The History of King Lear

The History of King Lear is an adaptation by Nahum Tate of William Shakespeare's King Lear. It first appeared in 1681, some seventy-five years after Shakespeare's version, and is believed to have replaced Shakespeare's version on the English stage in whole or in part until 1838.[1]

Unlike Shakespeare's tragedy, Tate's play has a happy ending, with Lear regaining his throne, Cordelia marrying Edgar, and Edgar joyfully declaring that "truth and virtue shall at last succeed." Regarded as a tragicomedy, the play has five acts, as does Shakespeare's, although the number of scenes is different, and the text is about eight hundred lines shorter than Shakespeare's. Many of Shakespeare's original lines are retained, or modified only slightly, but a significant portion of the text is entirely new, and much is omitted. The character of the Fool, for example, is absent.

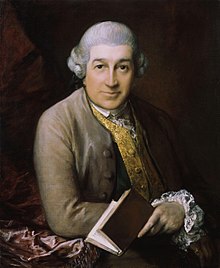

Although many critics – including Joseph Addison, August Wilhelm Schlegel, Charles Lamb, William Hazlitt, and Anna Jameson — condemned Tate's adaptation for what they saw as its cheap sentimentality, it was popular with theatregoers, and was approved by Samuel Johnson, who regarded Cordelia's death in Shakespeare's play as unbearable. Shakespeare's version continued to appear in printed editions of his works, but, according to numerous scholars, including A.C. Bradley and Stanley Wells, did not appear on the English stage for over a hundred and fifty years from the date of the first performance of Tate's play.[1][2][3] Actors such as Thomas Betterton, David Garrick, and John Philip Kemble, who were famous for the role of Lear, were portraying Tate's Lear, not Shakespeare's.

The tragic ending was briefly restored by Edmund Kean in 1823. In 1838, William Charles Macready purged the text entirely of Tate, in favour of a shortened version of Shakespeare's original. Finally, Samuel Phelps returned to the complete Shakespeare text in 1845.

Comparison with Shakespeare

Shakespeare's version

In Shakespeare's version, Lear, King of Britain, is growing old, and decides to divide his kingdom among his three daughters – Goneril, wife of the Duke of Albany, Regan, wife of the Duke of Cornwall, and the youngest daughter, Cordelia, sought in marriage by the Duke of Burgundy and the King of France. The King decides that he will give the best part of the kingdom to the daughter who loves him most, and asks his three daughters to state how much they love him. Goneril and Regan make hypocritical, flattering speeches, and are rewarded with a third each; Cordelia, however, cannot or will not stoop to false flattery for gain, and tells her father that she loves him as much as she should, and that she will love her husband as well if she marries. Enraged, the King disinherits and disowns his once-favourite child, and divides her portion between her two elder sisters. The loyal Earl of Kent speaks up boldly to defend Cordelia, and is banished by the furious King. The Duke of Burgundy withdraws his suit on finding Cordelia deprived of a dowry, but the King of France gladly accepts her as his bride.

In a sub-plot, the Earl of Gloucester is tricked by his wicked, illegitimate younger son, Edmund, into believing that his virtuous, legitimate elder son, Edgar is plotting his death. Edgar is forced to flee for his life, and disguises himself as a madman.

Kent, returning in disguise, offers himself in service to Lear, and is accepted. Lear also enjoys the loyalty of his Fool. Goneril and Regan, now that they have the kingdom, treat their father with contempt, and demand that he reduce the number of knights attending on him. Lear curses his daughters, and rushes out into the storm.

Gloucester tries to assist the King, despite being forbidden to by Regan and Cornwall. Edmund betrays his father, to inherit sooner. Regan and Cornwall interrogate Gloucester, and Cornwall gouges out Gloucester's eyes, before being killed by a horrified servant. Lear is raving in the storm with Kent and the Fool, his sanity gone. They are joined by Edgar, pretending to be mad. Edgar meets his blinded father. Grieved and shocked, he maintains his disguise but stays with his father and manages to save him from suicide.

Goneril and Regan both fall in love with Edmund and become jealous of each other. Edgar fights and kills a servant sent by Goneril to kill his father. He finds in the dead servant's pocket a letter from Goneril to Edmund, proposing that Edmund murder Albany and marry her. Cordelia meets Lear and they are reconciled. His frenzy has passed, and doctors are taking care of him.

Edgar, still disguised, gives Goneril's incriminating letter to Albany. An army, sent by Cordelia's forces in France, fights the British forces and is defeated. Lear and Cordelia are captured and sent to prison. Albany intends to show them mercy, but Edmund secretly sends a message to the prison to have them hanged. Edgar accuses Edmund of treachery, and challenges him to a duel. The two brothers fight, and Edmund is fatally wounded. Goneril rushes out in despair. Regan dies, and Goneril stabs herself to death, after confessing that she poisoned Regan. Edgar then reveals his identity to Edmund, and tells how their father died from frailty, joy, and grief, when Edgar revealed himself to him. Edmund expresses remorse, and confesses his order to have Lear and Cordelia hanged in prison. A reprieve is sent too late: Lear enters with Cordelia's body in his arms, howling in anguish. Kent tries to tell Lear how he served him in disguise, but Lear is unable to comprehend this, and has thoughts only for his dead daughter — "I might have saved her; now she's gone for ever." His heart breaks and he dies. Albany says that Kent and Edgar will rule in the Kingdom, but Kent hints at his own approaching death.

Tate's version

Tate's version omits the King of France, and adds a romance between Cordelia and Edgar, who never address each other in Shakespeare's original. Cordelia explains in an aside that her motive for remaining silent when Lear demands public expressions of love is that he leave her without a dowry, so she can escape the "loathed embraces" of Burgundy. Nevertheless, when Burgundy departs, his obvious self-interest temporarily causes her to lose faith in Edgar's love and fidelity, and, left alone with him, she tells him not to speak to her again of love.

There is no Fool in Tate's version, so Lear, left to his daughters' mercies, has the fidelity only of the disguised Kent. Cordelia never leaves for France, but stays in England and tries to find her father in the storm, to help him. Tate gives her a servant or confidant, Arante. Tate adds further wickedness to the character of Edmund, who plans to rape Cordelia, and sends two ruffians to abduct her. They are driven off by the disguised Edgar, who then reveals his identity to Cordelia, and is rewarded by being accepted back into her love again.

The battle to restore Lear to the throne is not from a foreign army sent by Cordelia, but from the British people, who are resentful of the tyranny of Goneril and Regan, indignant at their treatment of Lear, and outraged by the blinding of Gloster (changed in spelling from Shakespeare's original). As in Shakespeare's version, Lear's side loses, and he and Cordelia are taken prisoner. Edmund ignores Albany's wish to show mercy, and sends a secret message to have them hanged. Edgar reveals his identity to Edmund before the brothers fight. Edmund dies with no sign of remorse and makes no attempt to save Lear and Cordelia. Instead of Goneril poisoning Regan and later stabbing herself, the two sisters secretly poison each other. Gloster survives the shock of learning the identity of Edgar, whom he has treated unjustly. Lear kills two men who approach Cordelia to hang her, and Edgar and Albany arrive with a reprieve. Albany resigns the crown to Lear, and Lear announces that "Cordelia shall be Queen." Lear gives Cordelia to Edgar — "I wrong'd Him too, but here's the fair Amends." Lear, Kent, and Gloster will retire "to some cool Cell." The overjoyed Edgar declares that "Truth and Virtue shall at last succeed."

Tate's version is about 800 lines shorter than Shakespeare's.[4] Some of Shakespeare's original lines are left intact; some are modified slightly, or given to different speakers. In the words of Stanley Wells, Tate "rather asked for trouble by retaining as much of Shakespeare as he did, thereby inviting odious comparisons with verse that he wrote himself."[1] But Wells also points out that at the time that Tate was making his alterations, Shakespeare was not regarded as a master whose works could not be touched, but "as a dramatist whose works, however admirable, required adaptation to fit them for the new theatrical and social circumstances of the time, as well as to changes in taste."[4]

Many of the changes that are made by Tate are a result of Restoration ideas of the time. Tate's play was popular in the 1680s, after the restoring of the monarchy after the Interregnum. This time is known as the Restoration and there were specific tastes and ideas about theatre at this time due to the political and social climate which influenced the changes Tate made. James Black supports this claim by stating, "The Restoration stage was often an extension of the real-life political and philosophical milieu." Tate chose to draw upon politics and restore Lear to his throne just as Charles II was restored as the English monarch making the play more topical and relatable with audiences at the time. Not only can Tate's restoring Lear to the throne be justified by Restoration sensibilities but the addition of the love story between Cordelia and Edgar, and the omission of the Fool are also the result of Restoration ideas.

Background and history

The earliest known performance of Shakespeare's King Lear is one which took place at the court of King James I on 26 December 1606.[5] Some scholars believe that it was not well received, as there are few surviving references to it.[6] The theatres were closed during the Puritan Revolution, and while records from the period are incomplete, Shakespeare's Lear is only known to have been performed twice more, after the Restoration, before being replaced by Tate's version.[6]

Tate's radical adaptation — The History of King Lear — appeared in 1681. In the dedicatory epistle, he explains how in Shakespeare's version, he realised that he had found "a Heap of Jewels, unstrung and unpolisht; yet so dazling in their Disorder, that [he] soon perceiv'd [he] had seiz'd a Treasure", and how he found it necessary to "rectifie what was wanting in the Regularity and Probability of the Tale," a love between Edgar and Cordelia, which would make Cordelia's indifference to her father's anger more convincing in the first scene, and would justify Edgar's disguise, "making that a generous Design that was before a poor Shift to save his Life."[7]

The History of King Lear was first performed in 1681, in the Duke's Theatre in London, with the leading roles taken by Thomas Betterton (as Lear) and Elizabeth Barry (as Cordelia), both remembered now for their portrayal of Shakespeare's characters. Tate relates that he was "Rackt with no small Fears" because of the boldness of his undertaking, until he "found it well receiv'd by [his] Audience"[7]

This happy-ending adaptation was, in fact, so well received by audiences, that, according to Stanley Wells, Tate's version "supplanted Shakespeare's play in every performance given from 1681 to 1838", and was "one of the longest-lasting successes of the English drama."[1] As Samuel Johnson wrote, more than eighty years after the appearance of Tate's version, "In the present case the public has decided. Cordelia from the time of Tate has always retired with victory and felicity."[8] Famous Shakespearean actors such as David Garrick, John Philip Kemble, and Edmund Kean who played Lear during that period were not portraying the tragic figure who dies, broken-hearted, gazing at his daughter's body, but the Lear who regains his crown and gleefully announces to Kent:

- Why I have News that will recall thy Youth;

- Ha! Didst Thou hear 't, or did th' inspiring Gods

- Whisper to me Alone? Old Lear shall be

- A King again.

Although Shakespeare's entire text did not reappear on stage for over a century and a half, this does not mean that it was always completely replaced by Tate's version. Tate's version was itself subject to adaptation. It is known that Garrick used Tate's complete text in his performances in 1742, but playbills advertising performances at Lincoln's Inn Fields the following year (with an anonymous "Gentleman" playing Lear) mentioned "restorations from Shakespeare".[1] Garrick prepared a new adaptation of Tate's version for performances given from 1756, with considerable restoration from the earlier parts of the play, although Tate's happy ending was retained, and the Fool was still omitted.[1] Garrick's rival Spranger Barry also played Tate's Lear the same year, in a performance which, according to the poet and playwright Frances Brooke, moved the whole house to tears, though Brooke marvelled that Spranger and Garrick should both have given Tate's work "the preference to Shakespeare's excellent original", and that Garrick, in particular, should "prefer the adulterated cup of Tate to the pure genuine draught offered him by the master he avows to serve with such fervency of devotion."[9]

Although Garrick restored a considerable amount of Shakespeare's text in 1756, it was by no means a complete return to Shakespeare, and he continued to play Tate's Lear in some form to the end of his career. His performances met with enormous success, and continued to draw tears from his audiences, even without Shakespeare's final, tragic scene where Lear enters with Cordelia's body in his arms.[10]

As literary critics grew increasingly scornful of Tate, his version still remained "the starting point for performances on the English-speaking stage."[1] John Philip Kemble, in 1809, even dropped some of Garrick's earlier restorations of Shakespeare, and returned several passages to Tate.[10] The play was suppressed for several years prior to the death of King George III in 1820, as its focus on a mad king suggested an unfortunate resemblance to the situation of the reigning monarch.[11] But in 1823, Kemble's rival, Edmund Kean (who had previously acted Tate's Lear), "stimulated by Hazlitt's remonstrances and Charles Lamb's essays,"[2] became the first to restore the tragic ending, though much of Tate remained in the earlier acts. "The London audience," Kean told his wife, "have no notion of what I can do till they see me over the dead body of Cordelia."[12] Kean played the tragic Lear for a few performances. They were not well received, though one critic described his dying scene as "deeply affecting",[13] and with regret, he reverted to Tate.[10]

In 1834, William Charles Macready, who had previously called Tate's adaptation a "miserable debilitation and disfigurement of Shakespeare's sublime tragedy",[13] presented his first "restored" version of Shakespeare's text, though without the Fool.[14] Writing of his excessive nervousness, he relates that the audience appeared "interested and attentive" in the third act, and "broke out into loud applause" in the fourth and fifth acts.[15] Four years later, in 1838, he abandoned Tate altogether, and played Lear from a shortened and rearranged version of Shakespeare's text,[10] with which he was later to tour New York,[14] and which included the Fool and the tragic ending. The production was successful, and marked the end of Tate's reign in the English theatre, though it was not until 1845 that Samuel Phelps restored the complete, original Shakespearean text.[6]

In spite of Macready's visit to New York with his production of a restored Shakespeare version, Tate remained the standard version in the United States until 1875, when Edwin Booth became the first notable American actor to play Lear without Tate.[10] No subsequent production reverted to Tate,[6] except for occasional modern revivals as historical curiosities, such as that offered by the Riverside Shakespeare Company in March 1985 at The Shakespeare Center in New York City.[16]

Critical reception

While Tate's version proved extremely popular on the stage, the response of literary critics has generally been negative. An early example of approval from a critic is found in Charles Gildon's "Remarks on the Plays of Shakespeare" in 1710:

The King and Cordelia ought by no means to have dy'd, and therefore Mr Tate has very justly alter'd that particular, which must disgust the Reader and Audience to have Vertue and Piety meet so unjust a Reward. . . . We rejoice at the deaths of the Bastard and the two Sisters, as of Monsters in Nature under whom the very Earth must groan. And we see with horror and Indignation the Death of the King, Cordelia and Kent.[17]

The translator and author Thomas Cooke also gave Tate's version his blessing: in the introduction to his own play The Triumphs of Love and Honour (1731), he commented that Lear and Gloucester "are made sensible or their Errors, and are placed in a State of Tranquility and Ease agreeable to their Age and Condition . . . rejoicing in the Felicity of Edgar and Cordelia." Cooke added that he had "read many Sermons, but remember[ed] no one that contains so fine a Lesson of Morality as this Play."[18]

Samuel Johnson also approved of the happy ending, believing that the fact that Tate's version had so successfully supplanted Shakespeare's was evidence that Shakespeare's tragedy was simply unendurable. Taking the complete disappearance of the tragic ending from the stage as a sign that "the public [had] decided", he added:

And if my sensations could add anything to the general suffrage, I might relate that I was many years ago so shocked by Cordelia's death that I know not whether I ever endured to read again the last scenes of the play till I undertook to revise them as an editor.[19]

Others were less enthusiastic about the alterations. Joseph Addison complained that the play, as rewritten by Tate, had "lost half its beauty",[20] while August Wilhelm Schlegel wrote:

I must own, I cannot conceive what ideas of art and dramatic connexion those persons have who suppose that we can at pleasure tack a double conclusion to a tragedy; a melancholy one for hard-hearted spectators, and a happy one for souls of a softer mould. After surviving so many sufferings, Lear can only die, and what more truly tragic end for him than to die from grief for the death of Cordelia? and if he is also to be saved and to pass the remainder of his days in happiness, the whole loses its signification.[21]

In a letter to the editor of The Spectator in 1828, Charles Lamb expressed his "indignation at the sickly stuff interpolated by Tate in the genuine play of King Lear" and his disgust at "these blockheads" who believed that "the daughterly Cordelia must whimper [her] love affections before [she] could hope to touch the gentle hearts in the boxes."[22] Some years previously, Lamb had criticised Tate's alterations as "tamperings", and had complained that for Tate and his followers, Shakespeare's treatment of Lear's story:

- is too hard and stony; it must have love-scenes, and a happy ending. It is not enough that Cordelia is a daughter, she must shine as a lover too. Tate has put his hook in the nostrils of this Leviathan, for Garrick and his followers, the showmen of scene, to draw the mighty beast about more easily. A happy ending!—as if the living martyrdom that Lear had gone through,—the flaying of his feelings alive, did not make a fair dismissal from the stage of life the only decorous thing for him. If he is to live and be happy after, if he could sustain this world's burden after, why all this pudder and preparation,—why torment us with all this unnecessary sympathy? As if the childish pleasure of getting his gilt-robes and sceptre again could tempt him to act over again his misused station,—as if at his years, and with his experience, anything was left but to die.[23]

Quoting that extract from Lamb, and calling him "a better authority" than Johnson or Schlegel "on any subject in which poetry and feelings are concerned",[24] essayist William Hazlitt also rejected the happy ending, and argued that after seeing the afflictions that Lear has endured, we feel the truth of Kent's words as Lear's heart finally breaks:

- Vex not his ghost: O let him pass! he hates him

- That would upon the rack of this tough world

- Stretch him out longer.[25]

The art and literature critic Anna Jameson was particularly scathing in her criticism of Tate's efforts. In her book on Shakespeare's heroines, published just six years before Macready finally removed all traces of Tate from Shakespeare's play, Jameson wondered

who, after sufferings and tortures such as [Lear's], would wish to see his life prolonged? What! replace a sceptre in that shaking hand?—a crown upon that old grey head, on which the tempest had poured in its wrath, on which the deep dread-bolted thunders and the winged lightnings had spent their fury? O never, never![26]

Jameson was equally appalled by the introduction of a romance between Cordelia and Edgar, which had not been part of the old legend. While acknowledging that prior to Shakespeare's writing of King Lear, some versions of the story had ended happily, and that Tate's returning of the crown to Lear was therefore not a complete innovation, Jameson complained that on stage:

they have converted the seraph-like Cordelia into a puling love heroine, and sent her off victorious at the end of the play—exit with drums and colours flying—to be married to Edgar. Now anything more absurd, more discordant with all our previous impressions, and with the characters as unfolded to us, can hardly be imagined.[26]

The Shakespearean critic A.C. Bradley was more ambivalent. Though agreeing that we are right to "turn with disgust from Tate's sentimental adaptations, from his marriage of Edgar and Cordelia, and from that cheap moral which every one of Shakespeare's tragedies contradicts, 'that Truth and Virtue shall at last succeed'",[27] yet he "venture[d] to doubt" that "Tate and Dr. Johnson [were] altogether in the wrong".[2] Sharing Johnson's view that the tragic ending was too harsh, too shocking, Bradley observed that King Lear, while frequently described as Shakespeare's greatest work, the best of his plays, was yet less popular than Hamlet, Macbeth, and Othello; that the general reader, though acknowledging its greatness, would also speak of it with a certain distaste; and that it was the least often presented on stage, as well as being the least successful there.[28] Bradley suggested that the feeling which prompted Tate's alteration and which allowed it to replace Shakespeare on stage for over a century was a general wish that Lear and Cordelia might escape their doom. Distinguishing between the philanthropic sense, which also wishes other tragic figures to be saved, and the dramatic sense, which does not, but which still wishes to spare Lear and Cordelia, he suggested that the emotions have already been sufficiently stirred before their deaths, and he believed that Shakespeare would have given Lear "peace and happiness by Cordelia's fireside", had he taken the subject in hand a few years later, at the time that he was writing Cymbeline and The Winter's Tale.[29] Agreeing with Lamb that the agony that Lear has undergone makes "a fair dismissal from the stage of life the only decorous thing for him", Bradley argues that "it is precisely this fair dismissal which we desire for him", not the renewed anguish which Shakespeare inflicts on him with the death of Cordelia.[29]

As Tate's Lear disappeared from the stage (except when revived as a historical curiosity), and as critics were no longer faced with the difficulties of reconciling a happy ending on the stage with a tragic ending on the page, the expressions of indignation and disgust became less frequent, and Tate's version, when mentioned at all by modern critics, is usually mentioned simply as an interesting episode in the performance history of one of Shakespeare's greatest works.

Tate's Lear in the 20th and 21st centuries

Nahum Tate's The History of King Lear was successfully remounted in New York, at The Shakespeare Center on Mahattan's Upper West Side, staged by the Riverside Shakespeare Company in 1985.[30] For this production, conventions of the mid-17th-century English theatre, when Tate's Lear was popular, were used in the staging, such as raked stage covered with green felt (as was the custom for tragedies),[31] footlights used for illumination on an apron stage (or curved proscenium stage), and period costumes drawn from the era of David Garrick. Musical interludes were sung by cast members during the act breaks, accompanied by a harpsichord in the orchestra pit before the stage. The production was directed by the company's artistic director, W. Stuart McDowell, and featured Eric Hoffmann in the role of Lear, and supported by an Equity company of fifteen, including Frank Muller in the role of the Bastard Edmund.[32] The play, with its "happy ending", became known as a "King Lear for optimists" by the press, and proved one of the most popular productions by the Riverside Shakespeare Company.[31]

The play formed part of the American Shakespeare Center's 2013–2014 "Slightly Skewed Shakespeare" Staged Reading series, produced on 19 April 2014 by graduate students from Mary Baldwin College's Shakespeare and Performance MLitt/MFA program.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Stanley Wells, "Introduction" from King Lear, Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 63; Stanley Wells and Michael Dobson, eds., The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare Oxford University Press, 2001, p. 247; Grace Ioppolo, ed., King Lear, New York, Norton Critical Edition, 2008, Introduction, p. xii.

- ^ a b c A.C. Bradley, Shakespearean Tragedy, 1904. Reprinted by Macmillan 1976. Lecture VII, p. 199.

- ^ Bradley, Lecture VIII, p. 261.

- ^ a b Wells, p. 62.

- ^ Wells and Dobson, p. 247.

- ^ a b c d Charles Boyce, Encyclopaedia of Shakespeare, New York, Roundtable Press, 1990, p. 350.

- ^ a b Nahum Tate, The History of King Lear, Epistle Dedicatory.

- ^ Samuel Johnson on Shakespeare, London, Penguin Books, 1989, p. 222-3.

- ^ Frances Brooke, The Old Maid (1756), reprinted in Brian Vickers, ed. Shakespeare: The Critical Heritage Volume 4, London, Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1974, p. 249.

- ^ a b c d e Wells, p. 69.

- ^ Grace Ioppolo, William Shakespeare's King Lear: A Sourcebook. London, Routledge, 2003, p. 79.

- ^ Edward Dowden, "Introduction to King Lear" in Shakespeare Tragedies, Oxford University Press, 1912, p. 743.

- ^ a b George Daniel, quoted in Ioppolo, Sourcebook, p. 79.

- ^ a b Ioppolo, Sourcebook, p. 69.

- ^ Extracts from Macready's Reminiscences and Selections from his Diaries and Letters ed. F. Pollock, 1876, reproduced in Ioppolo, Sourcebook, p. 80.

- ^ Eleanor Blau, Lear with a Twist, The New York Times, 8 March 1985

- ^ Ioppolo, Sourcebook, p. 49.

- ^ Thomas Cooke, The Triumphs of Love and Honour (1731), reprinted in Brian Vickers, ed., Shakespeare: The Critical Heritage Volume 2, London, Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1974, p. 465-6.

- ^ Samuel Johnson on Shakespeare, p. 222-223.

- ^ Joseph Addison in The Spectator no. 40, 16 April 1711, quoted in Brian Vickers (ed) Shakespeare: The Critical Heritage Volume 2, London, Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1974, p. 273.

- ^ August Wilhelm Schlegel, Dramatic Art and Literature translated by John Black, London, Henry G. Bohn, 1846, p. 413.

- ^ Charles Lamb, "Shakespeare's Improvers", Letter to the Editor of The Spectator, 22 November 1828. Reprinted in Works of Charles and Mary Lamb, Volume 1, ed Thomas Hutchinson, Oxford University Press, 1908, pages 420–421.

- ^ Charles Lamb, On the Tragedies of Shakespeare.

- ^ William Hazlitt, Characters of Shakespear's Plays, 1817, reprinted London, Bell and Daldy, 1870, p. 124.

- ^ Act V, Scene 3, quoted in Hazlitt, p. 124.

- ^ a b Anna Jameson, Shakespeare's Heroines, 1832, reprinted London, G. Bell and Sons, 1913, p. 213.

- ^ Bradley, p. 205-206.

- ^ Bradley, pages 198–9.

- ^ a b Bradley, p. 206.

- ^ Eric Sven Ristad. "Excellent production of butchered King Lear." The Tech, Tuesday, 9 April 1985.

- ^ a b Howard Kissell, "King Lear for Optimists," Women's Wear Daily, 22 March 1985.

- ^ Mel Gussow, "Tate's Lear at Riverside," The New York Times, 5 April 1985.

External links

- Facsimile edition at the Horace Howard Furness Shakespeare Library

- Text of Tate's History of King Lear at Google Books

![]() The History of King Lear public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The History of King Lear public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Online version edited by Jack Lynch

- C.B. Hardman, Our drooping country now erects her head (Essay on Tate's Lear)