Little Boy

| Little Boy | |

|---|---|

A post-war Little Boy model | |

| Type | Nuclear weapon |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Los Alamos Laboratory |

| Produced | 1945 |

| No. built | 26 |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 9,700 pounds (4,400 kg) |

| Length | 10 feet (3.0 m) |

| Diameter | 28 inches (71 cm) |

| Filling | Uranium-235 |

| Filling weight | 64 kg |

| Blast yield | 15 kilotons of TNT (63 TJ) |

"Little Boy" was the codename for the type of atomic bomb dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 during World War II. It was the first nuclear weapon used in warfare. The bomb was dropped by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay piloted by Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, Jr., commander of the 509th Composite Group of the United States Army Air Forces and Captain Robert A. Lewis. It exploded with an energy of approximately 15 kilotons of TNT (63 TJ) and caused widespread death and destruction throughout the city. The Hiroshima bombing was the second man-made nuclear explosion in history, after the Trinity test.

Little Boy was developed by Lieutenant Commander Francis Birch's group at the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory during World War II, a reworking of their unsuccessful Thin Man nuclear bomb. Like Thin Man, it was a gun-type fission weapon, but it derived its explosive power from the nuclear fission of uranium-235, whereas Thin Man was based on fission of plutonium-239. Fission was accomplished by shooting a hollow cylinder of enriched uranium (the "bullet") onto a solid cylinder of the same material (the "target") by means of a charge of nitrocellulose propellant powder. It contained 64 kg (141 lb) of enriched uranium, although less than a kilogram underwent nuclear fission. Its components were fabricated at three different plants so that no one would have a copy of the complete design.

After the war ended, it was not expected that the inefficient Little Boy design would ever again be required, and many plans and diagrams were destroyed. However, by mid-1946, the Hanford Site reactors began suffering badly from the Wigner effect, the dislocation of atoms in a solid caused by neutron radiation, and plutonium became scarce, so six Little Boy assemblies were produced at Sandia Base. The Navy Bureau of Ordnance built another 25 Little Boy assemblies in 1947 for use by the Lockheed P2V Neptune nuclear strike aircraft which could be launched from the Midway-class aircraft carriers. All the Little Boy units were withdrawn from service by the end of January 1951.

Naming

Physicist Robert Serber named the first two atomic bomb designs during World War II based on their shapes: Thin Man and Fat Man. The "Thin Man" was a long, thin device and its name came from the Dashiell Hammett detective novel and series of movies about The Thin Man. The "Fat Man" was round and fat so it was named after Kasper Gutman, a rotund character in Hammett's 1930 novel The Maltese Falcon, played by Sydney Greenstreet in the 1941 film version. Little Boy was named by others as an allusion to Thin Man, since it was based on its design.[1]

Development

Because uranium-235 was known to be fissionable, it was the first material pursued in the approach to bomb development. As the first design developed (as well as the first deployed for combat), it is sometimes known as the Mark I.[2] The vast majority of the work came in the form of the isotope enrichment of the uranium necessary for the weapon, since uranium-235 makes up only 1 part in 140 of natural uranium.[3] Enrichment was performed at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where the electromagnetic separation plant, known as Y-12, became fully operational in March 1944.[4] The first shipments of highly enriched uranium were sent to the Los Alamos Laboratory in June 1944.[5]

Most of the uranium necessary for the production of the bomb came from the Shinkolobwe mine and was made available thanks to the foresight of the CEO of the High Katanga Mining Union, Edgar Sengier, who had 1,200 short tons (1,100 t) of uranium ore transported to a New York warehouse in 1940.[6] At least part of the 1,200 short tons (1,100 t) in addition to the uranium ore and uranium oxide captured by the Alsos Mission in 1944 and 1945 went to Oak Ridge for enrichment,[7] as did 1,232 pounds (559 kg) of uranium oxide captured on the Japan-bound German submarine U-234 after Germany's surrender in May 1945.[8]

Little Boy was a simplification of Thin Man, the previous gun-type fission weapon design. Thin Man, 17 feet (5.2 m) long, was designed to use plutonium, so it was also more than capable of using enriched uranium. The Thin Man design was abandoned after experiments by Emilio G. Segrè and his P-5 Group at Los Alamos on the newly reactor-produced plutonium from Oak Ridge and the Hanford site showed that it contained impurities in the form of the isotope plutonium-240. This has a far higher spontaneous fission rate and radioactivity than the cyclotron-produced plutonium on which the original measurements had been made, and its inclusion in reactor-bred plutonium (needed for bomb-making due to the quantities required) appeared unavoidable. This meant that the background fission rate of the plutonium was so high that it would be highly likely the plutonium would predetonate and blow itself apart in the initial forming of a critical mass.[9]

In July 1944, almost all research at Los Alamos was redirected to the implosion-type plutonium weapon. Overall responsibility for the uranium gun-type weapon was assigned to Captain William S. Parsons's Ordnance (O) Division. All the design, development, and technical work at Los Alamos was consolidated under Lieutenant Commander Francis Birch's group.[10] In contrast to the plutonium implosion-type nuclear weapon and the plutonium gun-type fission weapon, the uranium gun-type weapon was straightforward if not trivial to design. The concept was pursued so that in case of a failure to develop a plutonium bomb, it would still be possible to use the gun principle. The gun-type design henceforth had to work with enriched uranium only, and this allowed the Thin Man design to be greatly simplified. A high-velocity gun was no longer required, and a simpler weapon could be substituted. The simplified weapon was short enough to fit into a B-29 bomb bay.[11]

The design specifications were completed in February 1945, and contracts were let to build the components. Three different plants were used so that no one would have a copy of the complete design. The gun and breech were made by the Naval Gun Factory in Washington, D.C.; the target case and some other components by the Naval Ordnance Plant in Center Line, Michigan; and the tail fairing and mounting brackets by the Expert Tool and Die Company in Detroit, Michigan.[12] The bomb, except for the uranium payload, was ready at the beginning of May 1945.[13] Manhattan District Engineer Kenneth Nichols expected on 1 May 1945 to have uranium-235 "for one weapon before August 1 and a second one sometime in December", assuming the second weapon would be a gun type; designing an implosion bomb for uranium-235 was considered, and this would increase the production rate.[14] The uranium-235 projectile was completed on 15 June, and the target on 24 July.[15] The target and bomb pre-assemblies (partly assembled bombs without the fissile components) left Hunters Point Naval Shipyard, California, on 16 July aboard the heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis, arriving on 26 July.[16] The target inserts followed by air on 30 July.[15]

Although all of its components had been tested,[15] no full test of a gun-type nuclear weapon occurred before the Little Boy was dropped over Hiroshima. The only test explosion of a nuclear weapon concept had been of an implosion-type device employing plutonium as its fissile material, and took place on 16 July 1945 at the Trinity nuclear test. There were several reasons for not testing a Little Boy type of device. Primarily, there was little uranium-235 as compared with the relatively large amount of plutonium which, it was expected, could be produced by the Hanford Site reactors.[17] Additionally, the weapon design was simple enough that it was only deemed necessary to do laboratory tests with the gun-type assembly. Unlike the implosion design, which required sophisticated coordination of shaped explosive charges, the gun-type design was considered almost certain to work.[18]

Though Little Boy incorporated various safety mechanisms, an accidental detonation was nonetheless possible. For example, should the bomber carrying the device crash then the hollow "bullet" could be driven into the "target" cylinder, detonating the bomb or at least releasing massive amounts of radiation; tests showed that this would require a highly unlikely impact of 500 times the force of gravity.[19] Another concern was that a crash and fire could trigger the explosives.[20] If immersed in water, the uranium components were subject to a neutron moderator effect, which would not cause an explosion but would release radioactive contamination. For this reason, pilots were advised to crash on land rather than at sea.[19]

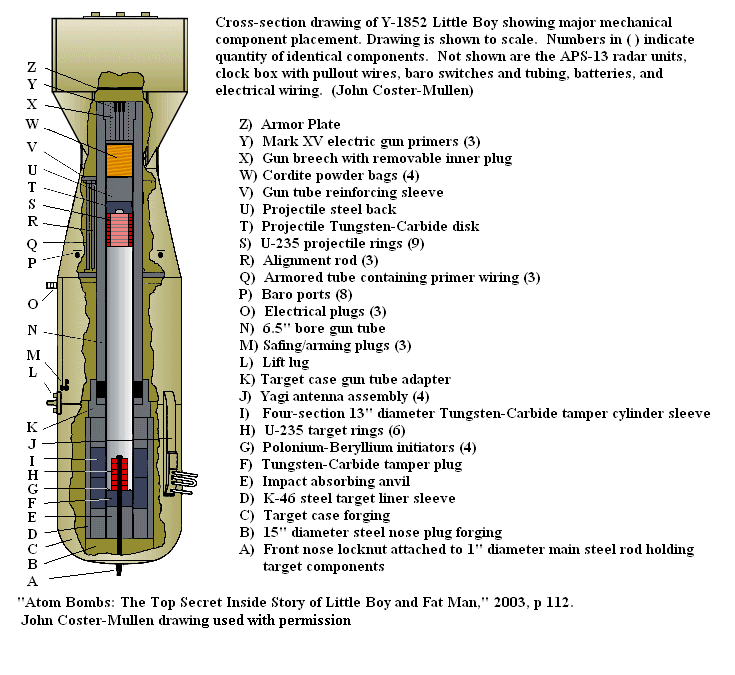

Design

The Little Boy was 120 inches (300 cm) in length, 28 inches (71 cm) in diameter and weighed approximately 9,700 pounds (4,400 kg).[21] The design used the gun method to explosively force a hollow sub-critical mass of enriched uranium and a solid target cylinder together into a super-critical mass, initiating a nuclear chain reaction.[22] This was accomplished by shooting one piece of the uranium onto the other by means of four cylindrical silk bags of cordite powder. This was a widely used smokeless propellant consisting of a mixture of 65 percent nitrocellulose, 30 percent nitroglycerine, 3 percent petroleum jelly, and 3 percent carbamite that was extruded into tubular granules. This gave it a high surface area and a rapid burning area, and could attain pressures of up to 40,000 pounds per square inch (280,000 kPa). Cordite for the wartime Little Boy was sourced from Canada; propellant for post-war Little Boys was obtained from the Picatinny Arsenal.[23] The bomb contained 64 kg (141 lb) of enriched uranium. Most was enriched to 89% but some was only 50% uranium-235, for an average enrichment of 80%.[22] Less than a kilogram of uranium underwent nuclear fission, and of this mass only 0.6 g (0.021 oz) was transformed into several forms of energy, mostly kinetic energy, but also heat and radiation.[24]

Assembly details

Inside the weapon, the uranium-235 material was divided into two parts, following the gun principle: the "projectile" and the "target". The projectile was a hollow cylinder with 60% of the total mass (38.5 kg (85 lb)). It consisted of a stack of nine uranium rings, each 6.25-inch (159 mm) in diameter with a 4-inch (100 mm) bore in the center, and a total length of 7 inches (180 mm), pressed together into the front end of a thin-walled projectile 16.25 inches (413 mm) long. Filling in the remainder of the space behind these rings in the projectile was a tungsten carbide disc with a steel back. At ignition, the projectile slug was pushed 42 inches (1,100 mm) along the 72-inch (1,800 mm) long, 6.5-inch (170 mm) smooth-bore gun barrel. The slug "insert" was a 4 inches (100 mm) cylinder, 7 inches (180 mm) in length with a 1 inch (25 mm) axial hole. The slug comprised 40% of the total fissile mass (25.6 kg or 56 lb). The insert was a stack of six washer-like uranium discs somewhat thicker than the projectile rings that were slid over a 1 inch (25 mm) rod. This rod then extended forward through the tungsten carbide tamper plug, impact-absorbing anvil, and nose plug backstop, eventually protruding out of the front of the bomb casing. This entire target assembly was secured at both ends with locknuts.[25][26]

When the hollow-front projectile reached the target and slid over the target insert, the assembled super-critical mass of uranium would be completely surrounded by a tamper and neutron reflector of tungsten carbide and steel, both materials having a combined mass of 2,300 kg (5,100 lb).[27] Neutron initiators at the base of the projectile were activated by the impact.[28]

Counter-intuitive design

For the first fifty years after 1945, every published description and drawing of the Little Boy mechanism assumed that a small, solid projectile was fired into the center of a larger, stationary target.[29] However, critical mass considerations dictated that in Little Boy the larger, hollow piece would be the projectile. The assembled fissile core had more than two critical masses of uranium-235. This required one of the two pieces to have more than one critical mass, with the larger piece avoiding criticality prior to assembly by means of shape and minimal contact with the neutron-reflecting tungsten carbide tamper.

A hole in the center of the larger piece dispersed the mass and increased the surface area, allowing more fission neutrons to escape, thus preventing a premature chain reaction.[30] But, for this larger, hollow piece to have minimal contact with the tamper, it must be the projectile, since only the projectile's back end was in contact with the tamper prior to detonation. The rest of the tungsten carbide surrounded the sub-critical mass target cylinder (called the "insert" by the designers) with air space between it and the insert. This arrangement packs the maximum amount of fissile material into a gun-assembly design.[30]

Fuze system

The fuzing system was designed to trigger at the most destructive altitude, which calculations suggested was 580 metres (1,900 ft). It employed a three-stage interlock system:[31]

- A timer ensured that the bomb would not explode until at least fifteen seconds after release, one-quarter of the predicted fall time, to ensure safety of the aircraft. The timer was activated when the electrical pull-out plugs connecting it to the airplane pulled loose as the bomb fell, switching it to its internal 24–volt battery and starting the timer. At the end of the 15 seconds, the bomb would be 3,600 feet (1,100 m) from the aircraft, and the radar altimeters were powered up and responsibility was passed to the barometric stage.[31]

- The purpose of the barometric stage was to delay activating the radar altimeter firing command circuit until near detonation altitude. A thin metallic membrane enclosing a vacuum chamber (a similar design is still used today in old-fashioned wall barometers) gradually deformed as ambient air pressure increased during descent. The barometric fuze was not considered accurate enough to detonate the bomb at the precise ignition height, because air pressure varies with local conditions. When the bomb reached the design height for this stage (reportedly 2,000 metres, 6,600 ft), the membrane closed a circuit, activating the radar altimeters. The barometric stage was added because of a worry that external radar signals might detonate the bomb too early.[31]

- Two or more redundant radar altimeters were used to reliably detect final altitude. When the altimeters sensed the correct height, the firing switch closed, igniting the three BuOrd Mk15, Mod 1 Navy gun primers in the breech plug, which set off the charge consisting of four silk powder bags each containing 2 pounds (0.9 kg) of WM slotted-tube cordite. This launched the uranium projectile towards the opposite end of the gun barrel at an eventual muzzle velocity of 300 metres per second (980 ft/s). Approximately 10 milliseconds later the chain reaction occurred, lasting less than 1 microsecond. The radar altimeters used were modified U.S. Army Air Corps APS-13 tail warning radars, nicknamed "Archie", normally used to warn a fighter pilot of another plane approaching from behind.[31]

Rehearsals

The Little Boy pre-assemblies were designated L-1, L-2, L-3, L-4, L-5, L-6, L-7, and L-11. L-1, L-2, L-5, and L-6 were expended in test drops. The first drop test was conducted with L-1 on 23 July 1945. It was dropped over the sea near Tinian in order to test the radar altimeter by the B-29 later known as Big Stink, piloted by Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, the commander of the 509th Composite Group. Two more drop tests over the sea were made on 24 and 25 July, using the L-2 and L-5 units in order to test all components. Tibbets was the pilot for both missions, but this time the bomber used was the one subsequently known as Jabit. L-6 was used as a dress rehearsal on 29 July. The B-29 Next Objective, piloted by Major Charles W. Sweeney, flew to Iwo Jima, where emergency procedures for loading the bomb onto a standby aircraft were practiced. This rehearsal was repeated on 31 July, but this time L-6 was reloaded onto a different B-29, Enola Gay, piloted by Tibbets, and the bomb was test dropped near Tinian. L-11 was the assembly used for the Hiroshima bomb.[32][33]

Bombing of Hiroshima

Parsons, the Enola Gay's weaponeer, was concerned about the possibility of an accidental detonation if the plane crashed on takeoff, so he decided not to load the four cordite powder bags into the gun breech until the aircraft was in flight. After takeoff, Parsons and his assistant, Second Lieutenant Morris R. Jeppson, made their way into the bomb bay along the narrow catwalk on the port side. Jeppson held a flashlight while Parsons disconnected the primer wires, removed the breech plug, inserted the powder bags, replaced the breech plug, and reconnected the wires. Before climbing to altitude on approach to the target, Jeppson switched the three safety plugs between the electrical connectors of the internal battery and the firing mechanism from green to red. The bomb was then fully armed. Jeppson monitored the bomb's circuits.[34]

The bomb was dropped at approximately 08:15 (JST) 6 August 1945. After falling for 44.4 seconds, the time and barometric triggers started the firing mechanism. The detonation happened at an altitude of 1,968 ± 50 feet (600 ± 15 m). It was less powerful than the Fat Man, which was dropped on Nagasaki, but the damage and the number of victims at Hiroshima were much higher, as Hiroshima was on flat terrain, while the hypocenter of Nagasaki lay in a small valley. According to figures published in 1945, 66,000 people were killed as a direct result of the Hiroshima blast, and 69,000 were injured to varying degrees.[35] Of those deaths, 20,000 were members of the Imperial Japanese Army.[36]

The exact measurement of the yield was problematic since the weapon had never been tested. President Harry S. Truman officially announced that the yield was 20 kilotons of TNT (84 TJ). This was based on Parsons's visual assessment that the blast was greater than what he had seen at the Trinity nuclear test. Since that had been estimated at 18 kilotons of TNT (75 TJ), speech writers rounded up to 20 kilotons. Further discussion was then suppressed, for fear of lessening the impact of the bomb on the Japanese. Data had been collected by Luis Alvarez, Harold Agnew, and Lawrence H. Johnston on the instrument plane, The Great Artiste, but this was not used to calculate the yield at the time.[37]

After hostilities ended, a survey team from the Manhattan Project that included William Penney, Robert Serber, and George T. Reynolds was sent to Hiroshima to evaluate the effects of the blast. From evaluating the effects on objects and structures, Penney concluded that the yield was 12 ± 1 kilotons.[38] Later calculations based on charring pointed to a yield of 13 to 14 kilotons.[39] In 1953, Frederick Reines calculated the yield as 15 kilotons of TNT (63 TJ).[37] This figure became the official yield.[40]

Project Ichiban

In 1962, scientists at Los Alamos created a mockup of Little Boy known as "Project Ichiban" in order to answer some of the unanswered questions, but it failed to clear up all the issues. In 1982, Los Alamos created a replica Little Boy from the original drawings and specifications. This was then tested with enriched uranium but in a safe configuration that would not cause a nuclear explosion. A hydraulic lift was used to move the projectile, and experiments were run to assess neutron emission.[41] Based on this and the data from The Great Artiste, the yield was estimated at 16.6 ± 0.3 kilotons.[42] After considering many estimation methods, a 1985 report concluded that the yield was 15 kilotons of TNT (63 TJ) ± 20%.[40]

Physical effects

After being selected in April 1945, Hiroshima was spared conventional bombing to serve as a pristine target, where the effects of a nuclear bomb on an undamaged city could be observed.[43] While damage could be studied later, the energy yield of the untested Little Boy design could be determined only at the moment of detonation, using instruments dropped by parachute from a plane flying in formation with the one that dropped the bomb. Radio-transmitted data from these instruments indicated a yield of about 15 kilotons.[40]

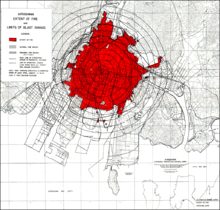

Comparing this yield to the observed damage produced a rule of thumb called the 5 pounds per square inch (34 kPa) lethal area rule. Approximately 100% of people inside the area where the shock wave carries such an overpressure or greater would be killed.[44] At Hiroshima, that area was 3.5 kilometres (2.2 mi) in diameter.[45]

The damage came from three main effects: blast, fire, and radiation.[46]

Blast

The blast from a nuclear bomb is the result of X-ray-heated air (the fireball) sending a shock wave or pressure wave in all directions, initially at a velocity greater than the speed of sound,[47] analogous to thunder generated by lightning. Knowledge about urban blast destruction is based largely on studies of Little Boy at Hiroshima. Nagasaki buildings suffered similar damage at similar distances, but the Nagasaki bomb detonated 3.2 kilometres (2.0 mi) from the city center over hilly terrain that was partially bare of buildings.[48]

In Hiroshima almost everything within 1.6 kilometres (1.0 mi) of the point directly under the explosion was completely destroyed, except for about 50 heavily reinforced, earthquake-resistant concrete buildings, only the shells of which remained standing. Most were completely gutted, with their windows, doors, sashes, and frames ripped out.[49] The perimeter of severe blast damage approximately followed the 5 psi (34 kPa) contour at 1.8 kilometres (1.1 mi).

Later test explosions of nuclear weapons with houses and other test structures nearby confirmed the 5 psi overpressure threshold. Ordinary urban buildings experiencing it will be crushed, toppled, or gutted by the force of air pressure. The picture at right shows the effects of a nuclear-bomb-generated 5 psi pressure wave on a test structure in Nevada in 1953.[50]

A major effect of this kind of structural damage was that it created fuel for fires that were started simultaneously throughout the severe destruction region.

Fire

The first effect of the explosion was blinding light, accompanied by radiant heat from the fireball. The Hiroshima fireball was 370 metres (1,200 ft) in diameter, with a surface temperature of 6,000 °C (10,830 °F).[51] Near ground zero, everything flammable burst into flame. One famous, anonymous Hiroshima victim, sitting on stone steps 260 metres (850 ft) from the hypocenter, left only a shadow, having absorbed the fireball heat that permanently bleached the surrounding stone.[52] Simultaneous fires were started throughout the blast-damaged area by fireball heat and by overturned stoves and furnaces, electrical shorts, etc. Twenty minutes after the detonation, these fires had merged into a firestorm, pulling in surface air from all directions to feed an inferno which consumed everything flammable.[53]

The Hiroshima firestorm was roughly 3.2 kilometres (2.0 mi) in diameter, corresponding closely to the severe blast damage zone. (See the USSBS[54] map, right.) Blast-damaged buildings provided fuel for the fire. Structural lumber and furniture were splintered and scattered about. Debris-choked roads obstructed fire fighters. Broken gas pipes fueled the fire, and broken water pipes rendered hydrants useless.[53] At Nagasaki, the fires failed to merge into a single firestorm, and the fire-damaged area was only one fourth as great as at Hiroshima, due in part to a southwest wind that pushed the fires away from the city.[55]

As the map shows, the Hiroshima firestorm jumped natural firebreaks (river channels), as well as prepared firebreaks. The spread of fire stopped only when it reached the edge of the blast-damaged area, encountering less available fuel.[56]

Accurate casualty figures are impossible to determine, because many victims were cremated by the firestorm, along with all record of their existence. The Manhattan Project report on Hiroshima estimated that 60% of immediate deaths were caused by fire, but with the caveat that "many persons near the center of explosion suffered fatal injuries from more than one of the bomb effects."[57] In particular, many fire victims also received lethal doses of nuclear radiation.

Radiation

Local fallout is dust and ash from a bomb crater, contaminated with radioactive fission products. It falls to earth downwind of the crater and can produce, with radiation alone, a lethal area much larger than that from blast and fire. With an air burst, the fission products rise into the stratosphere, where they dissipate and become part of the global environment. Because Little Boy was an air burst 580 metres (1,900 ft) above the ground, there was no bomb crater and no local radioactive fallout.[58]

However, a burst of intense neutron and gamma radiation came directly from the fireball. Its lethal radius was 1.3 kilometres (0.8 mi),[45] covering about half of the firestorm area. An estimated 30% of immediate fatalities were people who received lethal doses of this direct radiation, but died in the firestorm before their radiation injuries would have become apparent. Over 6,000 people survived the blast and fire, but died of radiation injuries.[57] Among injured survivors, 30% had radiation injuries[59] from which they recovered, but with a lifelong increase in cancer risk.[60][61] To date, no radiation-related evidence of heritable diseases has been observed among the survivors' children.[62][63][64]

Conventional weapon equivalent

Although Little Boy exploded with the energy equivalent of 16,000 tons of TNT, the Strategic Bombing Survey estimated that the same blast and fire effect could have been caused by 2,100 tons of conventional bombs: "220 B-29s carrying 1,200 tons of incendiary bombs, 400 tons of high-explosive bombs, and 500 tons of anti-personnel fragmentation bombs."[65] Since the target was spread across a two-dimensional plane, the vertical component of a single spherical nuclear explosion was largely wasted. A cluster bomb pattern of smaller explosions would have been a more energy-efficient match to the target.[65]

Post-war

When the war ended, it was not expected that the inefficient Little Boy design would ever again be required, and many plans and diagrams were destroyed. However, by mid-1946 the Hanford Site reactors were suffering badly from the Wigner effect. Faced with the prospect of no more plutonium for new cores and no more polonium for the initiators for the cores that had already been produced, the Director of the Manhattan Project, Major General Leslie R. Groves, ordered that some Little Boys be prepared as an interim measure until a cure could be found. No Little Boy assemblies were available, and no comprehensive set of diagrams of the Little Boy could be found, although there were drawings of the various components, and stocks of spare parts.[66][67]

At Sandia Base, three Army officers, Captains Albert Bethel, Richard Meyer, and Bobbie Griffin attempted to re-create the Little Boy. They were supervised by Harlow W. Russ, an expert on Little Boy who served with Project Alberta on Tinian, and was now leader of the Z-11 Group of the Los Alamos Laboratory's Z Division at Sandia. Gradually, they managed to locate the correct drawings and parts, and figured out how they went together. Eventually, they built six Little Boy assemblies. Although the casings, barrels, and components were tested, no enriched uranium was supplied for the bombs. By early 1947, the problem caused by the Wigner effect was on its way to solution, and the three officers were reassigned.[66][67]

The Navy Bureau of Ordnance built 25 Little Boy assemblies in 1947 for use by the nuclear-capable Lockheed P2V Neptune aircraft carrier aircraft (which could be launched from but not land on the Midway-class aircraft carriers). Components were produced by the Naval Ordnance Plants in Pocatello, Idaho, and Louisville, Kentucky. Enough fissionable material was available by 1948 to build ten projectiles and targets, although there were only enough initiators for six.[68] All the Little Boy units were withdrawn from service by the end of January 1951.[69][70]

The Smithsonian Institution displayed a Little Boy (complete, except for enriched uranium), until 1986. The Department of Energy took the weapon from the museum to remove its inner components, so the bombs could not be stolen and detonated with fissile material. The government returned the emptied casing to the Smithsonian in 1993. Three other disarmed bombs are on display in the United States; another is at the Imperial War Museum in London.[29]

Notes

- ^ Serber & Crease 1998, p. 104.

- ^ Hansen 1995, p. V-105.

- ^ Jones 1985, p. 9.

- ^ Jones 1985, p. 138.

- ^ Jones 1985, p. 143.

- ^ Jones 1985, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Rhodes 1995, pp. 160–161.

- ^ "The Sensational Surrender of Four Nazi U-boats at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard". New England Historical Society. 15 May 2015. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 228.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 245–249.

- ^ Rhodes 1986, p. 541.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 257.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 262.

- ^ Nichols 1987, pp. 175–176.

- ^ a b c Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 265.

- ^ Coster-Mullen 2012, p. 30.

- ^ Hansen 1995, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 293.

- ^ a b Hansen 1995, p. 113.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 333.

- ^ Gosling 1999, p. 51.

- ^ a b Coster-Mullen 2012, p. 18.

- ^ Coster-Mullen 2012, p. 27.

- ^ Glasstone & Dolan 1977, p. 12.

- ^ Sublette, Carey. "Nuclear Weapons Frequently Asked Questions, Section 8.0: The First Nuclear Weapons". Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ^ Coster-Mullen 2012, pp. 18–19, 27.

- ^ Bernstein 2007, p. 133.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 263–265.

- ^ a b Samuels 2008.

- ^ a b Coster-Mullen 2012, pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b c d Hansen 1995a, pp. 2–5.

- ^ Campbell 2005, pp. 46, 80.

- ^ Coster-Mullen 2012, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Coster-Mullen 2012, pp. 34–35.

- ^ The Manhattan Engineer District (29 June 1945). "The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki". Project Gutenberg Ebook. docstoc.com. p. 3.

- ^ Alan Axelrod (6 May 2008). The Real History of World War II: A New Look at the Past. Sterling. p. 350.

- ^ a b Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 393.

- ^ Malik 1985, pp. 18–20.

- ^ Malik 1985, p. 21.

- ^ a b c Malik 1985, p. 1.

- ^ Coster-Mullen 2012, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Malik 1985, p. 16.

- ^ Glasstone 1962, p. 629.

- ^ a b Glasstone & Dolan 1977, p. Nuclear Bomb Effects Computer.

- ^ Glasstone & Dolan 1977, p. 1.

- ^ Diacon 1984, p. 18.

- ^ Glasstone & Dolan 1977, pp. 300, 301.

- ^ The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, 1946, p. 14.

- ^ Glasstone & Dolan 1977, p. 179.

- ^ Nuclear Weapon Thermal Effects 1998.

- ^ Human Shadow Etched in Stone.

- ^ a b Glasstone & Dolan 1977, pp. 300–304.

- ^ D'Olier 1946, pp. 22–25.

- ^ Glasstone & Dolan 1977, p. 304.

- ^ The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, 1946, pp. 21–23.

- ^ a b The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, 1946, p. 21.

- ^ Glasstone & Dolan 1977, p. 409 "An air burst, by definition, is one taking place at such a height above the earth that no appreciable quantities of surface material are taken up into the fireball. ... the deposition of early fallout from an air burst will generally not be significant. An air burst, however, may produce some induced radioactive contamination in the general vicinity of ground zero as a result of neutron capture by elements in the soil." p. 36, "at Hiroshima ... injuries due to fallout were completely absent.".

- ^ Glasstone & Dolan 1977, pp. 545, 546.

- ^ Richardson RR 2009.

- ^ "The ongoing research into the effects of radiation". Radio Netherlands Archives. 31 July 2005. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- ^ Genetic Effects.

- ^ Izumi BJC 2003.

- ^ Izumi IJC 2003.

- ^ a b D'Olier 1946, p. 24.

- ^ a b Coster-Mullen 2012, p. 85.

- ^ a b Abrahamson & Carew 2002, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Hansen 1995, pp. 116–118.

- ^ Hansen 1995, p. 3.

- ^ "Chart of Strategic Nuclear Bombs". strategic-air-command.com.

References

- Abrahamson, James L.; Carew, Paul H. (2002). Vanguard of American Atomic Deterrence. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-97819-2. OCLC 49859889.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki" (PDF). The Manhattan Engineer District. 29 June 1946. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 6 November 2013. This report can also be found here and here.

- Bernstein, Jeremy (2007). Nuclear Weapons: What You Need to Know. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88408-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Campbell, Richard H. (2005). The Silverplate Bombers: A History and Registry of the Enola Gay and Other B-29s Configured to Carry Atomic Bombs. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-2139-8. OCLC 58554961.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Coster-Mullen, John (2012). Atom Bombs: The Top Secret Inside Story of Little Boy and Fat Man. Waukesha, Wisconsin: J. Coster-Mullen. OCLC 298514167.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Diacon, Diane (1984). Residential Housing and Nuclear Attack. London: Croom Helm. ISBN 978-0-7099-0868-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - D'Olier, Franklin, ed. (1946). United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Summary Report (Pacific War). Washington: United States Government Printing Office. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) This report can also be found here. - "Genetic Effects: Question #7". Radiation Effects Research Foundation. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- Glasstone, Samuel (1962). The Effects of Nuclear Weapons, Revised Edition. United States: United States Department of Defense and United States Atomic Energy Commission. ISBN 978-1258793555.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Glasstone, Samuel; Dolan, Philip J. (1977). The Effects of Nuclear Weapons, Third Edition. United States: United States Department of Defense and United States Department of Energy. ISBN 978-1603220163.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gosling, F. G. (1999). The Manhattan Project: Making the Atomic Bomb. Diane Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7881-7880-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Groves, Leslie R. (1962). Now it Can Be Told: the Story of the Manhattan Project. New York: Da Capo Press (1975 reprint). ISBN 0-306-70738-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hansen, Chuck (1995). Volume V: US Nuclear Weapons Histories. Swords of Armageddon: US Nuclear Weapons Development since 1945. Sunnyvale, California: Chuckelea Publications. ISBN 978-0-9791915-0-3. OCLC 231585284.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hansen, Chuck (1995a). Volume VII: The Development of US Nuclear Weapons. Swords of Armageddon: US Nuclear Weapons Development since 1945. Sunnyvale, California: Chuckelea Publications. ISBN 978-0-9791915-7-2. OCLC 231585284.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hoddeson, Lillian; Henriksen, Paul W.; Meade, Roger A.; Westfall, Catherine L. (1993). Critical Assembly: A Technical History of Los Alamos During the Oppenheimer Years, 1943–1945. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44132-3. OCLC 26764320.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Human Shadow Etched in Stone". Photographic Display. Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- Izumi S, Koyama K, Soda M, Suyama A (November 2003). "Cancer incidence in children and young adults did not increase relative to parental exposure to atomic bombs". British Journal of Cancer. 89 (9): 1709–1713. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6601322. PMC 2394417. PMID 14583774.

- Izumi S, Suyama A, Koyama K (November 2003). "Radiation-related mortality among offspring of atomic bomb survivors: a half-century of follow-up". International Journal of Cancer. 107 (2): 292–297. doi:10.1002/ijc.11400. PMID 12949810.

- Jones, Vincent (1985). Manhattan: The Army and the Atomic Bomb (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 10913875. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Malik, John S. (1985). "The yields of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki nuclear explosions" (PDF). Los Alamos National Laboratory report number LA-8819. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nichols, Kenneth (1987). The Road to Trinity: A Personal Account of How America's Nuclear Policies Were Made. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 068806910X. OCLC 15223648.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Nuclear Weapon Thermal Effects". Special Weapons Primer, Weapons of Mass Destruction. Federation of American Scientists. 1998. Archived from the original on 22 April 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- Rhodes, Richard (1986). The Making of the Atomic Bomb. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-81378-5. OCLC 13793436.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rhodes, Richard (1995). Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb. New York: Touchstone. ISBN 0-684-82414-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Richardson, David; et al. (September 2009). "Ionizing Radiation and Leukemia Mortality among Japanese Atomic Bomb Survivors, 1950–2000". Radiation Research. 172 (3): 368–382. Bibcode:2009RadR..172..368R. doi:10.1667/RR1801.1. PMID 19708786. S2CID 12463437.

- Samuels, David (15 December 2008). "Atomic John: A truck driver uncovers secrets about the first nuclear bombs". The New Yorker. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Serber, Robert; Crease, Robert P. (1998). Peace & War: Reminiscences of a Life on the Frontiers of Science. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231105460. OCLC 37631186.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Little Boy description at Carey Sublette's NuclearWeaponArchive.org

- Nuclear Files.org Definition and explanation of 'Little Boy'

- The Nuclear Weapon Archive

- Simulation of "Little Boy" an interactive simulation of "Little Boy"

- Little Boy 3D Model

- Hiroshima & Nagasaki Remembered information about preparation and dropping the Little Boy bomb

- Little boy Nuclear Bomb at Imperial War museum London UK (jpg)