James McCormack

James McCormack | |

|---|---|

Brigadier General James McCormack, Jr, (right) is congratulated by Major General Lauris Norstad (left) after being presented with the oak leaf cluster to his Legion of Merit | |

| Born | 8 November 1910 Chatham, Louisiana |

| Died | 3 January 1975 (aged 64) Hilton Head Island, South Carolina |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1932–1955 |

| Rank | |

| Battles / wars | World War II |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Medal Legion of Merit (2) Bronze Star Commander of the Order of the British Empire (United Kingdom) Chevalier of the Legion of Honor (France) Croix de guerre 1939–1945 with silver star (France) |

| Other work | Director of Military Applications, Atomic Energy Commission Vice President for research at MIT Chairman of the Communications Satellite Corporation |

James McCormack, Jr. (8 November 1910 – 3 January 1975) was a United States Army officer who served in World War II, and was later the first Director of Military Applications of the United States Atomic Energy Commission.

A 1932 graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, McCormack also studied at Hertford College, Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar, and at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he earned a Master of Science degree in civil engineering. In 1942, he was assigned to the War Department General Staff. On 1 July 1944, he became the Chief of the Movements Branch of Twelfth United States Army Group, remaining in this role until 28 May 1945. He then returned to the War Department General Staff, where he served in the Operations and Plans Division.

In 1947 McCormack was chosen as the Director of Military Applications of the United States Atomic Energy Commission with the rank of brigadier general. He took a pragmatic approach to handling the issue of the proper agency to hold custody of the nuclear weapons stockpile, and encouraged and supported Edward Teller's development of thermonuclear weapons. He transferred to the United States Air Force on 25 July 1950, and was appointed Director of Nuclear Applications at the Air Research and Development Center in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1952. He was subsequently promoted to major general, and became Deputy Commander of the Air Research and Development Command.

After retiring from the Air Force in 1955, McCormack became the first head of the Institute for Defense Analysis, a non-profit research organization created to provide advice and support to the Department of Defense's scientific and technological research efforts formed by ten universities. In 1958 he became vice president for industrial and governmental relations at MIT, in which capacity he originated the proposal that the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics be used as the basis for a new space agency, which eventually became the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. He was Chairman of the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, and from 1965 to 1970 was chairman of the Communications Satellite Corporation.

Early life and career

James McCormack, Jr., was born in Chatham, Louisiana, on 8 November 1910. He attended the Riverside Military Academy in Gainesville, Georgia,[1] before entering the United States Military Academy at West Point on 2 July 1928. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the United States Army Corps of Engineers on graduation on 14 August 1932, ranking 19th in his class. He departed for England where he studied at Hertford College, Oxford, as a Rhodes Scholar. He was promoted to first lieutenant in August 1935, and awarded his Bachelor of Arts degree from Oxford. On returning to the United States, he was posted to the 8th Engineers at Fort McIntosh, Texas, as a troop commander.[2][3]

In June 1936 he became a student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, from which he graduated with a Master of Science degree in civil engineering in August 1937. He then became a student officer at the Engineering School at Fort Belvoir, Virginia. In June 1938, he reported to Vicksburg, Mississippi, as Assistant Project Engineer on the Sardis Reservoir Project.[2][3]

World War II

McCormack reported to Fort Benning, Georgia, as a company commander in the 21st Engineers in October 1939.[1] He was promoted to captain on 9 September 1940, and after serving as adjutant of the 20th Engineers at Fort Benning, he temporarily commanded one of the regiment's battalions before assuming command of the 76th Engineer Company at Fort McClellan, Alabama, in mid-1941.[1] Later that year he attended the United States Army Command and General Staff College,[2] after which he was promoted to major on 1 February 1942, and posted to the War Department General Staff. He was Assistant Chief of the Types and Allowances Branch of G-4 from March 1942 to March 1943, with a promotion to lieutenant colonel on 9 October 1942, and then Chief of the Construction Branch of G-4 from March 1943 to September 1943.[3]

In October 1943, McCormack became Chief of the Transportation Branch of the First United States Army Group, and was promoted to colonel on 1 December 1943. On 1 July 1944, he became the Chief of the Movements Branch of Twelfth United States Army Group, remaining in this role until 28 May 1945. For his services in the European Theater of Operations, he was awarded the Legion of Merit on 30 December 1944, and the Bronze Star Medal in May 1945. The British government made him an honorary Commander of the Order of the British Empire on 24 March 1945, while the French government awarded him the Croix de guerre with the silver star on 29 January 1945, and made him a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor on 3 October 1945.[3]

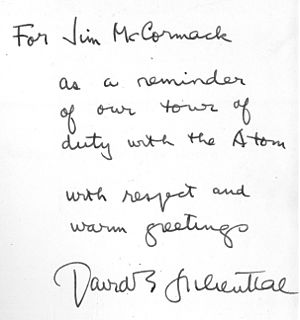

On 4 June 1945, McCormack returned to duty with the War Department General Staff as a member of the Policy Section of the Strategy and Policy Group, becoming the assistant section chief on 16 September 1945. He was then a staff officer with the Strategy and Policy Group from 16 February until 16 August 1946, when he became chief of the Politico-Military Survey Section of the Operations and Plans Division. For his service with the War Department General Staff, he was awarded an oak leaf cluster to his Legion of Merit on 8 April 1947.[3]

Cold War

At this point, McCormack had become apprehensive about his career, but in early 1947 a new and exciting opportunity opened up.[4] The Atomic Energy Act of 1946 had created the United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) to oversee research and development of nuclear power and nuclear weapons. The Act had created a statutory position inside the AEC called the Director of Military Applications, which the AEC commissioners envisaged as a staff post responsible for military planning and policy formulation. By law, the Director of Military Applications had to be a serving armed forces officer.[5]

The frontrunner for the post was the wartime commander of the Manhattan District, Brigadier General Kenneth Nichols. Indeed, Nichols was the War Department's only nominee. However, the AEC commissioners had different ideas. Nichols was seen as too closely identified with the wartime Manhattan Project; he had opinions at variance with the commissioners on whether the Director of Military Applications was a staff or a line position; and he had a strong disagreement with the commissioners over the vexing issue of which agency should hold custody of the nuclear weapons stockpile. Accordingly, the AEC commissioners decided to find another candidate.[5][6]

The AEC commissioners asked for Major General Lauris Norstad, the head of the Operations and Plans Division, but neither the Chief of Staff of the Army, General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower, nor the Secretary of War, Robert P. Patterson, was willing to release him. The commissioners then selected McCormack. The job came with a promotion to brigadier general.[4][1] The commissioners got the kind of officer that they wanted. McCormack was willing to accept the post as a staff job, and took a pragmatic approach to the custody issue. Like most military officers, he was convinced that the men who had to use the nuclear weapons in battle needed to have experience in their proper maintenance, storage and handling. However, he was also aware of the sensitivity of the issue of custody, which Congress had assigned to the AEC. Rather than continue to press for changes in the law, he accepted the situation as it was, and strove to make the best of it, working within the existing framework.[7]

McCormack became involved in discussions with Edward Teller over the possibility of developing thermonuclear weapons, then known as the "Super".[8] McCormack became an early advocate of the Super, which promised yields in the megaton range, and directed Norris Bradbury at the Los Alamos National Laboratory to proceed with its development even at the detriment of other weapons.[9] The debate over the merits of the Super pitted the United States Air Force against the other services, which wanted more small, tactical weapons. Concurrently, there was a technical debate between Teller and other scientists like Robert Oppenheimer over the feasibility of the Super, because there was no guarantee that it would work, and even after Operation Greenhouse, the processes involved in thermonuclear reactions were not fully understood. It ultimately became apparent that the Super design would not work,[10] but the development of the Teller-Ulam design provided a new path to high yield thermonuclear weapons.[11] For his services as Director of Military Applications, McCormack was awarded the Army Distinguished Service Medal.[3]

Later life

McCormack transferred to the United States Air Force on 25 July 1950. After leaving the AEC in August 1951, he became Special Assistant to the Deputy Chief of Staff of the Air Force for Development. In January 1952 he was appointed Director of Nuclear Applications at the Air Research and Development Center in Baltimore, Maryland.[3] He was subsequently promoted to major general, and became Deputy Commander of the Air Research and Development Command. He was called to testify at the Oppenheimer security hearing. Like other witnesses, McCormack testified that Oppenheimer was loyal,[12] and that while the two men had disagreed over the merits of the Super, that he saw nothing dishonest or disloyal in Oppenheimer's opposition to it.[13]

McCormack retired from the Air Force in 1955, and became the first head of the Institute for Defense Analysis, a non-profit research organization to provide advice and support to the Department of Defense's scientific and technological research efforts formed by ten universities.[14] In 1958 he became vice president for industrial and governmental relations at MIT.[15][16] He originated the proposal that the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics be used as the basis for a new space agency, which eventually became the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.[17]

In 1964, the Governor of Massachusetts, Endicott Peabody, appointed McCormack as Chairman of the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority.[18] In October 1965, he was appointed chairman of the Communications Satellite Corporation (COMSAT),[19] with a $125,000 salary. To allow himself to concentrate on his new position, he resigned all his company directorships, along with his post at MIT. He attended his first board meeting in Washington, DC, in his dinner jacket, having flown from Los Angeles after a speaking engagement. As head of a quasi-government organization, McCormack strove to employ the company's resources to carry out the policies of Congress and the President, and was able to persuade Congress to declassify plans for a domestic satellite network so he could consult with the television networks. He retired as chairman due to ill health in 1970, although he remained a director.[14]

McCormack died at his winter home in Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, on 3 January 1975, and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. He was survived by his wife, Eleanor née Morrow; his son, Major James R. McCormack, who was stationed at Fort Rucker, Alabama; and his daughter, Anne M. Stanton, who was living at Fort Campbell, Kentucky.[14]

Notes

- ^ a b c d "Biographies: Major General James McCormack Jr". Official US Air Force website. US Government. Archived from the original on 2 August 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ^ a b c Cullum 1940, p. 939.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fogerty 1953.

- ^ a b Hewlett & Duncan 1969, p. 33.

- ^ a b Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 648–650.

- ^ Brahmstedt 2002, pp. 27–29.

- ^ Hewlett & Duncan 1969, pp. 136–138.

- ^ Hewlett & Duncan 1969, p. 369.

- ^ Hewlett & Duncan 1969, pp. 408–409, 414–415.

- ^ Hewlett & Duncan 1969, pp. 438–441, 535.

- ^ Hewlett & Duncan 1969, pp. 536–537.

- ^ Garrison, Lloyd K. (June 1954). "Oppenheimer Requests Review". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ Polenberg 2002, pp. 228–229.

- ^ a b c "Maj. Gen. James McCormack, Former Head of Comsat, Dead". The New York Times. Anne Arbor, Michigan. January 1975. p. 77.

- ^ Shrader 2006, p. 183.

- ^ Light 2003, p. 218.

- ^ "Journal of the British Interplanetary Society" (PDF). 32. 1979: 449–451. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Hanron, Robert B. (2 July 1964). "Gen McCormack To Run MBTA". The Boston Globe. p. 3.

- ^ Smith, Gend (16 October 1965). "Comsat Names a New Chairman; James McCormack, a Retired Air Force General, Is Chosen". The New York Times. p. 30. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

References

- Brahmstedt, Christian (2002). Defense's Nuclear Agency, 1947–1997 (PDF). DTRA history series. Washington, DC: Defense Threat Reduction Agency. OCLC 52137321. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cullum, George W. (1940). Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the US Military Academy at West Point New York Since Its Establishment in 1802: Supplement Volume VIII 1930–1940. Chicago: R. R. Donnelly and Sons, The Lakeside Press. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fogerty, Dr Robert O. (1953). Biographical data on Air Force General Officers (PDF). Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama: Air University. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hewlett, Richard G.; Anderson, Oscar E. (1962). The New World, 1939–1946. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-520-07186-7. OCLC 637004643.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hewlett, Richard G.; Duncan, Francis (1969). Atomic Shield, 1947–1952. A History of the United States Atomic Energy Commission. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-520-07187-5. OCLC 3717478.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Light, Jennifer S. (2003). From Warfare To Welfare: Defense Intellectuals and Urban Problems in Cold War America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7422-X. OCLC 51924188.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Polenberg, Richard (2002). In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer: The Security Clearance Hearing. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University. ISBN 0-8014-3783-0. OCLC 47767155.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shrader, Charles R. (2006). Atomic Shield, 1947–1952. History of Operations Research in the United States Army. Washington, D.C.: Office of the Deputy Under Secretary of the Army for Operations Research, U.S. Army. ISBN 0-16-072961-0. OCLC 73821793.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- 1910 births

- 1975 deaths

- American army personnel of World War II

- American Rhodes Scholars

- Chevaliers of the Légion d'honneur

- Honorary Commanders of the Order of the British Empire

- Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority people

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology alumni

- Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army)

- Recipients of the Legion of Merit

- People from Jackson Parish, Louisiana

- United States Military Academy alumni

- United States Air Force generals

- United States Army generals

- United States Army Command and General Staff College alumni

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery