Domenico Lalli

Domenico Lalli | |

|---|---|

Engraved portrait of Lalli published in 1818 | |

| Born | Sebastiano Biancardi 27 March 1679 |

| Died | 9 October 1741 (aged 62) |

| Known for | Opera librettist |

Sebastiano Biancardi (27 March 1679 – 9 October 1741),[a] known by the pseudonym Domenico Lalli, was an Italian poet and librettist. Amongst the many libretti he produced, largely for the opera houses of Venice, were those for Vivaldi's Ottone in villa and Alessandro Scarlatti's Tigrane. A member of the Accademia degli Arcadi, he also wrote under his arcadian name "Ortanio". Lalli was born and raised in Naples as the adopted son of Fulvio Caracciolo but fled the city after being implicated in a bank fraud. After two years wandering about Italy in the company of Emanuele d'Astorga, he settled in Venice in 1710 and worked as the "house poet" of the Grimani family's theatres for the rest of his career. In addition to his stage works, Lalli published several volumes of poetry and a collection of biographies of the kings of Naples. He died in Venice at the age of 62.

Biography

Early life

Modern accounts of Lalli's life prior to arriving in Venice are largely based on a biography included in a book of poetry which he published in 1732. The biography was written by the Venetian poet Giovanni Boldini who collaborated with Lalli on several of his libretti.[3] A further biography of Lalli by Andrea Mazzarella[b] was published in 1818 in Biografia degli uomini illustri del Regno di Napoli.

Sebastiano Biancardi, as he was then known, was born in Naples to Caterina (née Amendola) and Michele Biancardi. His father's family were originally merchants from Milan who had moved to Naples in the Middle Ages. At the age of 11 months, he was adopted by Fulvio Caracciolo, a member of a Neapolitan noble family and the second son of the Duke of Martina. Under Caracciolo he was educated in law and literature and was exposed to many prominent Neapolitan intellectuals, such as Giambattista Vico, who frequented the house. His adoptive father died in 1692, leaving Biancardi as his sole heir. At the age of 18, with both his natural and adoptive parents dead, he married Giustina Baroni. According to a late 18th-century biography of Lalli by Eustachio D'Afflitto,[c] she was the sister of the Bishop of Calvi.[7] By 1700, Biancardi had gone through most of his inheritance and with an ever-growing family to support took up a post as chief cashier at the bank of the Santissima Annunziata.[8][9]

Flight from Naples

In 1706 a large amount of money was found to be missing from the Santissima Annunziata's funds, and Biancardi was eventually suspected of embezzlement. Leaving his wife and 13 children behind, he fled Naples for Rome.[9] There he befriended Emanuele d'Astorga, a composer and son of a Sicilian aristocrat, who used Biancardi's poems as texts for several of his cantatas and serenatas.[10] Over the next two years Biancardi and d'Astorga wandered through Italy together. Left destitute after they were robbed by their servant in Genoa, they managed to scrape together some money when d'Astorga set a libretto for an impresario of the opera house there. They then headed for Venice, but fearful that their servant was still pursuing them they changed their names. D'Astorga became "Giuseppe del Chiaro". Biancardi became "Domenico Lalli", the name by which he was known for the rest of his career and which appears in the Venetian records of his second marriage.[8][11]

On their way to Venice, they were arrested and imprisoned for not having passports and passing themselves off as Romans. They were only freed after Lalli wrote a letter to the Governor of Milan, recounting the robbery by their servant and their subsequent misfortunes. They arrived in Venice in 1709 and made the acquaintance of the influential poet and librettist Apostolo Zeno. This was accomplished by d'Astorga writing a fake letter to Zeno purporting to be from Baron d'Astorga in Palermo and recommending to him two young men in need of patronage—"Giuseppe del Chiaro, maestro di cappella", and "Domenico Lalli, professor of literature and lute player". Lalli and d'Astorga then spent some time in Mantua under their new identities, but remained in constant fear that visitors from Rome would recognize them. D'Astorga left for Barcelona when he was offered a post at the court of Charles III, and Lalli returned to Venice.[8][11]

Venetian career

According to Mazzarella's 1818 biography of Lalli, on his return to Venice he recited some of his poetry to Zeno and asked for his opinion. Zeno recognized the poems which had been published several years earlier in Naples and said that while the poetry had merit, Lalli was either a plagiarist or was actually Sebastiano Biancardi. At this point, Lalli revealed his true identity to Zeno and confessed to the reason he had left Naples. Zeno took him under his wing and introduced him to the Grimani family who hired Lalli to assist in the management of their theatres (Teatro San Samuele and Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo) and to re-work older libretti for new productions.[1][8]

He eventually became the Grimani "house poet". Musicologist and historian Reinhard Strohm, described Lalli's role in the Venetian theatres, and especially those of the Grimani family, as "resourceful poet and hack, theatre manager and career-maker." According to Strohm, he proved particularly useful in obtaining the latest libretti written by Metastasio for Rome, slightly revising them and having them set by another composer for a rival production in Venice. In one case, he managed to do this even before the Rome premiere. Metastasio's Ezio had its official premiere in Rome on 26 December 1728 with music by Pietro Auletta. However, a setting by Nicola Porpora of the slightly altered libretto had premiered at the Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo a month earlier.[9] The Venetian version carried a dedication written by Lalli to Count Harrach, the Austrian viceroy of Naples.[12]

Lalli's first original opera libretto, L'amor tirannico ("Tyrannical Love") was performed with music by Francesco Gasparini in 1710 at the Teatro San Cassiano in Venice. L'amor tirranico had considerable success and was also performed in Milan in 1713 and again in Venice in 1722. His comic opera Elisa with music by Giovanni Maria Ruggieri followed in 1711. According to Giovanni Carlo Bonlini, it was the first opera buffa to be presented in Venice.[13][d] In the ensuing years he went on to produce the libretti for numerous opere serie, including at least five for Vivaldi,[e] three for Albinoni and two for Alessandro Scarlatti. Writing in 1811, Pietro Napoli-Signorelli[f] described Tigrane, the first libretto Lalli wrote for Scarlatti, as "full of oddities and fantasy" and displaying "great inventiveness in its design".[8] Lalli became very well connected to figures in the intellectual and theatrical life of Venice and to the aristocrats who patronized its theatres. Zeno jokingly referred to the gatherings at Lalli's house as the "Accademia Lalliana" ("Lallian Academy").[8] Lalli was also a member of an actual academy, the Accademia degli Arcadi. The academy's pan pipe symbol appears on the title pages of some of his published poetry, and two of his intermezzi (La cantatrice and Il tropotipo) were published under his arcadian name "Ortanio".

In 1723, in addition to his work for the Venetian theatres, Lalli became the court poet for Maximilian Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria and later his son Carl Albert.[17] He wrote numerous poems and several libretti for royal celebrations in Bavaria, including I veri amici with music by Albinoni for the wedding celebrations of Carl Albert to Maria Amalia of Austria in 1722. The opera was performed again in Venice the following year, in a slightly revised version.[9] He also worked with Antonio Caldara, who was the maestro di cappella of the Prince-Archbishop of Salzburg, writing the libretti for two of Caldara's operas presented at the court theatre there. Apart from his libretti, Lalli also published poetry and prose works in Venice under his real name. He brought out a collection of twenty sonnets in praise of Francesco del Giudice in 1715 and two volumes of his collected poetry, Rime di Bastian Biancardi and Rime berniesche di Bastian Biancardi in 1732. Most of the work in the 1732 collections was new, but they also included a few poems previously published in Naples, including one on the death of his adoptive father, Fulvio Caracciolo.[18][19][20] Lalli's Italian translation of Rousset de Missy's history of Russia during the reign of Catherine the Great, Memorie del regno di Catterina imperadrice e sovrana di tutta la Russia, was published in 1730.

Final years

By the mid-1730s, Lalli's career as a librettist was waning, and he was eventually replaced by Goldoni as the director of the Grimani theatres. After the death of his first wife, he had married a Venetian woman, Barbara Pazini, who provided him with many more children to support. He eked out a living writing dedications to illustrious theatre patrons on re-worked libretti, brought out collections of Biblical proverbs and parables translated into verse, and with the help of his close friend and fellow Neapolitan exile Pietro Giannone wrote a collection of biographies of the kings of Naples which he published in 1737. Goldoni's contemporary, Gasparo Gozzi, lamented that Lalli's financial predicament was commonplace for those working in the arts in 18th-century Venice and described him as a man "who was born rich and died a poet".[21] Lalli himself alluded to these problems in several poems in his 1732 Rime berniesche.[3]

The restoration of the Bourbon king Charles VII to the throne of Naples in 1735, raised Lalli's hopes of being able to return to his native city. In 1738 he wrote the libretto for Partenope nell'Adria, a serenata composed by Ignazio Fiorillo celebrating the marriage of Charles to Maria Amalia of Saxony and described himself on the title page as the King's "fedelissimo vassallo" ("most faithful vassal"). The following year he published a continuation of his biographies of the kings of Naples concentrating on the "gloriosa persona di Don Carlo di Borbone" ("the glorious figure of Don Charles of Bourbon"). He repeatedly petitioned the king for a royal pardon allowing him to return to Naples but without success. Lalli died in poverty in Venice at the age of 62 and was buried in the Church of Santa Maria Formosa.[1][8]

Libretti

According to Reinhard Strohm, at least 22 original or significantly re-worked opera libretti can be attributed to Lalli.[9] Apart from his 1711 comic opera Elisa and four comic intermezzi, the remainder of the opera libretti attributed to him are all in the opera seria and dramma per musica genres. Lalli also wrote texts and libretti for several musical works in other genres: cantatas, serenatas, and azioni sacri (stage works on religious subjects and precursors of the oratorio).

The attribution of some of Lalli's opera libretti is complicated by the fact that from 1728 he often collaborated with Giovanni Boldini. In some cases the libretti are listed as jointly authored. In other cases there is disagreement as to whether Lalli or Boldini was the author, e.g. the libretto for L'Issipile set by Giovanni Porta in 1732 and that for Artaserse set by Adolph Hasse in 1730.[13] Some libretti by Lalli and/or Boldini were primarily re-workings of libretti by other authors although with the text much changed, as was the case with Hasse's 1730 Artaserse based on a libretto by Metastasio.[22] Lalli's own libretti were often reworked to a greater or lesser extent by other librettists, including his Amor tirranico originally set by Francesco Gasparini in 1710 and reworked with minor changes by Nicola Haym for Handel's Radamisto.[23] Others were set by multiple composers under different titles. His libretto, Il gran Mogol, was set by 5 different composers (including Vivaldi) between 1714 and 1733.[24]

Opera

- L'amor tirranico, music attributed to Francesco Gasparini, Teatro San Cassiano, Venice, 1710[13]

- Elisa, music attributed to Giovanni Maria Ruggieri, Teatro Sant'Angelo, Venice, 1711[13]

- Ottone in villa, music by Antonio Vivaldi, Teatro delle Grazie, Vicenza, 1713[25]

- Il gran Mogol, music by Francesco Mancini, Teatro San Bartolomeo, Naples, December 1713.[26][27]

- Re-set as Argippo by Giovanni Porta, Teatro San Cassiano, Venice, autumn 1717.[24][28]

- Libretto revised by Claudio Nicola Stampa, set by Vivaldi as Argippo, RV 697-A, Theater am Kärntnertor, Vienna, 1730 (music lost).[29]

- Variant of the previous libretto, Argippo, RV 697-B, set by Vivaldi, Sporck Theater, Prague, autumn 1730 (music lost).[24][29][30]

- Pasticcio, Argippo, RV Anh. 137: Vivaldi's setting of some of the text based on Lalli's libretto has been preserved.[29]

- Pisistrato, music by Leonardo Leo, Teatro San Bartolomeo, Naples, 1714[g]

- Tigrane, music by Alessandro Scarlatti, Teatro San Bartolomeo, Naples, 1715.[10]

- L'amor di figlio non conosciuto, music by Tomaso Albinoni, Teatro San'Angelo, Venice, 1716[13]

- Arsilda, regina di Ponto, music by Antonio Vivaldi, Teatro San'Angelo, Venice, 1716[13]

- Farnace, music by Carlo Francesco Pollarolo, Teatro San Cassiano, Venice, 1718[13]

- Il Lamano , music by Michelangelo Gasparini, Teatro San Giovanni Crisostomo, Venice, 1718[13]

- Il Cambise, music by Alessandro Scarlatti, Teatro San Bartolomeo, Naples, 1719[8]

- La Candace, o siano Li veri amici, music by Antonio Vivaldi, court theatre, Mantua, 1720[31]

- Filippo re di Macedonia, music by Antonio Vivaldi, Teatro Sant'Angelo, Venice, 1720[13]

- Gli eccessi dell'infedeltà, music by Antonio Caldara, court theatre, Salzburg, 1720[32]

- Il Farasmane, music by Giuseppe Maria Orlandini, Teatro Formagliari, Bologna, 1720[33]

- Gli eccessi della gelosia, music by Tomaso Albinoni, Teatro Sant'Angelo, Venice, 1722[13]

- I veri amici, music by Tomaso Albinoni, court theatre, Munich, 1722 (commissioned for the wedding celebrations of Carl Albert of Bavaria to Maria Amalia of Austria)[9]

- Camaide, imperatore della China, music by Antonio Caldara, court theatre, Salzburg, 1722 (Lalli also wrote two comic intermezzi for this performance, La marchesina di Nanchin and Il conte di Pelusio.)[34]

- Damiro e Pitia, music by Nicola Porpora, court theatre, Munich, 1724 (commissioned to celebrate the name day of Maximilian Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria)[35]

- La Mariane, music by Giovanni Porta, Teatro Sant'Angelo, Venice 1725[36]

- Ulisse, music by Giovanni Porta, Teatro Sant'Angelo, Venice 1725[36]

- Imeneo in Atene, music by Nicola Porpora, Teatro San Samuele, Venice, 1726[9]

- Turia Lucrezia, music by Antonio Pollarolo, Teatro Sant'Angelo, Venice 1725[36]

- L' Epaminonda, music by Pietro Torri, court theatre, Munich, 1727 (commissioned to celebrate the birth of Maximilian Joseph of Bavaria)[37]

- Nicomede, music by Pietro Torri, court theatre, Munich, 1728 (commissioned to celebrate the arrival of Count Palatine Francis Louis of Neuburg in Munich)[37]

- Edippo, music by Pietro Torri, court theatre, Munich, 1729 (commissioned to celebrate the birthday of Maria Amalia)[37]

- Argene, music by Leonardo Leo, Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo, Venice 1728 (the opera proved very popular and played throughout the carnival season. Leo composed a new setting of it for performance in Naples in 1731).[35]

- Il Tamese, music by Francesco Feo, Teatro San Bartolomeo, Naples, 1729 (performed with the three-part dramatic intermezzo, Il vedovo, also by Lalli)[38]

- Dalisa (after Nicolò Minato), music by Johann Adolf Hasse, Teatro San Samuele, Venice, 1730[35]

Other genres

- Calisto in orsa (serenata for four voices), composer unknown, Venice 1714[39]

- Scherza di fronda (cantata), music by Antonio Vivaldi, Venice, circa 1721[40]

- La senna festeggiante (serenata for three voices), music by Antonio Vivaldi, Venice, 1726 (According to Vivaldi scholar Michael Talbot, the context of the performance is unclear—either in honour of the name day of the King of France in August, or the arrival in Venice of the French ambassador, Jacques-Vincent Languet in November.)[15]

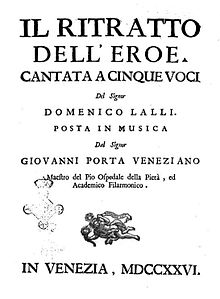

- Il ritratto dell'eroe (cantata for five voices), music by Giovanni Porta, Venice, 1726 (performed in celebration of the return to Venice of Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni)[41]

- La Fenice (cantata for three voices), music by Giovanni Battista Costanzi, Venice 1726[42]

- L' Abramo (azione sacra), composer unknown, Venice 1733[43]

- Il peccato originale (azione sacra), composer unknown, Venice 1736[8]

- Partenope nell'Adria (serenata), music by Ignazio Fiorillo, Venice, 1738 (performed in celebration of the marriage of Charles VII to Maria Amalia of Saxony, commissioned by the Ambassador of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.)[44]

- L' Abel (azione sacra), composer unknown, Venice, 1738[8]

- Decreto del fato (serenata for 4 voices), music by Domenico Paradies, Spanish Embassy, Venice, 1740 (performed in celebration of the marriage of Prince Philip of Spain)[13]

Notes

- ^ Lalli's first name at birth "Sebastiano" is sometimes rendered in its Neapolitan form "Bastiano" or "Bastian". At least one 19th-century source gives his complete birth name as "Niccola Sebastiano Biancardi". A volume of his poetry published in Florence in 1708 gives his name as "Niccolò Bastiano Biancardi".[1][2]

- ^ Tommaso Andrea Mazzarella (1764–1823) was an Italian poet and jurist active in the short-lived Parthenopean Republic which led to his exile from Naples between 1799 and 1804.[4]

- ^ Eustachio D'Afflitto (1742–1787) was a Neapolitan professor of history and a member of the Dominican Order. His biography of Biancardi/Lalli published in Memorie degli scrittori del Regno di Napoli also contains information provided by one of his sons, Domenico Biancardi, who in 1784 was an army commandant. It is unclear whether this was a son from Lalli's first or second marriage.[5][6]

- ^ Giovanni Carlo Bonlini (1673–1731) was a Venetian literary figure whose Le Glorie della Poesia e della Musica contenute nell'esatta notizia de' Teatri della città di Venezia was an annotated chronological list of all operas performed in Venice between 1637 and 1730.[14]

- ^ Problems of attribution have made the exact number unclear. Lalli may have written (or co-written) as many as seven libretti set by Vivaldi.[15]

- ^ Pietro Napoli-Signorelli (1731–1815) was a Neapolitan literary figure and critic. Amongst his works was Vicende della coltura nelle due Sicilie, a five volume cultural history of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.[16]

- ^ According to Strohm, the libretto for Pisistrato was first printed in Venice in 1711 for a performance at the Teatro al Dolo, composer unknown.[9]

References

- ^ a b c Mazzarella, Andrea (1818). "Bastiano Biancardi". Biografia degli uomini illustri del Regno di Napoli. Vol. 5, pp. 37–40. Nicola Gervasi (in Italian)

- ^ Biancardi, Sebastiano (1708). All'altezza reale di Cosimo III, gran duca di Toscana. Rime di Niccolò Bastiano Biancardi. Vincenzio Vangelisti (in Italian)

- ^ a b Tavazzi, Valeria (2014). Carlo Goldoni dal San Samuele al "Teatro comico", pp. 49–81. Accademia University Press (in Italian)

- ^ Minieri-Riccio, Camillo (1844). Memorie storiche degli scrittori nati nel regno di Napoli, p. 212. Aquilla (in Italian)

- ^ Nicolini, Fausto (1932/1992). La giovinezza di Giambattista Vico, p. 140. Il Mulino (in Italian)

- ^ Cassani, Cinzia (1985). "D'Afflitto, Eustachio". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 31. Online version retrieved 25 March 2015 (in Italian)

- ^ D'Afflitto, Eustachio (1794). "Biancardi (Sebastiano)". Memorie degli scrittori del Regno di Napoli, Vol, 2, pp. 118–125. Stamperia Simoniana (in Italian)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (1968). "Biancardi, Sebastiano". Vol. 10. Treccani. Online version retrieved 15 March 2015 (in Italian).

- ^ a b c d e f g h Strohm, Reinhard (1995). "The Neapolitans in Venice" in Ian Fenlon et al. (eds.) Con Che Soavità: Studies in Italian Opera, Song, and Dance, 1580–1740, pp. 255–257, 269. Oxford University Press

- ^ a b Sadie, Julie Anne (1998). Companion to Baroque Music, pp. 78, 487. University of California Press

- ^ a b Boldini, Giovanni (1732). "Compendio della Vita del Sig. Bastian Bìiancardi Napoletano, detto Domenico Lallí" in Rime di Bastian Biancardi. Giuseppe Lovisa

- ^ Servizio Bibliotecario Nazionale (Venice catalog). Document VEA1176146T: Ezio: Dramma Per Musica. Retrieved 23 March 2015 (in Italian).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Selfridge-Field, Eleanor (2007). A New Chronology of Venetian Opera and Related Genres, 1660–1760, pp. 298, 306, 324, 328, 334, 338, 343, 433, 615. Stanford University Press

- ^ Piscitelli Gonnelli, Giovanna (1971). "Bonlini, Giovanni Carlo". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 12. Treccani. Online version retrieved 15 March 2015 (in Italian).

- ^ a b Talbot, Michael (2011). The Vivaldi Compendium, pp. 104–106, 165, 231–232. Boydell Press

- ^ Gillio, Pier Giuseppe (2012). "Napoli Signorelli. Pietro". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 77. Treccani. Online version retrieved 20 March 2015 (in Italian).

- ^ Warren, F.M. (May 1888). "Italian Literature in Bavaria". Modern Language Notes, pp. 282–284.

- ^ Biancardi, Sebastiano (1732). Rime di Bastian Biancardi napoletano chiamato Domenico Lalli tra gl'Arcadi Ortanio. Con la vita del auttore. Giuseppe Lovisa (in Italian)

- ^ Biancardi, Sebastiano (1732). Rime berniesche di Bastian Biancardi napoletano chiamato Domenico Lalli tra gl'Arcadi Ortanio. Giuseppe Lovisa (in Italian)

- ^ Biancardi, Sebastiano (1715). Sonetti in lode dell'eminentiss. e reverendiss. signore D. Francesco Giudice (in Italian)

- ^ Monnier, Philippe (1910). Venice in the Eighteenth Century, p. 77. Chatto & Windus

- ^ Hansell, Sven (2001). "Artaserse (ii). Grove Music Online. Retrieved 14 March 2015 (subscription required for full text).

- ^ Parker, Mary Ann (2005). G. F. Handel: A Guide to Research. p. 159. Routledge

- ^ a b c Freeman, Daniel E. (1992). The Opera Theater of Count Franz Anton Von Sporck in Prague Stuyvesant, N.Y.: Pendragon Press. ISBN 0945193173, p. 166

- ^ Strohm, Reinhard (1985). Essays on Handel and Italian Opera, p. 141. Cambridge University Press

- ^ Il gran Mogol : drama per musica / di Domenico Lalli ; da rappresentarsi nel Teatro di S. Bartolomeo nel giorno 26. di decembre 1713 ; dedicato alla grandezza impareggiabile dell'Eccellentiss. signor conte VVirrico di Daun, vicerè, e capitan generale in questo regno di Napoli, &c. at Trove website.

- ^ Carlo Antonio de Rosa marchese di Villarosa (1840). Memorie dei compositori di musica del regno di Napoli: raccolte dal marchese di Villarosa. Naples: Stamperia reale, p. 110.

- ^ Talbot 2011, p. 92.

- ^ a b c Talbot 2011, p. 25.

- ^ Freeman, Daniel E. (1995). "Antonio Vivaldi and the Sporck Theater in Prague", pp. 117–140 in Janáček and Czech Music: Proceedings of The International Conference (St. Louis 1988). Pendragon Press. ISBN 094519336X, pp. 122, 129.

- ^ Colas, Damien and Di Profio, Alessandro (2009). D'une scène à l'autre, Vol.2, pp. 104–106. Editions Mardaga

- ^ Kirkendale, U. (1972). "Caldara, Antonio". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 16. Treccani. Online version retrieved 24 March 2015 (in Italian).

- ^ Giuntini, Francesco (2013). "Orlandini, Giuseppe Maria". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 79. Treccani. Online version retrieved 24 March 2015 (in Italian).

- ^ Ward, Adrienne (2010). Pagodas in Play: China on the Eighteenth-century Italian Opera Stage, pp. 90–95. Bucknell University Press

- ^ a b c Strohm, Reinhard (1997). Dramma Per Musica: Italian Opera Seria of the Eighteenth Century, pp. 76, 79. Yale University Press

- ^ a b c Talbot, Michael (2002). The Business of Music, p. 55. Liverpool University Press

- ^ a b c Basso, Alberto (1996). Musica in scena, Vol. 3, p. 40. UTET

- ^ Servizio Bibliotecario Nazionale (central catalog). Document MUS\0288844: Il Tamese. Retrieved 25 March 2015 (in Italian).

- ^ Servizio Bibliotecario Nazionale (central catalog). Document MUS\0323439: Calisto in orsa. Retrieved 25 March 2015 (in Italian).

- ^ Talbot, Michael (2006). The Chamber Cantatas of Antonio Vivaldi, p. 72. Boydell Press

- ^ Markstrom, Kurt Sven (2007). The Operas of Leonardo Vinci, Napoletano, p. 257. Pendragon Press

- ^ Lopriore, Maria (1984). "Costanzi, Giovanni Battista". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 30. Treccani. Online version retrieved 25 March 2015 (in Italian).

- ^ Servizio Bibliotecario Nazionale (central catalog). Document MILE\054292: L' Abramo. Retrieved 25 March 2015 (in Italian).

- ^ Isman, Fabio (ed.) (2010). Venzialtrove: Almanacco della presenza di Venezia nel mondo, p. 20. Fondazione Venezia. Retrieved 25 March 2015 (in Italian).

Sources

- Talbot, Michael (2011). "Dictionary". The Vivaldi Compendium. Boydell Press. pp. 17–200. ISBN 9781843836704.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Brizzi, Bruno (1980). "Domenico Lalli librettista di Vivaldi?". Vivaldi veneziano europeo, pp. 183–204. Leo S. Olschki. OCLC 490153057

External links

- Combined list of works by Domenico Lalli/Sebastiano Biancardi held in Italian libraries (annotated)

Media related to Domenico Lalli at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Domenico Lalli at Wikimedia Commons