Murder of Michelle Martinko

Michelle Martinko | |

| Date | December 19, 1979 |

|---|---|

| Location | Westdale Mall, Cedar Rapids, Iowa |

| Coordinates | 41°57′07″N 91°43′12″W / 41.952°N 91.720°W |

| Target | Michelle Martinko |

| Convicted | Jerry Lynn Burns |

| Verdict | Guilty of first degree murder |

| Sentence | Life imprisonment without parole[1] |

The murder of Michelle Martinko occurred in Cedar Rapids, Iowa on December 19, 1979. It was a cold case until 2018, 39 years after the crime, when familial DNA identified her killer.[2]

Martinko, an eighteen year old high school student, was found stabbed to death in her family's car in the parking lot of a local mall where she had gone to buy a new coat. The murder was closely followed within her community, and the police received more than 200 tips in the weeks following her killing. However, the case gradually grew cold as the investigation stretched on. In 2006, a cold case investigator discovered unidentified blood, presumably belonging to the killer, while reviewing case files. A DNA profile was developed from this evidence and entered into the national Combined DNA Index System (CODIS), but no matches were found. In 2017, a company specializing in DNA phenotyping was hired to produce a new approximation of the killer's appearance based solely off the DNA sample. The following year, that company entered the DNA data from the case into the public genealogy website GEDmatch, where they found a familial DNA match. In October 2019, DNA was covertly collected from an Iowa man named Jerry Lynn Burns, and found to match the sample discovered on Martinko's clothing.[2][3][4] Burns was arrested, and on February 24, 2020 he was found guilty of first degree murder in the death of Michelle Martinko. On August 7, 2020, Burns was sentenced to life in prison without parole.[1][5][6]

Backgrounds

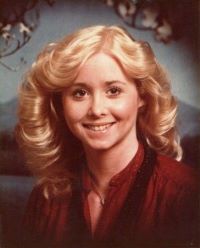

Michelle Martinko

Michelle Martinko | |

|---|---|

| Born | Michelle Marie Martinko October 6, 1961 Cedar Rapids, Iowa, U.S. |

| Died | December 19, 1979 (aged 18) Cedar Rapids, Iowa, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Stabbing |

| Resting place | Cedar Memorial Park Cemetery Cedar Rapids, Iowa, U.S. 42°01′23″N 91°38′02″W / 42.023°N 91.634°W |

Michelle Marie Martinko (October 6, 1961 – December 19, 1979) was born in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.[7] Martinko was the younger of two daughters of Albert F. Martinko and Janet Martinko (née Zillig).[8][9] She attended Cedar Rapids Kennedy High School, where she was an above average student and well regarded by school officials.[10][11] She was also a talented performer, joining the twirling squad as a sophomore and also performing in choirs and theater productions.[2] She did not have many close girlfriends or confidantes, which was speculated to be due to jealousy from other students over her beauty and stylish clothes,[11] or due to conflict over a boy she had dated.[12] Martinko, who was a senior in high school when she was killed, had plans to attend Iowa State University to study interior design.[2]

Jerry Lynn Burns

Jerry Lynn Burns (born 1953[13]) would have been 25 years old when he killed Michelle Martinko in December 1979. He grew up in Manchester, Iowa, and graduated from West Delaware High School in 1972. He was living in Manchester at the time of his arrest in 2020, and he owned a powder coating business in the city. Previously he had worked for John Deere and co-owned a truck stop. Burns had previously been married to Patricia Burns, who died in 2008 from suicide.[14] Burns' cousin, Brian Burns, went missing on December 19, 2013 and has not been found. Although Burns' arrest in the Martinko case raised questions about these two incidents, police do not believe Burns was involved in either.[15]

Murder and investigation

Murder

On the evening of December 19, 1979, Martinko attended a banquet for the Kennedy Concert Choir at the Sheraton Inn in Cedar Rapids.[10] She wore a black jersey dress and black scarf, black tights and heels, and a waist-length white and brown rabbit fur jacket, and she carried a brown leather purse.[9] After the event, she asked her friend and twirling squad teammate if she wanted to join her on a shopping trip to the Westdale Mall, which had recently opened, and where Martinko worked. Her friend declined, so Martinko went alone, carrying $180 and intending to purchase a new winter coat.[2] Once there, she perused the stores, speaking with friends and other people she knew who worked there.[9] She was last seen at 8 or 9 p.m. outside of a jewelry store in the mall.[2][16] At 2 a.m., Martinko had still not returned home, so her father reported her missing. He began to search for her, as did the police. At 4 a.m., police found the Martinko family's tan and green 1972 Buick Electra in the northeast corner of the mall parking lot by a JCPenney.[9] Martinko was found inside, collapsed over the passenger seat, stabbed to death.[2]

Martinko had been stabbed 29 times in her face, neck, and chest.[2][5] Her hands bore defensive wounds, which police said indicated she had fought back against her killer.[2] Police determined from the lack of blood outside the car that Martinko had been killed while in the car, and the medical examiner later estimated she had died between 8 and 10 p.m.[17] The murder weapon was "sharp-pointed", but not definitively a knife, and the medical examiner could not determine its size.[9] The killer left no fingerprints, which led police to believe they had worn gloves.[2] A police spokesman said that while "everyone's instinct is to say it was a guy", they were not sure of the gender of the killer.[16] Based on cash found in Martinko's purse, police concluded she had not been robbed.[9] She was fully dressed, and the medical examiner determined she had not been sexually assaulted.[10] Police considered the killing to be "personal in nature" based on the number and location of stab wounds.[9][2]

Initial investigation

Police had few leads, and appealed to the public for tips.[10] A police spokesman estimated that in the week after Martinko's murder, more than 200 people responded to the detectives' appeals in the news for information concerning the case. Police interviewed numerous people, and several were cleared of suspicion through use of a polygraph. A juvenile found carrying a knife was interviewed and ruled out in her murder, as was a shopping center employee who had told police that he enjoyed following women and ogling store mannequins. Rumors began to circulate about the crime. Some thought that Martinko had received harassing phone calls before her death; police stated that they did not think she had.[16] Another rumor emerged that a second stabbing had happened in the following days and that police were keeping it secret; police denied this.[18]

A man who had the month before broken into a Cedar Rapids home, raped a woman at knifepoint, and threatened to kill her children was a prime suspect in Martinko's murder for some time, but he was never charged. He denied the accusations, and DNA evidence found later was not a match. The man died in prison from colon cancer in 2012, where he was serving a life sentence for the unrelated attack.[18][19]

Controversy arose five months after the murder, when a woman who was driving by the mall parking lot in the early hours of December 20 came forward with information. She had looked into the parking lot as she drove by to check for her daughter's car, because her daughter worked at the mall and had had car trouble before. She claimed to have seen two cars in the lot, one of which was Martinko's, and a man standing next to the open driver's side door of Martinko's car. She wasn't sure her information would be of any use because she had read that the murder happened between 10 p.m. and midnight, and it was 2 a.m. when she drove by. The woman communicated her information to the daughter of the secretary of the Public Safety Commissioner, believing it would be passed on to police if it was important. The police never received the information, and the woman didn't contact police until months later when they reissued a call for any information connected to the murder. Detectives considered charging the Commissioner with failure to pass along the information to police, but no charges were pursued.[20]

On June 19, 1980, police released a composite sketch of a man believed to have killed Martinko, which they formed from descriptions provided by two witnesses under hypnosis.[11] They described a white man in his late teens or early 20s, around six feet tall and weighing 165–175 pounds, with brown eyes and curly brown hair.[11][18] In the year after the killing, the number of people interviewed by police reached the hundreds, and up to thirty people were interviewed under hypnosis.[11] As the investigation dwindled, a $10,000 reward was offered for information that would lead police to the killer.[21] Psychics were also consulted early on in the investigation.[11]

Cold case

As time went on the case grew cold.[4]

In the mid-1980s, Martinko's father filed a lawsuit against the owners of the Westdale Mall, claiming negligence in not providing "reasonable security" on the night of the murder. The case was appealed, and eventually decided by the Iowa Supreme Court in favor of the mall owners.[2]

Martinko's father Albert died in 1995; her mother Janet died in 1998.[2]

Resumption of investigation

In 2006, 27 years after Martinko's killing, a new cold case investigator working for the Cedar Rapids Police Department received a tip connected to the case. Although the tip did not lead to any suspects, the investigator discovered what he believed to be the killer's blood while he was reviewing the case files.[22][12] From this, police were able to build a partial DNA profile.[4] Documents concluded that fewer than one in 100 billion people would match the DNA profile. The results were entered into the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS), the national DNA database, but no matches were found.[7] Eventually, more than 125 people would have their DNA swabbed and compared against samples taken from the scene.[23] Out of more than 80 potential suspects that had been identified over the years, more than 60 people were tested and cleared of suspicion.[12]

In 2017, a company specializing in DNA phenotyping was hired to create additional images of the killer based solely on DNA clues about facial appearance and ancestry. The images looked considerably different from the 1980 composite sketch, showing a man with blond hair and blue eyes. The company also produced approximations of how the man would have aged in the years since the crime. In a press conference during which the new image was shared, a former classmate of Martinko's exclaimed that the face looked like another one of their classmates; however, that classmate had been investigated and was cleared based on a DNA swab several years before.[2] The police received more than 100 tips following the release of the new images.[24]

In 2018, the DNA phenotyping company took the data they had collected the year before and entered it into GEDmatch, a public genealogy website that has been used by law enforcement to solve other cold cases—most famously that of the Golden State Killer. GEDmatch returned one person who shared DNA markers with the suspect in Martinko's murder, and determined her to likely be the killer's second cousin once removed. The company created a family tree starting with four sets of the woman's great-great-grandparents, reporting that the killer was most likely descended from one of those couples. An investigator with the Cedar Rapids police department contacted and DNA tested members of two of the branches of the family tree, eliminating those branches as containing the killer. He then contacted a member of a third branch, and a DNA test determined that they were first cousins with the killer.[2] This narrowed the suspects down to a set of three brothers, who had grown up in Manchester, Iowa.[3] The brothers were placed under surveillance, and investigators began to attempt to secretly collect their DNA.[2]

Arrest and trial

On October 29, 2018, an investigator observed one of the brothers, Jerry Lynn Burns, drink multiple sodas using a plastic straw. When Burns disposed of the straw, the investigator collected it and tested it for DNA. DNA tests eliminated the other two brothers as suspects, but the DNA from Burns' straw matched the blood found on Martinko's clothing.[2][23] On December 19, 2018, investigators went to Burns' business in Manchester, Iowa to interview him.[25] He refused to voluntarily provide a sample of DNA, but was compelled to do so with a search warrant. His hands and arms were also examined for scars possibly left by the assumed cut sustained during the attack. Burns maintained that he did not know Martinko and was not there when she died, although an investigator later testified that Burns did not specifically deny killing Martinko.[26] He was not able to provide an explanation for why his DNA would have been present at the crime scene. According to the investigator, "Burns showed almost no emotion during the interview, even when he was eventually told he was being arrested."[2] When asked if he had killed someone that night in 1979, Burns repeatedly told investigators, "Test the DNA".[26] When the DNA sample was tested, it matched the blood sample found at the crime scene.[2]

Arrest and pretrial events

On December 19, 2018, exactly 39 years after Martinko's murder, Burns was arrested and charged with first-degree murder. He entered a plea of not guilty. His trial was originally scheduled for October 14, 2019, but in September the defense requested a delay in order to gather more evidence and interview witnesses. The defense also requested the trial be moved out of Linn County based on the amount of attention the case had received over the past four decades, as well as "pervasive and prejudicial pretrial publicity". The prosecution did not resist either request, and the trial was rescheduled for February 10, 2020 in Scott County.[2][4][27]

In pretrial hearings, Burns' attorneys claimed that police needed a search warrant to gather his DNA from the discarded straw, but the judge determined that discarded property cannot reasonably be considered private.[28] The defense also requested that evidence pertaining to Burns' cell phone browser history be suppressed. Investigators had reviewed Burns' 2018 internet searches and found that he regularly visited websites showing blonde women being raped, stabbed, and strangled, and which depicted sexual intercourse with murder victims.[29] The judge determined the search history was not usable in the trial due to the decades of time separating the murder and the searches.[28]

Trial

After two days of jury selection, the murder trial began on February 12, 2020. The prosecution emphasized the unlikelihood of the DNA evidence matching someone other than the person who left it at the scene.[30] The doctor who performed Martinko's autopsy and investigators in the original case, all now retired, took the stand to testify to how the investigation was conducted, and to Martinko's cause of death.[31] The defense argued that DNA evidence had been mishandled,[31] and that different articles of clothing from the scene should not have been stored together in one evidence bag.[32] Prosecutors also played a video of a police interview of Burns, in which he denied being at the crime scene on the night of Martinko's murder, and could not explain how his DNA had been found at the scene. They also played a later recording, after Burns' arrest, in which Burns questioned whether he could have blocked out the memory of committing the crime.[30]

The defense brought only one witness, a self-described forensic DNA consultant, who testified on the possibility that police could have mishandled the evidence. He stated that Burns' DNA could have been at the scene due to secondary transfer (such as skin cells transferring to an article of clothing when someone brushes up against another person), although he clarified that it was not his opinion that this was the case with Burns' DNA.[33] Prosecutors called a criminalist to contradict the defense's witness; the criminalist said that the storage of Martinko's clothing was not unusual.

Burns' defense team objected to the wording of one of the prosecution's questions, which they claimed implied unequivocally that Burns' blood had been at the scene. The prosecution requested the case be declared a mistrial as a result, but the judge denied the request and asked the prosecutor to rephrase the question.[34]

On February 24, 2020, after three hours of deliberation, the jury found Jerry Lynn Burns guilty of first degree murder of Michelle Martinko.[1][5] Burns is due to be sentenced in August and Iowan law mandates a life sentence without the possibility of parole for first degree murder.[35] On May 29, 2020, Burns' attorneys filed a motion asking for a new trial, claiming his constitutional and state rights were violated and that the court made a mistake in overruling the request for evidence to be suppressed.[36][37]

On August 7, 2020, Burns was sentenced to life in prison without parole.[6]

See also

Notes

References

- ^ a b c Spoerre, Anna (February 24, 2020). "'This is Michelle's day': Jury convicts Iowa man of first-degree murder in 1979 slaying of Cedar Rapids teen". Des Moines Register. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Moulton, Jen (October 2, 2019). "Michelle Martinko's murder 'haunted' the Cedar Rapids community for 40 years. Now, her suspected killer is set to go on trial". Little Village. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Mehaffey, Trish (March 12, 2019). "Search warrant shows how relative's DNA led police to Manchester man in Michelle Martinko's death". The Gazette. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d Spoerre, Anna (December 19, 2019). "40 years later: What we know about Michelle Martinko and the arrest that re-opened the cold case". Des Moines Register. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c Mehaffey, Trish (February 24, 2020). "Jerry Burns found guilty of first-degree murder in the death of Michelle Martinko". The Gazette. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "BREAKING: Jerry Burns, convicted of killing Michelle Martinko, officially sentenced to life in prison". KWWL. August 7, 2020. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Kurt, Dylan (December 26, 2018). "Cold case heats up". Manchester Press. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Janet Martinko". Quad-City Times. Davenport, Iowa. April 1, 1998. p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e f g Stevens, Nancy; Rogahn, Kurt (January 25, 1980). "New theory, plea in Martinko case". The Gazette. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d Rogahn, Kurt (December 20, 1979). "C.R. Student, 18, slain". The Gazette. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e f Rogahn, Kurt (June 19, 1980). "Hypnosis aids Martinko probe". The Gazette.

- ^ a b c "30 years ago: Murder of teen haunts those who knew her". The Gazette. December 20, 2009. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Mehaffey, Trish (March 22, 2019). "Distant relative learns her DNA led to arrest in Michelle Martinko slaying". The Gazette. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Saunders, Forrest (December 19, 2018). "Friends of man arrested in Martinko murder shocked". KCRG-TV. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Davis, Tyler J. (February 19, 2019). "Iowa community tries to reconcile a cold case arrest and its long history with a neighbor". Des Moines Register. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c Rogahn, Kurt (December 28, 1979). "New plea for murder clues". The Gazette.

- ^ Rogahn, Kurt (December 21, 1979). "C.R. police seek clues in murder of teen-ager". The Gazette.

- ^ a b c Rogahn, Kurt (December 19, 1980). "Year after C.R. slaying: No motive or clue". The Gazette.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Miller, Vanessa (January 17, 2012). "One-time suspect in unsolved Cedar Rapids homicide dies in prison". The Gazette. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Rogahn, Kurt (October 3, 1981). "Furor erupts in Martinko death probe". The Gazette.

- ^ Hogan, Dick; Rogahn, Kurt (April 21, 1980). "$10,000 Martinko reward". The Gazette.

- ^ "Cold Case Spotlight: Michelle Martinko". NBC News. December 28, 2014. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Nozicka, Luke (April 15, 2019). "Police collected DNA from dozens while investigating 1979 killing of Michelle Martinko". Des Moines Register. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "UPDATE: Tips coming into CRPD since Martinko press conference". KCRG-TV. September 12, 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Ivanisevic, Alex; Nozicka, Luke (December 20, 2018). "39 years later, man charged in cold-case killing of high school student Michelle Martinko". USA Today. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Payne, Kate (February 24, 2020). "Jury Finds Burns Guilty Of First Degree Murder In Killing Of Martinko". Iowa Public Radio. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Spoerre, Anna (December 10, 2019). "Trial for Jerry Burns, charged in the 1979 killing of 18-year-old Michelle Martinko, moved out of Linn County". Des Moines Register. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "No delay in trial for man accused of killing Michelle Martinko". KCRG-TV. February 7, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Tucker, Janelle (January 17, 2020). "Burns' Second Hearing Focuses on Pornography". KMCH. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "From the crime to conviction, a timeline of events in the murder of Michelle Martinko". KCRG. February 24, 2020. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Scheinblum, Aaron (February 13, 2020). "Witnesses describe murder scene in trial of man accused of killing Michelle Martinko in 1979". KCRG. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Scheinblum, Aaron (February 14, 2020). "Witnesses describe procedure in collecting, storing, and tracking evidence as part of cold-case murder trial". KCRG. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Scheinblum, Aaron (February 20, 2020). "Jerry Burns defense calls one witness, rests its case after testimony from self-defined forensic DNA consultant". KCRG. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Scheinblum, Aaron (February 21, 2020). "After denied mistrial motion, testimony in Michelle Martinko murder case concludes". KCRG. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Iowa man guilty in 1979 killing of high school student". The Associated Press. February 24, 2020. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Oates, Trevor (June 17, 2020). "Lawyers for Jerry Burns file motion for new trial". KWWL. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Moudy, Shannon (June 15, 2020). "Jerry Burns attorney files for new trial". KGAN. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

- 1961 births

- 1979 deaths

- 1979 in Iowa

- 1979 murders in the United States

- 21st century American trials

- Deaths by stabbing in Iowa

- December 1979 crimes

- December 1979 events in the United States

- Female murder victims

- History of Cedar Rapids, Iowa

- Incidents of violence against women

- Murder in Iowa

- Murder trials

- People murdered in Iowa

- Violence against women in the United States