Nickeline

| Nickeline | |

|---|---|

| |

| General | |

| Category | Arsenide mineral |

| Formula (repeating unit) | nickel arsenide (NiAs) |

| Strunz classification | 2.CC.05 |

| Crystal system | Hexagonal |

| Crystal class | Dihexagonal dipyramidal (6/mmm) H-M symbol: (6/m 2/m 2/m) |

| Space group | P63/mmc |

| Unit cell | a = 3.602 Å, c = 5.009 Å; Z = 2 |

| Identification | |

| Color | Pale copper red with blackish tarnish. white with strong yellowish pink hue on polished section strongly anisotropic |

| Crystal habit | Massive columnar to reniform, rarely as distorted, horizontally striated, {1011} terminated crystals |

| Twinning | On {1011} producing fourlings |

| Cleavage | {1010} Imperfect, {0001} Imperfect |

| Fracture | Conchoidal |

| Tenacity | Brittle |

| Mohs scale hardness | 5 - 5.5 |

| Luster | metallic |

| Streak | brownish black |

| Diaphaneity | Opaque |

| Specific gravity | 7.8 |

| Pleochroism | Strong (reflected light) |

| Fusibility | 2 |

| Other characteristics | garlic odor on heating |

| References | [1][2][3] |

Nickeline or niccolite is a mineral consisting of nickel arsenide (NiAs) containing 43.9% nickel and 56.1% arsenic.

Small quantities of sulfur, iron and cobalt are usually present, and sometimes the arsenic is largely replaced by antimony. This last forms an isomorphous series with breithauptite (nickel antimonide).

Etymology and history

When, in the medieval German Erzgebirge, or Ore Mountains, a red mineral resembling copper-ore was found, the miners looking for copper could extract none from it, as it contains none; worse yet, the ore also sickened them. They blamed a mischievous sprite of German mythology, Nickel (similar to Old Nick) for besetting the copper (German: Kupfer).[4] This German equivalent of "copper-nickel" was used as early as 1694 (other old German synonyms are Rotnickelkies and Arsennickel).

In 1751, Baron Axel Fredrik Cronstedt was attempting to extract copper from kupfernickel mineral, and obtained instead a white metal that he called after the spirit, nickel.[5] In modern German, Kupfernickel and Kupfer-Nickel designates the alloy Cupronickel.

The names subsequently given to the ore, nickeline from F. S. Beudant, 1832, and niccolite, from J. D. Dana, 1868, refer to the presence of nickel; in Latin, niccolum.

In 1971, the International Mineralogical Association recommended use of the name nickeline rather than niccolite.[6]

Preparation of NiAs

The main compound within nickeline, nickel arsenide (NiAs), can be prepared by direct combination of the elements:

Ni(s) + As(s) → NiAs(s)[7]

Occurrence

Nickeline is formed by hydrothermal modification of ultramafic rocks and associated ore deposits, and may be formed by replacement of nickel-copper bearing sulfides (replacing pentlandite, and in association with copper arsenic sulfides), or via metasomatism of sulfide-free ultramafic rocks, where metasomatic fluids introduce sulfur, carbonate, and arsenic. This typically results in mineral assemblaged including millerite, heazelwoodite and metamorphic pentlandite-pyrite via sulfidation and associated arsenopyrite-nickeline-breithauptite.

Associated minerals include: arsenopyrite, barite, silver, cobaltite, pyrrhotite, pentlandite, chalcopyrite, breithauptite and maucherite. Nickeline alters to annabergite (a coating of green nickel arsenate) on exposure to moist air.

Most of these minerals can be found in the areas surrounding Sudbury and Cobalt, Ontario. Other localities include the eastern flank of the Widgiemooltha Dome, Western Australia, from altered pentlndite-pyrite-pyrrhotite assemblages within the Mariners, Redross and Miitel nickel mines where nickeline is produced by regional Au-As-Ag-bearing alteration and carbonate metasomatism. Other occurrences include within similarly modified nickel mines of the Kambalda area.

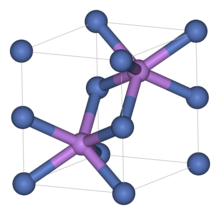

Crystal structure

The unit cell of nickeline is used as the prototype of a class of solids with similar crystal structures. It consists of arsenic atoms in a distorted hexagonal close-packed structure with nickel atoms in "octahedral" sites, which in NiAs have distorted to become trigonal prismatic.[8] Compounds adopting the NiAs structure are generally the chalcogenides, arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of transition metals. [citation needed]

The following are the members of the nickeline group:[2]

- Achavalite: FeSe

- Breithauptite: NiSb

- Freboldite: CoSe

- Kotulskite: Pd(Te,Bi)

- Langistite: (Co,Ni)As

- Nickeline: NiAs

- Sobolevskite: Pd(Bi,Te)

- Sudburyite: (Pd,Ni)Sb

Economic importance

Nickeline is rarely used as a source of nickel due to the presence of arsenic, which is deleterious to most smelting and milling techniques. When nickel sulfide ore deposits have been altered to produce nickeline, often the presence of arsenic renders the ore uneconomic when concentrations of As reach several hundred parts per million. However, arsenic bearing nickel ore may be treated by blending with 'clean' ore sources, to produce a blended feedstock which the mill and smelter can handle with acceptable recovery.

The primary problem for treating nickeline in conventionally constructed nickel mills is the specific gravity of nickeline versus that of pentlandite. This renders the ore difficult to treat via the froth flotation technique. Within the smelter itself, the nickeline contributes to high arsenic contents which require additional reagents and fluxes to strip from the nickel metal.

References

- ^ http://rruff.geo.arizona.edu/doclib/hom/nickeline.pdf Handbook of Mineralogy

- ^ a b http://www.mindat.org/min-2901.html Mindat.org

- ^ http://webmineral.com/data/Nickeline.shtml Webmineral data

- ^ Chambers Twentieth Century Dictionary, p888, W&R Chambers Ltd, 1977.

- ^ Weeks, Mary Elvira (1932). "The discovery of the elements: III. Some eighteenth-century metals". Journal of Chemical Education. 9 (1): 22. Bibcode:1932JChEd...9...22W. doi:10.1021/ed009p22.

- ^ "International Mineralogical Association: Commission on New Minerals and Mineral Names" (PDF). Mineralogical Magazine. 38 (293): 102–105. 1971. Bibcode:1971MinM...38..102.. doi:10.1180/minmag.1971.038.293.14.

- ^ Shriver and Atkins' Inorganic Chemistry (Fifth ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. 2009. p. 383. ISBN 978-1-4292-1820-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Inorganic Chemistry by Duward Shriver and Peter Atkins, 3rd Edition, W.H. Freeman and Company, 1999, pp.47,48.

- Dana's Manual of Mineralogy ISBN 0-471-03288-3