Western riding

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2011) |

Western riding is considered a style of horse riding which has evolved from the ranching and welfare traditions which were bought to the Americans by the Spanish Conquistadors, as well as both equipment and riding style which evolved to meet the working needs of the cowboy in the American West. At the time, American cowboys had to work long hours in the saddle and often over rough terrain, sometimes having to rope a cattle using a lariat, also known as a lasso.[1] Because of the necessity to control the horse with one hand and use a lariat with the other, western horses were trained to neck rein, that is, to change direction with light pressure of a rein against the horse's neck. Horses were also trained to exercise a certain degree of independence in using their natural instincts to follow the movements of a cow, thus a riding style developed that emphasized a deep, secure seat, and training methods encouraged a horse to be responsive on very light rein contact.

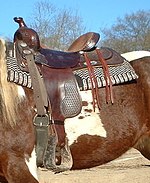

Though there are significant differences in equipment, there are fewer differences between English and Western riding than appear at first glance. When comparing Western riding or English riding, the first, and biggest difference is the saddles used. The Western saddle is designed to be larger and heavier than an English saddle, which is designed to be smaller and lighter. The western saddle allows the weight of the rider to be spread over a larger area of the horse's back which makes it more comfortable, especially for long days chasing cows. The English saddle, however, is designed to allow the rider to have closer contact with the horse's back (Wilson, 2003).[2]

Another difference is that English riding involves the rider having direct contact with the horse's mouth via reins and the reins are used as part of an “aid.” In western riding, however, horses are mainly ridden with little to no contact with the riders using their seat, weight and neck reining to give aid or instructions in direction, etc., to the horse. In both Western and English riding, however, involve the rider sitting tall and straight in the saddle with their legs hanging naturally against the horse's sides as well as their arms relaxed and against their side, but not flapping, which is frowned against (Wilson, 2003).[2]

"Western Riding" is also the name for a specific event within western competition where a horse performs a pattern that combines trail and reining elements.

Tack and equipment

Today's western saddles have been greatly influenced by the Spanish Vaquero who were Cowboys. When the first saddle was developed, it didn't have a horn which was later invented by the Spanish and Mexican vaqueros (Kelly, 2011).[3] The needs of the cowboy's job required different tack than was used in "English" disciplines. Covering long distances, and working with half-wild cattle, frequently at high speeds in very rough, brushy terrain, meant the ever-present danger of a rider becoming unseated in an accident miles from home and support. Thus, the most noticeable equipment difference is in the saddle, which has a heavy and substantial tree (traditionally made of wood) to absorb the shock of roping. The western saddle features a prominent pommel topped by a horn that came about through trial and error for developing an efficient way of towing livestock (Kelly, 2011).[3] The horn is the easiest way to identify a western saddle. It allows the rider support and can be used for a lasso or other equipment (Gen, 2011).[4] The western saddle also consist of a deep seat and a high cantle. Depending on the local geography, tapaderos ("taps") cover the front of the stirrups to prevent brush from catching in the stirrups. Cowboy boots have somewhat more pointed toes and higher heels than a traditional work boot, modifications designed to prevent the rider's foot from slipping through the stirrup during a fall and being dragged.

To allow for communication with the horse even with a loose rein, the bridle also evolved. The biggest difference between "English" and "Western" bridles is the bit. Most finished "Western" horses are expected to eventually perform in a curb bit with a single pair of reins that has somewhat longer and looser shanks than the curb of an English Double bridle or a pelham bit. Different types of reins have developed over the years. Split reins, which are the most commonly used type of rein in the western industry, Mecates, which are a single rein that are used on California hackamores, Romal reins, also known as romals, which is a type of rein that has two distinct and balanced parts which are the reins and romal connected with a short strap and roping reins which are a single rein that varies in length and is often used in roping and other speed events (Tack, 2017).[5] Young horses are usually started under saddle with either a simple snaffle bit, or with the classic tool of the vaquero, the bosal-style hackamore.

Rider attire

The clothing of the Western rider differs from that of the "English" style dressage, hunt seat or Saddle seat rider. Practical Western attire consists of a long-sleeved work shirt, denim jeans, boots, and a wide-brimmed cowboy hat. Usually, a rider wears protective leather leggings called "chaps" (from the Spanish chaparajos; often pronounced "shaps") to help the rider stick to the saddle and to protect the legs when riding through brush. Clean, well-fitting work clothing is the usual outfit seen in rodeo, cutting and reining competitions, especially for men, though sometimes in brighter colors or finer fabrics.

Show equipment

Some competitive events may use flashier equipment. Unlike the English traditions where clothing and tack is quiet and unobtrusive, Western show equipment is intended to draw attention. Saddles, bits and bridles are frequently ornamented with substantial amounts of silver. The rider's shirt is often replaced with a jacket, and women's clothing, in particular, may feature vivid colors and even, depending on current fads, rhinestones or sequins. Hats and chaps are often color-coordinated, spurs and belt buckles are often silver-plated, and women's scarf pins and, when worn, men's bolo ties are also ornamented with silver or even semi-precious gemstones.

Western competitive events

Competition for western riders at horse shows and related activities include in the following events:

- Western pleasure - the rider must show the horse together with other horses in an arena at a walk, jog (a slow, controlled trot), and lope (a slow, controlled canter). In some breed competitions, a judge may ask for an extended canter and/or a hand gallop, and, less often, an extension of the jog. The horse must remain under control on a loose rein, with low head carriage, the rider directing the horse with nearly invisible aids and minimal interference.

- Reining - considered by some the "dressage" of the western riding world, with FEI-recognized status as a new international discipline at the World Equestrian Games. Reining is judged based on the horse and rider's ability to perform the maneuverers in an assigned pattern. The maneuvers consist of stops, which consist of the horse staying mobile in the front while the hind legs “slide” and the horse lowing its head and neck, spins, which consist of the horse planting one back foot and pivoting on it at a fast speed, circles, which are do be done at the lope, both large fast and small slow, rollbacks, which consist of the horse coming to a stop and then performing a 180-degree turn to the outside and loping off right away and finally, lead changes, which consist of the horse changing leads in the middle of the arena (Fabus and Hartman, 2016).[6]

- Cutting - this event highlights the "cow sense" prized in stock horses. The horse and rider select and separate a cow (or steer) out of small herd of 10–20 animals. When the cow tries to return to the herd, the rider relaxes the reins and leaves it entirely to the horse to keep the cow from returning to the herd. Depending on the level of competition, one to three judges award points to each competitor.

- Working cow horse - also called Reined cow horse. A judged competition that is something of a cross between cutting and reining. A horse and rider teamwork a single cow in an arena, making the cow move in a directed fashion through several maneuvers.

- Ranch horse: An event that, depending on breed sanctioning organization, tests multiple categories used by working ranch horses: Ranch riding, which is similar to western pleasure; Ranch trail, testing tasks performed during ranch work, often judged on natural terrain rather than in an arena; Ranch Cutting, judged the same as a cutting event; Working ranch horse, combining Reining, Roping, and working cow horse; and ranch conformation and is judged like a halter class.

- "Western Riding" Western Riding is a class that judges horses on a pattern, evaluating smooth gaits, flying lead changes, responsiveness to the rider, manners, and disposition.

- Team penning: a timed event in which a team of 3 riders must select 3 to 5 marked steers out of a herd and drive them into a small pen. The catch: riders cannot close the gate to the pen till they have corralled all the cattle (and only the intended cattle) inside. The fastest team wins, and teams exceeding a given time limit are disqualified. A related event is Ranch sorting

- Trail class: in this event, the rider has to maneuver the horse through an obstacle course in a ring. Horses must cross bridges, logs and other obstacles; stand quietly while a rider waves a flapping object around the horse; sidepass (to move sideways), often with front and rear feet on either side or a rail; make 90 and 180 degree turns on the forehand or haunches, back up, sometimes while turning, open and close a gate while mounted, and other maneuvers relevant (distantly) to everyday ranch or trail riding. While speed isn't judged, horses have a limited amount of time to complete each obstacle and can be penalized for refusing an obstacle or exceeding the allotted time.

- Halter - also sometimes called "conformation" or "breeding" classes, the conformation of the horse is judged, with emphasis on both the movement and build of the horse. The horse is not ridden, but is led, shown in a halter by a handler controlling the horse from the ground using a lead rope.

- Halter Showmanship, also called (depending on region, breed, and rule book followed) Showmanship at Halter, Youth Showmanship, Showmanship in-hand or Fitting and Showmanship - In showmanship classes the performance of the handler is judged, as well as the cleanliness and grooming of horse, equipment and handler's attire, with the behavior of the horse also considered part of the handler's responsibility. The competitor is judged on his or her ability to fit and present the halter horse to its best advantage. The horse is taken through a short pattern where the horse and handler must set up the horse correctly at a standstill and exhibit full control while at a walk, jog, turning and in more advanced classes, pivoting and backing up. Clothing of the handlers tends to parallel that of western pleasure competition. Halters are leather ornamented with silver. Showmanship classes are popular at a wide range of levels, from children who do not yet have the skill or confidence to succeed in riding events, to large and competitive classes at the highest levels of national show competition.

Western equitation

Western equitation (sometimes called western horsemanship, stock seat equitation, or, in some classes, reining seat equitation) competitions are judged at the walk, jog, and lope in both directions. Riders must sit to the jog and never post.

In a Western equitation class a rider may be asked to perform a test or pattern, used to judge the rider's position and control of the horse. Tests may be as simple as jogging in a circle or backing up, or as complex as a full reining pattern, and may include elements such as transitions from halt to lope or lope to halt, sliding stops, a figure-8 at the lope with simple or flying change of lead, serpentines at the lope with flying changes, the rein back, a 360-degree or greater spin or pivot, and the rollback.

Riders must use a western saddle and a curb bit, and may only use one hand to hold the reins while riding. Two hands are allowed if the horse is ridden in a snaffle bit or hackamore, which are only permitted for use on "junior" horses, defined differently by various breed associations, but usually referring to horses four or five years of age and younger. Horses are not allowed to wear a noseband or cavesson, nor any type of protective boot or bandage, except during some tests that require a reining pattern.

Riders are allowed two different styles of reins: 1) split reins, which are not attached to one another, and thus the rider is allowed to place one finger between the reins to aid in making adjustments; and 2) "romal reins," which are joined together and have a romal (a type of long quirt) on the end, which the rider holds in their non-reining hand, with at least 16 inches of slack between the two, and the rider is not allowed to place a finger between the reins.

The correct position for this discipline, as in all forms of riding, is a balanced seat. This is seen when a bystander can run an imaginary straight line that passes through the rider's ear, shoulder, hip, and heel. This means the rider's feet and legs must hang directly in balance so that the heel hits this line, with heels down. The rider should also be sitting as straight as possible, but with their hips under their body, sitting firmly on their seat bones, not sitting on one's crotch with an arched back. The rider should have their weight sunk into their seat and distributed through their legs. The rider's shoulders should be rolled back and their chin up to show that they are looking forward.

The western style is seen in a long stirrup length, often longer than even that used by dressage riders, an upright posture (equitation riders are never to lean forward beyond a very slight inclination), and the distinctive one-handed hold on the reins. The reining hand should be bent at the elbow, held close to the rider's side, and centered over the horse's neck, usually within an inch of the saddle horn. Due to the presence of the saddle horn, a true straight line between rider's hand and horse's mouth is usually not possible. Common faults of western riders include slouching, hands that are too high or too low, and poor position, particularly a tendency to sit on the horse as if they were sitting in a chair, with their feet stuck too far forward. While this "feet on the dashboard" style is used by rodeo riders to stay on a bucking horse, it is in practice an ineffective way to ride.

See also

- Australian rodeo

- Cowboy

- Cutting (sport)

- Equitation

- Halter (horse show)

- Horse showmanship

- Reining

- Rodeo

- Western pleasure

- Working cow horse

- Western saddle

References

- ^ Buck, L (2019). "The History of Western Riding Competitions". Esri.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Wilson, J (2003). "English Versus Western Riding- What's the Difference?". Equisearch.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Kelly, S (2011). "The Origin of the American Saddle". TheFencePost.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Gen, A (2011). "The Parts of a Western Saddle". SaddleOnline.com.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Dennis Moreland Tack (2017). "Split Reins, Roping Reins, 2 Rein and Romals: Which Reins Are Right for You?". QuarterHorseNews.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Fabous, K. and Hartman, K (2016). "How do you judge reining?". Michigan State University; MSU Extension.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: url-status (link)

- Strickland, Charlene. Competing in Western Shows & Events. Storey Books, div. Storey Communications, 1998. ISBN 1-58017-031-5

- Williamson, Charles O. Breaking and Training the Stock Horse

External links

- American Quarter Horse Association

- United States Equestrian Federation

- New Zealand Equestrian Federation