Pennantia baylisiana

| Pennantia baylisiana | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Apiales |

| Family: | Pennantiaceae |

| Genus: | Pennantia |

| Species: | P. baylisiana

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pennantia baylisiana (W.R.B.Oliv.) G.T.S.Baylis[3]

| |

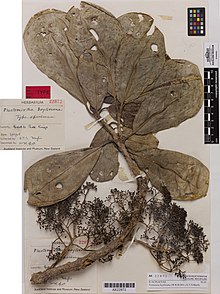

Pennantia baylisiana, commonly known as Three Kings kaikōmako or kaikōmako manawatāwhi (Māori), is a species of plant in the family Pennantiaceae (Icacinaceae in older classifications). It is endemic to Manawatāwhi / Three Kings Islands, around 55 kilometres (34 mi) northwest of Cape Reinga, New Zealand. At the time of its discovery just one plant remained. This single tree grows on a scree slope inaccessible to browsing goats, and has been called "the world's loneliest tree".[4] The species was discovered in 1945 by botanist Geoff Baylis and described in 1948, although it took decades before it was it was fully accepted as a distinct species of Pennantia. Although the only wild tree is female, it was successfully propagated from cuttings in the 1950s, one of which was induced to self-pollinate in 1985. Subsequent seed-grown plants have themselves set seeds, and the species has been replanted on the island, the adjoining mainland, and in public and private gardens around New Zealand.

Description

Pennantia baylisiana is a shrubby, multi-trunked tree with a broad crown, unlike the three other species in the genus Pennantia. It does not have a divaricating juvenile form, unlike the other New Zealand Pennantia species kaikōmako (P. corymbosa).[5] It grows to a height of 5 m in the wild, though has been recorded reaching 8 m in cultivation. It has pale greyish-brown bark and branchlets that are covered with lenticels.[5][6]

It has leathery, green, egg-shaped alternate leaves around 12–16 by 7–10 cm. Adult leaves have smooth margins but young leaves are toothed. The leaves are large and flat in shade-grown plants, up to 20 by 10 cm, but notably curled along their sides – almost rolled – on branchlets exposed to sun and wind. They have distinctive hair-covered domatia on the underside, at the junction of the midrib and secondary veins, and are suspended from 2.5 cm long petioles.[5][6]

Flowering occurs from October to November, producing 1.5 by 1.5 mm greenish-white flowers in panicles with 2.6 mm petals. Flowers usually arise on woody branches, though some are terminal. The stamen is made up of a 1–1.4 mm long anther on top of a 1.5 mm long filament, though the pollen is usually sterile. It has a 2.8 by 2 mm cylindrical ovary with a stigmatic ring 1.5–1.8 mm in diameter. Fruiting is from January through to April in cultivated plants yielding 10 by 4.5 mm ellipsoid fruit. Mature fruit are purple to black and have a single hard 9 by 3.5 mm seed.[5][6] Its chromosome number is 2n = 50, as with P. corymbosa.[7]

-

Foliage, showing distinctive rolled leaves

-

Flowers in bud

-

Foliage, from beneath

Discovery

Pennantia baylisiana was discovered by New Zealand botanist Geoff Baylis in 1945 when he visited Great Island, the largest of the Manawatāwhi / Three Kings Islands, on a botanical expedition. The Three Kings are located around 55 kilometres (34 mi) northwest of Cape Reinga, and at the time were relatively unknown botanically, with the only collecting expeditions in 1887 and 1889 (both by Thomas Cheeseman, director of Auckland Museum, who had only a few hours ashore), 1928, and 1934.[8] Baylis spent a week on the island in November–December 1945, and collected samples of 83 species of plants for Auckland Museum.

By this time wild goats had eaten the place out. Part was closely browsed grass but most was kanuka forest or scrub. Cheeseman's novelties survived in small numbers beyond browse range. It was easy to see that the grassland offered nothing new, but the kanuka canopy was broken here and there by other textures and shades of green. I located these places by climbing trees at every vantage point and reached them deviously via bluffs and screes since except in the main valley they were, even for goats, a bit inaccessible.[9]

Four of Baylis's discoveries were new to science, including Suttonia dentata (now Myrsine oliveri), Tecomanthe speciosa (which like P. baylisiana was represented by a single living individual), and Brachyglottis arborescens.[10] After collecting the latter two, he describes coming across P. baylisiana:

The last little grove that I investigated lay near the highest point of the island down a scree of boulders about 200m above the sea. I was drawn to it by what looked like a karaka. I was soon gazing upon it in disbelief since a third find seemed too much to expect. But this was no karaka – its leaves were larger and recurved strongly in the sun, its bunches of small green flowers sprang from the bare branches below the leaves and there were no big berries – indeed none at all.[9]

He noted that the 15-foot tree was living on a seaward scree slope of greywacke boulders at an altitude of 700 feet, with pōhutukawa (Meterosideros excelsa), kānuka (Kunzea ericoides), coastal maire (Nestegis apetala), and whārangi (Melicope ternata) growing nearby. The tree was forked at the base and badly eaten by insects.[10] Baylis collected the holotype specimen of P. baylisiana (housed in Auckland War Memorial Museum)[11] on 2 December 1945.

Taxonomy

The species was described by Director of Auckland Museum Walter Oliver in 1948. Oliver noted its resemblance to the genus Corynocarpus, which includes the New Zealand species karaka (Corynocarpus laevigatus). Corynocarpus had until recently been considered to be in the family Anacardiaceae, which is where Oliver placed this species, erecting a new genus Plectomirtha to contain it and giving it the specific epithet baylisiana in recognition of the plant’s discoverer Geoff Baylis.[10]

Oliver had not noticed the plant's similarity to the mainland New Zealand species kaikōmako (Pennantia corymbosa); indeed, Sleumer in 1970 working from herbarium sheets proposed that the species not only belonged in the genus Pennantia, but was a synonym of P. endlicheri from Norfolk Island which has similarly-large leaves.[12] Baylis disagreed and maintained that P. baylisiana was a distinct species of Pennantia, citing amongst other features its distinctive thickened and curled leaves, its thicker twigs, and panicles of flowers that mostly arose directly from the trunk rather than at the ends of branches (known as cauliflory).[13] In 1977 he wrote:

It is not often that a botanist can decently attach his own name to a plant, but this paper aims to establish that the Three Kings tree is like most of the Three Kings endemics, the remains of a distinctive population.[14]

The importance of this distinction rested on the fact that only a single female tree remained on the Three Kings. If it and the Norfolk Island Pennantia were the same species it could be hybridised with Norfolk Island male trees and create a new and genetically variable population.[15]

In their 2002 revision of the genus Pennantia, Gardner and de Lange concluded that P. baylisiana was indeed distinct from P. endlicheri, having large, hairy domatia at the junction of leaf midrib and lateral veins (P. endlicheri's are small and hairless), a different arrangement of the stigmas, and thicker pedicels.[15][6] A DNA phylogeny confirmed its distinctiveness, placing P. corymbosa and P. endlicheri as each other's closest relatives and P. baylisiana as sister taxon to both of them, the three species diverging some time within the last 9 million years.[16]

Distribution

It is only found in the wild on Manawatāwhi / Three Kings Islands, an island chain 55 kilometres (34 mi) north-west of the top of the North Island, on Great Island (Manawatāwhi). There is only one tree known in the wild; a female growing above a cliff on the northern face of Great Island. [17][5][18][19] This tree has been called "the loneliest tree".[20]

The species has now been propagated by plantings in various garden locations in New Zealand, including Otari-Wilton's Bush,[21] and around 200 saplings have been planted in Northland.[17]

Conservation

Manawatāwhi / Great Island had been inhabited by Māori for at least 200 years, during which time they farmed goats and pigs and cleared the forest – along the coast predominantly puka, Meryta sinclairii – from almost all cultivatable land. Māori occupation ended around 1840, and all livestock seem to have been removed at that time. When Cheeseman landed in 1887, the island was almost covered with kānuka, and regenerating forest trees were plentiful (although Meryta sinclairii did not reappear until 1946, which led Baylis to speculate that some goats may still have been present and preventing this species from re-establishing).[22] The government survey party decided that Great Island needed to be stocked with animals that could feed shipwrecked sailors, so on Cheeseman's second collecting trip in 1889 four goats were released. They increased rapidly in numbers, stopping forest regeneration and almost driving some species to extinction. At the time Baylis visited in 1945, nearly 50 plant species had been driven locally extinct on Great Island, and others had been almost eliminated, with only a few or a single individual surviving in places inaccessible to goats.[22] In 1946 a Government shooting party was sent to the island and killed all 398 goats present.[10]

This species is threatened by habitat loss.[23] The one tree remaining in the wild at Three Kings Island is at significant risk from storm damage, droughts and senescence.[5][17] P. baylisiana was previously recognised by The Guinness Book of World Records as the rarest tree in the world.[24]

After discovering the tree in 1945, Baylis brought its only sucker shoot back to Auckland, and planted it in his Dunedin garden, where it eventually took root.[25] Following his death, his colleagues continued to care for the seedling, and after around 40 years they noted that it had set seed. Attempts to root cuttings from the crown of the tree by both the DSIR Plant Diseases Division and the commercial New Plymouth nursery Duncan and Davies had failed. As Baylis later related,

[In 1950] I asked George Smith the chief propagator at New Plymouth what I might do to provide better cuttings. "Cut the tree down" he said, and while I shuddered at the thought he explained that he was confident about rooting shoots from the stump. But would there be any? Well, the tree had four trunks so I dared to sever one. A year later the shoots were there, the Naval launch on which I was a guest gave them a quick passage to New Plymouth which happened to be its next port and Mr Smith soon placed the survival of "Plectomirtha" beyond doubt.[9]

Cuttings were raised for 20 years at the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research. Hardwood cuttings of P. baylisiana can take 10 months to root, and the young trees, which were clones of the single wild tree, often died in the first year.[9] From the 1970s onwards, cuttings from this generation of plants were propagated by specialist plant growers and made available to gardeners.[25] In cultivation the trees grow readily in sun or shade, and can tolerate wind and drought, and even light frost.[26][25]

P. baylisiana is dioecious, and the remaining wild tree was thought to be entirely female. In the late 1980s, fruit was found for the first time on the one tree remaining in the wild, indicating that on occasion viable pollen was produced and self-fertilisation could occur, a rare occurrence in dioecious plants.[27] However, it was discovered that few of self-pollinated fruit were fertile (around 1 in 2000).[24]

In 1985 Ross Beever from Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research used plant hormone to produce viable pollen on a female tree in cultivation at Mt Albert Research Centre, using hand-pollination to achieve self-fertilisation. One the seedlings produced as a result, named "Martha", was naturally self-fertile and from the early 1990s produced a good amount of seed without hand-pollination, allowing many saplings to be grown.[28][17][4] These plants were generally self-fertile, taking four or five years to produce fruit and seed.[25] By 1998 hundreds of saplings had been grown from seed, but these were not immediately replanted on Great Island, for fear of introducing bacteria or fungal disease which could attack the remaining wild tree.[25] In 2010 the Department of Conservation planted 1,600 P. baylisiana seeds from mainland fruit back on Great Island, after carefully treating them to avoid introducing pathogens.[29]

In 2019, two hundred saplings raised by Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research were given to Ngāti Kurī, a Māori iwi from Northland, whose traditional tribal area (Template:Lang-mi) includes the Three Kings Islands. These saplings have been planted around the Waiora marae at Ngātaki, north of Kaitaia.[17][30]

References

- ^ de Lange, P. (2014). "Pennantia baylisiana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T30481A62768931. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-2.RLTS.T30481A62768931.en. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ "Assessment Details for Pennantia baylisiana (W.R.B.Oliv.) G.T.S.Baylis". NZTCS. 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ "Pennantia baylisiana (W.R.B.Oliv.) G.T.S.Baylis - Biota of NZ". New Zealand Plant Names Database. Manaaki Whenua - Landcare Research. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ a b Renwick, Dustin (25 December 2019). "The story of the world's loneliest tree". National Geographic. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f de Lange, Peter J. (2003). "Pennantia baylisiana Fact Sheet". New Zealand Plant Conservation Network. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d Dawson, John; Lucas, Rob (2019). New Zealand's Native Trees. with Jane Connor & Barry Sneddon (Revised ed.). Nelson, New Zealand: Potton & Burton. ISBN 978-0-947503-98-7. OCLC 1126327869.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Murray, B. G.; De Lange, P. J. (1995). "Chromosome numbers in the rare endemic Pennantia baylisiana (W.R.B. Oliv.) G.T.S. Baylis (Icacinaceae) and related species". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 33 (4): 563–564. doi:10.1080/0028825X.1995.10410628.

- ^ "Pennantia baylisiana - The University of Auckland". www.nzplants.auckland.ac.nz. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d Baylis, G. T. S. (March 1997). "Pennantia baylisiana, New Zealand's rarest tree—its discovery and propagation". Journal of the Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture. 2 (1): 12–13.

- ^ a b c d Oliver, W.R.B. (1948). "The Flora of the Three Kings Islands". Records of the Auckland Institute and Museum. 3 (4/5): 211–238 – via BHL.

- ^ "Pennantia baylisiana Holotype". Auckland War Memorial Museum Collections Online.

- ^ Sleumer, H. (1970). "The identity of Plectomirtha Oliv. with Pennantia J. R. & G. Forster." Blumea 18: 217–218.

- ^ Baylis, G. R. F. (March 1989). "Pennantia baylisiana (W. Oliver) Baylis". New Zealand Botanical Society Newsletter. 15: 13.

- ^ Baylis, G. T. S. (1977). "Pennantia baylisiana (Oliver) Baylis comb. nov". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 15 (2): 511–512. doi:10.1080/0028825X.1977.10432558.

- ^ a b Gardner, Rhys O.; de Lange, Peter J. (2002). "Revision of Pennantia (Icacinaceae), a small isolated genus of Southern Hemisphere trees". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 32 (4): 669–695. doi:10.1080/03014223.2002.9517715. ISSN 0303-6758. S2CID 83782970.

- ^ Maurin, Kévin J. L. (2020). "A dated phylogeny of the genus Pennantia (Pennantiaceae) based on whole chloroplast genome and nuclear ribosomal 18S–26S repeat region sequences". PhytoKeys (155): 15–32. doi:10.3897/phytokeys.155.53460. PMC 7428460. PMID 32863722.

- ^ a b c d e "World's rarest tree comes home to the Far North". Northern Advocate. 25 August 2019. ISSN 1170-0777. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- ^ Eagle, Audrey Lily (2006). Eagle's complete trees and shrubs of New Zealand. Audrey Lily Eagle, Audrey Lily Eagle. Wellington, N.Z.: Te Papa Press. p. 420. ISBN 978-0-909010-08-9. OCLC 85262201.

- ^ "Table 3: Area (in 100 km2) of data contributions per country and within protected areas". doi:10.7717/peerj.4096/table-3.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "The loneliest tree: Kaikōmako manawatāwhi". Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington, NZ. 1 September 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ^ Dooney, Laura (24 July 2016). "CuriousCity: How Wellington's Otari-Wilton's Bush is saving our native plants". Stuff. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ a b Baylis, G.T.S. (1948). "Vegetation of Great Island, Three Kings Group". Records of the Auckland Institute and Museum. 3 (4/5): 239–252. JSTOR 42906014 – via JSTOR.

- ^ "Kaikōmako manawa tāwhi (Pennantia baylisiana) returned to iwi". Manaaki Whenua. August 2019. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ a b Judd, Warren (January–March 1996). "The Clifftop World of the Three Kings". NZ Geographic (29). Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Gardner, Rhys O.; de Lange, Peter J.; Davidson, Geoff (June 2004). "Fruit and seed of Pennantia baylisiana (Pennantiaceae)". New Zealand Botanical Society Newsletter. 76: 21–23.

- ^ Bannister, P. (1984). "Winter frost resistance of leaves of some plants from the Three Kings Islands, grown outdoors in Dunedin, New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 22 (2): 303–306. doi:10.1080/0028825X.1984.10425258.

- ^ Webb, C. J. (1996). "The breeding system of Pennantia baylisiana (Icacinaceae)". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 34 (3): 421–422. doi:10.1080/0028825X.1996.10410706. ISSN 0028-825X.

- ^ "New Zealand's rarest tree back form the brink". Science Learning. 31 May 2010. Archived from the original on 20 December 2012. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ Platt, John (20 April 2010). "World's rarest tree gets some help". Scientific American. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ^ "Kaikōmako manawa tāwhi (Pennantia baylisiana) returned to iwi". Manaaki Whenua. 1 August 2019. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

External links

- Kaikōmako manawa tāwhi (Pennantia baylisiana) returns to the Far North and Ngāti Kuri Video by Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research

- Pennantia baylisiana discussed on RNZ Critter of the Week, 10 January 2022

- "Native tree saved from extinction, returned to iwi"; RNZ interview with Sheridan Waitai of Ngāti Kurī, 13 August 2019