31 March incident

| History of the Ottoman Empire |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| Historiography (Ghaza, Decline) |

The 31 March Incident (Turkish: 31 Mart Vakası, 31 Mart Olayı, 31 Mart Hadisesi, or 31 Mart İsyanı) was the defeat of the Ottoman countercoup of 1909 by the Hareket Ordusu (Army of Action), which was the 11th Salonika Reserve Infantry Division of the Third Army stationed in the Balkans and commanded by Mahmud Shevket Pasha on 24 April 1909. The counter coup began on 31 March on the Rumi calendar, which was the official calendar of the Ottoman Empire, corresponding to 13 April 1909 on the Gregorian calendar now used in Turkey. The rebellion had begun on 13 April 1909 and was put down by 24 April 1909. Ottoman historiography link the two events under the name 31 March Incident but refers to the actions by the Hareket Ordusu, the subsequent restoration of the constitution for a third time (after earlier attempts in 1876 and 1908) and the deposition of Abdul Hamid II who was then replaced by his younger brother Mehmed V.

Background

The Young Turk Revolution, which began in the Balkan provinces, spread quickly throughout the empire and resulted in the Sultan Abdul Hamid II announcing the restoration of the Ottoman constitution of 1876 on 3 July 1908. The Ottoman general election of 1908 took place during November and December of that year. The Senate of the Ottoman Empire reconvened for the first time in over 30 years on 17 December 1908. The Chamber of Deputies' first session was on 30 January 1909. The Ottoman counter-coup of 13 April 1909 was a rebellion by conservative reactionaries in Constantinople against the restoration of the constitutional system. The counter-coup attempted to put an end to the nascent Second Constitutional Era in order to re-affirm the position of the Sultan Abdul Hamid II as the absolute monarch. The counter-coup, was instigated among some parts of the army primarily by a certain Cypriot Islamist[1] Dervish Vahdeti, who reigned supreme in Istanbul for a few days.

Events

The CUP appealed to Mahmud Shevket Pasha, commander of the Ottoman Third Army based in Selanik (modern Thessaloniki) to quell the uprising[2][3] by Dervish Vahdeti and his supporters. With support from the commander of the Ottoman Second Army in Edirne, Mahmud Shevket combined the armies to create a strike force named Hareket Ordusu ("Army of Action").[2][3] The Army of Action numbered 20,000-25,000 Ottoman troops[2] and were involved in events known as the 31 March Incident toward ending the coup.[4] The eleventh Reserve (Redif) Division based in Selanik composed the advance guard of the Action Army and the chief of staff was Mustafa Kemal Pasha.[3][5]

The Action Army were joined by 15,000 volunteers including 4,000 Bulgarians, 2,000 Greeks and 700 Jews.[2] Adding to those numbers were Albanians that supported the Action Army with Çerçiz Topulli and Bajram Curri bringing 8,000 Albanian men and Major Ahmed Niyazi Bey with 1,800 men from Resne.[6] In short time CUP members Fethi Okyar, Hafız Hakkı and Enver Bey returned from their international posts at Ottoman embassies and joined Mahmud Shevket as his military staff prior to reaching Istanbul.[7][3] Traveling by train the soldiers went to Çatalca, then Hademköy and later reached Ayastefanos (modern Yeşilköy) located on the edge of Istanbul.[3] A delegation was sent to Army headquarters by the Ottoman parliament that sought to stop it from taking Istanbul through force.[3] The Army of Action laid siege to Constantinople on 17 April 1909.

The Sultan remained in the Yildiz and had frequent conferences with Grand Vizier Tewfik Pasha who announced:

His Sublime Majesty awaits benevolently the arrival of the so called constitutional army. He has nothing to gain or fear since his Sublimity is for the Constitution and is its supreme guardian.[8]

Negotiations continued for six days. The negotiators were Rear Admiral Arif Hikmet Pasha, Emanuel Karasu Efendi (Carasso), Esad Pasha Toptani, Aram Efendi and Colonel Galip Bey (Pasiner). Finally, at the moment when the conflict showed signs of extending to the public, the Salonikan troops entered Istanbul.

On April 24 the occupation of Istanbul by the Action Army began in the early morning through military operations directed by Ali Pasha Kolonja, an Albanian, that retook the city with little resistance from the mutineers.[9][10] The barracks of Tașkışla and Taksim offered strong resistance and by four o'clock of the afternoon the remaining rebels surrendered.[10]

The Macedonian troops attacked the Taksim and Tashkishla barracks. There was fierce street fighting in the European quarter where the guard houses were held by the First Army Corps. There was heavy fire from troops in the Tashkishla barracks against the advancing troops. The barracks had to be shelled and almost destroyed by the artillery located on the heights above the barracks before the garrison surrendered after several hours fighting and heavy losses. Equally desperate was the defence of the Taksim barracks. The attack on the Taksim barracks was led by Enver Bey. After a short battle they gained control of the palace on 27 April.[11]

Sultan Abdul Hamid was deserted by most of his advisors. The parliament discussed the question as to whether he would be permitted to remain on the throne or be deposed or even be executed. Putting the Sultan to death was considered unwise as such a step might rouse a fanatical response and plunge the Empire into civil war. On the other hand, there were those who felt that after all that had happened it was impossible that the Parliament could ever again work with the Sultan.[12]

On April 27 the Assembly held a meeting behind closed doors under the presidency of Said Pasha. In order to remove the Sultan, a fatwa was needed.[13] So, a fatwa drawn up in the form of question and was given to scholars to answer and sign. A scholar by the name of Nuri Efendi was brought to sign the fatwa. Initially, Nuri Efendi was unsure whether three crimes raised in the question were carried out by Abdulhamid. He initially suggested that it would better to ask the Sultan to resign. It was insisted that Nuri Efendi sign the fatwa. However Nuri Efendi continued to refuse. Finally, Mustafa Asim Efendi convinced him and so the fatwa was signed by him and then it was signed by the newly appointed Sheikh ul Islam, Mehmed Ziyâeddin Efendi, legalising it.[13][14] The fatwa complete with the answer was now read to the assembled members:

If an imam of the Muslims tampers with and burns the sacred books.

If he appropriates public money.

If after killing imprisoning and exiling his subjects unjustly, he swears to amend his ways and then perjures himself.

If he causes civil war and bloodshed among his own people.

If it is shown that his country will gain peace by his removal and if it be considered by those who have power that this imam should abdicate or be deposed.

Is it lawful that one of these alternatives be adopted.

The answer is "Olur" (it is permissible).[15]

Then the Assembly unanimously voted that Abdul Hamid should be deposed.

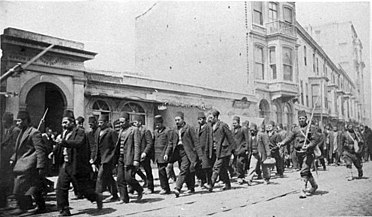

- 31 March Incident

-

Bakirkoy

-

Istanbul

-

Members of Counter-coup.

-

Taksim Military Barracks, where the counter-coup commenced.

-

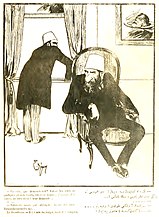

Delegation to Sultan Abdul Hamid II

-

Abdul Hamid II talking to his secretary shortly before he was forced to abdicate.

Outcome

The counter-coup's failure brought the Committee of Union and Progress back into power enabling it to form government.

The incident led to a change of Grand Vizier with Ahmed Tevfik Pasha assumed the position. Other consequences were restoration of constitution for a third time (after earlier attempts in 1876 and 1908). Both parliamentary chambers convened together on April 27 and deposed Abdul Hamid II.[9][2][10] He was replaced with his younger brother Reşat who took the name Mehmed V, to symbolically convey him as the second conquer of Istanbul after Mehmed II.[9][2][10] Four CUP members composed of one Armenian, one Jew and two Muslim Albanians went to inform the sultan of his dethronement, with Essad Pasha Toptani being the main messenger saying "the nation has deposed you".[2] Some Muslims expressed dismay that non Muslims had informed the sultan of his deposition.[2] As a result, the focus of the sultan's rage was toward Toptani whom Abdul Hamid II felt had betrayed him.[2] The sultan referred to him as a "wicked man", given that the extended Toptani family had benefited from royal patronage in gaining privileges and key positions in the Ottoman government.[2] Albanians involved in the counterrevolutionary movement were executed such as Halil Bey from Krajë which caused indignation among conservative Muslims of Shkodër.[9]

After the 31 March Incident, the Committee of Union and Progress outlawed societies which supported ethnic minorities' interests within Ottoman society, including the Society of Arab Ottoman Brotherhood, and prohibited the publication of several journals and newspapers that featured radical Islamic rhetoric.[citation needed]

Under the multi-religious "balancing policies", the Committee of Union and Progress believed it could achieve an "Ottomanisation" (i.e. Ottoman nationalism rather than ethnic or religious nationalism) of all the subjects of the Empire. These measures were successful in stirring some nationalist sentiment among the non-Turkish populations, further cementing a national sensibility resistant to conservative Islam.[citation needed]

Memorial

The Monument of Liberty (Ottoman Turkish: Abide-i Hürriyet) was erected 1911 in Şişli district of Istanbul as a memorial to the 74 soldiers killed in action during this event.

See also

References

- ^ Muammer Kaylan. The Kemalists: Islamic Revival and the Fate of Secular Turkey. Prometheus Books, Publishers. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-61592-897-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Gawrych 2006, p. 167.

- ^ a b c d e f Zürcher 2017, p. 202.

- ^ Zürcher 2017, pp. 200, 202.

- ^ Bardakci, Murat (16 April 2007). "Askerin siyasete yerleşmesi 31 Mart isyanıyla başladı". Sabah (in Turkish). Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- ^ Gawrych, George (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: IB Tauris. pp. 167–168. ISBN 9781845112875.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Yılmaz, Șuhnaz (2016). "Revisiting Netwrosk and Narratives: Enver Pasha's Pan-Islamic and Pan-Turkic Quest". In Moreau, Odile; Schaar, Stuart (eds.). Subversives and Mavericks in the Muslim Mediterranean: A Subaltern History. University of Texas Press. p. 144. ISBN 9781477310939.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Edward Frederick Knight, The Awakening of Turkey: A History of the Turkish Revolution, page 342

- ^ a b c d Skendi, Stavro (1967). The Albanian National Awakening. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 364–365. ISBN 9781400847761.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b c d Zürcher, Erik Jan (2017). "31 Mart: A Fundamentalist Uprising in Istanbul in April 1909?". In Lévy-Aksu, Noémi; Georgeon, François (eds.). The Young Turk Revolution and the Ottoman Empire: The Aftermath of 1918. I.B.Tauris. p. 203. ISBN 9781786720214.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Edward Frederick Knight, The Awakening of Turkey: A History of the Turkish Revolution, page 348

- ^ Edward Frederick Knight, The Awakening of Turkey: A History of the Turkish Revolution, page 350

- ^ a b Bardakçı, Murat (7 May 2008). "Osmanlı demokrasisi kitap yırttı diye padişahı bile tahtından indirmişti" (in Turkish). Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ KÜÇÜK, CEVDET (1988). "ABDÜLHAMİD II". İslâm Ansiklopedisi (in Turkish). TDV İslâm Araştırmaları Merkezi. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Edward Frederick Knight, The Awakening of Turkey: A History of the Turkish Revolution, page 351

External links

- Şeriatçı bir ayaklanma (A fundamentalist uprising) by Sina Akşin with particular emphasis on British involvement.