicism". In: The First-Year Papers (2010 – present). Trinity College Digital Repository, Hartford, 2014

- ^ Redner, ↵Harry. "Dialectics of Classicism: The birth of Nazism from the spirit of Classicism". In: Thesis Eleven, 2019; 152 (1):19–37

- ^ DUAYER, Juarez. Lukács e a atualidade da defesa do realismo na estética marxista. UNICAMP, sd.

- ^ PIZA, Daniel. "Nós que éramos tão modernos". O Estado de S. Paulo, 16 December 2007.

- ^ CLAIBORNE, Lise. "Beyond Readiness: New Questions about Cultural Understanding and Developmental Appropriateness". In KINCHELOE, Joe. The Praeger Handbook of Education and Psychology. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007. P. 434

- ^ BOLGAR, pp. 380–393

- ^ GREEN, p. 16

- ^ TYMIENIECZKA, Anna-Teresa. "The Theme: Philosophy/Phenomenology of Life inspiring Education for Our Times". In TYMIENIECZKA, Anna-Teresa (ed). Paideia. Springer, 2000. pp. 2–3

- ^ Walsh, Kevin (1992). The Representation of the Past: Museums and Heritage in the Postmodern World. Routledge. ISBN 9780415079440.

- ^ SHANKS, Michael. Classical Archaeology of Greece. Routledge, 1996. pp. 176-ss

- ^ LIVINGSTONE, Richard Winn. Greek ideals and modern life. Biblo & Tannen Publishers, 1969. p. 1

- ^ AGARD, Walter Raymond. The Greek Tradition in Sculpture. Ayer Publishing, 1950. p. 8

Notes

- ^ However, as happens in all processes of artistic evolution, any dates that are rigorously defined usually prove to be inaccurate and subject to dispute, there always being elements of transition before and after the period in question, making the spectrum diffuse and difficult to characterize, thus adopting delimitations established by tradition.