Máel Coluim, King of Strathclyde

| Máel Coluim | |

|---|---|

| King of Strathclyde | |

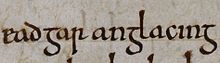

Máel Coluim's name and title as it appears on folio 5v of British Library Cotton Domitian A VIII (De primo Saxonum adventu): "Malcolm rex Cumbrorum".[1] | |

| Predecessor | Dyfnwal ab Owain or Rhydderch ap Dyfnwal |

| Successor | Owain ap Dyfnwal |

| Died | 997 |

| Issue | Owain Foel? |

| Father | Dyfnwal ab Owain |

Máel Coluim (died 997) was a tenth-century King of Strathclyde.[note 1] He was a younger son of Dyfnwal ab Owain, King of Strathclyde, and thus a member of the Cumbrian dynasty that had ruled the kingdom for generations. Máel Coluim's Gaelic name could indicate that he was born during either an era of amiable relations with the Scots, or else during a period of Scottish overlordship. In 945, the Edmund I, King of the English invaded the kingdom, and appears to have granted the Scots permission to dominate the Cumbrians. The English king is further reported to have blinded several of Máel Coluim's brothers in an act that could have been an attempt to deprive Dyfnwal of an heir.

It is unknown when Dyfnwal's reign came to an end. There is reason to suspect that a certain Rhydderch ap Dyfnwal was a son of his, and that this man ruled when he assassinated the reigning King of Alba in 971. Certainly by 973, Máel Coluim was associated with the kingship, as both he and his father are recorded to have been participated in a remarkable meeting of kings assembled by Edgar, King of the English. The context of this assembly is not entirely clear. It could have concerned the stability of the border between the English realm and that of the Scots and Cumbrians. It could have also focused upon lurking threat of Vikings based in Dublin and the Isles.

Máel Coluim's father died in 975, having set off upon a pilgrimage to Rome. Quite when Máel Coluim succeeded Dyfnwal is uncertain. It could have been before, during, or after the assembly of 973. In any case, Máel Coluim's reign was evidently unremarkable, although the tenth-century Saltair na Rann preserves several lines of verse in his praise. Máel Coluim appears to have been succeeded by a brother, Owain. This man's successor, Owain Foel, seems to have been a son of Máel Coluim.

Dyfnwal's sons and English aggression

Máel Coluim was a son of Dyfnwal ab Owain, King of Strathclyde,[9] a man who ruled the Cumbrian Kingdom of Strathclyde from about the 930s to the 970s.[10] Máel Coluim's name is Gaelic, and may be evidence of a marriage alliance between his family and the neighbouring Alpínid dynasty of the Kingdom of Alba.[11] The name may also reveal that Máel Coluim was a godson of his northern namesake, Máel Coluim mac Domnaill, King of Alba, and could perhaps be indicative of Dyfnwal's submission to this Scottish king.[12][note 2]

In 945, the "A" version of the eleventh- to thirteenth-century Annales Cambriæ,[16] and the thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Brut y Tywysogyon reveal that the Kingdom of Strathclyde was wasted by the English.[17] The ninth- to twelfth-century Anglo-Saxon Chronicle offers more information, and relates that Edmund I, King of the English harried across the land of the Cumbrians, and let the region to Máel Coluim mac Domnaill.[18] Similarly, the twelfth-century Historia Anglorum records that the English ravaged the realm, and that Edmund commended the lands to Máel Coluim mac Domnaill who had agreed to assist him by land and sea.[19] According to the version of events preserved by the thirteenth-century Wendover[20] and Paris versions of Flores historiarum, Edmund had two of Dyfnwal's sons blinded.[21] If these sources are to be believed, they could reveal that the two princes had been English hostages before hostilities broke out, or that they were prisoners captured in the midst of the campaign.[22] The ritual blinding of kings was not an unknown act in contemporary Britain and Ireland,[23] and it is possible that Edmund may have meant to deprive Dyfnwal of a royal heir.[24]

The gruesome fate inflicted upon Dyfnwal's sons could reveal that their father was regarded to have broken certain pledges rendered to the English.[25] One possibility is that Dyfnwal was punished for harbouring insular Scandinavian potentates.[26] Whatever lay behind the campaign, it could have been utilised by the English Cerdicing dynasty as a way to overawe and intimidate neighbouring potentates.[27] Máel Coluim was probably a younger son of Dyfnwal, and not one of the sons mutilated by the English. The Gaelic name borne by Máel Coluim could indicate that he was born during a period of Scottish dominance over the Cumbrian realm, or that he was born during a time of relatively warm relations between the Scots and Cumbrians.[28]

Rhydderch and conflict with the Scots

After the death of Illulb mac Custantín, King of Alba in 962, the Scottish kingship appears to have been taken up by Dub mac Maíl Choluim, a man who was in turn replaced by Illulb's son, Cuilén.[30] The latter's short reign appears to have been relatively uneventful.[31] It nevertheless came to a violent end in 971, and there is reason to suspect that Cuilén's killer was a son of Dyfnwal.[32] The ninth- to twelfth-century Chronicle of the Kings of Alba reports that the killer was a certain Rhydderch ap Dyfnwal, a man who slew Cuilén for the sake of his own daughter.[33] The thirteenth-century Verse Chronicle,[34] the twelfth- to thirteenth-century Chronicle of Melrose,[35] and the fourteenth-century Chronica gentis Scotorum likewise identify Cuilén's killer as Rhydderch, the father of an abducted daughter raped by the Scottish king.[36] Although there is no specific evidence that Rhydderch was himself a king,[37] the fact that Cuilén was involved with his daughter, coupled with the fact that his warband was evidently strong enough to overcome that of Cuilén, suggests that Rhydderch must have been a man of eminent standing.[38]

Cuilén seems to have been succeeded by his kinsman Cináed mac Maíl Choluim.[40] One of the latter's first acts as King of Alba was evidently an invasion of the Kingdom of Strathclyde.[41] This campaign could well have been a retaliatory response to Cuilén's killing,[42] carried out in the context of crushing a British affront to Scottish authority.[43] In any event, Cináed's invasion ended in defeat,[44] a fact which coupled with Cuilén's killing reveals that the Cumbrian realm was indeed a power to be reckoned with.[45] Whilst it is conceivable that Rhydderch could have succeeded Dyfnwal by the time of Cuilén's fall,[46] another possibility is that Dyfnwal was still the king, and that Cináed's strike into Cumbrian territory was the last conflict of Dyfnwal's reign.[47] In fact, it could have been at about this point when Máel Coluim took up the kingship.[48] According to the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba, Cináed constructed some sort of fortification on the River Forth, perhaps the strategically located Fords of Frew near Stirling.[49] One possibility is that this engineering project was undertaken in the context of limiting Cumbrian incursions.[50]

Máel Coluim and an assembly of kings

There is evidence to suggest that both Máel Coluim[52] and his father were amongst the assembled kings said to have convened with Edgar at Chester in 973.[53] According to the "D", "E", and "F" versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, after having been consecrated king that year, this English monarch assembled a massive naval force and met with six kings at Chester.[54] By the tenth century, the number of kings who met with him was alleged to have been eight, as evidenced by the tenth-century Life of St Swithun.[55] By the twelfth century, the eight kings began to be named and were alleged to have rowed Edgar down the River Dee, as evidenced by sources such as the twelfth-century texts Chronicon ex chronicis,[56] Gesta regum Anglorum,[57] and De primo Saxonum adventu,[58] as well as the thirteenth-century Chronica majora,[59] and both the Wendover[60] and Paris versions of Flores historiarum.[61][note 3]

Whilst the symbolic tale of the men rowing Edgar down the river may be an unhistorical embellishment, most of the names accorded to the eight kings can be associated with contemporary rulers, suggesting that some of these men may have taken part in a concord with him.[66][note 4] Although the latter accounts allege that the kings submitted to Edgar, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle merely states that they came to an agreement of cooperation with him, and thus became his efen-wyrhtan ("co-workers", "even-workers", "fellow-workers").[68] One possibility is that the assembly somehow relates to Edmund's attested incursion into Cumbria in 945. According to the same source, when Edmund let Cumbria to Máel Coluim mac Domnaill, he had done so on the condition that the latter would be his mid-wyrhta ("co-worker", "even-worker", "fellow-worker", "together-wright").[69] Less reliable non-contemporary sources such as De primo Saxonum adventu,[70] both the Wendover[71] and Paris versions of Flores historiarum,[72] and Chronica majora allege that Edgar granted Lothian to Cináed in 975.[73] If this supposed grant formed a part of the episode at Chester, it along with the concord of 945 could indicate that the assembly of 975 was not a submission as such, but more of a conference concerning mutual cooperation along the English borderlands.[74] Although the precise chronology of Cumbrian expansion is uncertain, by 927 the southern frontier of the Kingdom of Strathclyde appears to have reached the River Eamont, close to Penrith.[75] As such, the location of the assembly of 973 at Chester would have been a logical site for all parties.[76][note 5]

One of the other named kings was Cináed.[80] Considering the fact that the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle numbers the kings at six, if Cináed was indeed present, it is unlikely that his rival, Cuilén's brother Amlaíb mac Illuilb, was also in attendance.[81] Although the chronology concerning the reigns of Cináed and Amlaíb mac Illuilb is uncertain[82]—with Amlaíb mac Illuilb perhaps reigning from 971/976–977[83] and Cináed from 971/977–995[81]—the part played by the King of Alba at the assembly could well have concerned the frontier of his realm.[84] One of the other named kings seems to have been Maccus mac Arailt,[85] whilst another could have been this man's brother, Gofraid.[86] These two Islesmen may have been regarded a threats by the Scots[84] and Cumbrians.[81] Maccus and Gofraid are recorded to have devastated Anglesey at the beginning of the decade,[87] which could indicate that Edgar's assembly was undertaken as a means to counter the menace posed by these energetic insular Scandinavians.[88] In fact, there is evidence to suggest that, as a consequence of the assembly at Chester, the brothers may have turned their attention from the British mainland westwards towards Ireland.[89]

Another aspect of the assembly may have concerned the remarkable rising power of Amlaíb Cúarán in Ireland.[91] Edgar may have wished to not only reign in men such as Maccus and Gofraid, but prevent them—and the Scots and Cumbrians—from affiliating themselves with Amlaíb Cúarán, and recognising the latter's authority in the Irish Sea region.[92] Another factor concerning Edgar, and his Scottish and Cumbrian counterparts, may have been the stability of the northern English frontier. For example, a certain Thored Gunnerson is recorded to have ravaged Westmorland in 966, an action that may have been undertaken by the English in the context of a response to Cumbrian southward expansion.[93][note 6] Although the Scottish invasion of Cumbrian and English territory unleashed after Cináed's inauguration could have been intended to tackle Cumbrian opposition,[42] another possibility is that the campaign could have been executed as a way to counter any occupation of Cumbrian territories by Thored.[96]

Máel Coluim's reign and death

Both Dyfnwal[97] and Edgar died in 975.[98] According to various Irish annals, Dyfnwal met his end whilst undertaking a pilgrimage.[99] Surviving sources fail to note the Cumbrian realm between the obituaries of Dyfnwal in 975 and Máel Coluim in 997.[100] Quite when Dyfnwal ceased to possess the kingship is uncertain. On one hand, there is reason to suspect that Rhydderch possessed power in 971.[38] On the other hand, it is also possible that Dyfnwal was still reigning in 973.[101] In fact, this could have been the point when he ceded power to Máel Coluim: conceivably as a consequence of Rhydderch's assassination of Cuilén two years beforehand.[102] Alternately, Dyfnwal may have retained royal control until setting off upon his pilgrimage.[103] If correct, it could have been Edgar's death that precipitated this final trek, and the transference of the Cumbrian kingship to Máel Coluim.[81][note 7]

Máel Coluim's part in the assembly could have partly concerned his father's impending pilgrimage, and that he sought surety for Dyfnwal's safe passage through Edgar's realm.[84] The fact that Máel Coluim is identified as one of the assembled kings could indicate that Dyfnwal had relinquished control to him at some point before the convention.[106] Conversely, Máel Coluim's title could instead indicate that he merely represented his aged father,[107] and acted as regent.[108] Evidence that Máel Coluim had indeed assumed the kingship before the assembly may exist in the record of a certain Malcolm dux who witnessed an English royal charter in 970 at Woolmer.[109] Although the authenticity of this document is questionable, the attested Malcolm could well be identical to Máel Coluim himself.[110][note 9] If Máel Coluim was indeed king in 973, Dyfnwal's role at the assembly may have been that of an 'elder statesman' of sorts—possibly serving as an adviser or mentor—especially considering his decades of experience in international affairs.[112][note 10]

And Mael Coluim, with hundreds of deeds, before the hands of the land of the Britons, with the bright hospitality of every good battle, the good son of Domnall, son of Eogan.

— excerpt from Saltair na Rann praising Máel Coluim, and proclaiming his descent from Dyfnwal ab Owain and Owain ap Dyfnwal.[114]

If Máel Coluim succeeded Dyfnwal, it could mean that Rhydderch—if he was indeed Máel Coluim's brother—was either dead or unable to reign as king. Whilst it is possible that the sons of Dyfnwal maimed by the English in 945 were still alive in the 970s,[47] the horrific injuries endured by these men would have meant that they were deemed unfit to rule.[115] Notwithstanding the uncertainties surrounding his accession, Máel Coluim's reign was evidently unremarkable.[116] Certainly, no source records Scottish-Cumbrian political relations at about the inception of Máel Coluim's reign,[117] although the fact that Dyfnwal left for Rome could be evidence that the latter did not regard the realm or dynasty to be threatened during his absence.[118]

Máel Coluim—alongside contemporary Irish, English, and Frankish kings—is commemorated by several lines of panegyric verse preserved by the tenth-century Saltair na Rann.[119] He died in 997, the same year as his northern counterpart, Custantín mac Cuiléin, King of Alba.[120] Máel Coluim's demise is recorded by the Annals of Clonmacnoise,[121] the Annals of Ulster,[122] Chronicon Scotorum,[123] and the Annals of Tigernach. The latter styles him "king of the north Britons".[124] Máel Coluim seems to have been succeeded by a brother, Owain.[125] The latter appears to have been succeeded by Owain Foel,[126] a man who may well have been a son of Máel Coluim.[127]

Notes

- ^ Since the 2000s academics have accorded Máel Coluim various personal names in English secondary sources: Mael Colaim,[2] Máel Coluim,[3] Mael Coluim,[4] Maelcoluim,[5] and Malcolm.[6] Since the 2000s academics have accorded Máel Coluim various patronyms in English secondary sources: Máel Coluim mac Domnaill,[7] and Malcolm ap Dyfnwal.[8]

- ^ The Gaelic personal name Máel Coluim means "servant of St Columba". This name was borne by Máel Coluim, son of the king of the Cumbrians, a man who appears to have been a member of the Strathclyde dynasty, and may well have been a descendant of Máel Coluim himself.[13] The Welsh personal name Dyfnwal is a cognate of the Gaelic Domnall.[14]

- ^ Another source linking Dyfnwal and Máel Coluim to the assembly is the Chronicle of Melrose.[62] If it was not Dyfnwal who attended the assembly, another possibility is that the like-named attendee was Domnall ua Néill, King of Tara.[63]

- ^ Two of the kings are accorded names are of uncertain meaning.[67]

- ^ At about the same time as the assembly, De primo Saxonum adventu also notes that Edgar partitioned the Northumbrian ealdormanry into northern and southern divisions, split between the Tees and Myreforth. If the latter location refers to the mud flats between the River Esk and the Solway Firth,[77] it would reveal that what is today Cumberland had fallen outwith Cumbrian royal authority and into the hands of the English.[78]

- ^ According to the Life of St Cathróe, after Dyfnwal escorted Cathróe to the frontier of his realm, the latter was then escorted by a certain Gunderic to the domain of Erich at York.[94] It is possible that Gunderico is identical to Thored's father, and identical to the Gunner who appears is charter evidence from 931–963.[95]

- ^ In fact, the upheaval caused by the absence of Dyfnwal and Edgar could well have contributed to Cináed's final elimination of Amlaíb mac Illuilb in 997.[81]

- ^ Only three rulers of the Kingdom of Strathclyde were styled King of the Cumbrians: Máel Coluim himself, Máel Coluim's father, and Máel Coluim's grandfather, Owain ap Dyfnwal.[105]

- ^ This charter is composed of Latin and Old English text. The document may be evidence of Scottish and Cumbrian submission to the English. For example, one place the text reads in Latin: "I, Edgar, ruler of the beloved island of Albion, subjected to us of the rule of the Scots and Cumbrians and the Britons and of all regions round about ...". The corresponding Old English text reads: "I, Edgar, exalted as king over the English people by His [God's] grace, and He has now subjected to my authority the Scots and Cumbrians and also the Britons and all that this island has inside ...".[111]

- ^ If Máel Coluim was indeed king, the attestation of Malcolm dux would be the only record of a foreign king witnessing one of Edgar's charters.[113]

Citations

- ^ Davidson (2002) p. 142 n. 149; Arnold (1885) p. 372; Cotton MS Domitian A VIII (n.d.).

- ^ Downham (2007).

- ^ Clarkson (2014); Edmonds (2014); Charles-Edwards (2013b); Oram (2011); Aird (2009); Davidson (2002); Hudson (1996).

- ^ Minard (2012); Parsons (2011); Woolf (2007); Busse (2006c); Minard (2006); Broun (2004c); Hicks (2003); Thornton (2001).

- ^ Duncan (2002).

- ^ Williams (2014); Walker (2013); Clarkson (2012); Minard (2012); Clarkson (2010); Keynes (2008); Breeze (2007); Macquarrie (2004); Hicks (2003); Duncan (2002); Hudson (2002); Jayakumar (2002).

- ^ Charles-Edwards (2013b).

- ^ Clarkson (2010).

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. genealogical tables; Charles-Edwards (2013b) p. 572 fig. 17.4; Clarkson (2010) ch. genealogical tables; Woolf (2007) p. 238 tab. 6.4; Broun (2004c) p. 135 tab.; Macquarrie (1998) pp. 6, 16; Hudson (1994) p. 173 genealogy 6.

- ^ Thornton (2001) p. 67.

- ^ Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 44.

- ^ Parsons (2011) p. 129; Woolf (2007) p. 184.

- ^ Clarkson (2013) p. 25.

- ^ Woolf (2007) pp. xiii, 184, 184 n. 17; Koch (2006); Bruford (2000) pp. 64, 65 n. 76; Schrijver (1995) p. 81.

- ^ Royal MS 14 B VI (n.d.).

- ^ Gough-Cooper (2015a) p. 27 § a509.3; Keynes (2015) pp. 95–96; Clarkson (2014) ch. 6 ¶ 14, 6 n. 19; Halloran (2011) p. 308, 308 n. 40; Woolf (2010) p. 228, 228 n. 27; Downham (2007) p. 153; Woolf (2007) p. 183; Downham (2003) p. 42; Hicks (2003) p. 39; Alcock (1975–1976) p. 106; Anderson, AO (1922) p. 449.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 6 ¶ 15; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 25; Downham (2003) p. 42; Hicks (2003) p. 39; Anderson, AO (1922) p. 449; Rhŷs (1890) p. 261; Williams Ab Ithel (1860) pp. 20–21.

- ^ Gough-Cooper (2015a) p. 27 n. 191; Keynes (2015) pp. 95–96; McGuigan (2015) pp. 83, 139–140; McLeod (2015) p. 4; Molyneaux (2015) pp. 33, 52–53, 76; Clarkson (2014) chs. 1 ¶ 10, 6 ¶ 11, 6 n. 18, 6 ¶ 20; Walker (2013) ch. 4 ¶ 5; Halloran (2011) p. 307, 307 n. 36; Molyneaux (2011) pp. 66, 66 n. 27, 69, 70, 73, 88; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶¶ 25–27; Woolf (2010) p. 228, 228 n. 26; Downham (2007) p. 153; Woolf (2007) p. 183; Clancy (2006); Williams (2004b); Downham (2003) p. 42; Hicks (2003) p. 16 n. 35; Duncan (2002) p. 23; Thornton (2001) p. 78, 78 n. 114; O'Keeffe (2001) p. 80; Williams (1999) p. 86; Whitelock (1996) p. 224; Smyth (1989) pp. 205–206; Alcock (1975–1976) p. 106; Stenton (1963) p. 355; Anderson, AO (1908) p. 74, 74 n. 3; Thorpe (1861) pp. 212–213.

- ^ Holland (2016) ch. Malmesbury ¶ 7; Clarkson (2014) ch. 6 ¶ 11, 6 n. 20; Anderson, AO (1908) p. 74 nn. 4–5; Arnold (1879) p. 162 bk. 5 ch. 21; Forester (1853) p. 172 bk. 5.

- ^ Firth (2016) pp. 24–25; McGuigan (2015) p. 139; Molyneaux (2015) pp. 33, 61, 76; Clarkson (2014) ch. 6 ¶¶ 12–13, 6 n. 21; Halloran (2011) p. 308; Molyneaux (2011) pp. 66, 66 n. 27, 70; Woolf (2007) p. 183; Duncan (2002) p. 23; Thornton (2001) p. 78, 78 n. 114; Hudson (1994) p. 174 n. 12; Stenton (1963) p. 355; Anderson, AO (1908) p. 74 n. 5; Giles (1849) pp. 252–253; Coxe (1841) p. 398.

- ^ McGuigan (2015) p. 139; Luard (2012) p. 500; Halloran (2011) p. 308, 308 n. 41; Yonge (1853) p. 473.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 6 ¶ 14; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 25.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 6 n. 23.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) chs. 6 ¶ 14, 7 ¶ 5.

- ^ Holland (2016) ch. Malmesbury ¶ 5; Molyneaux (2015) pp. 77–78; Woolf (2007) p. 183.

- ^ Oram (2011) ch. 2.

- ^ Molyneaux (2015) pp. 33, 77–78.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 7 ¶ 5.

- ^ Anderson, AO (1922) p. 476; Stevenson, J (1835) p. 226; Cotton MS Faustina B IX (n.d.).

- ^ Broun (2004a).

- ^ Walker (2013) ch. 4 ¶ 23.

- ^ Broun (2015); Clarkson (2014) ch. 7 ¶ 6; Clarkson (2012) ch. 9 ¶¶ 28–29; Oram (2011) chs. 2, 5; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 29; Busse (2006b); Busse (2006c); Broun (2004c) p. 135 tab.; Macquarrie (2004); Macquarrie (1998) pp. 6, 16; Hudson (1994) pp. 173 genealogy 6, 174 n. 10; Williams; Smyth; Kirby (1991) pp. 92, 104.

- ^ Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 29; Macquarrie (1998) p. 16; Anderson, AO (1922) p. 476, 476 n. 1; Skene (1867) p. 151.

- ^ Broun (2005) pp. 87–88 n. 37; Skene (1867) p. 179.

- ^ Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶¶ 32–33; Woolf (2007) p. 204; Macquarrie (2004); Hicks (2003) pp. 40–41; Anderson, AO (1922) p. 476; Stevenson, J (1835) p. 226.

- ^ Hudson (1994) pp. 93, 174 n. 10; Skene (1872) pp. 161–162 bk 4 ch. 27; Skene (1871) pp. 169–170 bk 4.

- ^ Macquarrie (2004); Thornton (2001) p. 67 n. 66.

- ^ a b Macquarrie (2004).

- ^ a b The Annals of Tigernach (2016) § 997.3; Annals of Tigernach (2005) § 997.3; Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. B. 488 (n.d.).

- ^ Broun (2004a); Broun (2004b).

- ^ Williams (2014); Walker (2013) ch. 4 ¶ 25; Clarkson (2012) ch. 9 ¶ 30; Oram (2011) ch. 5; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 35; Woolf (2009) p. 259; Busse (2006a); Broun (2004b); Hudson (1998) pp. 151, 161; Anderson, AO (1922) p. 512; Skene (1867) p. 10.

- ^ a b Walker (2013) ch. 4 ¶ 25; Woolf (2009) p. 259.

- ^ Walker (2013) ch. 4 ¶ 25.

- ^ Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 35; Broun (2004b).

- ^ McGuigan (2015) p. 140; Clarkson (2012) ch. 9 ¶ 28; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 35.

- ^ Thornton (2001) p. 67 n. 66.

- ^ a b Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 35.

- ^ Hicks (2003) p. 44 n. 107.

- ^ McGuigan (2015) p. 149; Clarkson (2012) ch. 9 ¶ 30; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 37; Broun (2007) p. 54; Hicks (2003) pp. 41–42; Davidson (2002) pp. 147–148, 147 n. 167; Hudson (1998) pp. 151, 161; Hudson (1994) p. 96; Breeze (1992); Anderson, AO (1922) p. 512; Skene (1867) p. 10.

- ^ Clarkson (2012) ch. 9 ¶ 30; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 37.

- ^ Rhŷs (1890) p. 262; Williams Ab Ithel (1860) pp. 26–27; Jesus College MS. 111 (n.d.); Oxford Jesus College MS. 111 (n.d.).

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 7 ¶ 12; Edmonds (2014) p. 206; Williams (2014); Charles-Edwards (2013b) pp. 543–544; Walker (2013) ch. 4 ¶¶ 30, 36; Clarkson (2012) ch. 9 ¶ 29; Minard (2012); Aird (2009) p. 309; Breeze (2007) pp. 154–155; Downham (2007) p. 167; Minard (2006); Macquarrie (2004); Williams (2004); Davidson (2002) pp. 142–143; Duncan (2002) p. 23 n. 53; Jayakumar (2002) p. 34; Thornton (2001) pp. 66–67; Williams (1999) pp. 88, 116; Macquarrie (1998) p. 16; Hudson (1994) p. 174 n. 9; Jennings (1994) p. 215; Williams; Smyth; Kirby (1991) pp. 104, 124; Stenton (1963) p. 324.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 7 ¶ 12; Edmonds (2014) p. 206; Williams (2014); Charles-Edwards (2013b) pp. 543–544; Clarkson (2012) ch. 9 ¶ 29; Oram (2011) ch. 2; Woolf (2009) p. 259; Breeze (2007) pp. 154–155; Downham (2007) pp. 124, 167; Woolf (2007) p. 208; Macquarrie (2004); Williams (2004); Hicks (2003) p. 42; Davidson (2002) p. 143; Jayakumar (2002) p. 34; Thornton (2001) pp. 54–55, 67; Macquarrie (1998) p. 16; Williams; Smyth; Kirby (1991) pp. 104, 124; Stenton (1963) p. 324.

- ^ Firth (2018) p. 48; Holland (2016) ch. Malmesbury ¶ 6; McGuigan (2015) pp. 143–144, 144 n. 466; Molyneaux (2015) p. 34; Clarkson (2014) ch. 7 ¶¶ 9–10, 7 n. 11; Williams (2014); Charles-Edwards (2013b) pp. 543–544; Walker (2013) ch. 4 ¶ 30; Molyneaux (2011) pp. 66, 69, 88; Breeze (2007) p. 153; Downham (2007) p. 124; Matthews (2007) p. 10; Woolf (2007) pp. 207–208; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 218; Irvine (2004) p. 59; Karkov (2004) p. 108; Williams (2004); Davidson (2002) pp. 138, 140, 140 n. 140, 144; Thornton (2001) p. 50; Baker (2000) pp. 83–84; Williams (1999) pp. 88, 116, 191 n. 50; Whitelock (1996) pp. 229–230; Hudson (1994) p. 97; Stenton (1963) p. 364; Anderson, AO (1908) pp. 75–76; Stevenson, WH (1898); Thorpe (1861) pp. 225–227.

- ^ Edmonds (2015) p. 61 n. 94; Keynes (2015) pp. 113–114; McGuigan (2015) pp. 143–144; Edmonds (2014) p. 206, 206 n. 60; Williams (2014); Molyneaux (2011) p. 67; Breeze (2007) p. 154; Downham (2007) p. 124; Matthews (2007) p. 10; Karkov (2004) p. 108; Williams (2004); Davidson (2002) pp. 140–141, 141 n. 145, 145; Thornton (2001) p. 51; Williams (1999) pp. 191 n. 50, 203 n. 71; Hudson (1994) pp. 97–98; Jennings (1994) pp. 213–214; Anderson, AO (1922) p. 479 n. 1; Stevenson, WH (1898); Skeat (1881) pp. 468–469.

- ^ Firth (2018) p. 48; Edmonds (2015) p. 61 n. 94; McGuigan (2015) pp. 143–144, n. 466; Keynes (2015) p. 114; Clarkson (2014) ch. 7 ¶¶ 12–14; Edmonds (2014) p. 206; Williams (2014); Charles-Edwards (2013b) pp. 543–544; Walker (2013) ch. 4 ¶ 30; Molyneaux (2011) pp. 66–67; Breeze (2007) p. 153; Downham (2007) p. 124; Matthews (2007) p. 11; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 218; Karkov (2004) p. 108; Williams (2004); Davidson (2002) pp. 13, 134, 134 n. 111, 142, 145; Thornton (2001) pp. 57–58; Williams (1999) pp. 116, 191 n. 50; Whitelock (1996) p. 230 n. 1; Hudson (1994) p. 97; Jennings (1994) p. 213; Smyth (1989) pp. 226–227; Stenton (1963) p. 364; Anderson, AO (1908) pp. 76–77; Stevenson, WH (1898); Forester (1854) pp. 104–105; Stevenson, J (1853) pp. 247–248; Thorpe (1848) pp. 142–143.

- ^ Edmonds (2015) p. 61 n. 94; Keynes (2015) p. 114; McGuigan (2015) p. 144, n. 466; Edmonds (2014) p. 206; Williams (2014); Charles-Edwards (2013b) pp. 543–544; Molyneaux (2011) pp. 66–67; Breeze (2007) p. 153; Downham (2007) p. 124; Matthews (2007) pp. 10–11; Karkov (2004) p. 108, 108 n. 123; Williams (2004); Davidson (2002) pp. 143, 145; Thornton (2001) pp. 59–60; Hudson (1994) p. 97; Anderson, AO (1908) p. 77 n. 1; Stevenson, WH (1898); Giles (1847) p. 147 bk. 2 ch. 8; Hardy (1840) p. 236 bk. 2 ch. 148.

- ^ McGuigan (2015) p. 144, 144 n. 469; Davidson (2002) p. 142, 142 n. 149, 145; Thornton (2001) pp. 60–61; Anderson, AO (1908) p. 76 n. 2; Arnold (1885) p. 372.

- ^ Thornton (2001) p. 60; Luard (1872) pp. 466–467.

- ^ Thornton (2001) p. 60; Giles (1849) pp. 263–264; Coxe (1841) p. 415.

- ^ Luard (2012) p. 513; Thornton (2001) p. 60; Yonge (1853) p. 484.

- ^ Hicks (2003) p. 42; Anderson, AO (1922) pp. 478–479; Stevenson, J (1856) p. 100; Stevenson, J (1835) p. 34.

- ^ Davidson (2002) pp. 146–147.

- ^ Cassell's History of England (1909) p. 53.

- ^ Williams (2004).

- ^ Thornton (2001) p. 74.

- ^ Thornton (2001) pp. 67–74.

- ^ Davidson (2002) pp. 66–67, 140; Davidson (2001) p. 208; Thornton (2001) pp. 77–78.

- ^ Hicks (2003) p. 16 n. 35; Davidson (2002) pp. 115–116, 140; Davidson (2001) p. 208; Thornton (2001) pp. 77–78; Whitelock (1996) p. 224; Anderson, AO (1908) p. 74; Thorpe (1861) pp. 212–213.

- ^ Keynes (2008) p. 51; Woolf (2007) p. 211; Thornton (2001) pp. 65–66; Anderson, MO (1960) p. 104; Anderson, AO (1908) p. 77; Arnold (1885) p. 382.

- ^ Anderson, MO (1960) p. 107, 107 n. 1; Giles (1849) p. 264; Coxe (1841) p. 416.

- ^ Luard (2012) p. 513; Thornton (2001) pp. 65–66; Anderson, MO (1960) p. 107, 107 n. 1; Yonge (1853) p. 485.

- ^ Anderson, MO (1960) p. 107, 107 nn. 1, 4; Anderson, AO (1908) pp. 77–78 n. 6; Luard (1872) pp. 467–468.

- ^ Downham (2007) p. 125; Williams (2004); Davidson (2002) p. 5; Thornton (2001) pp. 78–79.

- ^ Dumville (2018) pp. 72, 110, 118; Edmonds (2015) pp. 44, 53; Charles-Edwards (2013a) p. 20; Charles-Edwards (2013b) pp. 9, 481; Parsons (2011) p. 138 n. 62; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 10; Davies (2009) p. 73, 73 n. 40; Downham (2007) p. 165; Clancy (2006); Todd (2005) p. 96; Stenton (1963) p. 328.

- ^ Barrow (2001) p. 89.

- ^ McGuigan (2015) p. 147; Aird (2009) p. 309; Davidson (2002) p. 149, 149 n. 172; Duncan (2002) p. 24; Hudson (1994) p. 140; Anderson, AO (1908) p. 77; Arnold (1885) p. 382.

- ^ Duncan (2002) pp. 24–25.

- ^ O'Keeffe (2001) p. 81; Whitelock (1996) p. 230; Thorpe (1861) p. 226; Cotton MS Tiberius B I (n.d.).

- ^ Aird (2009) p. 309; Woolf (2009) p. 259; Breeze (2007) p. 155; Downham (2007) p. 124; Woolf (2007) p. 208; Broun (2004b); Davidson (2002) p. 142.

- ^ a b c d e Woolf (2007) p. 208.

- ^ Woolf (2007) pp. 208–209.

- ^ Duncan (2002) pp. 21–22; Hudson (1994) p. 93.

- ^ a b c Matthews (2007) p. 25.

- ^ Jennings (2015); Wadden (2015) pp. 27–28; Clarkson (2014) ch. 7 ¶ 12; Williams (2014); Charles-Edwards (2013b) p. 543; Walker (2013) ch. 4 ¶ 31; Woolf (2009) p. 259; Breeze (2007) p. 155; Downham (2007) pp. 124–125, 167, 222; Matthews (2007) p. 25; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 218; Davidson (2002) pp. 143, 146, 151; Jayakumar (2002) p. 34; Williams (1999) p. 116; Hudson (1994) p. 97; Jennings (1994) pp. 213–214; Stenton (1963) p. 364.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 7 ¶ 12; Charles-Edwards (2013b) p. 544; Breeze (2007) p. 156; Downham (2007) pp. 125 n. 10, 222; Matthews (2007) p. 25; Davidson (2002) pp. 143, 146, 151; Jayakumar (2002) p. 34.

- ^ Gough-Cooper (2015b) p. 43 § b993.1; Williams (2014); Downham (2007) p. 192; Matthews (2007) pp. 9, 25; Woolf (2007) pp. 206–207; Davidson (2002) p. 151; Anderson, AO (1922) pp. 478–479 n. 6; Rhŷs (1890) p. 262; Williams Ab Ithel (1860) pp. 24–25.

- ^ Charles-Edwards (2013b) p. 545; Downham (2007) pp. 222–223; Matthews (2007) pp. 9, 15; Woolf (2007) pp. 207–208.

- ^ Downham (2007) pp. 126–127, 222–223; Woolf (2007) p. 208.

- ^ Baker (2000) p. 83; Cotton MS Domitian A VIII (n.d.).

- ^ Charles-Edwards (2013b) p. 545; Davidson (2002) p. 147.

- ^ Charles-Edwards (2013b) p. 545.

- ^ Williams (2014); Williams (2004); Whitelock (1996) p. 229; Anderson, AO (1922) p. 472; Thorpe (1861) p. 223.

- ^ McGuigan (2015) p. 98; Anderson, AO (1922) p. 441; Skene (1867) p. 116; Colganvm (1645) p. 497.

- ^ McGuigan (2015) pp. 98–99.

- ^ Walker (2013) ch. 4 ¶ 26.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 7 ¶ 17; Williams (2014); Walker (2013) ch. 4 ¶¶ 30, 36; Minard (2012); Oram (2011) ch. 2; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 41; Woolf (2007) p. 184; Busse (2006c); Minard (2006); Broun (2004c) pp. 128–129; Macquarrie (2004); Davidson (2002) pp. 39, 146; Macquarrie (1998) pp. 15–16; Hudson (1994) pp. 101, 174 n. 8; Williams; Smyth; Kirby (1991) p. 104.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 7 ¶ 17; Williams (2014); Walker (2013) ch. 4 ¶ 35; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 41; Woolf (2007) p. 208; Williams; Smyth; Kirby (1991) p. 124.

- ^ The Annals of Ulster (2017) § 975.2; The Annals of Tigernach (2016) § 975.3; Clarkson (2014) ch. 7 ¶ 17, 7 n. 19; Walker (2013) ch. 4 ¶ 36; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 41; The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 975.2; Woolf (2007) p. 184; Annals of Tigernach (2005) § 975.3; Broun (2004c) pp. 128–129; Macquarrie (2004); Hicks (2003) p. 42; Davidson (2002) pp. 39, 146; Macquarrie (1998) pp. 15–16; Hudson (1994) p. 174 n. 8; Anderson, AO (1922) p. 480, 480 n. 7.

- ^ Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 41.

- ^ Walker (2013) ch. 4 ¶ 30; Busse (2006c); Thornton (2001) p. 55.

- ^ Walker (2013) ch. 4 ¶ 36; Oram (2011) ch. 2.

- ^ Walker (2013) ch. 4 ¶ 30; Busse (2006c); Hudson (1994) p. 101; Stenton (1963) p. 364.

- ^ Anderson, AO (1922) p. 478; Stevenson, J (1856) p. 100; Stevenson, J (1835) p. 34; Cotton MS Faustina B IX (n.d.).

- ^ Minard (2012); Minard (2006).

- ^ Williams (2014); Walker (2013) ch. 4 ¶ 30; Clarkson (2012) ch. 9 ¶ 29; Macquarrie (2004); Davidson (2002) p. 146; Williams; Smyth; Kirby (1991) p. 104.

- ^ Walker (2013) ch. 4 ¶ 30.

- ^ Breeze (2007) p. 154.

- ^ McGuigan (2015) p. 101, 101 n. 302; Clarkson (2014) ch. 7 ¶ 5, 7 n. 3; Birch (1893) pp. 557–560 § 1266; Thorpe (1865) pp. 237–243; Malcolm 4 (n.d.); S 779 (n.d.).

- ^ Molyneaux (2015) p. 57 n. 45; Clarkson (2014) ch. 7 ¶ 5; Charles-Edwards (2013b) p. 544; Molyneaux (2011) p. 66; Keynes (2008) p. 50 n. 232; Davidson (2002) pp. 147, 147 n. 166, 152; Thornton (2001) p. 71; Hudson (1994) p. 174 n. 9; Malcolm 4 (n.d.).

- ^ Thornton (2001) p. 52, 52 n. 6; Birch (1893) pp. 557–560 § 1266; Thorpe (1865) pp. 237–243; S 779 (n.d.).

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 7 ¶ 12; Clarkson (2012) ch. 9 ¶ 29; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 35.

- ^ Davidson (2002) pp. 147, 152.

- ^ Saltair na Rann (2011) §§ 2373–2376; Hudson (1994) pp. 101, 174 nn. 8–9; Mac Eoin (1961) pp. 53 §§ 2373–2376, 55–56; Saltair na Rann (n.d.) §§ 2373–2376.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 7 ¶ 5; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 35.

- ^ Busse (2006c).

- ^ Clarkson (2012) ch. 9 ¶ 29.

- ^ Hicks (2003) p. 42.

- ^ McGuigan (2015) p. 140; Saltair na Rann (2011) §§ 2373–2376; Hudson (2002) pp. 34, 36; Hudson (1996) p. 102; Hudson (1994) pp. 101, 174 nn. 8–9; Hudson (1991) p. 147; Mac Eoin (1961) pp. 53 §§ 2373–2376, 55–56; Saltair na Rann (n.d.) §§ 2373–2376.

- ^ Woolf (2007) p. 222.

- ^ Hicks (2003) p. 31; Thornton (2001) p. 66; Hudson (1994) p. 174 n. 9; Mac Eoin (1961) p. 56; Anderson, AO (1922) p. 517 n. 5; Murphy (1896) p. 163.

- ^ The Annals of Ulster (2017) § 997.5; The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 997.5; Woolf (2007) p. 184, 184 n. 17; Davidson (2002) p. 39; Thornton (2001) p. 66; Hudson (1994) p. 174 n. 9; Mac Eoin (1961) p. 56; Anderson, AO (1922) p. 517 n. 5.

- ^ Chronicon Scotorum (2012) § 997; Chronicon Scotorum (2010) § 997; Thornton (2001) p. 66; Hudson (1994) p. 174 n. 9; Mac Eoin (1961) p. 56; Anderson, AO (1922) p. 517 n. 5.

- ^ The Annals of Tigernach (2016) § 997.3; Annals of Tigernach (2005) § 997.3; Macquarrie (2004); Hicks (2003) p. 31; Thornton (2001) p. 66; Macquarrie (1998) p. 16; Hudson (1994) p. 174 n. 9; Mac Eoin (1961) p. 56; Anderson, AO (1922) p. 517.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 7 ¶ 17; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 41; Woolf (2007) pp. 222, 233, 236.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 9 ¶ 47.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) chs. genealogical tables, 8 ¶ 7; Charles-Edwards (2013b) p. 572 fig. 17.4; Woolf (2007) pp. 236, 238 tab. 6.4; Broun (2004c) pp. 128 n. 66, 135 tab.; Hicks (2003) p. 44, 44 n. 107; Duncan (2002) pp. 29, 41.

References

Primary sources

- Anderson, AO, ed. (1908). Scottish Annals From English Chroniclers, A.D. 500 to 1286. London: David Nutt. OL 7115802M.

- Anderson, AO, ed. (1922). Early Sources of Scottish History, A.D. 500 to 1286. Vol. 1. London: Oliver and Boyd. OL 14712679M.

- "Annals of Tigernach". Corpus of Electronic Texts (13 April 2005 ed.). University College Cork. 2005. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- Arnold, T, ed. (1879). Henrici Archidiaconi Huntendunensis Historia Anglorum. The History of the English. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. London: Longman & Co. OL 16622993M.

- Arnold, T, ed. (1885). Symeonis Monachi Opera Omnia. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. Vol. 2. London: Longmans & Co.

- Baker, PS, ed. (2000). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: A Collaborative Edition. Vol. 8. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer. ISBN 0 85991 490 9.

- Birch, WDG (1893). Cartularium Saxonicum. Vol. 3. London: Charles J. Clark.

- "Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. B. 488". Early Manuscripts at Oxford University. Oxford Digital Library. n.d. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - "Chronicon Scotorum". Corpus of Electronic Texts (24 March 2010 ed.). University College Cork. 2010. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- "Chronicon Scotorum". Corpus of Electronic Texts (14 May 2012 ed.). University College Cork. 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- Colganvm, I, ed. (1645). Acta Sanctorvm Veteris et Maioris Scotiæ, sev Hiberniæ Sanctorvm Insvlae. Lyon: Everardvm de VVitte.

- "Cotton MS Domitian A VIII". British Library. n.d. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - "Cotton MS Faustina B IX". British Library. n.d. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - "Cotton MS Tiberius B I". British Library. n.d. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Coxe, HE, ed. (1841). Rogeri de Wendover Chronica, sive Flores Historiarum. Bohn's Antiquarian Library. Vol. 1. London: English Historical Society. OL 24871700M.

- Forester, T, ed. (1853). The Chronicle of Henry of Huntingdon: Comprising the History of England, From the Invasion of Julius Cæsar to the Accession of Henry II. Also, the Acts of Stephen, King of England and Duke of Normandy. Bohn's Antiquarian Library. London: Henry G. Bohn. OL 24434761M.

- Forester, T, ed. (1854). The Chronicle of Florence of Worcester, with the Two Continuations: Comprising Annals of English History, From the Departure of the Romans to the Reign of Edward I. Bohn's Antiquarian Library. London: Henry G. Bohn. OL 24871176M.

- Giles, JA, ed. (1847). William of Malmesbury's Chronicle of the Kings of England, From the Earliest Period to the Reign of King Stephen. Bohn's Antiquarian Library. London: Henry G. Bohn.

- Giles, JA, ed. (1849). Roger of Wendover's Flowers of History. Bohn's Antiquarian Library. Vol. 1. London: Henry G. Bohn.

- Gough-Cooper, HW, ed. (2015a). Annales Cambriae: The A Text From British Library, Harley MS 3859, ff. 190r–193r (PDF) (November 2015 ed.) – via Welsh Chronicles Research Group.

- Gough-Cooper, HW, ed. (2015b). Annales Cambriae: The B Text From London, National Archives, MS E164/1, pp. 2–26 (PDF) (September 2015 ed.) – via Welsh Chronicles Research Group.

- Hardy, TD, ed. (1840). Willelmi Malmesbiriensis Monachi Gesta Regum Anglorum Atque Historia Novella. Vol. 1. London: English Historical Society. OL 24871887M.

- Hudson, BT (1998). "'The Scottish Chronicle'". Scottish Historical Review. 77 (2): 129–161. doi:10.3366/shr.1998.77.2.129. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241. JSTOR 25530832.

- Irvine, S, ed. (2004). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: A Collaborative Edition. Vol. 7. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer. ISBN 0 85991 494 1.

- "Jesus College MS. 111". Early Manuscripts at Oxford University. Oxford Digital Library. n.d. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Luard, HR, ed. (1872). Matthæi Parisiensis, Monachi Sancti Albani, Chronica Majora. Vol. 1. London: Longman & Co.

- Luard, HR, ed. (2012) [1890]. Flores Historiarum. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139382960. ISBN 978-1-108-05334-1.

- Mac Eoin, G (1961). "The Date and Authorship of Saltair na Rann". Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie. 28: 51–67. doi:10.1515/zcph.1961.28.1.51. eISSN 1865-889X. ISSN 0084-5302.

- O'Keeffe, KO, ed. (2001). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: A Collaborative Edition. Vol. 5. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer. ISBN 0 85991 491 7.

- "Oxford Jesus College MS. 111 (The Red Book of Hergest)". Welsh Prose 1300–1425. n.d. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - "Royal MS 14 B VI". British Library. n.d. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - "S 779". The Electronic Sawyer: Online Catalogue of Anglo-Saxon Charters. n.d. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - "Saltair na Rann". Corpus of Electronic Texts (22 January 2011 ed.). University College Cork. 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- "Saltair na Rann" (PDF). Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies (School of Celtic Studies). n.d. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Skeat, W, ed. (1881). Ælfric's Lives of Saints. Third series. Vol. 1. London: Early English Text Society.

- Skene, WF, ed. (1867). Chronicles of the Picts, Chronicles of the Scots, and Other Early Memorials of Scottish History. Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House. OL 23286818M.

- Skene, WF, ed. (1871). Johannis de Fordun Chronica Gentis Scotorum. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas. OL 24871486M.

- Skene, WF, ed. (1872). John of Fordun's Chronicle of the Scottish Nation. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas. OL 24871442M.

- Stevenson, J, ed. (1835). Chronica de Mailros. Edinburgh: The Bannatyne Club. OL 13999983M.

- Stevenson, J, ed. (1856). The Church Historians of England. Vol. 4, pt. 1. London: Seeleys.

- Stevenson, J, ed. (1853). The Church Historians of England. Vol. 2, pt. 1. London: Seeleys.

- Murphy, D, ed. (1896). The Annals of Clonmacnoise. Dublin: Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. OL 7064857M.

- "The Annals of Tigernach". Corpus of Electronic Texts (8 February 2016 ed.). University College Cork. 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- "The Annals of Ulster". Corpus of Electronic Texts (29 August 2008 ed.). University College Cork. 2008. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- "The Annals of Ulster". Corpus of Electronic Texts (6 January 2017 ed.). University College Cork. 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- Thorpe, B, ed. (1848). Florentii Wigorniensis Monachi Chronicon ex Chronicis. Vol. 1. London: English Historical Society. OL 24871544M.

- Thorpe, B, ed. (1861). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. Vol. 1. London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts.

- Thorpe, B, ed. (1865). Diplomatarium Anglicum Ævi Saxonici: A Collection of English Charters. London: Macmillan & Co. OL 21774758M.

- Whitelock, D, ed. (1996) [1955]. English Historical Documents, c. 500–1042 (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-43950-3.

- Williams Ab Ithel, J, ed. (1860). Brut y Tywysigion; or, The Chronicle of the Princes. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts. OL 24776516M.

- Yonge, CD, ed. (1853). The Flowers of History. Vol. 1. London: Henry G. Bohn. OL 7154619M.

Secondary sources

- Aird, WM (2009). "Northumbria". In Stafford, P (ed.). A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland, c.500–c.1100. Blackwell Companions to British History. Chichester: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 303–321. ISBN 978-1-405-10628-3.

- Alcock, L (1975–1976). "A Multi-Disciplinary Chronology for Alt Clut, Castle Rock, Dumbarton" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 107: 103–113. eISSN 2056-743X. ISSN 0081-1564.

- Anderson, MO (1960). "Lothian and the Early Scottish Kings". Scottish Historical Review. 39 (2): 98–112. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241. JSTOR 25526601.

- Barrow, J (2001). "Chester's Earliest Regatta? Edgar's Dee-Rowing Revisited". Early Medieval Europe. 10 (1): 81–93. doi:10.1111/1468-0254.00080. eISSN 1468-0254.

- Breeze, A (1992). "The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for 1072 and the Fords of Frew, Scotland". Notes and Queries. 39 (3): 269–270. doi:10.1093/nq/39.3.269. eISSN 1471-6941. ISSN 0029-3970.

- Breeze, A (2007). "Edgar at Chester in 973: A Breton Link?". Northern History. 44 (1): 153–157. doi:10.1179/174587007X165405. eISSN 1745-8706. ISSN 0078-172X.

- Broun, D (2004a). "Culen (d. 971)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6870. Retrieved 13 June 2016. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Broun, D (2004b). "Kenneth II (d. 995)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/15399. Retrieved 3 December 2015. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Broun, D (2004c). "The Welsh Identity of the Kingdom of Strathclyde c.900–c.1200". The Innes Review. 55 (2): 111–180. doi:10.3366/inr.2004.55.2.111. eISSN 1745-5219. ISSN 0020-157X.

- Broun, D (2005). "Contemporary Perspectives on Alexander II's Succession: The Evidence of King-lists". In Oram, RD (ed.). The Reign of Alexander II, 1214–49. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. pp. 79–98. ISBN 90 04 14206 1. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Broun, D (2007). Scottish Independence and the Idea of Britain: From the Picts to Alexander III. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978 0 7486 2360 0.

- Broun, D (2015) [1997]. "Cuilén". In Crowcroft, R; Cannon, J (eds.). The Oxford Companion to British History (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199677832.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-967783-2 – via Oxford Reference.

- Bruford, A (2000). "What Happened to the Caledonians". In Cowan, EJ; McDonald, RA (eds.). Alba: Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. pp. 43–68. ISBN 1-86232-151-5.

- Busse, PE (2006a). "Cinaed mac Mael Choluim". In Koch, JT (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 439. ISBN 1-85109-445-8.

- Busse, PE (2006b). "Cuilén Ring mac Illuilb". In Koch, JT (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 509. ISBN 1-85109-445-8.

- Busse, PE (2006c). "Dyfnwal ab Owain/Domnall mac Eogain". In Koch, JT (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 639. ISBN 1-85109-445-8.

- Cassell's History of England: From the Roman Invasion to the Wars of the Roses. Vol. 1. London: Cassell and Company. 1909. OL 7042010M.

- Charles-Edwards, TM (2013a). "Reflections on Early-Medieval Wales". Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion. 19: 7–23. ISSN 0959-3632.

- Charles-Edwards, TM (2013b). Wales and the Britons, 350–1064. The History of Wales. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821731-2.

- Clancy, TO (2006). "Ystrad Clud". In Koch, JT (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. Vol. 5. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 1818–1821. ISBN 1-85109-445-8.

- Clarkson, T (2010). The Men of the North: The Britons and Southern Scotland (EPUB). Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 978-1-907909-02-3.

- Clarkson, T (2012) [2011]. The Makers of Scotland: Picts, Romans, Gaels and Vikings (EPUB). Edinburgh: Birlinn Limited. ISBN 978-1-907909-01-6.

- Clarkson, T (2013). "The Last King of Strathclyde". History Scotland. 13 (6): 24–27. ISSN 1475-5270.

- Clarkson, T (2014). Strathclyde and the Anglo-Saxons in the Viking Age (EPUB). Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 978-1-907909-25-2.

- Davidson, MR (2001). "The (Non)Submission of the Northern Kings in 920". In Higham, NJ; Hill, DH (eds.). Edward the Elder, 899–924. London: Routledge. pp. 200–211. hdl:1842/23321. ISBN 0-415-21496-3.

- Davidson, MR (2002). Submission and Imperium in the Early Medieval Insular World (PhD thesis). University of Edinburgh. hdl:1842/23321.

- Davies, JR (2009). "Bishop Kentigern Among the Britons". In Boardman, S; Davies, JR; Williamson, E (eds.). Saints' Cults in the Celtic World. Studies in Celtic History. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 66–90. ISBN 978-1-84383-432-8. ISSN 0261-9865.

- Downham, C (2003). "The Chronology of the Last Scandinavian Kings of York, AD 937–954". Northern History. 40 (1): 27–51. doi:10.1179/007817203792207979. eISSN 1745-8706. ISSN 0078-172X.

- Downham, C (2007). Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland: The Dynasty of Ívarr to A.D. 1014. Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-903765-89-0.

- Dumville, DN (2018). "Origins of the Kingdom of the English". In Naismith, R; Woodman, DA (eds.). Writing, Kingship and Power in Anglo-Saxon England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 71–121. doi:10.1017/9781316676066.005. ISBN 978-1-107-16097-2.

- Duncan, AAM (2002). The Kingship of the Scots, 842–1292: Succession and Independence. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0 7486 1626 8.

- Edmonds, F (2014). "The Emergence and Transformation of Medieval Cumbria". Scottish Historical Review. 93 (2): 195–216. doi:10.3366/shr.2014.0216. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241.

- Edmonds, F (2015). "The Expansion of the Kingdom of Strathclyde". Early Medieval Europe. 23 (1): 43–66. doi:10.1111/emed.12087. eISSN 1468-0254.

- Firth, M (2016). "Allegories of Sight: Blinding and Power in Late Anglo-Saxon England". Ceræ: An Australasian Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies. 3: 1–33. ISSN 2204-146X.

- Firth, M (2018). "The Politics of Hegemony and the 'Empires' of Anglo-Saxon England". Ceræ: An Australasian Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies. 5: 27–60. ISSN 2204-146X.

- Forte, A; Oram, RD; Pedersen, F (2005). Viking Empires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82992-2.

- Halloran, K (2011). "Welsh Kings at the English Court, 928–956". The Welsh History Review. 25 (3): 297–313. doi:10.16922/whr.25.3.1. eISSN 0083-792X. ISSN 0043-2431.

- Hicks, DA (2003). Language, History and Onomastics in Medieval Cumbria: An Analysis of the Generative Usage of the Cumbric Habitative Generics Cair and Tref (PhD thesis). University of Edinburgh. hdl:1842/7401.

- Holland, T (2016). Athelstan: The Making of England (EPUB). Penguin Monarchs. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-241-18782-1.

- Hudson, BT (1991). "Historical Literature of Early Scotland". Studies in Scottish Literature. 26 (1): 141–155. ISSN 0039-3770.

- Hudson, BT (1994). Kings of Celtic Scotland. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-29087-3. ISSN 0885-9159 – via Questia.

- Hudson, BT (1996). Prophecy of Berchán: Irish and Scottish High-Kings of the Early Middle Ages. Contributions to the Study of World History. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-29567-0. ISSN 0885-9159.

- Hudson, BT (2002). "The Scottish Gaze". In McDonald, RA (ed.). History, Literature, and Music in Scotland, 700–1560. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 29–59. ISBN 0-8020-3601-5. OL 3623178M.

- Jayakumar, J (2002). "The 'Foreign Policies' of Edgar 'the Peaceable'". In Morillo, S (ed.). The Haskins Society Journal: Studies in Medieval History. Vol. 10. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 17–37. ISBN 0-85115-911-7. ISSN 0963-4959. OL 8277739M.

- Jennings, A (1994). Historical Study of the Gael and Norse in Western Scotland From c.795 to c.1000 (PhD thesis). University of Edinburgh. hdl:1842/15749.

- Jennings, A (2015) [1997]. "Isles, Kingdom of the". In Crowcroft, R; Cannon, J (eds.). The Oxford Companion to British History (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199677832.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-967783-2 – via Oxford Reference.

- Karkov, CE (2004). The Ruler Portraits of Anglo-Saxon England. Anglo-Saxon Studies. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-059-0. ISSN 1475-2468.

- Keynes, S (2008). "Edgar, rex Admirabilis". In Scragg, D (ed.). Edgar, King of the English, 959–975: New Interpretations. Publications of the Manchester Centre for Anglo-Saxon Studies. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 3–58. ISBN 978-1-84383-399-4. ISSN 1478-6710.

- Keynes, S (2015). "The Henry Loyn Memorial Lecture for 2008: Welsh Kings at Anglo-Saxon Royal Assemblies (928–55)". In Gathagan, LL; North, W (eds.). The Haskins Society Journal: Studies in Medieval History. Vol. 26. The Boydell Press. pp. 69–122. ISBN 978-1-78327-071-2. JSTOR 10.7722/j.ctt17mvjs6.9.

- Koch, JT (2006). "Domnall Brecc". In Koch, JT (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 604. ISBN 1-85109-445-8.

- Macquarrie, A (1998) [1993]. "The Kings of Strathclyde, c. 400–1018". In Grant, A; Stringer, KJ (eds.). Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–19. ISBN 0-7486-1110-X.

- Macquarrie, A (2004). "Donald (d. 975)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49382. Retrieved 19 June 2016. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Malcolm 4 (Male)". Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England. n.d. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Matthews, S (2007). "King Edgar, Wales and Chester: The Welsh Dimension in the Ceremony of 973". Northern History. 44 (2): 9–26. doi:10.1179/174587007X208209. eISSN 1745-8706. ISSN 0078-172X.

- McGuigan, N (2015). Neither Scotland nor England: Middle Britain, c.850–1150 (PhD thesis). University of St Andrews. hdl:10023/7829.

- McLeod, S (2015). "The Dubh Gall in Southern Scotland: The Politics of Northumbria, Dublin, and the Community of St Cuthbert in the Viking Age, c. 870–950 CE". Limina: A Journal of Historical and Cultural Studies. 20 (3): 83–103. ISSN 1833-3419.

- Minard, A (2006). "Cumbria". In Koch, JT (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 514–515. ISBN 1-85109-445-8.

- Minard, A (2012). "Cumbria". In Koch, JT; Minard, A (eds.). The Celts: History, Life, and Culture. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 234–235. ISBN 978-1-59884-964-6.

- Molyneaux, G (2011). "Why Were Some Tenth-Century English Kings Presented as Rulers of Britain?". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 21: 59–91. doi:10.1017/S0080440111000041. eISSN 1474-0648. ISSN 0080-4401.

- Molyneaux, G (2015). The Formation of the English Kingdom in the Tenth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-871791-1.

- Oram, RD (2011) [2001]. The Kings & Queens of Scotland. Brimscombe Port: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7099-3.

- Parsons, DN (2011). "On the Origin of 'Hiberno-Norse Inversion-Compounds'" (PDF). The Journal of Scottish Name Studies. 5: 115–152. ISSN 2054-9385.

- Rhŷs, J; Evans, JG, eds. (1890). The Text of the Bruts From the Red Book of Hergest. Oxford. OL 19845420M.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Schrijver, P (1995). Studies in British Celtic Historical Phonology. Leiden Studies in Indo-European. Amsterdam: Rodopi. ISBN 90-5183-820-4.

- Smyth, AP (1989) [1984]. Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland, AD 80–1000. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0 7486 0100 7.

- Stenton, F (1963). Anglo-Saxon England. The Oxford History of England (2nd ed.). Oxford: The Clarendon Press. OL 24592559M.

- Stevenson, WH (1898). "The Great Commendation to King Edgar in 973". English Historical Review. 13 (51): 505–507. doi:10.1093/ehr/XIII.LI.505. eISSN 1477-4534. ISSN 0013-8266. JSTOR 547617.

- Thornton, DE (2001). "Edgar and the Eight Kings, AD 973: Textus et Dramatis Personae". Early Medieval Europe. 10 (1): 49–79. doi:10.1111/1468-0254.00079. eISSN 1468-0254. hdl:11693/24776.

- Todd, JM (2005). "British (Cumbric) Place-Names in the Barony of Gilsland, Cumbria" (PDF). Transactions of the Cumberland & Westmorland Antiquarian & Archaeological Society. 5: 89–102. doi:10.5284/1032950.

- Wadden, P (2015). "The Normans and the Irish Sea World in the Era of the Battle of Clontarf". In McAlister, V; Barry, T (eds.). Space and Settlement in Medieval Ireland. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 15–33. ISBN 978-1-84682-500-2.

- Walker, IW (2013) [2006]. Lords of Alba: The Making of Scotland (EPUB). Brimscombe Port: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-9519-4.

- Williams, A (1999). Kingship and Government in Pre-Conquest England, c.500–1066. British History in Perspective. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Macmillan Press. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-27454-3. ISBN 978-1-349-27454-3.

- Williams, A (2004a). "An Outing on the Dee: King Edgar at Chester, AD 973". Mediaeval Scandinavia. 14: 229–243.

- Williams, A (2004b). "Edmund I (920/21–946)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8501. Retrieved 9 July 2016. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Williams, A (January 2014). "Edgar (943/4–975)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8463. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) - Williams, A; Smyth, AP; Kirby, DP (1991). A Biographical Dictionary of Dark Age Britain: England, Scotland and Wales, c.500–c.1050. London: Seaby. ISBN 1-85264-047-2.

- Woolf, A (2007). From Pictland to Alba, 789–1070. The New Edinburgh History of Scotland. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1233-8.

- Woolf, A (2009). "Scotland". In Stafford, P (ed.). A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland, c.500–c.1100. Blackwell Companions to British History. Chichester: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 251–267. ISBN 978-1-405-10628-3.

- Woolf, A (2010). "Reporting Scotland in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle". In Jorgensen, A (ed.). Reading the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: Language, Literature, History. Studies in the Early Middle Ages. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. pp. 221–239. doi:10.1484/M.SEM-EB.3.4457. ISBN 978-2-503-52394-1.

External links

Media related to Máel Coluim mac Domnaill at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Máel Coluim mac Domnaill at Wikimedia Commons- Malcolm 4 at Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England