Brodifacoum

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

3-[3-[4-(4-Bromophenyl)phenyl]-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalen-1-yl]-2-hydroxychromen-4-one

| |

| Other names

Bromfenacoum

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.054.509 |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C31H23BrO3 | |

| Molar mass | 523.426 g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | 228 to 230 °C (442 to 446 °F; 501 to 503 K) |

| Insoluble | |

| Pharmacology | |

| Oral; dermal; inhalation (dusts) (for poisoning) | |

| Pharmacokinetics: | |

| 100% | |

| slow, incomplete, hepatic | |

| Slow; 20—130 days | |

| faeces; very slow | |

| Hazards | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

270 μg/kg (rat, oral)[inconsistent] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Brodifacoum is a highly lethal 4-hydroxycoumarin vitamin K antagonist anticoagulant poison. In recent years, it has become one of the world's most widely used pesticides. It is typically used as a rodenticide, but is also used to control larger pests such as possum.[2]

Brodifacoum has an especially long half-life in the body, which ranges up to nine months, requiring prolonged treatment with antidotal vitamin K for both human and pet poisonings. It has one of the highest risks of secondary poisoning to both mammals and birds.[3] Significant experience in brodifacoum poisonings has been gained in many human cases where it has been used in attempted suicides, necessitating long periods of vitamin K treatment. In March 2018, cases of severe coagulopathy and bleeding associated with synthetic cannabinoid use contaminated with brodifacoum were reported in five states of the US.

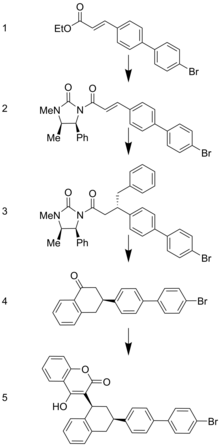

Chemical synthesis

Brodifacoum is a derivative of the 4-hydroxy-coumarin group. Compound 1 is the starting ester needed to synthesize brodifacoum. To obtain this starting compound, a simple Wittig condensation of ethyl chloroacetate with 4’-bromobiphenylcarboxaldehyde is accomplished. Compound 1 is transformed into 2 by consecutive hydrolysis, halogenation to form an acid chloride, and then reacted with the required lithium anion. This is done using KOH and EtOH for hydrolysis, and then adding SOCl2 for chlorination to form the acid chloride which reacts with the addition of lithium anion. Compound 2 is then transformed using organocopper chemistry to yield compound 3 with good stereoselectivity of about 98%. Typically, a Friedel-Crafts type cyclization would then be used to obtain the two-ring system portion of compound 4, but this results in low yield. Instead, trifluoromethanesulfonic acid in dry benzene catalyzes the cyclization with good yield. The ketone is then reduced with sodium borohydride yielding a benzyl alcohol. Condensation with 4-hydroxycoumarin under HCl yields compound 5, brodifacoum.[4]

Toxicology

Brodifacoum is a 4-hydroxycoumarin anticoagulant, with a similar mode of action to its historical predecessors dicoumarol and warfarin. However, due to very high potency and long duration of action (elimination half-life of 20 – 130 days), it is characterised as a "second-generation" or "superwarfarin" anticoagulant.[5]

Brodifacoum inhibits the enzyme vitamin K epoxide reductase, which is needed for the reconstitution of the vitamin K in its cycle from vitamin K-epoxide, so brodifacoum steadily decreases the level of active vitamin K in the blood. Vitamin K is required for the synthesis of important substances including prothrombin, which is involved in blood clotting. This disruption becomes increasingly severe until the blood effectively loses any ability to clot.

In addition, brodifacoum (as with other anticoagulants in toxic doses) increases permeability of blood capillaries; the blood plasma and blood itself begin to leak from the smallest blood vessels. A poisoned animal suffers progressively worsening internal bleeding, leading to shock, loss of consciousness, and eventually death.[citation needed]

Brodifacoum is highly lethal to mammals and birds, and extremely lethal to fish. It is a highly cumulative poison, due to its high lipophilicity and extremely slow elimination.[citation needed]

Following are acute LD50 values for a variety of animals:

| * rats (oral) | 0.27 mg/kg b.w.[6] |

| * mice (oral) | 0.40 mg/kg b.w.[6] |

| * rabbits (oral) | 0.30 mg/kg b.w.[6] |

| * guinea-pigs (oral) | 0.28 mg/kg b.w.[6] |

| * squirrels (oral) | 0.13 mg/kg b.w.[7] |

| * cats (oral)[8] | 0.25 mg/kg b.w.[9][6] — 25 mg/kg b.w.[10][11][12][13][6][14] |

| * dogs (oral) | 0.25 — 3.6 mg/kg b.w.[6][9][10][11][12][13] |

| * birds | LD50 values for various birds vary from about 1 mg/kg b.w. — 20 mg/kg b.w.[5] |

| * fish — LC50 for fish: | |

| ** trout (96 hours exposure) | 0.04 ppm[15] |

Brand names

Brodifacoum is marketed under many trade names, including Biosnap, d-CON, Finale, Fologorat, Havoc, Jaguar, Klerat, Matikus, Mouser, Pestoff, Rakan, Ratak+, Rataquill Colombia, Ratshot Red, Rattex, Rodend, Rodenthor, Ratsak, Talon, Volak, Vertox, and Volid.

Human poisoning

Treatment

The primary antidote to brodifacoum poisoning is immediate administration of vitamin K1 (dosage for humans: initially slow intravenous injections of 10–25 mg repeated at 3–6 hours until normalisation of the prothrombin time; then 10 mg orally four times daily as a "maintenance dose"). It is an extremely effective antidote, provided the poisoning is caught before excessive bleeding ensues. As high doses of brodifacoum can affect the body for many months, the antidote must be administered regularly for a long period (several months, in keeping with the substance's half-life) with frequent monitoring of the prothrombin time.[16]

If unabsorbed poison is still in the digestive system, gastric lavage followed by administration of activated charcoal may be required.

Further treatments to be considered include infusion of blood or plasma to counteract hypovolemic shock, and in severe cases, infusion of blood clotting factor concentrate.

Case reports

Cases of brodifacoum intoxication have been reported in the human medical literature.

In one report, a woman deliberately consumed over 1.5 kg of rat bait, constituting about 75 mg brodifacoum, but made a full recovery after receiving conventional medical treatment.[17]

In another case reported in 2013, a 48-year-old female patient reported 4 days of mild dyspnea, dry cough, bilateral popliteal fossae pain, and diffuse upper abdominal pain. She had no history of liver disease or alcohol or illicit substance abuse. Initial physical examination was remarkable only for mildly pale conjunctivae and mild abdominal tenderness and pain in the left popliteal fossa. A complete blood count and complete metabolic panel were normal. Prothrombin time (PT) was above 100 s, partial thromboplastin time (PTT) was above 200 s and international normalized ratio (INR) was reported as above 12.0. Urinalysis revealed hematuria (blood in the urine). Venous Doppler ultrasound of lower extremities demonstrated left popliteal vein thrombosis. Computed tomography scan of the abdomen demonstrated transmural hematoma, and a fecal occult blood test was positive. A full anticoagulant work-up showed critical reduction of vitamin K-dependent factors II, VII, IX, and X. PT and PTT corrected with mixing studies proving factor deficiency as the cause of the coagulopathy. Lupus anticoagulant studies were negative. Superwarfarin toxicity was suspected and confirmed with an anticoagulant poison panel positive for brodifacoum. The patient was hospitalized and successfully treated with fresh frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate, and vitamin K. In conclusion, paradoxical thrombosis and hemorrhage should raise the suspicion for superwarfarin toxicity in the appropriate clinical setting. Concomitant presentation for thrombosis and hemorrhage with remarkably abnormal PT and PTT should raise the suspicion for brodifacoum poisoning.[18]

In another report, a 17-year-old boy presented to the hospital with a severe bleeding disorder. He was found to have habitually smoked a mixture of brodifacoum and marijuana. Despite treatment with vitamin K, the bleeding disorder persisted for several months. He eventually recovered.[19]

In 2015, 19 inmates in New York City's Rikers Island jail claimed that they had been poisoned with the chemical. The inmates had noticed "what appeared to be blue and green pellets in the meatloaf" they were eating on March 3, and felt ill afterwards. A sample was analyzed and tested positive for brodifacoum; the NYC Department of Corrections stated it was investigating the incident.[20][21]

A 20-year-old female college student presented with abdominal pain and blood in urine. She was tested for warfarin, a common anticoagulant also used in some rodenticides, which returned a negative result. Vitamin K and fresh plasma were administered to treat symptoms. Three weeks later, she returned with bleeding into her calf, and was subsequently tested for superwarfarin chemicals. The test showed that brodifacoum was in her bloodstream. She later admitted to consuming seven packets of rodenticide.[22]

A 48-year-old businessman was admitted with a severe nosebleed and abnormal coagulation parameters. Standard treatment of vitamin K and fresh plasma was administered to stem the nosebleed. Two weeks later, he presented again with bleeding into the calf. Continual doses of vitamin K were necessary to counteract the brodifacoum. He denied taking any of the brodifacoum found in his home contained within packages of Contrac.[22]

As of November 26, 2018, at least eight fatalities and 320 cases of severe coagulopathy and bleeding associated with synthetic cannabinoid use had been reported in Illinois, Wisconsin, Maryland, Missouri, Florida, North Carolina, Indiana, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia.[23][24][25] The first case occurred in Illinois on March 7, 2018. [26] Brodifacoum was suspected to be present in these products in Illinois. Products named Matrix and Blue Giant from a convenience store in Chicago have tested positive for brodifacoum and AMB-FUBINACA (FUB-AMB).[27][28][29]

References

- ^ Merck Index, 11th Edition, 1368

- ^ Eason, C.T. and Wickstrom, M. Vertebrate pesticide toxicology manual, New Zealand Department of Conservation

- ^ Rodenticides: Topic Fact Sheet, National Pesticide Information Center

- ^ van Heerden P. S.; Bezuidenhoudt B. C. (1997), "Efficient Asymmetric Synthesis of the Four Diastereomers of Diphenacoum and Brodifacoum", Tetrahedron, 43 (17): 6045–6056, doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(97)00254-8

- ^ a b "Brodifacoum (HSG 93, 1995)". Inchem.org. Retrieved 2013-12-08.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Brodifacoum (PDS)". Inchem.org. Archived from the original on 2013-12-13. Retrieved 2017-12-05.

- ^ Matschke, George H.; Baril, Steve F; Blaskiewicz, Raymond W. (December 1983). "Population Reduction of Richardson's Ground Squirrels Using a Brodifacoum Bait". Great Plains Wildlife Damage Control Workshop Proceedings --- University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

- ^ Published LD50 values of brodifacoum for cats vary widely, from 25 mg kg-1(Rammell et al., 1984;Godfrey, 1985) to 0.25 mg kg-1(Haydock and Eason, 1997)

- ^ a b Brodifacoum at InChem.com

- ^ a b KAUKEINEN, D.E. 1979. Experimental rodenticide (Talon) passes lab tests; moving to field trials in pest control industry. Pest Control 46(1):19-21.

- ^ a b Brodifacoum (Talon, Havoc) - Chemical Profile 1/85

- ^ a b "MSDS Data Sheet for TALON RAT AND MOUSE KILLER" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-09-14. Retrieved 2010-07-06.

- ^ a b "The Veterinarian's Guide to accidental rodenticideingestion by dogs & cats" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-07-09. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- ^ Brodifacoum residues in target and non-target species following an aerial poisoning operation on Motuihe Island, Hauraki Gulf, NEW ZEALAND Pdf

- ^ "Pest Control Product Labels And MSDS" (PDF). Wil-kil.com. Retrieved 2013-12-08.

- ^ Olmos V, López CM (2007). "Brodifacoum poisoning with toxicokinetic data". Clin Toxicol. 45 (5): 487–9. doi:10.1080/15563650701354093. PMID 17503253.

- ^ Lipton R.A.; Klass E.M. (1984). "Human ingestion of a 'superwarfarin' rodenticide resulting in a prolonged anticoagulant effect". JAMA. 252 (21): 3004–3005. doi:10.1001/jama.252.21.3004.

- ^ Franco, David; Everett, George; Manoucheri, Manoucher (2013). "I smell a rat". Blood Coagulation & Fibrinolysis. 24 (2): 202–4. doi:10.1097/mbc.0b013e328358e959. PMID 23358203.

- ^ La Rosa F; Clarke S; Lefkowitz J. B. (1997). "Brodifacoum intoxication with marijuana smoking". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 121: 67–69.

- ^ Marzulli, John. "EXCLUSIVE: Rikers Island meatloaf that left 19 inmates sick did have rat poison, lab tests confirm". New York Daily News. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ Sydney Lupkin, "22 Rikers Island Prisoners Sickened By Rat Poison in Meatloaf, Lawyer Says, Daily News April 29, 2015

- ^ a b Weitzel, J. N. (1990), "Surreptitious Ingestion of a Long-Acting Vitamin K Antagonist/Rodenticide, Brodifacoum: Clinical and Metabolic Studies of Three Cases", Blood, 76 (12): 2555–2559, doi:10.1182/blood.V76.12.2555.2555

- ^ "COCA Clinical Action: Outbreak Alert Update: Potential Life-Threatening Vitamin K-Dependent Antagonist Coagulopathy Associated With Synthetic Cannabinoids Use". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2018-11-26.

- ^ McCoppin, Robert. "Illinois gets donation of nearly 800,000 vitamin K tablets to treat poisoning from synthetic marijuana". chicagotribune.com.

- ^ "Synthetic Marijuana Expands to Florida - Florida Department of Health in Hillsborough". hillsborough.floridahealth.gov.

- ^ Center for Acute Disease Epidemiology, Iowa Department of Public Health Coagulopathies Associated with Contaminated Synthetic Cannabinoids April 6, 2018

- ^ CNN, Jacqueline Howard and Marlena Baldacci. "Fake weed leaves two dead, 54 with severe bleeding". CNN.

{{cite news}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ^ "3 arrested in Chicago in connection to synthetic pot; 2 deaths, 54 others cases of severe bleeding". WGN-TV. 2 April 2018.

- ^ "Masoud et al complaint - Department of Justice". www.justice.gov.

Further reading

- Tasheva, M. (1995). Environmental Health Criteria 175: Anticoagulant rodenticides. World Health Organisation: Geneva.

- Cabot Richard C (2007). "Case Records of the Massachusetts General Hospital (a near fatal case of brodifacoum poisoning)". New England Journal of Medicine. 356 (2): 174–182. doi:10.1056/NEJMcpc069032. PMID 17215536.

- Bell, Cathy (July 15, 2015). "Raptors and Rat Poison". Living Bird Magazine. Retrieved November 20, 2015.