Bambara people

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (November 2015) |

ߓߡߊߣߊ߲ | |

|---|---|

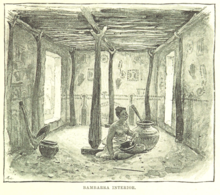

Bambara people in upper Sénégal river valley, 1890. (illustration from Colonel Frey's Côte occidentale d'Afrique, 1890, Fig.49 p.87) | |

| Total population | |

| 5,000,000[1] (2019) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Mali, Guinea, Senegal, Burkina Faso, Niger, Ivory Coast, Mauritania, Gambia | |

| 6,705,796 (33.3%) [2] | |

| 91,071 (1.34%) (1988 census) [3] | |

| 22,583 (1.3%) [4] | |

| Languages | |

| Bambara language, French, Arabic (historically) | |

| Religion | |

| Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Mandinka people, Soninke people, other Mande speaking groups. | |

The Bambara (Template:Lang-bm or ߓߊ߲ߡߊߣߊ߲ Banmana) are a Mandé ethnic group native to much of West Africa, primarily southern Mali, Ghana, Guinea, Burkina Faso and Senegal.[5][6] They have been associated with the historic Bambara Empire. Today, they make up the largest Mandé ethnic group in Mali, with 80% of the population speaking the Bambara language, regardless of ethnicity.

Ethnonym

According to the Encyclopedia of Africa, "Bambara" means "believer" or "infidel"; the group acquired the name because it resisted Islam after the religion was introduced in 1854 by Tukulor conqueror El Hadj Umar Tall."[7]

History

The Bamana originated as a royal section of the Mandinka people. They are founders of the Mali Empire in the 13th Century. Both Manding and Bambara are part of the Mandé ethno-linguistic group, whose divergence is dated to at least about 7,000 years ago,[8] and branches of which are associated with sites near Tichitt (now subsumed by the Sahara in southern Mauritania), where urban centers began to emerge by as early as 2500 BC. By 250 BC, a Mandé subgroup, the Bozo, founded the city of Djenne. Between 300 AD and 1100 AD, the Soninke Mandé dominated the Western Mali, leading the Ghana Empire. When the Nilo-Saharan Songhai Empire dissolved after 1600 AD, many Mandé-speaking groups along the upper Niger river basin turned inward. The Bamana appeared again in this milieu with the rise of a Bamana Empire in the 1740s, when the Mali Empire started to crumble around 1559.

While there is little consensus among modern historians and ethnologists as to the origins or meaning of the ethno-linguistic term, references to the name Bambara can be found from the early 18th century.[9] In addition to its general use as a reference to an ethno-linguistic group, Bambara was also used to identify captive Africans who originated in the interior of Africa perhaps from the upper Senegal-Niger region and transported to the Americas via ports on the Senegambian coast. As early as 1730 at the slave-trading post of Gorée, the term Bambara referred simply to slaves who were already in the service of the local elites or French.[10]

Growing from farming communities in Ouassoulou, between Sikasso and Ivory Coast, Bamana-age co-fraternities (called Tons) began to develop a state structure which became the Bambara Empire and later Mali Empire. In stark contrast to their Muslim neighbors, the Bamana state practised and formalised traditional polytheistic religion, though Muslim communities remained locally powerful, if excluded from the central state at Ségou.[citation needed]

The Bamana became the dominant cultural community in western Mali. The Bambara language, mutually intelligible with the Manding and Dyula languages, has become the principal inter-ethnic language in Mali and one of the official languages of the state alongside French.[citation needed]

Culture

Caste

Traditionally, Mandé society is hierarchal or caste-based, with nobility and vassals. Bamana political order created a small free nobility, set in the midst of endogamous caste and ethnic variation. Both castes and ethnic groups performed vocational roles in the Bamana state, and this differentiation increased with time.

The Maraka merchants developed towns focused first on desert side trade, and latter on large-scale agricultural production using captured slaves. The Jula specialised in long-distance trade, as did Fula communities within the state, who added this to cattle herding. The Bozo ethnicity were created largely out of war captives, and turned by the state to fishing and ferrying communities.[citation needed]

In addition to this, the Bamana maintained internal castes, like other Mandé peoples, with griots, priests, metalworkers, and other specialist vocations remaining endogamous and living in designated areas.[citation needed]

Formerly, like most other African societies, they also held slaves (called "Jonw"/"Jong(o)"), often war prisoners from lands surrounding their territory. With time, and the collapse of the Bamana state, these caste differences have eroded, though vocations have strong family and ethnic correlations.[citation needed]

Religion

Most Bamana today adhere to Islam, but many still practise the traditional rituals, especially in honoring ancestors. This form of syncretic Islam remains rare, even allowing for conversions that in many cases happened in the mid to late 19th century. This recent history, though, contributes to the richness and fame (in the West) of Bamana ritual arts.[citation needed]

Social structure

Bamana share many aspects of broader Mandé social structure. Society is patrilineal and patriarchal. Mandé culture is known for its strong fraternal orders and sororities (Ton) and the history of the Bambara Empire strengthened and preserved these orders. The first state was born as a refashioning of hunting and youth Tons into a warrior caste.[citation needed]

As conquests of their neighbors were successful, the state created the Jonton (Jon = slave/kjell-slave), or slave warrior caste, replenished by warriors captured in battle. While slaves were excluded from inheritance, the Jonton leaders forged a strong corporate identity. Their raids fed the Segu economy with goods and slaves for trade, and bonded agricultural laborers who were resettled by the state.[citation needed]

Ton societies

The Bamana have continued in many places their tradition of caste and age group inauguration societies, known as the Tons. While this is common to most Mandé societies, the Ton tradition is especially strong in Bamana history. Tons can be by sex (initiation rites for young men and women), age (the earlier young men's Soli ton living separately from the community and providing farm labor prior to taking wives), or vocation (the farming Chi Wara Ton or the hunters Donzo Ton). While these societies continue as ways of socialising and passing on traditions, their power and importance faded in the 20th century.[citation needed]

Art

The Bamana people adapted many artistic traditions. Artworks were created both for religious use and to define cultural and religious difference. Bamana artistic traditions include pottery, sculpture, weaving, iron figures, and masks. While the tourist and art market is the main destination of modern Bamana artworks, most artistic traditions had been part of sacred vocations, created as a display of religious beliefs and used in ritual.[citation needed]

Bamana forms of art include the n’tomo mask and the Tyi Warra. The n’tomo mask was used by dancers at male initiation ceremonies. The Tyi Warra (or ciwara) headdress was used at harvest time by young men chosen from the farmers association. Other Bamana statues include fertility statues, meant to be kept with the wife at all times to ensure fertility, and statues created for vocational groups such as hunters and farmers, often used as offering places by other groups after prosperous farming seasons or successful hunting parties.[citation needed]

Each special creative trait a person obtained is seen as a different way to please higher spirits. Powers throughout the Bamana art-making world are used to please the ancestral spirits and show beauty in what they believed in.[citation needed]

Notable people

- Aya Nakamura, French-Malian Singer

- Alassane Pléa

- Kaladian Coulibaly, King of Segou

- Mamary Coulibaly, Emperor

- Kalidou Koulibaly, Senegalese footballer

- Kafoumba Coulibaly

- Rokia Traoré, Malian musician

- Sammy Traoré

- Bertrand Traoré

- Alain Traoré

- Kandia Traoré

- Lassina Traoré

See also

References

- ^ Bambara at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2019)

- ^ "Mali". www.cia.gov/. Retrieved November 19, 2020.

- ^ Chiffres de la Division de la Statistique de Dakar cités dans Peuples du Sénégal, Éditions Sépia, 1996, p. 182

- ^ "Distribution of the Gambian population by ethnicity 1973,1983,1993,2003 and 2013 Censuses - GBoS". www.gbosdata.org. Archived from the original on 2021-11-19. Retrieved 2021-06-17.

- ^ "Tribal African Art Bambara (Bamana, Banmana)". Zyama.com - African Art Museum. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- ^ den Otter, Elisabeth; Esther A. Dagan (1997). Puppets and masks of the Bamana and the Bozo (Mali) - from The Spirit's Dance in Africa. Galerie Amrad African Arts Publications.

- ^ Editors: Appiah, Anthony; Gates, Henry Louis, Encyclopedia of Africa, Volume 1, Oxford University Press (2010), p. 150, ISBN 9780195337709 [1]

- ^ D.F. McCall, "The Cultural Map and Time Profile of the Mande Speaking Peoples," in C.T. Hodge (ed.). Papers on the Manding, Indiana University, Bloomington, 1971.

- ^ Labat, Jean-Baptiste (1728). Nouvelle Relation de l'Afrique Occidentale 3 Vol. Paris.

- ^ Bathily, Abdoulaye (1989). Les Ports de l'Or Le Rouyaume de Galam (Sénégal) de l'Ere Musulmane au Temps de Nègriers (VIIIe-XVIIe Siècle). Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Further reading

- Imperato, Pascal James (1970). "The Dance of the Tyi Wara". African Arts. 4 (1). African Arts, Vol. 4, No. 1: 8–13, 71–80. doi:10.2307/3334470. JSTOR 3334470.

- Le Barbier, Louis (1918). Études africaines : les Bambaras, mœurs, coutumes, religions (in French). Paris. p. 42.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - McNaughton, Patrick R. (1979). "Bamana Blacksmiths". African Arts. 12 (2). African Arts, Vol. 12, No. 2: 65–66, 68–71, 91. doi:10.2307/3335488. JSTOR 3335488.

- Pharr, Lillian E. (1980). Chi-Wara headdress of the Bambara: A select, annotated bibliography. Washington, D.C.: Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution. OCLC 8269403.

- Roberts, Richard L. (1987). Warriors, Merchants and Slaves: The State and the Economy in the Middle Niger Valley 1700-1914. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1378-2.

- Roberts, Richard L. (1980). "Production and Reproduction of Warrior States: Segu Bambara and Segu Tokolor". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 13 (3). The International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol. 13, No. 3: 389–419. doi:10.2307/218950. JSTOR 218950.

- Tauxier, Louis (1942). Histoire des Bambara (in French). Paris: P. Geuthner. p. 226.

- Wooten, Stephen R. (2000). "Antelope Headdresses and Champion Farmers: Negotiating Meaning and Identity through the Bamana Ciwara Complex". African Arts. 33 (2). African Arts, Vol. 33, No. 2: 18–33, 89–90. doi:10.2307/3337774. JSTOR 3337774.

- Zahan, Dominique (1980). Antilopes du soleil: Arts et rites agraires d'Afrique noire (A. Schendl ed.). Paris: Edition A. Schendl. ISBN 3-85268-069-7.