John Edgar Wideman

John Edgar Wideman | |

|---|---|

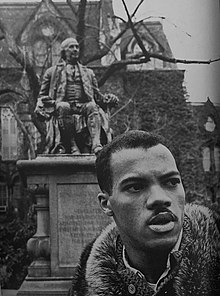

Wideman at the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards in 2010 | |

| Born | June 14, 1941 Washington, D.C., United States |

| Occupation | Author, Professor (emeritus) |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | |

| Notable works |

|

| Notable awards | |

| Spouse |

|

| Children | 3 |

John Edgar Wideman (born June 14, 1941) is an American author of novels, memoirs, short stories, essays, and other works. Among the most critically acclaimed American writers of his generation, he was the first person to win the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction twice. His writing is known for experimental techniques and a focus on the African-American experience.

Raised in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Wideman excelled as a student athlete at the University of Pennsylvania. In 1963, he became the second African American to win a Rhodes Scholarship to attend the University of Oxford. In addition to his work as a writer, Wideman has had a career in academia as a literature and creative writing professor at both public and Ivy League universities.

In his writing, Wideman has explored the complexities of storytelling, family, race, trauma, and justice in the United States. His personal experience, including the incarceration of his brother, has played a significant role in his work.

Currently, he is a professor emeritus at Brown University and lives in New York City and France.[1]

Early life and education

Wideman was born on June 14, 1941, in Washington, D.C., the oldest of five children of Edgar (1918–2001) and Bette (née French; 1921–2008) Wideman.[2][3][4]

Wideman traces his roots to the period of American slavery. On his mother's side, his great-great-great-grandmother was a slave from Maryland who had children with her master's son. Together, they relocated to an area outside of Pittsburgh either during or immediately after the American Civil War. According to Wideman family lore, this ancestor first settled the area that eventually became the Pittsburgh neighborhood of Homewood, despite the fact that a white lawyer and politician, William Wilkins, is credited with founding the community.[5] On Wideman's father's side, his ancestors have been traced to rural South Carolina, where records indicate there were both white and African-American Widemans, including one who owned slaves.[6] Wideman's paternal grandfather moved to Pittsburgh as part of the Great Migration of the early 20th century, when many African Americans fled inhospitable conditions in Southern states.[7]

Wideman's father, Edgar, graduated high school in Pittsburgh, where he was an avid basketball player. After marrying Wideman's mother, Bette, he moved with her to Washington, D.C., for a job in the U.S. Government Printing Office. The couple moved back to Pittsburgh and the Homewood neighborhood after Wideman was born in 1941. During World War II, Wideman's father enlisted in the U.S. Army and was stationed in Charleston, South Carolina, and on Saipan. After the War, he had difficulty securing employment commensurate with his skills, and worked several jobs simultaneously, including as a waiter and sanitation worker, in order to support the family. As a result, the family was able to move to a predominantly white neighborhood, Shadyside, allowing Wideman to attend Pittsburgh's Peabody High School.[8]

Wideman's teachers had noted his intelligence from an early age, and he proved to be an outstanding student. In high school, he was a star basketball player, president of the student body, and valedictorian of his class.[9] Despite his popularity, however, Wideman was socially cautious, especially around white students. Interviewed for an article in 1963, one of his white classmates recalled Wideman telling her that "he wouldn't want to be seen on the street alone with a white girl" and that "when class breaks came, he would seldom walk to the next class with the white students".[10]

Collegiate career

Wideman attended the University of Pennsylvania, where he was offered a Benjamin Franklin Scholarship for academic merit and was one of a small number of African Americans to enroll in 1959.[9][α] In his memoir, Brothers and Keepers, he described a heated freshman-year encounter with a white student in the dorm room of an African-American friend: the white student claimed to know more about blues music than Wideman did, and his friend refused to offer support. According to Wideman, the encounter left him feeling that he had "no place to hide",[13] and he was in an environment "that continually set me against them and against myself".[14] Feeling alienated, he decided to quit college, but was stopped by his basketball coach at a bus station, where Wideman was about to board a bus back to Pittsburgh.[15] Despite his trepidation about college, Wideman persevered. Addressing his brother in Brothers and Keepers, he summarized his motivation:

I was running away from Pittsburgh, from poverty, from blackness. To get ahead, to make something of myself, college had seemed a logical, necessary step; my exile, my flight from home began with good grades, with good English, with setting myself apart long before I'd earned a scholarship and a train ticket over the mountains to Philadelphia…if I ever had any hesitations or reconsiderations about the path I'd chosen, youall were back home in the ghetto to remind me how lucky I was.[16]

Once again, Wideman excelled both academically and in athletics, becoming a star basketball player. By his senior year, he was captain of the basketball team, which he led in scoring, and was named to the "All Ivy League" team.[17] While his team lost the Ivy League championship to Princeton University his senior year, they won the "Big 5" tournament, which has traditionally determined the best college basketball team in Philadelphia, pitting Penn against Villanova, Saint Joseph's, La Salle, and Temple universities.[18] For his academic achievements, which included winning campus-wide awards for both creative and scholarly writing, Wideman was inducted into the Phi Beta Kappa national honor society.[19]

In 1963, before graduating with a bachelor's degree in English, Wideman was named a Rhodes Scholar, becoming just the second African American to win the prestigious award from the University of Oxford.[20][β] The achievement brought him national attention: he was profiled in LOOK Magazine that spring, in an article entitled, "The Astonishing John Wideman". The article described Wideman as having been "showered with so many academic and athletic honors, awards and 'firsts' that he is unable to enumerate them. He sometimes forgets that he won a prize that another student would consider the high point of a college career".[21]

In the fall of 1963, Wideman moved to England to begin his studies at Oxford, where he pursued a thesis on 18th-century British fiction.[20] He also continued to play basketball via the Oxford University Basketball Club, where one of his teammates was fellow Rhodes Scholar, and future NBA All-Star and United States Senator, Bill Bradley. The two had played against each other as undergraduates, when Bradley was at Princeton. At Oxford, their team won an intercollegiate championship.[22]

In 1965, Wideman married Judith Goldman, a white Jewish woman from Long Island whom he began dating when both were undergraduates at Penn. The following year, Wideman received a BPhil degree from Oxford and returned to the U.S. He spent the 1966–67 academic year at the Iowa Writers Workshop, where he studied under Kurt Vonnegut and José Donoso.[22]

Writing and teaching career

Philadelphia and early novels

After leaving the University of Iowa in 1967, Wideman accepted a faculty position at his alma mater, the University of Pennsylvania.[23] That summer, his first novel, A Glance Away, was published. Wideman's editor, Hiram Haydn, had seen his profile in LOOK Magazine and contacted Wideman before he left for Oxford, asking the aspiring author to send him his writing. While Wideman was at Oxford, Haydn read the unfinished manuscript of A Glance Away and agreed to publish it.[24] The novel garnered positive reviews. A reviewer in The New York Times Book Review described Wideman as "a novelist of high seriousness and depth" who had written "a powerfully inventive" debut.[25] Despite a positive critical reception, however, the novel did not attract a large audience.

Responding to student demand, Wideman offered Penn's first classes in African-American literature in 1968. In the same year, his first son, Daniel, was born.[23] Wideman also became an assistant coach for the varsity men's basketball team that he had played for as a student.[26]

In 1970, Wideman's second son, Jacob, was born.[23] In the same year, his second novel, Hurry Home, was published. A reviewer for The New York Times admired the novel's "dazzling display" of "Joycean" prose and Wideman's "formidable command of the techniques of fiction".[27]

Wideman's initial courses in African-American literature eventually grew into a program in African American Studies, which Wideman helped to establish. From 1971 to 1973, he served as director of the program.[23] In 1972, he stepped down as an assistant basketball coach.

In 1973, Wideman's third novel, The Lynchers, was published. Examining violent strains of black nationalist ideology that had emerged during the 1960s, the novel depicts African-American characters who plan to lynch a white police officer. Writing in The New York Times, Anatole Broyard claimed that Wideman "can make an ordinary scene sing the blues like nobody's business", although he found the novel to be flawed.[28] Despite its provocative subject matter, it experienced only modest sales.

In 1974, Wideman was promoted to a full professorship of English at Penn, and he received a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to pursue research in African-American literature.[29] However, he had already begun to look for a reprieve from his duties at the institution, as well as life in Philadelphia, in order to focus more on his writing and raising a family. Having previously visited the University of Wyoming, he accepted an offer to join its faculty.[23]

Wyoming, family tragedy, literary success

Wideman joined the faculty of the University of Wyoming in 1975. That same year, Wideman's daughter, Jamila, was born. The circumstances of her birth were traumatic, as a complication caused Wideman's wife, Judith, to be transported by ambulance from Laramie, Wyoming, to Denver, Colorado, where Jamila was born two months premature.[30]

After Jamila and Judith recovered, the family returned to Laramie, where Wideman learned that his youngest brother, Robert, was a fugitive. Ten years younger than Wideman, Robert had grown up in Homewood, where Wideman's parents had returned for financial reasons.[31] During the 1960s and early 1970s, the neighborhood was in a state of decline—it has frequently been described as a ghetto. Robert began to use drugs, a habit which he supported via petty crime. In November 1975, along with two accomplices, he participated in a robbery scheme that went awry when the intended victim, a fence named Nicola Morena, fled. One of Robert's accomplices shot Morena as he ran. A short time later, a passerby encountered the wounded man and called for an ambulance. Morena was taken to the nearest hospital, which did not have the surgeon necessary to treat his wound, and after a period of waiting, he was transported to another hospital, where he died. The victim's family later filed a lawsuit against the city of Pittsburgh, the hospitals and doctors involved, and the ambulance drivers, claiming negligence. That suit was not successful, although the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania acknowledged that a delay in Morena's treatment was "a contributing factor in causing his death".[32] The family ultimately settled a malpractice lawsuit against the hospital system.[33]

Robert and his accomplices fled Pittsburgh and arrived in Laramie, where Wideman let them spend a night in his house, an act he has attributed to naïveté. Robert and his accomplices then drove to Colorado, where they were apprehended. Afterward, police in Wyoming accused Wideman of aiding a fugitive, but no charges were filed.[34]

According to Pennsylvania law, because the attempted armed robbery of Morena resulted in a homicide, the charge against the shooter was second-degree murder, and because Robert was an accomplice, he faced the same charge as the shooter. At trial, Robert was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. All of his appeals failed.[35][33]

Wideman incorporated his brother's experience into his subsequent work. After an eight-year publication hiatus, he published two books simultaneously: a story collection, Damballah, and a novel, Hiding Place, both of which appeared in 1981 and allude to the events that resulted in the imprisonment of Wideman's brother. He followed these books with another novel, Sent for You Yesterday, in 1983. Because these three books share characters and a setting in the Pittsburgh neighborhood of Homewood, they are frequently referred to as the "Homewood trilogy".

The trilogy was celebrated upon publication, inspiring a claim in The New York Times that Wideman was "one of America's premier writers of fiction."[36] For many critics and scholars, the trilogy represents Wideman's artistic breakthrough, with some even considering it his greatest literary achievement.[37] Surveying Wideman's career in The Nation in 2016, the critic Jesse McCarthy claimed that the trilogy shows Wideman "achieving a distinctive voice that is more confident and vernacular than in his early work".[38] Some of the stories in Damballah, in particular, including the title story, which depicts a slave refusing to alter his behavior in the face of cruelty by his masters, have been widely anthologized.

In 1984, Wideman followed the successful Homewood trilogy with what has been called his most popular book, Brothers and Keepers.[38] Wideman's first memoir delves into his brother Robert's story. Stylistically, the book is distinctive for its use of multiple voices, alternating between Wideman and his brother. It is also notable for its exploration of the realities of the American criminal justice system and life in prison, particularly for African Americans. Ishmael Reed, reviewing the book in The New York Times, called it "a rare triumph".[39] It has since become a staple of college courses across the U.S.

Massachusetts, second family tragedy, prolific period

In 1986, Wideman joined the faculty of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, where the prominent author James Baldwin was a visiting member of the faculty.[40] Wideman taught in the MFA Program for Poets and Writers.

In the same year, Wideman's son, Jacob, who was sixteen years old, stabbed a fellow camper to death during a youth camping trip in Arizona. He then fled the state. At his parents' urging, he surrendered to law enforcement, and after being released into parental custody, underwent psychiatric evaluation in Massachusetts. During his stay in a psychiatric facility, he called police in Arizona and confessed his guilt. However, before a judge, he pleaded not guilty, and his case was scheduled for trial.[41] A plea bargain was then struck, in which Jacob pleaded guilty to first-degree murder and was sentenced to life in prison, with a possibility of parole after 25 years.[42]

Once again, Wideman turned to writing, entering what is, to date, the most prolific period of his career. A novel written before his son Jacob's crime, entitled Reuben, appeared in 1987. This was followed by a collection of stories, entitled Fever, in 1989. The following year saw the publication of the novel Philadelphia Fire, which garnered both critical acclaim and literary awards. Inspired by the 1985 police bombing of the Philadelphia headquarters of the black liberation group known as MOVE—an act that resulted in the death of five children and the loss of two city blocks[43]—the "intense, poetic narrative"[44] centers on one man's attempt to find, and write about, a child rumored to have survived the tragedy.

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Philadelphia Fire was followed by a story collection, The Stories of John Edgar Wideman (later re-issued as All Stories Are True) in 1992; a memoir, Fatheralong: A Meditation on Fathers and Sons, Race and Society, in 1994, and two more novels, The Cattle Killing in 1996 and Two Cities in 1998. Notably, while Wideman wrote about his son's story in some of these books (for example, in Philadelphia Fire[45] and in Fatheralong[46]) he has not written a memoir about it, nor has he written fiction explicitly inspired by it. In interviews, he has frequently declined to discuss the case.[47]

During this period, Wideman was in demand as "one of America's most distinguished writers".[48] He was asked to edit anthologies, provide introductions for books, and appear in various media, including television, to comment on societal issues, particularly those affecting African Americans. Additionally, his daughter, Jamila, became a star basketball player and, in 1997, the third overall pick in the inaugural draft of the Women's National Basketball Association,[49] bringing further media attention, including a cover story in Sports Illustrated magazine.

In 2000, Wideman and his wife, Judith, divorced.[50]

In 2001, the University of Massachusetts appointed Wideman a Distinguished Professor;[51] it was the same year that another memoir, Hoop Roots, appeared, focusing on Wideman's experience as a player and fan of basketball. A review in Bookpage hailed it as "one of the best books ever written about the sport".[52] It was followed by a nonfiction book on Martinique entitled The Island: Martinique (2003).

Brown and latest work

In 2004, Wideman was appointed Asa Messer Professor and Professor of Africana Studies and Literary Arts at Brown University.[53] In the same year, he married French journalist Catherine Nedonchelle.[54]

The following year, his story collection, God's Gym, was published. This was followed by his first novel in a decade, and tenth overall, Fanon, which appeared in 2008. In 2010, a collection of flash fiction, entitled Briefs, was published, inspiring a theatrical adaptation that premiered in Los Angeles in 2018.[55]

In 2014, after a decade at Brown University, and nearly 50 years teaching in academia, Wideman became an emeritus professor.[37] He has since published a hybrid work of fiction and nonfiction that explores the life of the father of Emmet Till, entitled Writing to Save a Life: The Louis Till File (2016). He published a collection of stories, American Histories, in 2018.

Family

Wideman was married to Judith Ann Goldman, an attorney, from 1965 until their divorce in 2000. The couple had three children together: Daniel Wideman is a poet, playwright, and essayist, as well as a business executive;[56][57] Jacob Wideman was convicted of a murder committed while he was a minor and sentenced to life in prison in Arizona,[58] and Jamila Wideman is a lawyer and executive at the National Basketball Association, having played professional basketball in the Women's National Basketball Association and the Israeli League.[59][60]

In 2004, Wideman married French journalist Catherine Nedonchelle. He resides in France and on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in New York City.

Wideman's brother, Robert, was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole for his role in a 1975 murder. After more than 40 years in prison, his sentence was commuted and he was released on July 2, 2019.[61]

Honors

Athletic honors

- Philadelphia Big 5 Hall of Fame, inducted 1974[62]

- University of Pennsylvania Athletics Hall of Fame, inducted 1998[63]

Honors for body of work

In 1993, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, in awarding him a fellowship, noted that Wideman "has contributed to a new humanist perspective in American literature, distilling personality and history, crime and mysticism, art and the exigencies of material life into his work."[64] Honors bestowed for his entire body of work include:

- Honorary Doctorate, University of Pennsylvania (1986)[65]

- John Dos Passos Prize for Literature (1986)[66]

- Lannan Literary Award in Fiction (1991)[67]

- Honorary Doctorate, Rutgers University (1991)[68]

- American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Elected Member (1992)[69]

- St. Botolph Club Foundation Distinguished Artist Award (1992)[70]

- MacArthur Foundation Fellowship (1993)[64]

- Lila Wallace-Reader’s Digest Writers’ Award (1998)[71]

- Rea Award for the Short Story (1998)[72]

- Honorary Doctorate, Colby College (1998)[73]

- Honorary Doctorate, University of Bern (1998)[74]

- Honorary Doctorate, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York (1999)[75]

- New England Book Award for Literary Excellence (2001)[76]

- Honorary Doctorate, Columbia College Chicago (2003)[77]

- Langston Hughes Medal (2004)[78]

- Katherine Anne Porter Award (2008)[79]

- Honorary Doctorate, State University of New York at New Paltz (2010)[80]

- Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards Lifetime Achievement Award (2011)[81]

- American Academy of Arts and Letters, Elected Member (2016)[82]

- Honorary Doctorate, Duquesne University (2017)[83]

- Lannan Literary Award for Lifetime Achievement (2018)[84]

- Stephen E. Henderson Award for Outstanding Achievement (2019)[85]

- PEN/Malamud Award for Excellence in the Short Story (2019)[86]

Honors for individual works

- American Library Association Notable Books List for Sent for You Yesterday (1984)[87]

- PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction for Sent for You Yesterday (1984)[88]

- American Library Association Notable Books List for Brothers and Keepers (1985)[89]

- National Magazine Award for "Doc’s Story", originally published in Esquire (1987)[90]

- PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction for Philadelphia Fire (1991)[88]

- American Book Award for Philadelphia Fire (1991)[91]

- James Fenimore Cooper Prize for Best Historical Fiction for The Cattle Killing (1997)[92]

- O. Henry Award for "Weight", originally published in Callaloo (2000)[93]

- O. Henry Award for "Microstories", originally published in Harper's Magazine (2010)[94]

- Prix Femina Étranger for Writing to Save a Life: The Louis Till File (2017)[95]

- PEN Oakland/Josephine Miles Literary Award for Writing to Save a Life: The Louis Till File (2017)[96]

- O. Henry Award for "Maps and Ledgers", originally published in Harper's Magazine (2019)[97]

Wideman's winning the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction in 1991 marked the first time a writer had won that prize twice, a feat that has since been accomplished by three other writers: Philip Roth, E. L. Doctorow, and Ha Jin.[88]

In addition, Wideman's memoir, Brothers and Keepers, and his book, Writing to Save a Life, were both finalists for the National Book Critics Circle Award.[98] His memoir, Fatheralong, was a finalist for the National Book Award.[99]

Wideman's short works have been widely anthologized, including in the Norton Anthology of African American Literature,[100] the Oxford Book of American Short Stories,[101] and The Heath Anthology of American Literature,[102] among others.

Wideman has been a visiting fellow, professor, or speaker at numerous institutions. His work has been translated into many languages and continues to be the focus of academic study. In that regard, the John Edgar Wideman Society was formed to promote scholarship and awareness of Wideman's work. Affiliated with the American Literature Association, it held its first international conference in 2003.[103] Wideman's papers, including manuscripts, correspondence, and other materials, are housed at the Houghton Library at Harvard University.[104]

Work

Style

Wideman's writing is known for its complexity, with critics describing it as cerebral and experimental.[47] It is also known for combining literary diction with what has been called African-American Vernacular English. In some works, Wideman's writing relies on sentence fragments, whereas elsewhere, he has written a single sentence that spans several pages. He has sometimes used the stream-of-consciousness technique and sudden, unannounced shifts in perspective. In much of his writing, Wideman eschews punctuation such as question marks or quotation marks, relying instead on context to identify speakers or discern questions from statements.[37] In some cases, Wideman mixes nonfiction and fiction in the same work.

Among scholars, there is discussion as to whether Wideman is properly assessed as a modernist—because of his use of literary style to convey meaning—or as a postmodernist—because of a narrative self-awareness that calls attention to authorship in his work.[105][106] The scholar D. Quentin Miller, however, argues that Wideman's works "resist categorization".[37]

Themes

While Wideman's work is thematically diverse, some common themes emerge. Most prominently, Wideman is known for his exploration of race, a subject that factors in all of his books. His fiction depicts African-American characters dealing with the challenges and alienation of life in a predominantly white society. His work also depicts the ways that race and racism are constructed by, and manifested in, society—from language to interpersonal relationships to interactions with the state.[107]

Another chief concern of Wideman's writing is family, particularly as the key unit of community and cultural survival. Yet family, for Wideman, is inherently contentious: his writing investigates the ways that family is necessary for protection and individual development, while at the same time proving to be something one needs to be protected from in order to find one's true self.[108] This exploration is explicit in Brothers and Keepers, in which Wideman and his brother navigate the complexities of their familial relationship.

Another of Wideman's frequent themes is storytelling. Of particular importance is the notion that "all stories are true", which Wideman has used in multiple works, including as the title for one of his story collections. The scholar Heather Russell explains that, in focusing on this concept, Wideman's writing "reflects African American traditions of storytelling within which myth, history, parable, parody, folklore, fact, and fiction exist in synergy. Storytelling functions as a bridge between both past, present, and future and between history, memory, and the imagination".[109]

Frequently in Wideman's work, storytelling is focused on trauma—expressing it, escaping it, or healing from it. Trauma, in Wideman's work, can exist on the level of the individual and for all of society. The scholar Tracie Church Guzzio summarizes Wideman's approach to trauma when she claims that his writing "illustrates that the trauma suffered by African Americans in the period of slavery in America is re-lived and re-experienced in the continuing racism confronting African Americans in their daily lives as well as in the images projected by history, literature, and popular culture".[110]

Influences

In interviews, Wideman has typically declined to identify his influences.[37] However, scholars and critics have pointed to figures that, judging from Wideman's work and interviews, appear to be literary or intellectual influences. These include W. E. B. Du Bois (to whom Wideman has dedicated work), Frantz Fanon (inspiration for Wideman's novel, Fanon), Ralph Ellison, James Baldwin, and, especially in his early work, the modernist writers James Joyce, T.S. Eliot, and William Faulkner.

Selected bibliography

Novels

- A Glance Away (Harcourt, 1967; re-release by Allison & Busby, 1984) ISBN 978-0557314775

- Hurry Home (Harcourt, 1970) ISBN 978-0557314829

- The Lynchers (Harcourt, 1973) ISBN 978-0557314836

- Hiding Place (Avon, 1981; Allison & Busby, 1984) ISBN 978-0395897980

- Sent for You Yesterday (Avon, 1983; Allison & Busby, 1984) ISBN 978-0395877296

- Reuben (Henry Holt, 1987) ISBN 978-2070732340

- Philadelphia Fire (Henry Holt, 1990) ISBN 978-0618509645

- The Cattle Killing (Houghton Mifflin, 1996) ISBN 978-0395877500

- Two Cities (Houghton Mifflin, 1998) ISBN 978-0618001859

- Fanon (Houghton Mifflin, 2008) ISBN 978-0547086163

Omnibus editions

- The Homewood Books (includes Damballah, Hiding Place and Sent for You Yesterday; University of Pittsburgh Press, 1992; as The Homewood Trilogy, Avon, 1985) ISBN 978-0822938316

- A Glance Away, Hurry Home, and The Lynchers: Three Early Novels by John Edgar Wideman (Henry Holt, 1994)

Story collections

- Damballah (short stories; Avon, 1981; Allison & Busby, 1984) ISBN 978-0395897973

- Fever (short stories; Henry Holt, 1989)

- The Stories of John Edgar Wideman (Pantheon Books, 1992; published as All Stories Are True, Vintage Books, 1993) ISBN 978-0679407195

- God's Gym (short stories; Houghton Mifflin, 2005) ISBN 978-0618711994

- Briefs (micro stories; Lulu Press, 2010) ISBN 978-0557310043

- American Histories (Scribner, 2018) ISBN 978-1501178351

Memoirs and other

- Brothers and Keepers (memoir; Henry Holt, 1984; Allison & Busby, 1985) ISBN 978-0618509638

- Fatheralong: A Meditation on Fathers and Sons, Race and Society (Pantheon, 1994)

- Hoop Roots: Basketball, Race, and Love (memoir; Houghton Mifflin, 2001)

- (Editor) My Soul Has Grown Deep: Classics of Early African-American Literature (Running Press, 2001)

- (Editor) 20: The Best of the Drue Heinz Literature Prize (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2001)

- The Island: Martinique (National Geographic Directions, 2003)

- Writing to Save a Life: The Louis Till File (Scribner, 2016) ISBN 978-1501147296

Further reading

- Auger, Philip, Native Sons in No Man's Land: Rewriting Afro-American Manhood in the Novels of Baldwin, Walker, Wideman, and Gaines, New York: Garland Publishing, 2000.

- Byerman, Keith E., The Life and Work of John Edgar Wideman, Santa Barbara: Praeger Books, 2013.

- Church Guzzio, Tracie, All Stories are True: History, Myth, and Trauma in the Work of John Edgar Wideman, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2011.

- Coleman, James W., Blackness and Modernism: The Literary Career of John Edgar Wideman, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1989.

- Coleman, James W., Writing Blackness: John Edgar Wideman's Art and Experimentation, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2010.

- D'Amore, Jonathan, American Authorship and Autobiographical Narrative: Mailer, Wideman, Eggers, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

- Dubey, Madhu, Signs and Cities: Black Literary Postmodernism, Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- Eschborn, Ulrich, Stories of Survival: John Edgar Wideman's Representations of History, WVT Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, Trier, 2011.

- Eschborn, Ulrich, "'To Democratize the Elements of the Historical Record': An Interview with John Edgar Wideman About History in His Work", Callaloo, Volume 33, Number 4, 2010, The Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 982–998.

- Feith, Michel, John Edgar Wideman and Modernity: A Critical Dialogue, Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2019.

- Mbalia, Doreatha Drummond, John Edgar Wideman: Reclaiming the African Personality, Selinsgrove: Susquehanna University Press; and London: Associated University Presses, 1995.

- Miller, D. Quentin, Understanding John Edgar Wideman, Columbia: The University of South Carolina Press, 2018.

- Murray, Rolland, Our Living Manhood: Literature, Black Power, and Masculine Ideology, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

- Rowell, Charles Henry (editor), Callaloo Special Issue: John Edgar Wideman: The European Response, Volume 22, Number 3, Summer 1999, The Johns Hopkins University Press. E-ISSN 1080-6512. Print ISSN 0161-2492 doi:10.1353/cal.1999.0130

- TuSmith, Bonnie (editor), Conversations with John Edgar Wideman, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1998.

- TuSmith, Bonnie, and Keith E. Byerman (editors), Critical Essays on John Edgar Wideman, Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2006.

Notes

- ^ Byerman claims 10 African Americans enrolled at Penn in 1959,[9] a number Wideman uses in his memoir, Brothers and Keepers.[11] A website published by Penn's University Archives and Records Center claims there were only six African-American enrollees in 1959, out of a class of more than 1,700.[12]

- ^ Wideman shared this distinction with another African-American student, J. Stanley Sanders of the University of Southern California, who was also named a Rhodes Scholar in 1963.[20]

References

- ^ "John Edgar Wideman". Simon & Schuster. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ Byerman, Keith (2013). The Life and Work of John Edgar Wideman. Santa Barbara: Praeger. p. 2. ISBN 9780313366338. OCLC 867141160.

- ^ "Veterans Affairs record: Edgar Wideman". Fold3. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ^ "Bette A. Wideman obituary". legacy.com.

- ^ Byerman, Keith. The Life and Work of John Edgar Wideman. p. 1.

- ^ Byerman, Keith. The Life and Work of John Edgar Wideman. p. 2.

- ^ Byerman, Keith. The Life and Work of John Edgar Wideman. p. 3.

- ^ Byerman, Keith. The Life and Work of John Edgar Wideman. p. 4.

- ^ a b c Byerman, Keith. The Life and Work of John Edgar Wideman. p. 5.

- ^ Shalit, Gene (May 21, 1963). "The Astonishing John Wideman". LOOK Magazine. 27 (10): 36.

- ^ Wideman, John Edgar. Brothers and Keepers. p. 29.

- ^ "1963 City Champions". University Archives and Records Center, University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ Wideman, John Edgar (2005). Brothers and Keepers. New York: Mariner Books. p. 30. ISBN 978-0618509638.

- ^ Wideman, John Edgar. Brothers and Keepers. p. 31.

- ^ "Wideman on Campus". writing.upenn.edu. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ Wideman, John Edgar. Brothers and Keepers. p. 27.

- ^ Byerman, Keith. The Life and Work of John Edgar Wideman. p. 6.

- ^ "1963 City Champions". University Archives and Records Center, University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Ivy League Ideal". University Archives and Records Center, University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ a b c Byerman, Keith. The Life and Work of John Edgar Wideman. p. 7.

- ^ Shalit, Gene (May 21, 1963). "The Astonishing John Wideman". LOOK Magazine. 27 (10): 33.

- ^ a b Byerman, Keith. The Life and Work of John Edgar Wideman. p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e Byerman, Keith. The Life and Work of John Edgar Wideman. p. 9.

- ^ "INTERVIEW: John Edgar Wideman - The Art of Fiction No. 171 > Paris Review". NEO•GRIOT. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Junkie's Homecoming". movies2.nytimes.com. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "John Edgar Wideman". sites.psu.edu. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Cecil Could Run -- But He Couldn't Hide". movies2.nytimes.com. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "A Lynching in Black Face". movies2.nytimes.com. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "John Wideman NEH Grant". securegrants.neh.gov. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ Wideman, John Edgar. Brothers and Keepers. p. 16.

- ^ Byerman, Keith. The Life and Work of John Edgar Wideman. p. 17.

- ^ "Morena v. South Hills Health System". Justia Law. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ a b "Pa. pardons board votes 5-0 to grant clemency to Robert Wideman in 1975 murder". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- ^ Wideman, John Edgar. Brothers and Keepers. p. 14.

- ^ Byerman, Keith. The Life and Work of John Edgar Wideman. p. 18.

- ^ Books, Featured Author: John Edgar Wideman, The New York Times, on the Web (accessed October 17, 2011).

- ^ a b c d e Miller, D. Quentin (2018). Understanding John Edgar Wideman. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 9781611178241. OCLC 985079951.

- ^ a b McCarthy, Jesse (November 29, 2016). "Wideman's Ghosts". ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Of One Blood, Two Men". movies2.nytimes.com. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "BALDWIN TEACHES". UPI. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Children of promise, children of pain: The Jacob Wideman case". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Writer's son given life term in death of New York youth". The New York Times. October 16, 1988. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Why Have So Many People Never Heard Of The MOVE Bombing?". NPR.org. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ PHILADELPHIA FIRE by John Edgar Wideman | Kirkus Reviews.

- ^ Wideman, John Edgar (1990). Philadelphia Fire. New York: Henry Holt and Company. pp. 97–151.

- ^ Wideman, John Edgar (1994). Fatheralong: A Meditation on Fathers and Sons, Race and Society. New York: Pantheon Books. pp. 177–197.

- ^ a b Williams, Thomas Chatterton (January 26, 2017). "John Edgar Wideman Against the World". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Jamila Wideman has had to confront a dark family legacy". si.com. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Trojans Drafted 1-2; Sparks Take Wideman". Los Angeles Times. April 29, 1997. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ Byerman, Keith. The Life and Work of John Edgar Wideman. pp. vii.

- ^ "John Edgar Wideman Appointed Distinguished Professor". umass.edu. University of Massachusetts. February 7, 2001. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ "Hoop Roots by John Edgar Wideman - Review | BookPage". BookPage.com. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Eighteen Brown Faculty Members Appointed to Named Professorships". brown.edu. Brown University. November 10, 2004. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ "John Edgar Wideman, his words "Do Apply"". African American Registry. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ Theatre, Word. "Witness: The John Edgar Wideman Experience". WordTheatre | Giving Voice to Great Writing. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Artists: Daniel Wideman". www.calabashfestival.org. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ "Daniel Wideman". Medium. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ Kiefer, Michael (January 2, 2019). "Released Arizona Killer Jacob Wideman Appeals Reimprisonment". azcentral.com. Arizona Republic. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ Lee, Laura (August 12, 2001). "Perspective; Changing Courts: Brother's Incarceration Shapes Player's Goals". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- ^ "Former WNBA Player Jamila Wideman Joins NBA's Player Development Department". hoopfeed.com. September 6, 2018. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ Navratil, Liz (July 2, 2019). "Gov. Wolf commutes sentence for Allegheny County man convicted in 1975 murder". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ "Philadelphia Big 5 | Hall of Fame". philadelphiabig5.org. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Penn Athletics Hall of Fame". University of Pennsylvania Athletics. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ a b "John Edgar Wideman MacArthur Fellowship Citation". macfound.org. John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ "Honorary Degree Recipients | Penn Secretary". secretary.upenn.edu. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Dos Passos Prize Past Recipients and Select Works". www.longwood.edu. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "John Edgar Wideman". Lannan Foundation. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Past Rutgers University Honorary Degree Recipients | Page 11 | Office of the Secretary of the University". universitysecretary.rutgers.edu. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Member Directory", American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

- ^ sbcfadmin. "Distinguished Artist Award – St. Botolph Club Foundation". Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Lila Wallace-Readers Digest Writers' Award" (PDF). wallacefoundation.org.

- ^ "Rea Award for the Short Story: John Edgar Wideman". reaaward.org. Dungannon Foundation. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ "UMass Amherst English Professor John Edgar Wideman Awarded Honorary Degree by Colby College". Office of News & Media Relations | UMass Amherst. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ Universitat Bern (2017). "List of Honorary Promotions" (PDF). www.unibe.ch. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "John Jay College Faculty Senate Minutes April 1999" (PDF). www.lib.jjay.cuny.edu.

- ^ "New England Book Awards – NEIBA". Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Honorary Degree Recipients - College Archives". library.colum.edu.

- ^ Admin, Website (July 4, 2015). "Medallion Recipients | The City College of New York". www.ccny.cuny.edu. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ^ "Awards – American Academy of Arts and Letters". Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ^ SysAdmin. "Distinguished Speaker Series: John Edgar Wideman – SUNY New Paltz News". Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "76th Annual Anisfield-Wolf Book Prize Winners Announced", August 11, 2011.

- ^ "2016 Newly Elected Members", American Academy of Arts and Letters.

- ^ "Bill Strickland, John Edgar Wideman to Receive Duquesne Honorary Degrees". www.duq.edu. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "John Edgar Wideman Lannan Literary Award". lannan.org. Lannan Foundation. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ Pierrot, Gregory (March 31, 2019). "2019 AALCS AWARDS RECIPIENTS". African American Literature and Culture Society. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Announcing the 2019 PEN/Malamud Award Winner!". The PEN/Faulkner Foundation. Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- ^ "ALA Notable Books List 1983" (PDF). American Library Association. 1984. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c "Past Winners and Finalists | The PEN/Faulkner Foundation". Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "ALA Notable Books List 1984" (PDF). American Library Association. 1985. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "National Magazine Award Winners 1966-2015". asme.magazine.org. American Society of Magazine Editors. Archived from the original on March 26, 2019. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ "American Book Awards Previous Winners" (PDF). beforecolumbusfoundation.com.

- ^ "Society of American Historians Prize for Historical Fiction (formerly known as the James Fenimore Cooper Prize) | Society of American Historians". sah.columbia.edu. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "English Professor John Edgar Wideman of UMass Amherst Receives O. Henry Award for Best Short Story". umass.edu. University of Massachusetts. October 6, 2000. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ "PEN/O. Henry Prize Stories 2010 | PenguinRandomHouse.com: Books". PenguinRandomhouse.com. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ "John Edgar Wideman – Canongate Books". canongate.co.uk. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Awards & Award Winners". PEN Oakland. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- ^ "Announcing the 100th Annual O. Henry Prize". Literary Hub. May 16, 2019. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ "National Book Critics Circle: awards". bookcritics.org. Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "National Book Awards 1994". National Book Foundation. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Contents | The Norton Anthology of African American Literature | W. W. Norton & Company". books.wwnorton.com. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Table of Contents: Oxford Book of American Short Stories". library.villanova.edu.

- ^ "Heath Anthology of American Literature John Edgar Wideman - Author Page". college.cengage.com. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- ^ "Membership Information - John Edgar Wideman Literary Society". webspace.ship.edu. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "John Edgar Wideman Papers". hollis.harvard.edu. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ Ramsey, Priscilla R. (1997). "John Edgar Wideman's First Fiction: Voice and the Modernist Narrative". CLA Journal. 41 (1): 1–23. ISSN 0007-8549. JSTOR 44323037.

- ^ Wideman, John Edgar; Hoem, Sheri I. (2000). ""Shifting Spirits": Ancestral Constructs in the Postmodern Writing of John Edgar Wideman". African American Review. 34 (2): 249–262. doi:10.2307/2901252. ISSN 1062-4783. JSTOR 2901252.

- ^ Russell, Heather (2006). "Race, Representation, and Intersubjectivity in the Works of John Edgar Wideman". In TuSmith, Bonnie; Byerman, Keith (eds.). Critical Essays on John Edgar Wideman. The University of Tennessee Press. pp. 46. ISBN 978-1572334694. OCLC 470064569.

- ^ Page, Eugene Philip (2006). ""Familiar Strangers": The Quest for Connection and Self-Knowledge in Brothers and Keepers". In TuSmith, Bonnie; Byerman, Keith (eds.). Critical Essays on John Edgar Wideman. The University of Tennessee Press. p. 4.

- ^ Russell, Heather (2006). "Race, Representation, and Intersubjectivity in the Works of John Edgar Wideman". In TuSmith, Bonnie; Byerman, Keith (eds.). Critical Essays on John Edgar Wideman. p. 51.

- ^ Guzzio, Tracie Church. (2013). All Stories Are True: History, Myth and Trauma in the Work of John Edgar Wideman. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. p. 12. ISBN 978-1617038334. OCLC 925995917.

External links

- Steven Beeber (Spring 2002). "John Edgar Wideman, The Art of Fiction No. 171". The Paris Review.

- "Salon Interview", LAURA MILLER

- "John Edgar Wideman", The New York Times

- "Featured Author: John Edgar Wideman", The New York Times

- John Edgar Wideman Literary Society

- Source: Lulu Press Release. March 2010.

- Crime Watch Daily with Chris Hansen

- 1941 births

- Living people

- 20th-century American novelists

- 21st-century American non-fiction writers

- 21st-century American novelists

- African-American academics

- African-American non-fiction writers

- African-American novelists

- African-American short story writers

- African-American studies scholars

- Alumni of New College, Oxford

- American Book Award winners

- American Rhodes Scholars

- American book editors

- American male non-fiction writers

- American male novelists

- American male short story writers

- American memoirists

- American short story writers

- Brown University faculty

- Harper's Magazine people

- Iowa Writers' Workshop alumni

- James Fenimore Cooper Prize winners

- MacArthur Fellows

- Novelists from Massachusetts

- Novelists from Pennsylvania

- Novelists from Rhode Island

- Novelists from Washington, D.C.

- O. Henry Award winners

- PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction winners

- University of Massachusetts Amherst faculty

- Writers from Pittsburgh

- Writers from Providence, Rhode Island