Ahmed Barzani revolt

| Ahmed Barzani revolt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Kurdish–Iraqi conflict[2] | |||||||

Mountain gun of the Iraqi Army column, 'Dicol', shelling Shirwan-A-Mazin from a hillside at Kani-Ling during the Ahmed Barzani revolt, June 1932 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Barzan tribe | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

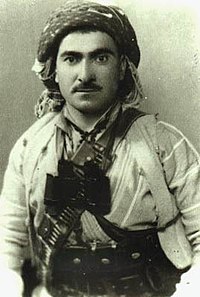

Ahmed Barzani Mustafa Barzani[3] | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| |||||||

Ahmed Barzani revolt refers to the first of the major Barzani revolts and the third Kurdish nationalistic insurrection in modern Iraq. The revolt began in 1931, after Ahmed Barzani, one of the most prominent Kurdish leaders in southern Kurdistan, succeeded in unifying a number of other Kurdish tribes.[4] The ambitious Kurdish leader enlisted a number of Kurdish leaders into the revolt, including his young brother Mustafa Barzani, who became one of the most notorious commanders during this revolt. The Barzani forces were eventually overpowered by the Iraqi Army with British support, forcing the leaders of Barzan to go underground.

Ahmed Barzani was later forced to flee to Turkey, where he was held in detention and then sent to exile in the south of Iraq. Although initially a tribal dispute, the involvement of the Iraqi government inadvertently led to the growth of Shaykh Ahmed and Mulla Mustafa Barzani as prominent Kurdish leaders. Throughout these early conflicts the Barzanis consistently displayed their leadership and military prowess, providing steady opposition to the fledgling Iraqi military. It is speculated that exile in the major cities exposed the Barzanis to the ideas of urban Kurdish nationalism.

Background

Early Kurdish separatism

Shortly after the final accords of World War I, Sheykh Mahmud Barzanji of the Qadiriyyah order of Sufis, the most influential personality in southern Kurdistan,[5] was appointed Governor of the former sanjak of Duhok. Sheikh Mahmud led the first Kurdish revolt in British-controlled southern Kurdistan (Iraqi Kurdistan) in May 1919. Using his authority as a religious leader, Sheykh Mahmud called for a jihad against the British in 1919 and thus acquired the support of many Kurds indifferent to the nationalist struggle. Although the intensity of their struggle was motivated by religion, Kurdish peasantry seized the idea of “national and political liberty for all” and strove for “an improvement in their social standing”.

Among Mahmud's many supporters and leaders was 16-year-old Mustafa Barzani, the future leader of the Kurdish nationalist cause and commander of Peshmerga forces in Kurdish Iraq. The Barzani fighters were only a part of the Sheykh's 500-person force. As the British became aware of the sheikh's growing political and military power, they were forced to respond militarily. Two British brigades were deployed to defeat Sheikh Mahmoud's fighters at Darbandi Bazyan near Sulaimaniyah in June 1919. Sheikh Mahmoud was eventually arrested and exiled to India in 1921. Mahmud's fighters continued to oppose British rule after his arrest. Although no longer organized under one leader, this intertribal force was “actively anti-British”, engaging in hit-and-run attacks, killing British military officers and participating in other anti-British activities. In Turkey some Kurds left the ranks of the Turkish army to join the Kurdish army.

After the Treaty of Sèvres, which settled some territories, Sulaymaniya still remained under direct control of the British High Commissioner. After the subsequent penetration of the Turkish "Özdemir" Detachment into the area, an attempt was made by the British to counter this by appointing Sheykh Mahmud, who was returned from his exile, as Governor once again, on 14 September 1922.[6][verification needed]

Sheykh Mahmud revolted again and in November declared himself King of the Kingdom of Kurdistan. Members of his cabinet included Members of his cabinet included:[7]

- Shaikh Qadir Hafeed – Prime Minister

- Abdulkarim Alaka – Finance Minister

- Ahmed Bagy Fatah Bag – Customs Minister

- Hajy Mala Saeed Karkukli – Justice Minister

- Hema Abdullah Agha – Labour Minister. [8]

Barzanji was defeated by the British in July 1924. After the British government finally defeated Sheykh Mahmud, they signed Iraq over to King Faisal I and a new Arab-led government. In January 1926 the League of Nations gave the mandate over the territory to Mandatory Iraq, with the provision for special rights for Kurds.

Sheykh Ahmed's background

After the execution of Shaykh Abd al-Salam in 1914 by Turkish authorities, his 18-year-old brother, Ahmed Barzani, took charge of the tribe.[3] Ahmed, described as “young and unstable”, continued to rule as his brother had, seizing both religious and political power and becoming Shaykh of the region. Shaykh Ahmad's growing religious authority would eventually lead to conflict.[3]

Convinced of Ahmad's divineness, Mulla Abd al-Rahman proclaimed the Shaykh to be “God” and declared himself a prophet.[3] Although Abd al-Rahman was killed by Shaykh Ahmad's brother Muhammad Sadiq, the ideas of Ahmad's divineness spread.[3]

1931 events

Revolt

Shaykh Ahmed's eccentricities would result in his becoming the target of rival tribes by 1931.[3] As the numerous tribal strikes and counter-strikes involving the Barzanis began to plague the countryside, the new Iraqi government, having recently agreed to independence with Britain, attempted to destroy the contentious Barzani tribe.[3] Conflict between the Barzanis and Iraqi forces began in late 1931 and continued through 1932.[3] Commanding Barzani fighters was Shaykh Ahmed's younger brother, Mulla Mustafa Barzani.[3] Mustafa would rise to prominence against the Iraqi forces (who were supplemented by British commanders and the British Royal Air Force).[3]

Links to the Ararat revolt

Ahmed Barzani was the center of focus of British, Iraqi and Turkish discontent. He was very sympathetic to the Kurdish movements in the north led by Khoyboun (the Ararat Revolt). He received many Kurds, who were seeking sanctuary in Barzan, including Kor Hussein Pasha. In September 1930 a Turkish military attaché in Baghdad told Iraq's Prime Minister Nuri Said, “The Turkish military operations in Ararat were very successful.[3] The army will carry similar operations to the west of the Lake of Wan. We expect these operations to come to an end soon. The Turkish army will mobilize along the Iraq-Turkey border if the Iraqi Army moves against the Sheikh Barzan." In fact, Ismet Inönü complained to Nuri Said in Ankara that Sheikh Ahmed was supporting the insurrection in Ararat.[3]

Final accords

By June 1932 Shaykh Ahmed Barzani, his brothers and a small contingent of men were forced to seek asylum in Turkey. Although Ahmad was separated from his followers and sent to Ankara, Mulla Mustafa and Muhammad Sadiq continued to fight Iraqi forces for another year before surrendering. After swearing an oath to King Faysal of Iraq, the Barzanis were allowed to return to Barzan in spring 1933, where they found their “devoutly loyal” forces had kept their organization and weapons.

Aftermath

Eventually Mulla Mustafa was reunited with Shaykh Ahmad Barzani, as the Iraqi government arrested the brothers and exiled them to Mosul in 1933. The two Barzanis were transferred to various cities in Iraq throughout the 1930s and early 1940s. During this time their stops included Mosul, Baghdad, Nasiriya, Kifri and Altin Kopru before finally ending in Sulaymaniya. Meanwhile, back in Barzan, the remaining Barzani tribal fighters were faced with constant pressures of arrest or death.[3]

See also

References

- ^ a b "آغا بطرس: سنحاريب القرن العشرين" (PDF). نينوس نيراري. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-08-12.

- ^ Gloria Center. "Many tribal Kurdish uprisings, aimed at gaining a sort of autonomy, had taken place in Iraq between 1919 and 1932." [1] Archived 2012-09-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Lortz, Michael G. "The Kurdish Warrior Tradition and the Importance of the Peshmerga" Archived October 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Willing to face Death: A History of Kurdish Military Forces - the Peshmerga - from the Ottoman Empire to Present-Day Iraq, 2005-10-28. Chapter 1

- ^ The Kurdish Minority Problem, p.11, Dec. 1948, ORE 71-48, CIA "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-03-08. Retrieved 2012-03-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). - ^ Eskander, S. (2000) "Britain's policy in Southern Kurdistan: The Formation and the Termination of the First Kurdish Government, 1918-1919" in British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies Vol. 27, No. 2. pp. 139-163.

- ^ Khidir, Jaafar Hussein. "The Kurdish National Movement Archived 2012-02-17 at the Wayback Machine", Kurdistan Studies Journal, No. 11, March 2004. Page 14

- ^ Fatah, R. (2006) The Kurdish resistance to Southern Kurdistan annexing with Iraq Archived 2014-04-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Fatah, R. (2006) The Kurdish resistance to Southern Kurdistan annexing with Iraq KurdishMedia.com