Hydroxylamine

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Hydroxylamine (only preselected[1]) | |||

| Other names

Azinous acid

Aminol Azanol Hydroxyamine Hydroxyazane Hydroxylazane Nitrinous acid | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| 3DMet | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.029.327 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| 478 | |||

| KEGG | |||

| MeSH | Hydroxylamine | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| H3NO | |||

| Molar mass | 33.030 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Vivid white, opaque crystals | ||

| Density | 1.21 g cm−3 (at 20 °C)[2] | ||

| Melting point | 33 °C (91 °F; 306 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 58 °C (136 °F; 331 K) /22 mm Hg (decomposes) | ||

| log P | −0.758 | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 6.03 (NH3OH+) | ||

| Basicity (pKb) | 7.97 | ||

| Structure | |||

| Trigonal at N | |||

| Tetrahedral at N | |||

| 0.67553 D | |||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Heat capacity (C)

|

46.47 J K−1 mol−1 | ||

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

236.18 J K−1 mol−1 | ||

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−39.9 kJ mol−1 | ||

| Hazards | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | 129 °C (264 °F; 402 K) | ||

| 265 °C (509 °F; 538 K) | |||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose)

|

408 mg/kg (oral, mouse); 59–70 mg/kg (intraperitoneal mouse, rat); 29 mg/kg (subcutaneous, rat)[3] | ||

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | ICSC 0661 | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related hydroxylammonium salts

|

Hydroxylammonium chloride Hydroxylammonium nitrate Hydroxylammonium sulfate | ||

Related compounds

|

Ammonia | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Hydroxylamine is an inorganic compound with the formula NH2OH. The pure material is a white, unstable crystalline, hygroscopic compound.[4] However, hydroxylamine is almost always provided and used as an aqueous solution. It is used to prepare oximes, an important functional group. It is also an intermediate in biological nitrification. In biological nitrification, the oxidation of NH3 to hydroxylamine is mediated by the enzyme ammonia monooxygenase (AMO).[5] Hydroxylamine oxidoreductase (HAO) further oxidizes hydroxylamine to nitrite.[6]

History

Hydroxylamine was first prepared as hydroxylamine hydrochloride in 1865 by the German chemist Wilhelm Clemens Lossen (1838-1906); he reacted tin and hydrochloric acid in the presence of ethyl nitrate.[7] It was first prepared in pure form in 1891 by the Dutch chemist Lobry de Bruyn and by the French chemist Léon Maurice Crismer (1858-1944).[8][9]

Production

NH2OH can be produced via several routes. The main route is via the Raschig process: aqueous ammonium nitrite is reduced by HSO3− and SO2 at 0 °C to yield a hydroxylamido-N,N-disulfonate anion:

- NH

4NO

2 + 2 SO

2 + NH

3 + H

2O → 2 NH+

4 + N(OH)(SO

3)2−

2

This anion is then hydrolyzed to give (NH

3OH)

2SO

4:

- N(OH)(SO

3)2−

2 + H

2O → NH(OH)(SO

3)−

+ HSO−

4 - 2 NH(OH)(SO

3)−

+ 2 H

2O → (NH

3OH)

2SO

4 + SO4−

4

Solid NH2OH can be collected by treatment with liquid ammonia. Ammonium sulfate, (NH

4)

2SO

4, a side-product insoluble in liquid ammonia, is removed by filtration; the liquid ammonia is evaporated to give the desired product.[4]

The net reaction is:

- 2NO−

2 + 4SO

2 + 6H

2O + 6NH

3 → 4SO2−

4 + 6NH+

4 + 2NH

2OH

Hydroxylammonium salts can then be converted to hydroxylamine by neutralization:

- (NH3OH)Cl + NaOBu → NH2OH + NaCl + BuOH[4]

Julius Tafel discovered that hydroxylamine hydrochloride or sulfate salts can be produced by electrolytic reduction of nitric acid with HCl or H2SO4 respectively:[10][11]

- HNO

3 + 3 H

2 → NH

2OH + 2 H

2O

Hydroxylamine can also be produced by the reduction of nitrous acid or potassium nitrite with bisulfite:

- HNO

2 + 2 HSO−

3 → N(OH)(OSO

2)2−

2 + H

2O → NH(OH)(OSO

2)−

+ HSO−

4 - NH(OH)(OSO

2)−

+ H

3O+

(100 °C/1 h) → NH

3(OH)+

+ HSO−

4

Reactions

Hydroxylamine reacts with electrophiles, such as alkylating agents, which can attach to either the oxygen or the nitrogen atoms:

- R-X + NH2OH → R-ONH2 + HX

- R-X + NH2OH → R-NHOH + HX

The reaction of NH2OH with an aldehyde or ketone produces an oxime.

- R2C=O + NH2OH∙HCl , NaOH → R2C=NOH + NaCl + H2O

This reaction is useful in the purification of ketones and aldehydes: if hydroxylamine is added to an aldehyde or ketone in solution, an oxime forms, which generally precipitates from solution; heating the precipitate with an inorganic acid then restores the original aldehyde or ketone.[12]

Oximes, e.g., dimethylglyoxime, are also employed as ligands.

NH2OH reacts with chlorosulfonic acid to give hydroxylamine-O-sulfonic acid, a useful reagent for the synthesis of caprolactam.

- HOSO2Cl + NH2OH → NH2OSO2OH + HCl

The hydroxylamine-O-sulfonic acid, which should be stored at 0 °C to prevent decomposition, can be checked by iodometric titration.[clarification needed]

Hydroxylamine (NH2OH), or hydroxylamines (R-NHOH) can be reduced to amines.[13]

- NH2OH (Zn/HCl) → NH3

- R-NHOH (Zn/HCl) → R-NH2

Hydroxylamine explodes with heat:

- 4 NH2OH + O2 → 2 N2 + 6 H2O

The high reactivity comes in part from the partial isomerisation of the NH2OH structure to ammonia oxide (also known as azane oxide), with structure NH3+O−.[14]

Functional group

Substituted derivatives of hydroxylamine are known. If the hydroxyl hydrogen is substituted, this is called an O-hydroxylamine, if one of the amine hydrogens is substituted, this is called an N-hydroxylamine. In general N-hydroxylamines are the more common. Similarly to ordinary amines, one can distinguish primary, secondary and tertiary hydroxylamines, the latter two referring to compounds where two or three hydrogens are substituted, respectively. Examples of compounds containing a hydroxylamine functional group are N-tert-butyl-hydroxylamine or the glycosidic bond in calicheamicin. N,O-Dimethylhydroxylamine is a coupling agent, used to synthesize Weinreb amides.

- Synthesis

The most common method for the synthesis of substituted hydroxylamines is the oxidation of an amine with benzoyl peroxide. Some care must be taken to prevent over-oxidation to a nitrone. Other methods include:

- Hydrogenation of an oxime

- Alkylation of hydroxylamine

- The thermal degradation of amine oxides via the Cope reaction

Uses

Hydroxylamine and its salts are commonly used as reducing agents in myriad organic and inorganic reactions. They can also act as antioxidants for fatty acids.

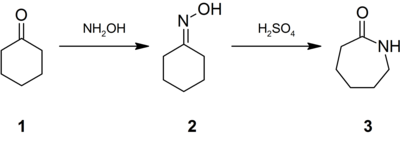

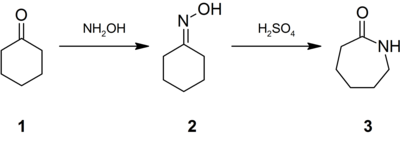

Conversion from cyclohexanone to caprolactam involving the Beckmann Rearrangement can be understood with this scheme.

In the synthesis of Nylon 6, cyclohexanone (1) is first converted to its oxime (2) by condensation with hydroxylamine. The treatment of this oxime with acid induces the Beckmann rearrangement to give caprolactam (3).[15] The latter can then undergo a ring-opening polymerization to yield Nylon 6.[16]

The nitrate salt, hydroxylammonium nitrate, is being researched as a rocket propellant, both in water solution as a monopropellant and in its solid form as a solid propellant.

This has also been used in the past by biologists to introduce random mutations by switching base pairs from G to A, or from C to T. This is to probe functional areas of genes to elucidate what happens if their functions are broken. Nowadays other mutagens are used.

Hydroxylamine can also be used to highly selectively cleave asparaginyl-glycine peptide bonds in peptides and proteins. It also bonds to and permanently disables (poisons) heme-containing enzymes. It is used as an irreversible inhibitor of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosynthesis on account of its similar structure to water.

This route also involves the Beckmann Rearrangement, like the conversion from cyclohexanone to caprolactam.

An alternative industrial synthesis of paracetamol developed by Hoechst–Celanese involves the conversion of ketone to a ketoxime with hydroxylamine.

Some non-chemical uses include removal of hair from animal hides and photographic developing solutions.[2] In the semiconductor industry, hydroxylamine is often a component in the "resist stripper", which removes photoresist after lithography.

Safety and environmental concerns

Hydroxylamine may explode on heating. The nature of the explosive hazard is not well understood. At least two factories dealing in hydroxylamine have been destroyed since 1999 with loss of life.[17] It is known, however, that ferrous and ferric iron salts accelerate the decomposition of 50% NH2OH solutions.[18] Hydroxylamine and its derivatives are more safely handled in the form of salts.

It is an irritant to the respiratory tract, skin, eyes, and other mucous membranes. It may be absorbed through the skin, is harmful if swallowed, and is a possible mutagen.[19]

Cytochrome P460, an enzyme found in the ammonia-oxidizing bacteria Nitrosomonas europea, can convert hydroxylamine to nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas.[20]

See also

References

- ^ "Front Matter". Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry : IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. p. 993. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-FP001. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- ^ a b Lide, David R., ed. (2006). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (87th ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0487-3.

- ^ Martel, B.; Cassidy, K. (2004). Chemical Risk Analysis: A Practical Handbook. Butterworth–Heinemann. p. 362. ISBN 978-1-903996-65-2.

- ^ a b c Greenwood and Earnshaw. Chemistry of the Elements. 2nd Edition. Reed Educational and Professional Publishing Ltd. pp. 431–432. 1997.

- ^ Lawton, Thomas J.; Ham, Jungwha; Sun, Tianlin; Rosenzweig, Amy C. (2014-09-01). "Structural conservation of the B subunit in the ammonia monooxygenase/particulate methane monooxygenase superfamily". Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics. 82 (9): 2263–2267. doi:10.1002/prot.24535. ISSN 1097-0134. PMC 4133332. PMID 24523098.

- ^ Arciero, David M.; Hooper, Alan B.; Cai, Mengli; Timkovich, Russell (1993-09-01). "Evidence for the structure of the active site heme P460 in hydroxylamine oxidoreductase of Nitrosomonas". Biochemistry. 32 (36): 9370–9378. doi:10.1021/bi00087a016. ISSN 0006-2960. PMID 8369308.

- ^ W. C. Lossen (1865) "Ueber das Hydroxylamine" (On hydroxylamine), Zeitschrift für Chemie, 8 : 551-553. From p. 551: "Ich schlage vor, dieselbe Hydroxylamin oder Oxyammoniak zu nennen." (I propose to call it hydroxylamine or oxyammonia.)

- ^ C. A. Lobry de Bruyn (1891) "Sur l'hydroxylamine libre" (On free hydroxylamine), Recueil des travaux chimiques des Pays-Bas, 10 : 100-112.

- ^ L. Crismer (1891) "Préparation de l'hydroxylamine cristallisée" (Preparation of crystalized hydroxylamine), Bulletin de la Société chimique de Paris, series 3, 6 : 793-795.

- ^ James Hale, Arthur (1919). The Manufacture of Chemicals by Electrolysis (1st ed.). New York: D. Van Nostrand Co. p. 32. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

manufacture of chemicals by electrolysis hydroxylamine 32.

- ^ Osswald, Philipp; Geisler, Walter (1941). Process of preparing hydroxylamine hydrochloride (US2242477) (PDF). U.S. Patent Office.

- ^ Ralph Lloyd Shriner, Reynold C. Fuson, and Daniel Y. Curtin, The Systematic Identification of Organic Compounds: A Laboratory Manual, 5th ed. (New York: Wiley, 1964), chapter 6.

- ^ Smith, Michael and Jerry March. March's advanced organic chemistry : reactions, mechanisms, and structure. New York. Wiley. p. 1554. 2001.

- ^ Kirby, AJ; Davies, JE; Fox, DJ; Hodgson, DR; Goeta, AE; Lima, MF; Priebe, JP; Santaballa, JA; Nome, F (28 February 2010). "Ammonia oxide makes up some 20% of an aqueous solution of hydroxylamine". Chemical Communications (Cambridge, England). 46 (8): 1302–4. doi:10.1039/b923742a. PMID 20449284.

- ^ Clayden, Jonathan; Greeves, Nick; Warren, Stuart (2012). Organic chemistry (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 958. ISBN 978-0-19-927029-3.

- ^ Nuyken, Oskar; Pask, Stephen (25 April 2013). "Ring-Opening Polymerization—An Introductory Review". Polymers. 5 (2): 361–403. doi:10.3390/polym5020361.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Japan Science and Technology Agency Failure Knowledge Database Archived 2007-12-20 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Cisneros, L. O.; Rogers, W. J.; Mannan, M. S.; Li, X.; Koseki, H. (2003). "Effect of Iron Ion in the Thermal Decomposition of 50 mass% Hydroxylamine/Water Solutions". J. Chem. Eng. Data. 48 (5): 1164–1169. doi:10.1021/je030121p.

- ^ MSDS Sigma-Aldrich

- ^ Caranto, Jonathan D.; Vilbert, Avery C.; Lancaster, Kyle M. (2016-12-20). "Nitrosomonas europaea cytochrome P460 is a direct link between nitrification and nitrous oxide emission". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (51): 14704–14709. doi:10.1073/pnas.1611051113. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5187719. PMID 27856762.

Further reading

- Hydroxylamine

- Walters, Michael A. and Andrew B. Hoem. "Hydroxylamine." e-Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. 2001.

- Schupf Computational Chemistry Lab

- M. W. Rathke A. A. Millard "Boranes in Functionalization of Olefins to Amines: 3-Pinanamine" Organic Syntheses, Coll. Vol. 6, p. 943; Vol. 58, p. 32. (preparation of hydroxylamine-O-sulfonic acid).