Gryposaurus

| Gryposaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| G. monumentensis skeleton in the Natural History Museum of Utah | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Neornithischia |

| Clade: | †Ornithopoda |

| Family: | †Hadrosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Saurolophinae |

| Tribe: | †Kritosaurini |

| Genus: | †Gryposaurus |

| Type species | |

| †Gryposaurus notabilis Lambe, 1914

| |

| Species | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Gryposaurus (meaning "hooked-nosed (Greek grypos) lizard";[1] sometimes incorrectly translated as "griffin (Latin gryphus) lizard"[2]) was a genus of duckbilled dinosaur that lived about 80 to 75 million years ago, in the Late Cretaceous (late Santonian to late Campanian stages) of North America. Named species of Gryposaurus are known from the Dinosaur Park Formation in Alberta, Canada, and two formations in the United States: the Lower Two Medicine Formation in Montana and the Kaiparowits Formation of Utah. A possible additional species may extend the temporal range of the genus to 66 million years ago.

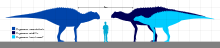

Gryposaurus is similar to Kritosaurus, and for many years the two were thought to be synonyms. It is known from numerous skulls, some skeletons, and even some skin impressions that show it to have had pyramidal scales projecting along the midline of the back. It is most easily distinguished from other duckbills by its narrow arching nasal hump, sometimes described as similar to a "Roman nose,"[1] and which may have been used for species or sexual identification, and/or combat with individuals of the same species. A large bipedal/quadrupedal herbivore around 9 meters (30 feet) long, it may have preferred river settings.

History of discovery

Gryposaurus is based on specimen NMC 2278, a skull and partial skeleton collected in 1913 by George F. Sternberg from what is now known as the Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, along the Red Deer River.[2] This specimen was described and named by Lawrence Lambe shortly thereafter, Lambe drawing attention to its unusual nasal crest.[3] A few years earlier, Barnum Brown had collected and described a partial skull from New Mexico, which he named Kritosaurus. This skull was missing the snout, which had eroded into fragments; Brown restored it after the duckbill now known as Anatotitan, which was flat-headed,[4] and believed that some unusual pieces were evidence of compression.[5] Lambe's description of Gryposaurus provided evidence of a different type of skull configuration, and by 1916 the Kritosaurus skull had been redone with a nasal arch and both Brown and Charles Gilmore had proposed that Gryposaurus and Kritosaurus were one and the same.[6][7] This idea was reflected in William Parks's naming of a nearly complete skeleton from the Dinosaur Park Formation as Kritosaurus incurvimanus, not Gryposaurus incurvimanus (although he left Gryposaurus notabilis in its own genus).[8] Direct comparison between Kritosaurus incurvimanus and Gryposaurus notabilis is hindered by the fact that the incurvimanus type specimen is missing the front part of the skull, so the full shape of the nasal arch cannot be seen. The 1942 publication of the influential Lull and Wright monograph on hadrosaurs sealed the Kritosaurus/Gryposaurus question for nearly fifty years in favor of Kritosaurus. Reviews beginning in the 1990s, however, called into question the identity of Kritosaurus navajovius, which has limited material for comparison with other duckbills.[9] Thus, Gryposaurus has once again been separated, at least temporarily, from Kritosaurus.

This situation is made more confusing by old suggestions by some authors, including Jack Horner, that Hadrosaurus is also the same as either Gryposaurus, Kritosaurus, or both.[10] This hypothesis was most common in the late 1970s–early 1980s, and appears in some popular books;[11][12] one well-known work, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs, uses Kritosaurus for the Canadian material (Gryposaurus), but identifies the mounted skeleton of K. incurvimanus as Hadrosaurus in a photo caption.[13] Although Horner in 1979 used the new combination Hadrosaurus [Kritosaurus] notabilis for a partial skull and skeleton and a second less-complete skeleton from the Bearpaw Shale of Montana[10] (which have since fallen out of the literature), by 1990 he had changed his position, and was among the first to again use Gryposaurus in print.[9] Current thought is that Hadrosaurus, although known from fragmentary material, can be distinguished from Gryposaurus by differences in the upper arm and ilium.[14]

Further research has revealed the presence of a second species, G. latidens, from slightly older rocks in Montana than the classic gryposaur localities of Alberta. Based on two parts of a skeleton collected in 1916 for the American Museum of Natural History,[15] G. latidens is also known from bonebed material. Horner, who described the specimens, considered it to be a less derived species.[16]

New material from the Kaiparowits Formation of Utah, in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, includes a skull and partial skeleton that represent the species G. monumentensis. Its skull was more robust than that of the other species, and its predentary had enlarged prongs along its upper margin, where the lower jaw's beak was based. This new species greatly expands the geographic range of this genus, and there may be a second, more lightly built species present as well.[17] Multiple gryposaur species are known from the Kaiparowits Formation, represented by cranial and postcranial remains, and were larger than their northern counterparts.[18]

Species

As of 2016, there are currently three named species that are recognized as valid today: G. notabilis, G. latidens, and G. monumentensis.[19] The type species G. notabilis is from the late Campanian-age Upper Cretaceous Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, Canada.[19] It is now thought that another species from the same formation, Kritosaurus incurvimanus (also known as Gryposaurus incurvimanus), is a synonym of G. notabilis.[19] The two had been differentiated by the size of the nasal arch (larger and closer to the eyes in G. notabilis) and the form of the upper arm (longer and more robust in K. incurvimanus).[16] Ten complete skulls and twelve fragmentary skulls are known for G. notabilis along with postcrania,[20] as well as with two skeletons with skulls that had been assigned to K. incurvimanus.[21] G. latidens, from the late Santonian-early Campanian Lower Two Medicine Formation of Pondera County, Montana, USA, is known from partial skulls and skeletons from several individuals. Its nasal arch is prominent like that of G. notabilis, but farther forward on the snout, and its teeth are less derived, reflecting iguanodont-like characteristics.[16] The informal name "Hadrosauravus"[22] is an early, unused name for this species.[23] G. monumentensis is known from a skull and partial skeleton from Utah.[17] G. monumentensis was listed second on the top 10 list of new species in 2008 by the International Institute for Species Exploration.[24] Recently, a possible fourth species of Gryposaurus, Gryposaurus alsatei, was unearthed in the Javelina Formation, which dates to the late Maastrichtian, along with an unnamed species of Kritosaurus and an undescribed saurolophine which closely resembles Saurolophus, but with a more solid crest.[25]

The dubious hadrosaurid Stephanosaurus marginatus[26] was considered a possible species of Kritosaurus, following the synonymy of Gryposaurus with Kritosaurus.[27][28][2] However, this synonymy was rejected in the 2004 edition of the Dinosauria, with Stephanosaurus being tabulated as dubious.[20]

Description

Gryposaurus was a hadrosaurid of typical size and shape; one of the best specimens of this genus, the nearly complete type specimen of Kritosaurus incurvimanus (now regarded as a synonym of Gryposaurus notabilis) came from an animal about 8.2 meters (27 feet) long.[29] This specimen also has the best example of skin impressions for Gryposaurus, showing this dinosaur to have had several different types of scalation: pyramidal, ridged, limpet-shaped scutes upwards of 3.8 centimeters long (1.5 inches) on the flank and tail; uniform polygonal scales on the neck and sides of the body; and pyramidal structures, flattened side-to-side, with fluted sides, longer than tall and found along the top of the back in a single midline row.[30]

The three named species of Gryposaurus differ in details of the skull and lower jaw.[2] The prominent nasal arch found in this genus is formed from the paired nasal bones. In profile view, they rise into a rounded hump in front of the eyes, reaching a height as tall as the highest point of the back of the skull.[3] The skeleton is known in great detail,[31] making it a useful point of reference for other duckbill skeletons.

Classification

Gryposaurus was a saurolophine (hadrosaurine of older references) hadrosaurid, a member of the duckbill subfamily without hollow head crests.[20] The general term "gryposaur" is sometimes used for duckbills with arched nasals.[9] Tethyshadros was once thought to fall into this group as well, before it was described (then known under the nickname "Antonio").[32] A subfamily, Gryposaurinae, was coined by Jack Horner as part of a larger revision that promoted Hadrosaurinae to family status,[16] but is not now in use. A rough equivalent is Kritosaurini, as used by Alberto Prieto-Márquez.[33] The main difference between the two is and age (Kritosaurus comes from slightly younger rocks than Gryposaurus). Otherwise, the skull of Kritosaurus is incompletely known, lacking most of the bones in front of the eyes, but very similar to that of Gryposaurus.[5]

The following is a cladogram based on the phylogenetic analysis conducted by Prieto-Márquez and Wagner in 2012, showing the relationships of Gryposaurus among the other kritosaurins:[33]

| Kritosaurini |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

As a hadrosaurid, Gryposaurus would have been a bipedal/quadrupedal herbivore, eating a variety of plants. Its skull had special joints that permitted a grinding motion analogous to chewing, and its teeth were continually replacing and packed into dental batteries that contained hundreds of teeth, only a relative handful of which were in use at any time. Plant material would have been cropped by its broad beak, and held in the jaws by a cheek-like organ. Its feeding range would have extended from the ground to about 4 m (13 ft) above.[20]

Like other bird-hipped dinosaurs of the Dinosaur Park Formation, Gryposaurus appears to have only existed for part of the duration of time that the rocks were being formed. As the formation was being laid down, it recorded a change to more marine-influenced conditions. Gryposaurus is absent from the upper part of the formation, with Prosaurolophus present instead. Other dinosaurs known from only the lower part of the formation include the horned Centrosaurus and the hollow-crested duckbill Corythosaurus.[21] Gryposaurus may have preferred river-related settings.[20]

Nasal arch

The distinctive nasal arch of Gryposaurus, like other cranial modifications in duckbills, may have been used for a variety of social functions, such as identification of sexes or species and social ranking.[20] It could also have functioned as a tool for broadside pushing or butting in social contests, and there may have been inflatable air sacs flanking it for both visual and auditory signaling.[34] The top of the arch is roughened in some specimens, suggesting that it was covered by thick, keratinized skin,[34] or that there was a cartilaginous extension.[16]

Paleoecology

Utah

Argon-argon radiometric dating indicates that the Kaiparowits Formation was deposited between 76.1 and 74.0 million years ago, during the Campanian stage of the Late Cretaceous period.[35][36] During the Late Cretaceous period, the site of the Kaiparowits Formation was located near the western shore of the Western Interior Seaway, a large inland sea that split North America into two landmasses, Laramidia to the west and Appalachia to the east. The plateau where dinosaurs lived was an ancient floodplain dominated by large channels and abundant wetland peat swamps, ponds and lakes, and was bordered by highlands. The climate was wet and humid, and supported an abundant and diverse range of organisms.[37] This formation contains one of the best and most continuous records of Late Cretaceous terrestrial life in the world.[38]

Gryposaurus monumentensis shared its paleoenvironment with other dinosaurs, such as dromaeosaurid theropods, the troodontid Talos sampsoni, ornithomimids like Ornithomimus velox, tyrannosaurids like Albertosaurus and Teratophoneus, armored ankylosaurids, the duckbilled hadrosaur Parasaurolophus cyrtocristatus, the ceratopsians Utahceratops gettyi, Nasutoceratops titusi and Kosmoceratops richardsoni and the oviraptorosaurian Hagryphus giganteus.[39] Other paleofauna present in the Kaiparowits Formation included chondrichthyans (sharks and rays), frogs, salamanders, turtles, lizards and crocodilians. A variety of early mammals were present including multituberculates, marsupials, and insectivorans.[40]

See also

References

- ^ a b Creisler, Benjamin S. (2007). "Deciphering duckbills". In Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.). Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 185–210. ISBN 978-0-253-34817-3.

- ^ a b c d Glut, Donald F. (1997). "Gryposaurus". Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. pp. 445–448. ISBN 978-0-89950-917-4.

- ^ a b Lambe, Lawrence M. (1914). "On Gryposaurus notabilis, a new genus and species of trachodont dinosaur from the Belly River Formation of Alberta, with a description of the skull of Chasmosaurus belli". The Ottawa Naturalist. 27 (11): 145–155.

- ^ Brown, Barnum (1910). "The Cretaceous Ojo Alamo beds of New Mexico with description of the new dinosaur genus Kritosaurus". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 28 (24): 267–274. hdl:2246/1398.

- ^ a b Kirkland, James I.; Hernández,-Rivera, René; Gates, Terry; Paul, Gregory S.; Nesbitt, Sterling; Serrano-Brañas, Claudia Inés; Garcia-de la Garza, Juan Pablo (2006). "Large hadrosaurine dinosaurs from the latest Campanian of Coahuila, Mexico". In Lucas, Spencer G.; Sullivan Robert M. (eds.). Late Cretaceous vertebrates from the Western Interior. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 35. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 299–315.

- ^ Brown, Barnum (1914). "Cretaceous Eocene correlation in New Mexico, Wyoming, Montana, Alberta" (PDF). Geological Society of America Bulletin. 25: 355–380. doi:10.1130/gsab-25-355.

- ^ Gilmore, Charles W. (1916). "Contributions to the geology and paleontology of San Juan County, New Mexico. 2. Vertebrate faunas of the Ojo Alamo, Kirtland and Fruitland Formations". United States Geological Survey Professional Paper. 98-Q: 279–302.

- ^ Parks, William A. (1919). "Preliminary description of a new species of trachodont dinosaur of the genus Kritosaurus, Kritosaurus incurvimanus". Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada, Series 3. 13 (4): 51–59.

- ^ a b c Weishampel, David B.; Horner, Jack R. (1990). "Hadrosauridae". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (1st ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 534–561. ISBN 978-0-520-06727-1.

- ^ a b Horner, John R. (1979). "Upper Cretaceous dinosaurs from the Bearpaw Shale (marine) of south-central Montana with a checklist of Upper Cretaceous dinosaur remains from marine sediments in North America". Journal of Paleontology. 53 (3): 566–577.

- ^ Glut, Donald F. (1982). The New Dinosaur Dictionary. Secaucus, NJ: Citadel Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-8065-0782-8.

- ^ Lambert, David; the Diagram Group (1983). A Field Guide to Dinosaurs. New York: Avon Books. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-380-83519-5.

- ^ Norman, David. B. (1985). "Hadrosaurids I". The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs: An Original and Compelling Insight into Life in the Dinosaur Kingdom. New York: Crescent Books. pp. 116–121. ISBN 978-0-517-46890-6.

- ^ Prieto-Márquez, Alberto; Weishampel, David B.; Horner, John R. (2006). "The dinosaur Hadrosaurus foulkii, from the Campanian of the East Coast of North America, with a reevaluation of the genus" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 51 (1): 77–98.

- ^ Lull, Richard Swann; Wright, Nelda E. (1942). Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America. Geological Society of America Special Paper 40. Geological Society of America. p. 21.

- ^ a b c d e Horner, John R. (1992). "Cranial morphology of Prosaurolophus (Ornithischia: Hadrosauridae) with descriptions of two new hadrosaurid species and an evaluation of hadrosaurid phylogenetic relationships". Museum of the Rockies Occasional Paper. 2: 1–119.

- ^ a b Gates, Terry A.; Sampson, Scott D. (2007). "A new species of Gryposaurus (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae) from the late Campanian Kaiparowits Formation, southern Utah, USA". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 151 (2): 351–376. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00349.x.

- ^ Gates, Terry; Sampson, Scott (2006). "A new species of Gryposaurus (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae) from the Upper Campanian Kaiparowits Formation of Utah". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (3, Suppl): 65A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2006.10010069.

- ^ a b c Prieto–Marquez, Alberto (2010). "The braincase and skull roof of Gryposaurus notabilis (Dinosauria, Hadrosauridae), with a taxonomic revision of the genus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (3): 838–854. doi:10.1080/02724631003762971.

- ^ a b c d e f Horner, John R.; Weishampel, David B.; Forster, Catherine A (2004). "Hadrosauridae". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 438–463. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- ^ a b Ryan, Michael J.; Evans, David C. (2005). "Ornithischian Dinosaurs". In Currie, Phillip J.; Koppelhus Eva (eds.). Dinosaur Provincial Park: A Spectacular Ancient Ecosystem Revealed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 312–348. ISBN 978-0-253-34595-0.

- ^ Lambert, David; the Diagram Group (1990). The Dinosaur Data Book. New York: Avon Books. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-380-75896-8.

- ^ Olshevsky, George (1999-11-16). "Re: What are these dinosaurs?". Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ^ "Scientists Announce Top 10 New Species; Issue SOS". International Institute for Species Exploration. Newswise. 2008-05-23. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ^ Lehman, Thomas M.; Wick, Steve L.; Wagner, Jonathan R. (1 July 2016). "Hadrosaurian dinosaurs from the Maastrichtian Javelina Formation, Big Bend National Park, Texas". Journal of Paleontology. 1 (2): 333–356. doi:10.1017/jpa.2016.48. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ^ Lambe, Lawrence M. (1902). "On Vertebrata of the mid-Cretaceous of the Northwest Territory. 2. New genera and species from the Belly River Series (mid-Cretaceous)". Contributions to Canadian Paleontology. 3: 25–81.

- ^ Gilmore, Charles W. (1924). "On the genus Stephanosaurus, with a description of the type specimen of Lambeosaurus lambei, Parks". Canada Department of Mines Geological Survey Bulletin (Geological Series). 38 (43): 29–48.

- ^ Lull, Richard Swann; Wright, Nelda E. (1942). Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America. Geological Society of America Special Paper 40. Geological Society of America. pp. 164–172.

- ^ Lull, Richard Swann; Wright, Nelda E. (1942). Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America. Geological Society of America Special Paper 40. Geological Society of America. p. 226.

- ^ Lull, Richard Swann; Wright, Nelda E. (1942). Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America. Geological Society of America Special Paper 40. Geological Society of America. pp. 110–117.

- ^ Parks, William A. (1920). "The osteology of the trachodont dinosaur Kritosaurus incurvimanus". University of Toronto Studies, Geology Series. 11: 1–76.

- ^ Glut, Donald F. (2002). Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. Vol. Supplement 2. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-0-89950-917-4.

- ^ a b Prieto-Márquez, A.; Wagner, J.R. (2012). "Saurolophus morrisi, a new species of hadrosaurid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of the Pacific coast of North America" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. in press. doi:10.4202/app.2011.0049.

- ^ a b Hopson, James A. (1975). "The evolution of cranial display structures in hadrosaurian dinosaurs". Paleobiology. 1 (1): 21–43. doi:10.1017/S0094837300002165.

- ^ Roberts EM, Deino AL, Chan MA (2005) 40Ar/39Ar age of the Kaiparowits Formation, southern Utah, and correlation of contemporaneous Campanian strata and vertebrate faunas along the margin of the Western Interior Basin. Cretaceous Research 26: 307–318.

- ^ Eaton, J.G., 2002. Multituberculate mammals from the Wahweap(Campanian, Aquilan) and Kaiparowits (Campanian, Judithian) formations, within and near Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, southern Utah. Miscellaneous Publication 02-4, Utah Geological Survey, 66 pp.

- ^ Titus, Alan L. and Mark A. Loewen (editors). At the Top of the Grand Staircase: The Late Cretaceous of Southern Utah. 2013. Indiana University Press. Hardbound: 634 pp.

- ^ Clinton, William. "Preisdential Proclamation: Establishment of the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument". September 18, 1996. Archived from the original on 28 August 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ Zanno, Lindsay E.; Sampson, Scott D. (2005). "A new oviraptorosaur (Theropoda; Maniraptora) from the Late Cretaceous (Campanian) of Utah". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (4): 897–904. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0897:ANOTMF]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Eaton, Jeffrey G.; Cifelli, Richard L.; Hutchinson, J. Howard; Kirkland, James I.; Parrish, J. Michael (1999). "Cretaceous vertebrate faunas from the Kaiparowits Plateau, south-central Utah". In Gillete David D. (ed.). Vertebrate Paleontology in Utah. Miscellaneous Publication 99-1. Salt Lake City: Utah Geological Survey. pp. 345–353. ISBN 978-1-55791-634-1.