Mycena aurantiomarginata

| Mycena aurantiomarginata | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Agaricales |

| Family: | Mycenaceae |

| Genus: | Mycena |

| Species: | M. aurantiomarginata

|

| Binomial name | |

| Mycena aurantiomarginata | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| Mycena aurantiomarginata | |

|---|---|

| Gills on hymenium | |

| Cap is conical or campanulate | |

| Hymenium is adnate | |

| Stipe is bare | |

| Spore print is white | |

| Ecology is saprotrophic | |

| Edibility is unknown | |

Mycena aurantiomarginata, commonly known as the golden-edge bonnet, is a species of agaric fungus in the family Mycenaceae. First formally described in 1803, it was given its current name in 1872. Widely distributed, it is common in Europe and North America, and has also been collected in North Africa, Central America, and Japan. The fungus is saprobic, and produces fruit bodies (mushrooms) that grow on the floor of coniferous forests. The mushrooms have a bell-shaped to conical cap up to 2 cm (3⁄4 in) in diameter, set atop a slender stipe up to 6 cm (2+3⁄8 in) long with yellow to orange hairs at the base. The fungus is named after its characteristic bright orange gill edges. A microscopic characteristic is the club-shaped cystidia that are covered with numerous spiky projections, resembling a mace. The edibility of the mushroom has not been determined. M. aurantiomarginata can be distinguished from similar Mycena species by differences in size, color, and substrate. A 2010 publication reported the discovery and characterization of a novel pigment named mycenaaurin A, isolated from the mushroom. The pigment is responsible for its color, and it has antibiotic activity that may function to prevent certain bacteria from growing on the mushroom.

Taxonomy

The species, originally named Agaricus marginatus by the Danish naturalist Heinrich Christian Friedrich Schumacher in 1803, has several synonyms.[2] Elias Magnus Fries renamed it Agaricus aurantio-marginatus in his 1821 Systema Mycologicum,[3] while Christiaan Hendrik Persoon called it Agaricus schumacheri in 1828.[4] Although Schumacher had the earliest publication date, Fries's name is sanctioned, and so the specific epithet he used is given nomenclatural precedence. French mycologist Lucien Quélet transferred the species to the genus Mycena in 1872.[5] In 1930 Karel Cejp considered it to be a variety of Mycena elegans.[6]

According to Alexander H. Smith's organization of the genus Mycena, M. aurantiomarginata is classified in section Calodontes, subsection Granulatae, which contains species with roughened cheilocystidia (cystidia on gill edges), such as M. rosella, M. flavescens, M. elegans, and M. strobilinoides.[7] In his 1992 study of Mycena, Dutch mycologist Rudolph Arnold Maas Geesteranus put M. aurantiomarginata in the section Luculentae, characterized by species with an olive to yellowish-olive and moist cap, pallid to gray-olive gills with bright orange margins, brownish to grayish-olive stipes, white spore deposit, and spiny cystidia.[8] M. aurantiomarginata was included in a 2010 molecular analysis focused on clarifying the phylogenetic relationships between Northern European species in the section Calodontes. The results suggested that, based on the similarity of nuclear large subunit ribosomal DNA sequences, the fungus is closely related to M. crocata and M. leaiana.[9] This conclusion was previously corroborated by research that used molecular analysis to demonstrate that several Mycena species can be mycorrhizal partners of the orchid Gastrodia confusa.[10]

The specific epithet aurantiomarginata is Latin, and refers to the orange edges of its gills (aurantius, "orange"; marginata, "bordered").[11] In the United Kingdom, the mushroom is commonly known as the "golden-edge bonnet".[12]

Description

The cap of M. aurantiomarginata ranges in shape from obtusely conic to bell-shaped, and becomes flat in maturity, reaching diameters of 0.8–2.0 cm (3⁄8–3⁄4 in). The cap color is variable, ranging from dark olive fuscous (dark brownish-gray) to yellowish-olive in the center, while the margin is orangish. Alexander H. Smith, in his 1947 monograph of North American Mycena species, stated that the caps are not hygrophanous (changing color depending on the level of hydration),[13] while Mycena specialist Arne Aronsen says they are.[14] The overall color fades as the mushroom ages.[15] The surface is moist, and young individuals are covered with fine whitish powder, but this soon sloughs off to leave a polished surface that develops radial grooves in maturity.[13] The flesh is thin (about 1 mm thick in the center of the cap) and flexible.[15]

Gills are adnate with a decurrent tooth (where the gills curve up to join the stipe but then, close to the stipe, the margin turns down again), and initially narrow but broaden when old. They are pallid to grayish-olive with bright orange edges.[13] Smith noted that the edge color may spread to the gill faces in some specimens, because the pigment, rather than being encrusted on the walls of the cystidia, is found in the cytosol and therefore more readily diffusible.[16] The gills are spaced close together, with between 16 and 26 gills reaching the stipe,[14] and there are up to three tiers of interspersed lamellulae (short gills that do not extend fully from the cap edge to the stipe).[15]

The cylindrical stipe is 3–6 cm (1+1⁄8–2+3⁄8 in) long by 0.1–0.2 cm (1⁄32–3⁄32 in) thick, hollow, and stiff but flexible;[13] it is somewhat thicker at the base.[17] It has a brownish to grayish-olive color that is sometimes tinged with shades of orange. The surface is smooth except for orange powder near the top, while the base is covered with stiff orange hairs. Smith reports the mushroom tissue to have no distinctive taste or odor,[13] while Aronsen says the odor is "very conspicuous; sweet, fruity, often experienced as farinaceous or faintly of anise".[14] Like many small Mycena species, the edibility of the mushroom is unknown, as it is too insubstantial to consider collecting for the table.[16]

The spores are elliptic, smooth, and amyloid, with dimensions of 7–9 by 4–5 μm.[13] The basidia (spore-bearing cells of the hymenium) are club-shaped, four-spored, and measure 25–32 by 5.5–7 μm.[14] Pleurocystidia and cheilocystidia (cystidia on the gill faces and edges, respectively) are abundant and similar in morphology: club-shaped to somewhat capitate (with a head),[13] the tops sparsely to densely covered with small spines (said to resemble a mace),[18] filled with a bright orange pigment, and measuring 28–36 by 7–12 μm. The flesh of the cap is covered with a cuticle, on the surface of which are found scattered cystidia similar to those on the gills. Directly beneath the cuticle is a layer of enlarged cells, and beneath this are filamentous hyphae.[13] Clamp connections are present in the hyphae.[14]

Mycena aurantiomarginata uses a tetrapolar mating system, whereby genes at two different locations on the chromosomes regulate sexual compatibility, or mating type. This system prevents self-fertilization and ensures a high degree of genotypic diversity. When the fungal mycelia is grown in culture on a petri dish, the colonies are white, odorless, and typically have a central patch of congested aerial hyphae that grow upward from the colony surface, which abruptly become flattened to submerged, and occasionally form faint zone lines. The hyphae commonly form deposits of tiny amorphous crystals where they contact other mycelial fronts, especially where the hyphae are vegetatively incompatible and destroy each other by lysis.[19]

Similar species

Mycena aurantiomarginata is generally recognizable in the field by its olive-brown to orangish cap, bright orange gill edges, and yellowish hairs at the base of the stipe. M. elegans is similar in appearance to M. aurantiomarginata, and some have considered them synonymous.[20] M. elegans is larger, with a cap diameter up to 3.5 cm (1+3⁄8 in) and stipe length up to 12 cm (4+3⁄4 in), darker, and has pale greenish-yellow colors on the gill edges and stipes that stain dull reddish-brown in age.[21] M. leaiana is readily distinguished from M. aurantiomarginata by the bright orange color of its fruit bodies, its clustered growth on rotting wood, and the presence of a gelatinous layer on its stipe.[22] M. strobilinoides closely resembles M. aurantiomarginata in shape, size, spore morphology, and the presence of hairs at the stipe base. It has a cap color that ranges from scarlet to yellow, and features scarlet edges on widely spaced, pale pinkish-orange to yellow gills.[23]

Habitat and distribution

Mycena aurantiomarginata is a saprobic fungus, deriving nutrients from decomposing organic matter found on the forest floor, such as needle carpets. Fruit bodies of the fungus grow scattered, in groups, or in tufts under conifers (usually spruce and fir), and are often found on moss. In North America, it is found in California, Washington, Oregon, and British Columbia,[24] and the species is widely distributed in western and northern Europe.[25] In Central America, the mushroom has been collected on the summit of Cerro de la Muerte in the Cordillera de Talamanca, Costa Rica, on leaf litter of Comarostaphylis arbutoides (a highly branched evergreen shrub or tree in the heath family).[26] In 2010, it was reported from Hokkaido in northern Japan, where it was found growing on Picea glehnii forest litter in early winter.[27] It has also been recorded from North Africa.[28]

Bioactive compounds

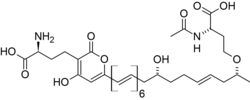

In 2010, a pigment compound isolated and characterized from fruit bodies of Mycena aurantiomarginata was reported as new to science by Robert Jaeger and Peter Spiteller in the Journal of Natural Products. The chemical, mycenaaurin A, is a polyene compound that consists of a tridecaketide (i.e., 13 adjacent methylene bridge and carbonyl functional groups with two amino acid moieties on either end of the molecule). The authors posit that the flanking amino acid groups are probably derived biosynthetically from S-Adenosyl methionine. The tridecaketide itself contains an alpha-pyrone, a conjugated hexaene, and a single alkenyl moiety. Jaeger and Spiteller suggest that mycenaaurin A might function as a defense compound, since it exhibits antibacterial activity against the Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus pumilus. The chemical is only present in the fruit bodies, and not in the colorless mycelia.[29] An earlier screening for antimicrobial activity in the fruit bodies revealed a weak ability to inhibit the growth of the fungi Candida albicans and Aspergillus fumigatus.[30]

References

- ^ "Mycena aurantiomarginata (Fr.) Quél. 1872". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. Retrieved 2013-01-01.

- ^ Schumacher HCF. (1803). Enumeratio Plantarum, in Partibus Sællandiae Septentrionalis et Orientalis Crescentium (in Latin). Vol. 2. Copenhagen, Denmark: F. Brummer.

- ^ Fries EM. (1821). Systema Mycologicum (in Latin). Vol. 1. Greifswald, Germany: Sumtibus Ernesti Mauritii. p. 113. ISBN 9780520271081.

- ^ Persoon CH. (1828). Mycologia Europaea. Vol. 3. Erlangen, Germany: Bavarian State Library. p. 230.

- ^ Quélet L. (1872). "Les Champignons du Jura et des Vosges". Mémoires de la Société d'Émulation de Montbéliard. II (in French). 5: 240.

- ^ "Mycena elegans var. aurantiomarginata (Fr.) Cejp 1930". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. Retrieved 2013-01-01.

- ^ Smith (1947), p. 196.

- ^ Mass Geesteranus RA. (1992). Mycenas of the Northern Hemisphere. II. Conspectus of the Mycenas of the Northern Hemisphere. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Vetenschappen. ISBN 978-0-444-85757-6.

- ^ Harder CB, Læssøe T, Kjøller R, Frøslev TG (2010). "A comparison between ITS phylogenetic relationships and morphological species recognition within Mycena sect. Calodontes in Northern Europe". Mycological Progress. 9 (3): 395–405. doi:10.1007/s11557-009-0648-7. S2CID 20653008.

- ^ Ogura-Tsujita Y, Gebauer G, Hashimoto T, Umata H, Yukawa T (2009). "Evidence for novel and specialized mycorrhizal parasitism: The orchid Gastrodia confusa gains carbon from saprotrophic Mycena". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 276 (1657): 761–7. doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.1225. PMC 2660934. PMID 19004757.

- ^ Rea C. (1922). British Basidiomycetae: A Handbook to the Larger British Fungi. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 374.

- ^ "Recommended English Names for Fungi in the UK-Revised". Scottish Fungi. Retrieved 2013-01-01.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Smith (1947), pp. 198–9.

- ^ a b c d e Aronsen A. (22 September 2004). "Mycena aurantiomarginata". A key to the Mycenas of Norway. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014. Retrieved 2013-01-01.

- ^ a b c Wood M, Stevens F. "Mycena aurantiomarginata". California Fungi. Retrieved 2013-01-01.

- ^ a b Smith AH. (1975). A Field Guide to Western Mushrooms. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. p. 157. ISBN 0-472-85599-9.

- ^ Massee G. (1922). British Fungus-flora. A Classified Text-book of Mycology. Vol. 3. London, UK: G. Bell & Sons. p. 117.

- ^ Trudell S, Ammirati J (2009). Mushrooms of the Pacific Northwest. Timber Press Field Guide. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-88192-935-5.

- ^ Petersen RH. (1997). "Mating systems in Hymenomycetes: New reports and taxonomic implications". Mycotaxon. 63: 225–59.

- ^ Konrad P. (1931). "Notes critiques sur quelques champignons du Jura (cinquième série)". Bulletin Trimestriel de la Société Mycologique de France (in French). 47: 129–48.

- ^ Smith (1947), p. 202.

- ^ Smith (1947), p. 413.

- ^ Arora D. (1986). Mushrooms Demystified: A Comprehensive Guide to the Fleshy Fungi. Berkeley, California: Ten Speed Press. p. 228. ISBN 0-89815-169-4.

- ^ Gibson I. (2012). Klinkenberg B. (ed.). "Mycena aurantiomarginata (Fr.) Quel". E-Flora BC: Electronic Atlas of the Plants of British Columbia. Lab for Advanced Spatial Analysis, Department of Geography, University of British Columbia, Vancouver. Archived from the original on 2014-05-17. Retrieved 2013-01-01.

- ^ "Species: Mycena aurantiomarginata (Fr.) Quél. 1872". Global Biodiversity Information Facility. Retrieved 2010-12-12.

- ^ Halling RE, Mueller GM. "Mycena aurantiomarginata". Macrofungi of Costa Rica. Retrieved 2013-01-01.

- ^ Shirayama H. (2010). "Mycena aurantiomarginata newly recorded from Japan". Transactions of the Mycological Society of Japan (in Japanese). 51 (1): 22–5. ISSN 0029-0289.

- ^ Breitenbach J, Kränzlin F (1991). Fungi of Switzerland: A Contribution to the Knowledge of the Fungal Flora of Switzerland : Boletes and Aparics. Vol. 3. Lucerne, Switzerland: Verlag Edition Mycologia/Mad River Press. ISBN 978-3-85604-030-7.

- ^ Jaeger RJ, Spiteller P (2010). "Mycenaaurin A, an antibacterial polyene pigment from the fruiting bodies of Mycena aurantiomarginata". Journal of Natural Products. 73 (8): 1350–4. doi:10.1021/np100155z. PMID 20617819.

- ^ Suay I, Arenal F, Asensio FJ, Basilio A, Cabello MA, Díez MT, García JB, González del Val A, Gorrochategui J, Hernández P, Peláez F, Vicente MF (2000). "Screening of basidiomycetes for antimicrobial activities". Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 78 (2): 129–39. doi:10.1023/A:1026552024021. PMID 11204765. S2CID 23654559.

Cited text

- Smith AH. (1947). North American Species of Mycena. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

External links

Media related to Mycena aurantiomarginata at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mycena aurantiomarginata at Wikimedia Commons- Mycena aurantiomarginata in Index Fungorum