Titus Oates

Titus Oates | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 15 September 1649 |

| Died | 13 July 1705 (aged 55) London, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | Priest |

| Known for | Fabricating the Popish Plot |

| Parents |

|

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1675–76[1] |

| Rank | Naval chaplain |

Titus Oates (15 September 1649 – 12/13 July 1705) was an English priest who fabricated the "Popish Plot", a supposed Catholic conspiracy to kill King Charles II.

Early life

Titus Oates was born at Oakham in Rutland. His father Samuel (1610-1683), of a family of Norwich ribbon-weavers,[2][3] was a graduate of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, and became a minister who moved between the Church of England (sometime rector of Marsham, Norfolk)[4] and the Baptists; he became a Baptist during the Puritan Revolution,[5]: 5 rejoining the established church at the Restoration, and was rector of All Saints' Church at Hastings (1666–74).[5]: 3 [1]

Oates was educated at Merchant Taylors' School and other schools. At Cambridge University, he entered Gonville and Caius College in 1667 but transferred to St John's College in 1669;[6] he left later the same year without a degree.[1] A less than astute student, he was regarded by his tutor as "a great dunce", although he did have a good memory.[5]: 5 [3] At Cambridge, he also gained a reputation for homosexuality and a "Canting Fanatical way".[1]

By falsely claiming to have a degree, he gained a licence to preach from the Bishop of London.[1] On 29 May 1670 he was ordained as a priest of the Church of England. He was vicar of the parish of Bobbing in Kent, 1673–74, and then curate to his father at All Saints', Hastings. During this time Oates accused a schoolmaster in Hastings of sodomy with one of his pupils, hoping to get the schoolmaster's post. However, the charge was shown to be false and Oates himself was soon facing charges of perjury, but he escaped jail and fled to London.[1] In 1675 he was appointed as a chaplain of the ship HMS Adventure in the Royal Navy.[7]: 54–55 Oates visited English Tangier with his ship, but was accused of buggery, which was a capital offence, and spared only because of his clerical status.[7]: 54–55 He was dismissed from the Navy in 1676.

In August 1676, Oates was arrested in London and returned to Hastings to face trial for his outstanding perjury charges, but he escaped a second time and returned to London.[1] With the help of the actor Matthew Medburne[Note 1] he joined the household of the Catholic Henry Howard, 7th Duke of Norfolk as an Anglican chaplain to those members of Howard's household who were Protestants. Although Oates was admired for his preaching, he soon lost this position.[1]

On Ash Wednesday in 1677 Oates was received into the Catholic Church.[3] Oddly, at the same time he agreed to co-author a series of anti-Catholic pamphlets with Israel Tonge, whom he had met through his father Samuel, who had once more reverted to the Baptist doctrine.[8]

He is described by John Dryden in Absalom and Achitophel thus—[5]: 7

Sunk were his eyes, his voice was harsh and loud,

Sure signs he neither choleric was nor proud:

His long chin proved his wit, his saint-like grace

A church vermilion and a Moses' face.

Contact with the Jesuits

Oates was involved with the Jesuit houses of St Omer in France and the Royal English College at Valladolid in Spain. Oates was admitted to the training course for the priesthood in Valladolid through the support of Richard Strange, head of the English Province, despite a lack of basic competence in Latin.[3] He later claimed, falsely, that he had become a Catholic Doctor of Divinity. His ignorance of Latin was quickly exposed, and his frequently blasphemous conversation and attacks on the British monarchy shocked both his teachers and the other students. Thomas Whitbread, the new Provincial, took a much firmer line with Oates than had Strange and, in June 1678, expelled him from St Omer.[7]: 58

When he returned to London, he rekindled his friendship with Israel Tonge. Oates explained that he had pretended to become a Catholic to learn about the secrets of the Jesuits and that, before leaving, he had heard about a planned Jesuit meeting in London.

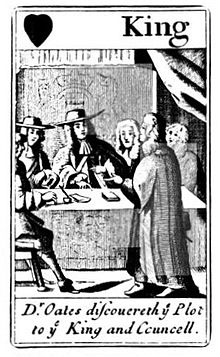

Fabricating the Popish Plot

Oates and Tonge wrote a lengthy manuscript that accused the Catholic Church authorities in England of approving the assassination of Charles II. The Jesuits were supposedly to carry out the task. In August 1678, King Charles was warned of this alleged plot against his life by the chemist Christopher Kirkby, and later by Tonge. Charles was unimpressed, but handed the matter over to one of his ministers, Thomas Osborne, Earl of Danby; Danby was more willing to listen and was introduced to Oates by Tonge.

The King's Privy Council questioned Oates. On 28 September, Oates made 43 allegations against various members of Catholic religious orders—including 541 Jesuits—and numerous Catholic nobles. He accused Sir George Wakeman, Queen Catherine of Braganza's doctor, and Edward Colman, the secretary to Mary of Modena, Duchess of York, of planning to assassinate Charles.

Although Oates may have selected the names randomly, or with the help of the Earl of Danby, Colman was found to have corresponded with a French Jesuit, Father Ferrier, who was confessor to Louis XIV, which was enough to condemn him. Wakeman was later acquitted. Despite Oates' unsavoury reputation, his confident performance and superb memory made a surprisingly good impression on the Council. When he named "at a glance" the alleged authors of five letters supposedly written by leading Jesuits, the Council were "amazed". As Kenyon remarks, it is surprising that it did not occur to the Council that this was useless as evidence if Oates had written all the letters himself.[7]: 79

Others whom Oates accused included Dr William Fogarty, Archbishop Peter Talbot of Dublin, Samuel Pepys MP, and John Belasyse, 1st Baron Belasyse. With the help of Danby, the list grew to 81 accusations. Oates was given a squad of soldiers and he began to round up Jesuits, including those who had helped him in the past.

On 6 September 1678, Oates and Tonge had approached an Anglican magistrate, Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey, and had sworn an affidavit before him detailing their accusations. On 12 October, Godfrey disappeared, and five days later his dead body was found in a ditch at Primrose Hill; he had been strangled and run through with his own sword. Oates subsequently exploited this incident to launch a public campaign against the "Papists" and alleged that the murder of Godfrey had been the work of the Jesuits.

On 24 November 1678, Oates claimed the Queen was working with the King's physician to poison the King. Oates enlisted the aid of "Captain" William Bedloe, who was ready to say anything for money. The King personally interrogated Oates and caught him out in a number of inaccuracies and lies. In particular Oates unwisely claimed to have had an interview with the Regent of Spain, Don John, in Madrid: the King who had met Don John at Brussels during his Continental exile, pointed out that Oates' hopelessly inaccurate description of his appearance made it clear that he had never seen him. The King ordered his arrest. However, a few days later, with the threat of a constitutional crisis, Parliament forced the release of Oates, who soon received a state apartment in Whitehall and an annual allowance of £1,200.

Oates was heaped with praise. He asked the College of Arms to check his lineage and produce a coat of arms for him and subsequently received the arms of a family that had died out. Rumours surfaced that Oates was to be married to a daughter of Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury.

After nearly three years and the execution of at least 15 innocent men, opinion began to turn against Oates. The last high-profile victim of the climate of suspicion was Oliver Plunkett, Roman Catholic Archbishop of Armagh, who was hanged, drawn and quartered on 1 July 1681. William Scroggs, the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, began to declare more people innocent, as he had done in the Wakeman trial, and a backlash against Oates and his Whig supporters took place.

Aftermath

On 31 August 1681, Oates was told to leave his apartments in Whitehall, but he remained undeterred and even denounced the King and his Catholic brother, the Duke of York. He was arrested for sedition, sentenced to a fine of £100,000 and imprisoned.

When the Duke of York acceded to the throne in 1685 as James II, he had Oates retried, convicted and sentenced for perjury, stripped of clerical dress, imprisoned for life, and to be "whipped through the streets of London five days a year for the remainder of his life."[9] Oates was taken from his cell wearing a hat with the text "Titus Oates, convicted upon full evidence of two horrid perjuries" and put into the pillory at the gate of Westminster Hall (now New Palace Yard), where passers-by pelted him with eggs. The next day he was pilloried in London and the third day was stripped, tied to a cart, and whipped from Aldgate to Newgate. The next day, the whipping resumed. The presiding judge at his trial was Judge Jeffreys, who stated that Oates was a "shame to mankind", ignoring the fact that he himself had helped to condemn innocent people on Oates' perjured evidence. So severe were the penalties that it has been suggested that the aim was to kill Oates by ill-treatment, as Jeffreys and his fellow judges openly regretted that they could not impose the death penalty in a case of perjury.

Oates spent the next three years in prison. In 1689, upon the accession of the Protestant William of Orange and Mary, he was pardoned and granted a pension of £260 a year, but his reputation did not recover. The pension was later suspended, but in 1698 was restored and increased to £300 a year. Oates died on 12 or 13 July 1705, by then an obscure and largely forgotten figure.

In popular culture

Francis Barlow made a comic strip about the Popish Plot and Oates in 1682 named A True Narrative of the Horrid Hellish Popish-Plot, which is generally considered the earliest example of a signed balloon comic strip.[10]

Oates was played by Nicholas Smith in the 1969 BBC TV serial The First Churchills. In Charles II: The Power and The Passion (2003), Eddie Marsan played Oates.

Notes

- ^ Medburne was arrested under suspicion of involvement in the Popish Plot, he died in Newgate Prison in 1680.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Oates, Titus". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20437. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, vol. 41, Nichols-O'Dugan, ed. Sidney Lee, Macmillan & Co., 1895, p. 296

- ^ a b c d Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, vol. 41, Nichols-O'Dugan, ed. Sidney Lee, Macmillan & Co., 1895, p. 296

- ^ a b c d Pollock, John (1903). The Popish Plot: a study in the history of the reign of Charles II. London: Duckworth and Co.

- ^ "Oates, Titus (OTS667T)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ a b c d Kenyon, J. P. (2000) [1972]. The Popish Plot. Reissue of the 1984 Pelican paperback. Phoenix Press.

- ^ Alan Marshall, ‘Tonge, Israel (1621–1680)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004

- ^ Pincus, Steve (2009). 1688: The First Modern Revolution. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 153.

- ^ "Francis Barlow". Lambiek Comiclopedia. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

External links

- Titus Oates at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Jane Lane [Elaine (Kidner) Dakers], Titus Oates, Westport, Connecticut : Greenwood Press, 1971.

- Emma Robinson, Whitefriars, or, The Days of Charles the Second : an historical romance, London : H. Colburn, 1844 [G. Routledge, 1851].

- Use dmy dates from April 2012

- 1649 births

- 1705 deaths

- 17th-century LGBT people

- Alumni of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge

- Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge

- Anti-Catholic propagandists

- Anti-Catholicism in England

- British male criminals

- English perjurers

- English military chaplains

- Gay men

- History of Catholicism in the United Kingdom

- LGBT people from England

- LGBT Anglican clergy

- People associated with the Popish Plot

- People educated at Merchant Taylors' School, Northwood

- People from Oakham

- Recipients of English royal pardons

- Royal Navy chaplains