Joris-Karl Huysmans

Joris–Karl Huysmans | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Charles-Marie-Georges Huysmans 5 February 1848 Paris, French Second Republic |

| Died | 12 May 1907 (aged 59) Paris, Third French Republic |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Nationality | French |

| Genre | Fictional prose |

| Literary movement | Decadent |

| Notable works | À rebours (1884), Là-bas (1891), En route (1895), La cathédrale (1898) |

Charles-Marie-Georges Huysmans (US: /wiːsˈmɒ̃s/,[1] French: [ʃaʁl maʁi ʒɔʁʒ ɥismɑ̃s]; 5 February 1848 – 12 May 1907) was a French novelist and art critic who published his works as Joris-Karl Huysmans (pronounced [ʒoʁis kaʁl -], variably abbreviated as J. K. or J.-K.). He is most famous for the novel À rebours (1884, published in English as Against the Grain or Against Nature). He supported himself by a 30-year career in the French civil service.

Huysmans' work is considered remarkable for its idiosyncratic use of the French language, large vocabulary, descriptions, satirical wit and far-ranging erudition. First considered part of Naturalism, he became associated with the decadent movement with his publication of À rebours. His work expressed his deep pessimism, which had led him to the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer.[2] In later years, his novels reflected his study of Catholicism, religious conversion, and becoming an oblate. He discussed the iconography of Christian architecture at length in La cathédrale (1898), set at Chartres and with its cathedral as the focus of the book.

Là-bas (1891), En route (1895) and La cathédrale (1898) are a trilogy that feature Durtal, an autobiographical character whose spiritual progress is tracked and who converts to Catholicism. In the novel that follows, L'Oblat (1903), Durtal becomes an oblate in a monastery, as Huysmans himself was in the Benedictine Abbey at Ligugé, near Poitiers, in 1901.[3][4] La cathédrale was his most commercially successful work. Its profits enabled Huysmans to retire from his civil service job and live on his royalties.

| French and Francophone literature |

|---|

| by category |

| History |

| Movements |

| Writers |

| Countries and regions |

| Portals |

Parents and early life

Huysmans was born in Paris in 1848. His father Godfried Huysmans was Dutch, and a lithographer by trade. His mother Malvina Badin Huysmans had been a schoolmistress. Huysmans' father died when he was eight years old. After his mother quickly remarried, Huysmans resented his stepfather, Jules Og, a Protestant who was part-owner of a Parisian book-bindery.

During childhood, Huysmans turned away from the Roman Catholic Church. He was unhappy at school but completed his coursework and earned a baccalauréat.

Civil service career

For 32 years, Huysmans worked as a civil servant for the French Ministry of the Interior, a job he found tedious. The young Huysmans was called up to fight in the Franco-Prussian War, but was invalided out with dysentery. He used this experience in an early story, "Sac au dos" (Backpack) (later included in his collection, Les Soirées de Médan).

After his retirement from the Ministry in 1898, made possible by the commercial success of his novel, La cathédrale, Huysmans planned to leave Paris and move to Ligugé. He intended to set up a community of Catholic artists, including Charles-Marie Dulac (1862-1898). He had praised the young painter in La cathédrale. Dulac died a few months before Huysmans completed his arrangements for the move to Ligugé, and he decided to stay in Paris.

In addition to his novels, Huysmans was known for his art criticism in L'Art moderne (1883) and Certains (1889). He was a founding member of the Académie Goncourt. An early advocate of Impressionism, he admired such artists as Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon.

In 1905 Huysmans was diagnosed with cancer of the mouth. He died in 1907 and was interred in the cimetière du Montparnasse, Paris.

Personal life

Huysmans never married or had children. He had a long-term, on-and-off relationship with Anna Meunier, a seamstress.[5][6][7]

Writing career

He used the name Joris-Karl Huysmans when he published his writing, as a way of honoring his father's ancestry. His first major publication was a collection of prose poems, Le drageoir aux épices (1874), which were strongly influenced by Baudelaire. They attracted little attention but revealed flashes of the author's distinctive style.

Huysmans followed it with the novel, Marthe, Histoire d'une fille (1876). The story of a young prostitute, it was closer to Naturalism and brought him to the attention of Émile Zola. His next works were similar: sombre, realistic and filled with detailed evocations of Paris, a city Huysmans knew intimately. Les Soeurs Vatard (1879), dedicated to Zola, deals with the lives of women in a bookbindery. En ménage (1881) is an account of a writer's failed marriage. The climax of his early work is the novella À vau-l'eau (1882) (Downstream or With the Flow), the story of a downtrodden clerk, Monsieur Folantin, and his quest for a decent meal.

Huysmans' novel À rebours (Against the Grain or Against Nature or Wrong Way; 1884) became his most famous, or notorious. It featured the character of an aesthete, des Esseintes, and decisively broke from Naturalism. It was seen as an example of "decadent" literature. The description of des Esseintes' "alluring liaison" with a "cherry-lipped youth" was believed to have influenced other writers of the decadent movement, including Oscar Wilde.[8]

It is now considered an important step in the formation of "gay literature".[8] À rebours gained notoriety as an exhibit in the trials of Oscar Wilde in 1895. The prosecutor referred to it as a "sodomitical" book. The book appalled Zola, who felt it had dealt a "terrible blow" to Naturalism.[9]

Huysmans began to drift away from the Naturalists and found new friends among the Symbolist and Catholic writers whose work he had praised in À rebours. They included Jules Barbey d'Aurevilly, Villiers de L'Isle Adam and Léon Bloy. Stéphane Mallarmé was so pleased with the publicity his verse had received from the novel that he dedicated one of his most famous poems, "Prose pour des Esseintes", to its hero. Barbey d'Aurevilly told Huysmans that after writing À rebours, he would have to choose between "the muzzle of a pistol and the foot of the Cross." Huysmans, who had received a secular education and abandoned his Catholic religion in childhood, returned to the Catholic Church eight years later.[9]

Huysmans' next novel, En rade, an unromantic account of a summer spent in the country, did not sell as well as its predecessor.

His Là-bas (1891) attracted considerable attention for its portrayal of Satanism in France in the late 1880s.[10][11] He introduced the character Durtal, a thinly disguised self-portrait. The later Durtal novels, En route (1895), La cathédrale (1898) and L'oblat (1903), explore Durtal/Huysmans' conversion to Roman Catholicism.[12] En route depicts Durtal's spiritual struggle during his stay at a Trappist monastery. In La cathédrale (1898), the protagonist is at Chartres, intensely studying the cathedral and its symbolism. The commercial success of this book enabled Huysmans to retire from the civil service and live on his royalties. In L'Oblat, Durtal becomes a Benedictine oblate. He finally learns to accept the world's suffering.

Huysmans' work was known for his idiosyncratic use of the French language, extensive vocabulary, detailed and sensuous descriptions, and biting, satirical wit. It also displays an encyclopaedic erudition, ranging from the catalogue of decadent Latin authors in À rebours to the discussion of the iconography of Christian architecture in La cathédrale. Huysmans expresses a disgust with modern life and a deep pessimism. This had led him first to the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer. Later he returned to the Catholic Church, as noted in his Durtal novels.

Honors

Huysmans was made a Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur in 1892, for his work with the civil service. In 1905, his admirers persuaded the French government to promote him to Officier de la Légion d'honneur for his literary achievements.

Style and Influence

This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: "Section is mainly a list of quotations with no unifying formatting, making the sources unclear for some of the material. (December 2018) |

"It takes me two years to 'document' myself for a novel – two years of hard work. That is the trouble with the naturalistic novel – it requires so much documentary care. I never make, like Zola, a plan for a book. I know how it will begin and how it will end – that's all. When I finally get to writing it, it goes along rather fast – assez vite."[13]

"Barbaric in its profusion, violent in its emphasis, wearying in its splendor, it is – especially in regard to things seen – extraordinarily expressive, with all the shades of a painter's palette. Elaborately and deliberately perverse, it is in its very perversity that Huysmans' work - so fascinating, so repellent, so instinctively artificial - comes to represent, as the work of no other writer can be said to do, the main tendencies, the chief results, of the Decadent movement in literature." (Arthur Symons, The Decadent Movement in Literature)

"...Continually dragging Mother Image by the hair or the feet down the worm-eaten staircase of terrified Syntax." (Léon Bloy, quoted in Robert Baldick, The Life of J.-K. Huysmans)

"It is difficult to find a writer whose vocabulary is so extensive, so constantly surprising, so sharp and yet so exquisitely gamey in flavour, so constantly lucky in its chance finds and in its very inventiveness." (Julien Gracq)

"In short, he kicks the oedipal to the curb" (M. Quaine, Heirs and Graces, 1932, Jowett / Arcana)

Huysmans' novel, Against the Grain, has more discussions of sound, smell and taste than any other work of literature we know of. For example, one chapter consists entirely of smell hallucinations so vivid that they exhaust the book's central character, Des Esseintes, a bizarre, depraved aristocrat. A student of the perfumer's art, Esseintes has developed several devices for titillating his jaded senses. Besides special instruments for re-creating any conceivable odour, he has constructed a special "mouth organ", designed to stimulate his palate rather than his ears. The organ's regular pipes have been replaced by rows of little barrels, each containing a different liqueur. In Esseintes's mind, the taste of each liqueur corresponded with the sound of a particular instrument.

"Dry curaçao, for instance, was like the clarinet with its shrill, velvety note: kümmel like the oboe, whose timbre is sonorous and nasal; crème de menthe and anisette like the flute, at one and the same time sweet and poignant, whining and soft. Then to complete the orchestra, comes kirsch, blowing a wild trumpet blast; gin and whisky, deafening the palate with their harsh outbursts of cornets and trombones:liqueur brandy, blaring with the overwhelming crash of the tubas."[14]

By careful and persistent experimentation, Esseintes learned to "execute on his tongue a succession of voiceless melodies; noiseless funeral marches, solemn and stately; could hear in his mouth solos of crème de menthe, duets of vespertro and rum." [15]

The protagonist of Submission (2015), a controversial novel by Michel Houellebecq, is a literary scholar specializing in Huysmans and his work; Huysmans's relation to Catholicism serves as a foil for the book's treatment of Islam in France.

Works by Huysmans

- Le drageoir aux épices (1874)

- Marthe (1876)

- Les Soeurs Vatard (1879)

- Sac au dos (1880)

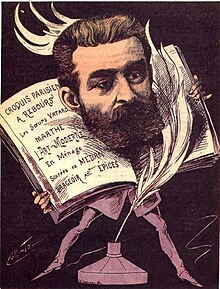

- Croquis Parisiens (1880, 2nd ed. 1886)

- En ménage (1881)

- Pierrot sceptique (1881, written in collaboration with Léon Hennique)

- À vau-l'eau (1882)

- L'art moderne (1883)

- À rebours (1884)

- En rade (1887)

- Un Dilemme (1887)

- Certains (1889)

- La bièvre (1890)

- Là-bas (1891)

- En route (1895)

- La cathédrale (1898)

- La Bièvre et Saint-Séverin (1898)

- La magie en Poitou. Gilles de Rais. (1899) (see Gilles de Rais)

- La Bièvre; Les Gobelins; Saint-Séverin (1901)

- Sainte Lydwine de Schiedam (1901, France) (on Saint Lydwine de Schiedam) (Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur)

- Saint Lydwine of Schiedam, translated from the French by Agnes Hastings (London, 1923, Kegan Paul)

- De Tout (1902)[16][17]

- Esquisse biographique sur Don Bosco (1902)

- L'Oblat (1903)

- Trois Primitifs (1905)

- Le Quartier Notre-Dame (1905)

- Les foules de Lourdes (1906)

- Trois Églises et trois Primitifs (1908)

Current editions :

- Écrits sur l’art (1867-1905), edited and introduced by Patrice Locmant, Paris, Éditions Bartillat, 2006.

- À Paris, edited and introduced by Patrice Locmant, Paris, Éditions Bartillat, 2005.

- Les Églises de Paris, edited and introduced by Patrice Locmant, Paris, Éditions de Paris, 2005.

- Le Drageoir aux épices, edited and introduced by Patrice Locmant, Paris, Honoré Champion, 2003.

- The Durtal Trilogy, edited by Joseph Saint-George with notes by Smithbridge Sharpe, Ex Fontibus, 2016 (Alternative site).

See also

- Léon Bloy

- Joseph-Antoine Boullan

- Stanislas de Guaita

- Henri Antoine Jules-Bois

- Joséphin Péladan

- Our Lady of La Salette

- Oscar Wilde

References

- ^ "Huysmans". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Twenty–three year–old Schopenhauer, who had a great influence on Huysmans, told Wieland, "Life is an unpleasant business. I have resolved to spend it reflecting on it. (Das Leben ist eine mißliche Sache. Ich habe mir vorgesetzt, es damit hinzubringen, über dasselbe nachzudenken.)" (Rüdiger Safranski, Schopenhauer and the Wild Years of Philosophy, Chapter 7).

- ^ Keeler, Sister Jerome (1950). "J.–K. Huysmans, Benedictine Oblate," American Benedictine Review, Vol. I, pp. 60–66.

- ^ The Cathedral, Introduction, Dedalus 1997

- ^ Satanism, Magic and Mysticism in Fin-de-siècle France, Robert Ziegler, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, pp. 2, 7, 125

- ^ The Mirror of Divinity: The World and Creation in J.-K. Huysmans, Robert Ziegler, University of Delaware Press, 2004, p. 159

- ^ Gollner, Adam. "What Houellebecq Learned from Huysmans". The New Yorker. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- ^ a b McClanahan, Clarence (2002). "Huysmans, Joris-Karl (1848–1907)". Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ^ a b Baldick, Robert (1959). Introduction to Against Nature, his translation of Huysmans' Á rebours. Harmondsworth: Penguin, p. 12.

- ^ Rudwin, Maxmilian J. (1920). "The Satanism of Huysmans," The Open Court, Vol. XXXIV, pp. 240–251.

- ^ Thurstan, Frederic (1928). "Huysmans' Excursion into Occultism," Occult Review, Vol. XLVIII, pp. 227–236.

- ^ Hanighan, F.C. (1931). "Huysmans Conversion," The Open Court, Vol. XLV, pp. 474–481.

- ^ Henry, Stuart (1897). Hours with Famous Parisians. Chicago: Way & Williams, p. 114.

- ^ Huysman, 1884/1931, p. 132

- ^ Sekuler, R., & Blake, R. (1985). Perception. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, pp. 404–405.

- ^ "Review of De Tout by J. K. Huysmans". The Athenæum (3903): 215. 16 August 1902.

- ^ Vivian, Herbert (26 July 1902). "The Genius of the Monastery: M. Huysmans at home". Black & White.

Further reading

- Addleshaw, S. (1931). "French Novel and the Catholic Church," Church Quarterly Review, Vol. CXII, pp. 65–87.

- Antosh, Ruth B. (1986). Reality and Illusion in the Novels of J-K Huysmans. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- Baldick, Robert (1955). The Life of J.-K. Huysmans. Oxford: Clarendon Press (new edition revised by Brendan King, Dedalus Books, 2006).

- Brandreth, H.R.T. (1963). Huysmans. London: Bowes & Bowes.

- Brian R. Banks (author) (1990). The Image of Huysmans. New York: AMS Press.

- Brian R. Banks (author) (2017) J.-K. Huysmans & the Belle Epoque: A Guided Tour of Paris. Paris, Deja Vu, introduction by Colin Wilson.

- Blunt, Hugh F. (1921). "J.K. Huysmans." In: Great Penitents. New York: The Macmillan Company, pp. 169–193.

- Brophy, Liam (1956). "J.–K. Huysmans, Aesthete Turned Ascetic," Irish Ecclesiastical Review, Vol. LXXXVI, pp. 43–51.

- Cevasco, George A. (1961). J.K. Huysmans in England and America: A Bibliographical Study. Charlottesville: The Bibliographical Society of the University of Virginia.

- Connolly, P.J. (1907). "The Trilogy of Joris Karl Huysmans," The Dublin Review, Vol. CXLI, pp. 255–271.

- Crawford, Virginia M. (1907). "Joris Karl Huysmans", The Catholic World, Vol. LXXXVI, pp. 177–188.

- Donato, Elisabeth M. (2001). Beyond the Paradox of the Nostalgic Modernist: Temporality in the Works of J.-K. Huysmans. New York: Peter Lang.

- Doumic, René (1899). "J.–K. Huysmans." In: Contemporary French Novelists. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, pp. 351–402.

- Ellis, Havelock (1915). "Huysmans." In: Affirmations. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, pp. 158–211.

- Garber, Frederick (1982). The Autonomy of the Self from Richardson to Huysmans. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- Highet, Gilbert (1957). "The Decadent." In: Talents and Geniuses. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 92–99.

- Huneker, James (1909). "The Pessimists' Progress: J.–K. Huysmans." In: Egoists. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, pp. 167–207.

- Huneker, James (1917). "The Opinions of J.–K. Huysmans." In: Unicorns. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, pp. 111–120.

- Kahn, Annette (1987). J.-K. Huysmans: Novelist Poet and Art Critic. Ann Arbor, Mich.: UMI Research Press.

- Laver, James (1954). The First Decadent: Being the Strange Life of J.K. Huysmans. London: Faber & Faber.

- Lavrin, Janko (1929). "Huysmans and Strindberg." In: Studies in European Literature. London: Constable & Co., pp. 118–130.

- Locmant, Patrice (2007). J.-K. Huysmans, le forçat de la vie. Paris: Bartillat (Goncourt Prize for Biography).

- Lloyd, Christopher (1990). J.-K. Huysmans and the fin-de-siecle Novel. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Mason, Redfern (1919). "Huysmans and the Boulevard," The Catholic World, Vol. CIX, pp. 360–367.

- Mourey, Gabriel (1897). "Joris Karl Huysmans," The Fortnightly Review, Vol. LXVII, pp. 409–423.

- Olivero, F. (1929). "J.–K. Huysmans as a Poet," The Poetry Review, Vol. XX, pp. 237–246.

- Peck, Harry T. (1898). "The Evolution of a Mystic." In: The Personal Equation. New York and London: Harper & Brothers, pp. 135–153.

- Ridge, George Ross (1968). Joris Karl Huysmans. New York: Twayne Publishers.

- Shuster, George N. (1921). "Joris Karl Huysmans: Egoist and Mystic," The Catholic World, Vol. CXIII, pp. 452–464.

- Symons, Arthur (1892). "J.–K. Huysmans," The Fortnightly Review, Vol. LVII, pp. 402–414.

- Symons, Arthur (1916). "Joris–Karl Huysmans." In: Figures of Several Centuries. London: Constable and Company, pp. 268–299.

- Thorold, Algar (1909). "Joris–Karl Huysmans." In: Six Masters of Disillusion. New York: E.P. Dutton & Company, pp. 80–96.

- Ziegler, Robert (2004). The Mirror of Divinity: The World and Creation in J.-K. Huysmans. Newark: University of Delaware Press.

External links

- Joris Karl Huysmans, website includes almost all of Huysmans' published work and contemporary material about him.

- Works by or about Joris-Karl Huysmans at the Internet Archive

- Petri Liukkonen. "Joris-Karl Huysmans". Books and Writers.

- Works by Joris-Karl Huysmans at Project Gutenberg

- Against The Grain by Joris-Karl Huysmans, Project Gutenberg ebook (Also known as Á Rebours or Against Nature)

- Là-bas (Down There) by J. K. Huysmans, Project Gutenberg ebook (Also known as The Damned)

- J. K. Huysmans, The Cathedral, Project Gutenberg ebook

- Works by Joris-Karl Huysmans at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Joris-Karl Huysmans, Catholic Encyclopedia

- 1848 births

- 1907 deaths

- Burials at Montparnasse Cemetery

- Officiers of the Légion d'honneur

- Converts to Roman Catholicism from atheism or agnosticism

- Deaths from oral cancer

- Decadent literature

- French art critics

- 19th-century French novelists

- 20th-century French novelists

- French people of Dutch descent

- French Roman Catholic writers

- Our Lady of La Salette

- Writers from Paris

- Benedictine oblates

- French male novelists