Sea pen

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2007) |

| Sea pen Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

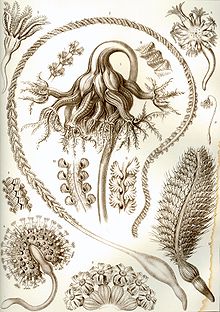

| "Pennatulida" from Ernst Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur, 1904 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria |

| Class: | Octocorallia |

| Order: | Pennatulacea Verrill, 1865 |

| Families | |

|

See text | |

Sea pens are colonial marine cnidarians belonging to the order Pennatulacea. There are 14 families within the order; 35 extant genera, and it is estimated that of 450 described species, around 200 are valid.[1] Sea pens have a cosmopolitan distribution, being found in tropical and temperate waters worldwide, as well as from the intertidal to depths of more than 6100m.[1] Sea pens are grouped with the octocorals ("soft corals"), together with sea whips or gorgonians.

Although the group is named for its supposed resemblance to antique quill pens, only sea pen species belonging to the suborder Subselliflorae live up to the comparison. Those belonging to the much larger suborder Sessiliflorae lack feathery structures and grow in club-like or radiating forms. The latter suborder includes what are commonly known as sea pansies.

The earliest accepted fossils are known from the Cambrian-aged Burgess Shale (Thaumaptilon). Similar fossils from the Ediacaran (ala Charnia) may show the dawn of sea pens. Precisely what these early fossils are, however, is not decided.

Taxonomy

The order Pennatulacea consists of the following families:[2]

- Suborder Sessiliflorae

- Suborder Subsessiliflorae

-

Renilla sp. (Renillidae)

-

Veretillum sp. (Veretillidae)

-

Virgularia sp. (Virgulariidae)

Biology

As octocorals, sea pens are colonial animals with multiple polyps (which look somewhat like miniature sea anemones), each with eight tentacles. Unlike other octocorals, however, a sea pen's polyps are specialized to specific functions: a single polyp develops into a rigid, erect stalk (the rachis) and loses its tentacles, forming a bulbous "root" or peduncle at its base.[3] The other polyps branch out from this central stalk, forming water intake structures (siphonozooids), feeding structures (autozooids) with nematocysts, and reproductive structures. The entire colony is fortified by calcium carbonate in the form of spicules and a central axial rod.

Using their root-like peduncles to anchor themselves in sandy or muddy substrate, the exposed portion of sea pens may rise up to 2 metres (6.6 ft) in some species, such as the tall sea pen (Funiculina quadrangularis). Sea pens are sometimes brightly coloured; the orange sea pen (Ptilosarcus gurneyi) is a notable example. Rarely found above depths of 10 metres (33 ft), sea pens prefer deeper waters where turbulence is less likely to uproot them. Some species may inhabit depths of 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) or more.

While generally sessile animals, sea pens are able to relocate and re-anchor themselves if need be.[3] They position themselves favourably in the path of currents, ensuring a steady flow of plankton, the sea pens' chief source of food. Their primary predators are nudibranchs and sea stars, some of which feed exclusively on sea pens. When touched, some sea pens emit a bright greenish light; this is known as bioluminescence. They may also force water out of their bodies for defence, rapidly deflating and retreating into their peduncle.

Like other anthozoans, sea pens reproduce by co-ordinating a release of sperm and eggs into the water column; this may occur seasonally or throughout the year. Fertilized eggs develop into larvae called planulae which drift freely for about a week before settling on the substrate. Mature sea pens provide shelter for other animals, such as juvenile fish. Analysis of rachis growth rings indicates sea pens may live for 100 years or more, if the rings are indeed annual in nature.

Some sea pens exhibit glide reflection symmetry,[4] rare among non-extinct animals.

Aquarium trade

Sea pens are sometimes sold in the aquarium trade. However, they are generally hard to care for because they need a very deep substrate and have special food requirements.

References

- ^ a b Williams, Gary C. (2011-07-29). Thrush, Simon (ed.). "The Global Diversity of Sea Pens (Cnidaria: Octocorallia: Pennatulacea)". PLoS ONE. 6 (7): e22747. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...622747W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022747. PMC 3146507. PMID 21829500.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Pennatulacea". World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 2018-04-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 168–169. ISBN 0-03-056747-5.

- ^ Zubi, Teresa (2016-01-02). "Octocorals (Stoloniferans, soft corals, sea fans, gorgonians, sea pens) - Starfish Photos - Achtstrahlige Korallen (Röhrenkorallen, Weichkorallen, Hornkoralllen, Seefedern, Fächerkorallen)". starfish.ch. Retrieved 2016-09-08.