Negro Sanhedrin

The Negro Sanhedrin was a national "All-Race Conference" held in the American city of Chicago, Illinois, from February 11 to 15, 1924. The gathering was attended by 250 delegates representing 61 trade unions, civic groups, and fraternal organizations in a short-lived attempt to forge a national program protecting the legal rights of African-American tenant farmers and wage workers and extending the scope of civil rights.

History

Background

The idea for a national conference bringing together representatives of African-American organizations came in the spring of 1923, following Congressional defeat of the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill.[1] William Monroe Trotter of the National Equal Rights League (NERL) of Boston is credited with originating the idea for assembly of a national council of prominent black leaders.[1] This idea was passed along to president of the NERL, Matthew A. N. Shaw, who issued a formal invitation to five like-minded organizations asking for their support.[1]

Among the groups initially solicited was the African Blood Brotherhood (ABB), a radical semi-underground organization affiliated with the Workers Party of America.[1] Head of the ABB, Cyril Briggs, took the initiative in coordinating such a gathering, initially touted by him as a "United Front Negro Conference of Civil Rights Organizations."[1] On March 24, 1923, a formal document was signed by representatives of the six organizations pledging their support of the conference.[1] In addition to the ABB and NERL, other groups lending their formal support included the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the International Uplift League, the Friends of Freedom, and the National Race Congress.[1]

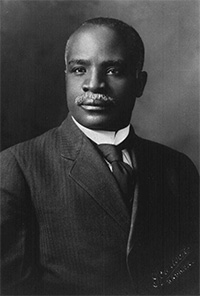

Dean Kelly Miller of Howard University, formally representing the National Race Congress, was chosen as head of the arrangements committee, with Cyril Briggs of the ABB continuing to handle day to day organizational tasks as secretary.[1] Nearly a year of meetings and organizational outreach followed, with the moderate Miller cementing ties with mainstream community and fraternal organizations. It was Miller who chose the name for the gathering,[1] the "Sanhedrin," a phrase originating in the Biblical first book of Maccabees[2] and referring to a supreme council of the Hebrew people.[3]

Convention

The Sanhedrin assembled in Chicago on February 11, 1924, attended by 250 delegates representing 61 organizations.[4]

The gathering was attended by organizations ranging across the ideological spectrum, from conservative civic groups to the African Blood Brotherhood.[5] A considerable number of professionals, scholars, and businesspeople were included among the delegates, who hailed from no fewer than 20 American states.[1] As a result, the gathering was far from radical, with the convention electing Kelly Miller its chairman following a short debate — a decision bitterly opposed by the radical caucus of delegates, which included Briggs and his Workers Party comrades, Lovett Fort-Whiteman, and Otto Huiswoud.[4]

Program

Lovett Fort-Whiteman spoke on the floor of the convention for the agenda of radical delegates, headed by Communists and the ABB.[4] He urged the adoption of a program calling for an end to racial segregation in the housing market, termination of colonialism in Africa, legally binding contracts to protect tenant farmers, abolition of anti-miscegenation laws, and diplomatic recognition of Soviet Russia by the United States government, among other things.[6] Resolutions condemning the American Federation of Labor for allowing its affiliated unions the freedom to exclude black workers from membership and calling for African Americans to join the Communist-sponsored Farmer-Labor Party were prepared.[7]

Convention chairman Miller short-circuited the agenda of the radicals, however, using his power to appoint an official of the Chicago Chamber of Commerce as head of the Sanhedrin's Labor Committee.[7] This forced the ABB and its allies to bring its proposed resolutions for action directly from the floor of the gathering, a process which ended in failure for its resolutions dealing with school segregation, opposing the Ku Klux Klan, and seeking recognition of Soviet Russia.[8]

Those resolutions which were passed were severely tempered from the preferred wording of the radicals, including a comparatively mild rebuke of labor union locals for exclusion of black members rather than ringing condemnation of the leadership of the American Federation of Labor[7] and opining in favor of equal pay for workers without respect to race and organized financial assistance to the struggling agricultural workers being crushed by the agricultural depression that gripped the nation.[8]

The Sanhedrin was adjourned sine die on February 15, 1924.

Legacy

The Negro Sanhedrin was the first national gathering of black Americans at which members of the Communist movement openly participated.[6] In the view of one scholar, the Sanhedrin represented "a grand opportunity for mainstream black organizations and black radicals to set aside their differences and formulate a program of mutual benefit."[9] In this the Sanhedrin was a great failure, with the factional activities of the Communists in Chicago deeply resented and the organization banned from a subsequent and final gathering held in Washington, D.C.[8]

Nor would the Sanhedrin movement be a successful or lasting vehicle for the coordination of activity by the myriad of mainstream black organizations, with momentum dissipating almost immediately after the close of the Chicago gathering.

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Joyce Moore Turner with W. Burghardt Turner, Caribbean Crusaders and the Harlem Renaissance. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2005; pg. 113.

- ^ 1 Maccabees ch. 11, verse 23; ch. 12, verse 6. Cited in Robert A. Hill (ed.), The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers: Volume 5, September 1922–August 1924. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1986; p. 558, fn. 1.

- ^ Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, Defying Dixie: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights, 1919-1950. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2008; p. 40.

- ^ a b c Gilmore, Defying Dixie, p. 41.

- ^ Gilmore, Defying Dixie, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b Gilmore, Defying Dixie, pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b c Gilmore, Defying Dixie, p. 42.

- ^ a b c Turner with Turner, Caribbean Crusaders and the Harlem Renaissance, p. 114.

- ^ Herb Boyd, "Radicalism and Resistance: The Evolution of Black Radical Thought," The Black Scholar, vol. 28, no. 1 (Spring 1998), p. 47.

Further reading

- Bernard Eisenberg, "Kelly Miller: The Negro Leader as a Marginal Man," Journal of Negro History, vol. 45, no. 3 (July 1960), pp. 182–197. In JSTOR

- C. Alvin Hughes, "The Negro Sanhedrin Movement," Journal of Negro History, vol. 69, no. 1 (Winter 1984), pp. 1–13. In JSTOR

- Kelly Miller, The Negro Sanhedrin: A Call to Conference. Washington, DC: Murray Brothers, 1923.

- Kelly Miller, "The Negro Sanhedrin: A Clearing House and Union of Organizations," The Afro-American [Baltimore], vol. 32, no. 15 (December 28, 1923), p. 16.

- J. A. Zumoff, "The American Communist Party and the 'Negro Question' from the Founding of the Party to the Fourth Congress of the Communist International." Journal for the Study of Radicalism, vol. 6, no. 2 (Fall 2012), pp. 53–89.

- W. D. Wright, "The Thought and Leadership of Kelly Miller," Phylon, vol. 39, no. 2 (2nd Quarter 1978), pp. 180–192. In JSTOR