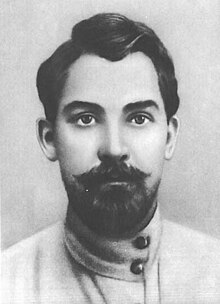

Mykola Shchors

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2013) |

Mykola Shchors | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | June 6, 1895 Snovsk, Chernigov Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | August 30, 1919 (aged 24) near Biloshytsya, Volyn Governorate, Ukraine |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | Russian Imperial Army Red Army |

| Years of service | 1914–1919 |

| Rank | Comdiv |

| Unit | Bohun Regiment |

| Commands | Bohun Regiment 2nd Brigade (1st Ukrainian Soviet Division) 44th Rifle Division |

| Battles / wars | World War I Ukrainian–Soviet War |

| Awards | Honorary weapon |

| Signature | |

Mykola Oleksandrovich Shchors (Template:Lang-uk; 6 June [O.S. 25 May] 1895 – 30 August 1919) was a Red Army commander, member of the Russian Communist Party, renowned for his personal courage[by whom?] during the Russian Civil War and sometimes being called the Ukrainian Chapayev. In 1918–1919 he fought against the new established Ukrainian government of the Ukrainian People's Republic. Later he commanded the Bohunsky regiment, brigade, 1st Soviet Ukrainian division and 44th rifle division against head of the Ukrainian People's Republic Symon Petliura and his Polish allies. Shchors was slain in battle.

Early life

Nikolay Shchors was born in the village of Snovsk of Gorodnya uyezd (Chernigov Governorate) into a family of kulaks. His father Aleksandr Nikolayevich, a locomotive engineer, according to the official Soviet historiography, arrived from a town of Stowbtsy (Minsk Governorate) "in search of better life" to Snovsk where he was able to build his own house (since August 1939 – a memorial museum). Nikolay Shchors was the oldest child amongst his other siblings: Konstantin (1896–1979), Akulina (1898–1937), Yekaterina (1900–1984), Olga (1900–1985).[1] In 1905 Nikolai enrolled into a parish church school. In 1906 giving a birth to another child Nikolai's mother, Aleksandra Mikhailovna Tabelchuk, died due to loss of blood. About six months after the death of his wife, Nikolai's father remarried, this time to Maria Konstantinovna Podbelo. Aleksandr and Maria had five more children: Grigori, Zinaida, Boris, Raisa, and Lidia. In 1909 Nikolai Shchors graduated from his church school.

World War I

In 1910 Shchors enrolled into a military medical college (uchilishche) in Kiev, which was established in 1833 and was considered one of the best.[by whom?][citation needed] The school was usually attended by the children of retired soldiers. Among some of the graduates were Ivan Ohienko, Ostap Vyshnya, Mykhailo Donets, and others. The state scholarship allowed a free enrollment which had to be repaid by volunteer service in the army. Shchors graduated from the school in 1914 and upon receiving the rank of a junior physician assistant was transferred to the Vilna Military District. In September 1914 when the Russian Empire was drawn into World War I, Shchors went to the front lines as part of the 3rd Light Artillery Division near Vilno where he served as a medical assistant. During one of the battles, he was wounded and evacuated from the area to recover.

Upon recovery in 1916, the 21-year-old Shchors enrolled into the accelerated four-month program at Vilnius Military School that had been evacuated to Poltava in 1915. The school was preparing unter-officers and praporshchiks who specialized in tactics, navigation, and trench warfare. Upon graduation in May 1916 Shchors at first was sent as a praporshchik to a reserve regiment in the city of Simbirsk and only in September of that same year was he transferred to the 335th Anapa Regiment of the 84th Infantry Division (South-Western Front). For his courage and tactical knowledge, Shchors soon was promoted to a rank of junior lieutenant (podporuchik). However, the trench warfare left a mark on his health when he was diagnosed with tuberculosis and once again was sent to the rear.

Revolutionary period

Upon his recovery on December 30, 1917 from the Simferopol City hospital Shchors was released from the military service due to health problems and at the beginning of 1918 he arrived back to his home village of Snovsk. Accidentally, since January 1918 the government of the Soviet Russia started military aggression against the Ukrainian People's Republic accusing the latter in sabotaging the frontlines with the Russian Imperial Army and impeding military maneuvers of the Red Army. In less than three weeks, the Red Guards occupied most of the Left-bank Ukraine. Right before the elections to the Ukrainian Constituent Assembly, the Red Army of Mikhail Muravyov conquered Kiev. The government of Ukraine was appealing to foreign powers to provide military aid and finally finding it in the Central Powers that were eager to cooperate to destroy the Russian Revolution.

Sometime after the arrival to his native land, he became acquainted with the chairman of a local Cheka Fruma Rostova (real name Khaikina) whom he married in the fall of 1918. Fruma in her early 20s was conducting so-called "cleaning" (zachistka) in the region, an ambiguous Cheka term. Simultaneously around that time, Shchors also was enrolled into the Russian Communist Party (bolshevik). In March–April, 1918 he commanded a joint detachment of Novozybkovsky district that fought against the Ukrainian Army and German army as a part of the 1st Insurgent Division. In September 1918 he formed the 1st Bohun Regiment and lead it against occupying German forces and the externally supported Ukrainian State army. In November 1918 he took command of the 2nd brigade of the 1st Ukrainian Soviet division (Bohun and Tarashcha regiments) and conquered Chernihiv, Kiev and Fastiv from the Ukrainian Directory. On February 5, 1919 Shchors was appointed mayor of Kiev.

Between March 6 and August 15, 1919 Shchors again led the 1st Ukrainian Soviet division in its impetuous offensive and took control of Zhytomyr, Vinnytsia, and Zhmerynka from Ukrainian People's Republic head Symon Petliura. Then he decisively defended the main forces of Petliura near Sarny - Rivne - Brody - Proskuriv.

In summer 1919 the Polish army began a major offensive. Shchors attempted to hold the line near Sarny - Novohrad-Volynsky - Shepetivka, but was forced to retreat east by the vastly more numerous, more trained, and materially more resourced Polish army. The 1st Ukrainian Soviet division was merged with the 44th Rifle Division and Shchors was appointed its new commander. Under his command the division defended the Korostensky railroad junction allowing the evacuation of Kiev and the escape of the southern group of the 12th Army from encirclement.

According to an official version, while fighting in the front lines of Bohun regiment, Shchors was killed in very obscure circumstances near the Biloshytsi village in Zhytomyr Oblast on August 30, 1919. However, according to the version of Ukrainian student of local history Holovatyi, Shchors was killed by a commissar of the 12th Division near Korosten after the decision of Revolutionary military council.[2] Shchors was buried in Samara, far from the battlefield, for unclear reasons.

Shchors' widow's maiden name was Fruma Khaikina. Her revolutionary name was Rostova, after the heroine of War and Peace, Natasha Rostova. Their daughter married noted Soviet physicist Isaak Khalatnikov.

In popular culture

In 1939 Aleksandr Dovzhenko made a film called Shchors, which was awarded the State Prize of the Soviet Union in 1941. Yevgeny Samoylov played Shchors in the movie. A famous Soviet song, "Song about Shchors", was composed by Matvey Blanter, author of "Katyusha", and the poet Mikhail Golodny.

References

- ^ (in Ukrainian) Shchors City official website

- ^ Holovatyi, Mykhailo. 200 streets of Ivano-Frankivsk. "Lileya NB". Ivano-Frankivsk, 2010. ISBN 978-966-668-231-7, ISBN 978-966-668-149-5.

External links

![]() Media related to Nikolay Shchors at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Nikolay Shchors at Wikimedia Commons