5th Missouri Infantry Regiment (Confederate)

| 5th Missouri Infantry Regiment | |

|---|---|

The Missouri Battle Flag | |

| Active | September 1, 1862 to October 6, 1863 |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | 618 (September 1, 1862) 276 (July 4, 1863) |

| Engagements | American Civil War |

The 5th Missouri Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment that served in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. The regiment entered into service on September 1, 1862, when the elements of two preceding battalions were combined. Many of the men entering the regiment had seen service with the secessionist Missouri State Guard. James McCown was the regiment's first colonel. After playing a minor role at the Battle of Iuka on September 19th, the regiment then fought in the Second Battle of Corinth on October 3rd and 4th. After being only lightly engaged on the 3rd, the regiment charged the Union lines on the 4th, capturing a fortification known as Battery Powell. However, Union reinforcements counterattacked and drove the regiment from the field. In early 1863, the regiment was transferred to Grand Gulf, Mississippi, where it built fortifications. The unit spent part of April operating in Louisiana, before again crossing the Mississippi River to return to Grand Gulf.

On May 1st, the regiment fought at the Battle of Port Gibson, where it and the 3rd Missouri Infantry Regiment charged the Union line in an attempt to turn the enemy's exposed flank. However, the two regiments missed hitting the Union line on the flank, and instead hit an area with greater support. After heavy fighting, the two regiments were forced to retreat. On May 16th, the regiment joined a large assault in the Battle of Champion Hill. The Confederate charge at Champion Hill captured two important battlefield features, but Union reinforcements and a lack of ammunition forced the men to retreat. After being routed at the Battle of Big Black River Bridge on May 17th, the regiment entered the defenses of Vicksburg, Mississippi. During the Siege of Vicksburg the regiment helped repel Union attacks on May 19th and 22nd. On June 25th and July 1st, the regiment opposed Union attempts to break the Confederate lines by detonating black powder beneath the Confederate defensive works. The Confederate garrison of Vicksburg surrendered on July 4th, and the men of the 5th Missouri Infantry were paroled. After being exchanged, the 5th Missouri Infantry was combined with the 3rd Missouri Infantry to form the 3rd and 5th Missouri Infantry Regiment (Consolidated); the 5th Missouri Infantry ceased to exist as a separate unit.

McCown retained command of the new unit after the consolidation. The consolidated regiment fought at the Battle of New Hope Church in May 1864, at the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain in June, and in the Siege of Atlanta. On October 5th, the regiment fought at the Battle of Allatoona before being nearly annihilated at the Battle of Franklin on November 30th. In February 1865, the regiment was transferred to Mobile, Alabama, where it surrendered during the Battle of Fort Blakely on April 9th, ending the men's combat career.

Background and formation

At the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, the state of Missouri did not secede, even though it was a slave state. However, Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson continued to push for secession and mobilized pro-secession elements of the state militia. The militiamen were encamped outside St. Louis, where a federal arsenal was located. In response, Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon of the Union Army dispersed the camp in the Camp Jackson affair on May 10th. This action was followed by a riot in St. Louis. On May 12th, Jackson formed the Missouri State Guard as a pro-secession militia unit and appointed Major General[a] Sterling Price, a veteran of the Mexican-American War, to command the unit. After a June 11th meeting between Price and Lyon indicated that a peaceful resolution to the turmoil was not possible, Lyon forced Jackson out of the state capital of Jefferson City on June 15th. After Lyon defeated a Missouri State Guard force at the Battle of Boonville on June 17th, Price and Jackson retreated into southwestern Missouri.[2]

Price was later reinforced by Confederate States Army troops commanded by Brigadier General Ben McCulloch. On August 10th, Lyon attacked the combined Confederate and Missouri State Guard troops. In the ensuing Battle of Wilson's Creek, Lyon was killed and his army defeated.[3] Afterwards, Price began moving northwards. This campaign culminated with the capture of Lexington in September. In October, Union forces began concentrating near where Price was encamped, leading the Missouri State Guard to retreat back to the southwestern portion of the state.[4] In November, Jackson and the pro-secession elements of the state legislature voted to secede, joining the Confederate States of America as a government-in-exile. The anti-secession elements of the state legislature had previously held a vote in July rejecting secession.[5] After Union forces began to threaten Price's position in southwestern Missouri in February 1862, the Missouri State Guard fell back to Arkansas, where it joined forces with Major General Earl Van Dorn.[6] Price himself entered Confederate service, receiving a commission as a major general.[1] In March, Van Dorn was defeated at the Battle of Pea Ridge, giving Union forces control of Missouri.[7] The men of the Missouri State Guard also began transferring to Confederate States Army units.[8]

The 5th Missouri Infantry Regiment became part of the Confederate States Army on September 1, 1862. To form the regiment, a portion of Hedgpeth's Missouri Battalion was combined with McCown's Missouri Battalion; a number of the men had formerly been part of the Missouri State Guard. James McCown was the regiment's first Colonel, Robert Bevier was the first lieutenant colonel, and Owen A. Waddell was appointed major. When the muster, which took place at Saltillo, Mississippi, was completed, 618 men were listed on the regiment's rolls.[9] As of the date of organization, the regiment contained ten companies, designated with the letters A–K and I; all were Missouri-raised.[9][b]

Service history

1862

After organizing, the regiment was designated the 5th Missouri Infantry Regiment despite the 6th Missouri Infantry Regiment having formed first.[11] After joining the First Missouri Brigade, the regiment saw light action at the Battle of Iuka on September 19, 1862, where it suffered five casualties. The regiment was next engaged at the Second Battle of Corinth on October 3rd and 4th.[11] At Second Corinth, the regiment was in Colonel Elijah Gates' brigade of Brigadier General Louis Hébert's division of the Confederate Army of West Tennessee.[12] On the first day at Corinth, Gates' brigade entered the action around 4:45 p.m., when it moved to aid Brigadier General Martin E. Green's brigade. However, Green ordered a charge after only one of Gates' regiments, the 2nd Missouri Infantry Regiment, had fully deployed.[13] The Confederate charge broke the Union outer line, but Price decided not to attack the interior Union lines on the night of the 3rd, instead choosing to wait for the next morning.[14]

On the morning of the 4th, Gates' brigade was part of a Confederate attack against the Union interior line; the attack was aimed at a fortification known as Battery Powell.[15] Much of the Union infantry broke and routed as the Confederate attack neared the Union position.[16] After reaching Battery Powell, the 5th Missouri Infantry fired a volley into the fortification, which cut down or dispersed the Union artillerymen still defending the position.[17] One Missourian later wrote that the inside of the fortification was "one of the bloodiest places [he] ever saw."[18] The colorbearer of the regiment was mortally wounded while crossing the wall of the works, and McCown was shot in the wrist.[19] Six of the regiment's company commanders had fallen during the attack.[20] Some of the men of the regiment turned captured cannons against the Union army.[21] As a whole, Gates' brigade was able to break a hole in the Union line that was 440 yards (400 m) long.[22] However, the Confederate attack was not supported, and the Union troops were able to regroup. The 5th Missouri Infantry was soon exposed to crossfire.[23] A Union counterattack eventually swept Gates' brigade, including the 5th Missouri Infantry, from the ground they had taken;[24] the regiment suffered 87 casualties over the course of the battle.[11] The regiment then spent the rest of 1862 encamped in northern Mississippi.[25]

1863

Louisiana expedition and Port Gibson

In March 1863, the regiment was transferred to Grand Gulf, Mississippi, where it built fortifications overlooking the Mississippi River.[25] In early April, the regiment was sent across the Mississippi River into Louisiana as part of a scouting force commanded by Colonel Francis M. Cockrell.[26] After arriving in Louisiana, the Missourians encamped near where Negro Bayou and Bayou Vidal connected.[27] Not long after arriving, the task force participated in two small actions near James' Plantation.[28] On April 15th, Company F was part of a small force Cockrell led in a surprise attack on a Union outpost at Dunbar's Plantation. While the Confederates captured the supplies at the outpost, the defenders of the outpost, elements of the 49th Indiana Infantry Regiment and the 120th Ohio Infantry Regiment, escaped.[29] On April 17th, the Missourians retreated back across the river into Mississippi, as the Union Navy had occupied New Carthage, Louisiana, threatening the security of the Confederate position.[30] After returning to Grand Gulf, the units of the First Missouri Brigade were given new battle flags. The flags bore a Latin cross on a blue background with a red trim.[31]

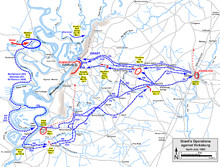

On April 30th, elements of the Union Army of the Tennessee commanded by Major General Ulysses S. Grant landed on the Mississippi side of the Mississippi River. Brigadier General John S. Bowen, Confederate commander at Grand Gulf, was tasked with delaying the Union advance at Port Gibson. The Confederate force at Port Gibson consisted of the troops of Green, Brigadier General William E. Baldwin, and Brigadier General Edward D. Tracy. Bowen sent the 3rd, 5th, and 6th Missouri Infantry Regiments, Guibor's Missouri Battery, and a portion of Landis' Missouri Battery to Port Gibson under the command of Cockrell.[32] Green's brigade was forced to retreat in the face of a Union attack, but a secondary line was formed from Baldwin's brigade, part of Cockrell's force, and the rallied survivors of Green's brigade. Meanwhile, the 6th Missouri Infantry was sent to the Confederate right, where Tracy had been killed.[33] The 3rd and 5th Missouri Infantry were kept as reserves for the early portion of the battle.[34] The combined strength of the two regiments was approximately 700[35] to 800 men.[36]

The two Missouri regiments were later sent to attempt to turn the exposed Union right flank. However, heavy trees and underbrush confused the Confederates, and the attack fell on the Union right-center, instead of the flank.[37] The Missourians came into view of the Union position at about 12:30 p.m.[36] After coming under Union artillery fire, the two Confederate regiments attacked the Union line, striking the brigades of Colonel James R. Slack and Brigadier General George F. McGinnis. The 3rd Missouri Infantry fought with McGinnis' brigade, and the 5th took on Slack's. The 5th Missouri Infantry had been aligned perpendicular to Slack's flank, and the regiment's attack broke through the line of two of Slack's regiments.[38] After advancing through the cover of a canebrake, the regiment attacked the 29th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment, which had little combat experience. The 29th Wisconsin Infantry suffered heavy casualties, but Union reinforcements arrived, driving the Confederates back into the cover of a ravine. Union troops pressed the Confederate position hard, with the lines sometimes only 10 feet (3.0 m) apart.[39]

Some of the men of the 5th Missouri Infantry left the ravine to attempt to outflank the 29th Wisconsin Infantry, which was part of the force attacking the regiment; the attempt was not successful. Eventually, Bowen ordered the 5th and 3rd Missouri Infantry to retreat. Seven men of Company I of the 5th volunteered to provide a rear guard in the ravine by pretending to be a much larger force; this was accomplished by firing rapidly and shouting fake orders.[40] The two regiments were able to escape from the field, and all seven men of the rear guard force escaped safely.[41] After returning to the main Confederate line, the two units also provided a rear guard for the main Confederate force as it slipped off the field.[42] The 5th Missouri Infantry reported 67 casualties at Port Gibson, and the 3rd Missouri Infantry 24,[43] although other estimates place the total loss of the two regiments as upwards of 200.[42]

Champion Hill

On May 7th, the regiment was reinforced when 100 exchanged prisoners joined the regiment, creating a second Company H.[25] The First Missouri Brigade was also issued .577 Enfield rifled muskets around the same time.[44] The regiment fought next on May 16th at the Battle of Champion Hill. Early in the battle, Company F was detached from the rest of the 5th Missouri Infantry as part of a battalion of skirmishers drawn from the infantry regiments of the First Missouri Brigade; the battalion was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Finley L. Hubbell of the 3rd Missouri Infantry.[45] By the early afternoon of the 16th, the Confederate left flank at Champion Hill was already collapsing. The First Missouri Brigade was sent by Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton to stabilize the Confederate line. The 5th Missouri Infantry was the first of the brigade's regiment to reach the front, where it formed next to the 56th Georgia Infantry Regiment.[46] The 3rd Missouri Infantry then formed next to the 5th. However, an attack by Slack's Union brigade routed the Georgians and captured Waddell's Alabama Battery. The two Missouri regiments were then exposed to enfilade fire, causing them to retreat slightly.[47] The rest of Cockrell's First Missouri Brigade arrived, and the 3rd and 5th Missouri Infantry moved back to their original positions. After full deployment, the brigade was aligned with the 6th Missouri Infantry and the 2nd Missouri Infantry on the left, the 3rd Missouri Infantry in the center, and the 5th Missouri Infantry and the 1st and 4th Missouri Infantry Regiment (Consolidated) on the right.[48]

Green's brigade formed to the right of Cockrell's brigade, and the two brigades charged, supported by fire from Landis' Battery and Lowe's Missouri Battery.[49] The Confederate charge broke the first Union line, and recaptured a strategic crossroads as well as the cannons of Waddell's Battery. After retaking the crossroads, the Confederates began advancing towards Champion Hill, another prominent battlefield feature. Cockrell's brigade defeated McGinnis' brigade, and Green's swept aside Slack's.[50] Union division commander Brigadier General Alvin P. Hovey ordered artillery batteries to support the Union line, including the 16th Ohio Battery, which inflicted heavy casualties on the Missourians with canister fire.[51] During the attack, the two lines were sometimes as close as 15 yards (14 m) apart.[52] After the attack had begun, newly rallied Confederate units, including the 56th Georgia Infantry and the 57th Georgia Infantry Regiments joined the attack.[53]

Union reinforcements arrived in the form of Colonels George B. Boomer's and John B. Sanborn's brigades.[54] The 5th Iowa Infantry Regiment was routed by the Confederates, but the Union reinforcements were enough to slow the momentum of the Confederate attack.[55] Most of the Confederates were halted, although the 1st and 4th Missouri Infantry (Consolidated) and portions of the 5th continued on in an attack, aiming for the Union supply train. However, the attack was unsuccessful.[56] Another Union brigade, commanded by Colonel Samuel A. Holmes, entered the fighting, and the Confederates were forced to withdraw.[57] The Confederates had also begun to run low on ammunition, as a Confederate officer, likely Major General Carter L. Stevenson, had ordered Cockrell's and Green's supply trains from the field.[58] Fire from Guibor's Battery, Landis' Battery, and Wade's Missouri Battery helped cover the retreat.[59] As Pemberton's Confederate army slipped from the field in retreat, the First Missouri Brigade was used as a rear guard.[60] The 5th Missouri Infantry lost 90 men at Champion Hill.[25][59]

Big Black River Bridge and the Siege of Vicksburg

On May 17th, Cockrell's brigade was part of a force defending the crossing of the Big Black River. It was on the Confederate right, between a body of water named Gin Lake and Brigadier General John C. Vaughn's brigade.[61] The 5th Missouri Infantry was positioned to the right of the 4th Mississippi Infantry Regiment. While the 5th Missouri Infantry repulsed a Union probing attack, a Union charge quickly routed Vaughn's brigade, exposing the flanks of the rest of the Confederate line. The Missourians were unaware that Vaughn's line had broken, and were surprised to receive orders to retreat. After the 4th Mississippi Infantry routed, the 5th Missouri Infantry was in a very exposed position and also routed, with the men racing across the river crossing.[62] After the defeat at Big Black River Bridge, the 5th Missouri Infantry entered the defenses of Vicksburg, Mississippi, where it was part of the Confederate reserve.[25] On May 19th, Grant's Union army made a major attack against the Vicksburg defenses. The 5th Missouri Infantry and the 1st and 4th Missouri Infantry (Consolidated) were sent to support a point known as the Stockade Redan, which was defended by the 36th Mississippi Infantry Regiment.[63] The two Missouri regiments drove back the attacking Union soldiers after an encounter Bevier described as a "sharp conflict" and "dreadful slaughter".[64] After the Union attacks were repulsed, most of Cockrell's brigade returned to reserve duty, although the 5th Missouri Infantry and the 1st and 4th Missouri Infantry (Consolidated) remained on the front line.[65]

Another Union assault took place on May 22nd. At the beginning of the charge, the 5th Missouri Infantry was occupying trenches south of the Stockade Redan.[66] A Union artillery barrage damaged the Confederate defenses, sending fragments of the wooden logs used to build the fortifications flying as shrapnel.[67] Union troops attacking the position of the 5th Missouri Infantry suffered heavy casualties, and some, including elements of the 6th and the 8th Missouri Infantry Regiments, became trapped in a ditch in front of the Confederate lines. During the fighting, some of the Missourians used artillery shells as homemade hand grenades.[68] After May 22nd, the 5th Missouri Infantry was regularly split into two groups: one held behind as a reserve, and the other manning the front line. By May 24th, the Union lines had grown so close to the Confederate lines that men of opposite sides could talk to each other.[69]

On May 27th, the regiment was shifted to another point in the Confederate line, and was again moved on May 28th, this time to a reserve position near a munitions storage site.[70] By early June, the Confederate defenders of Vicksburg were running low on percussion caps, hindering their ability to fire at their besiegers.[71] Rations began to run low, and the Missourians were forced to eat bread made out of animal fodder that one soldier claimed "might have knocked down a full-grown steer."[72] On June 25th, a tunnel filled with 2,200 pounds (1,000 kg) of black powder was exploded below a point in the Confederate line known as the Third Louisiana Redan. A gap was blown in the Confederate line, and Union infantry, led by the 45th Illinois Infantry Regiment, charged into the gap. The 5th and 6th Missouri Infantry were sent to the aid of the 3rd Louisiana Infantry Regiment, and the line stabilized.[73] Union troops filled the crater created by the explosion. Again, the Confederates used artillery shells as grenades, while Union troops countered with Ketchum grenades.[74] June 26th brought more fighting at the crater site, and more use of artillery shells as hand grenades.[75] By June 27th, the fighting around the crater had ended, although the sector was still considered one of the more dangerous points in the line. The 5th and 6th Missouri Infantry took turns defending the sector, with the 5th Missouri Infantry defending the line between midnight and 6:00 a.m. and between noon and 6:00 p.m. each day.[76] On July 1st, another tunnel beneath the Confederate line was detonated.[77] The 1,800 pounds (820 kg) of powder in this mine blew many Missourians into the air, including Cockrell.[78] However, no Union charge followed this explosion.[77]

On July 4th, the Confederate garrison at Vicksburg surrendered. By this point, only 276 men remained in the regiment.[77] The survivors of the 5th Missouri Infantry were paroled, sent to Demopolis, Alabama, and eventually exchanged. On October 6th, the 5th Missouri Infantry was consolidated into four companies, which were later combined with the survivors of the 3rd Missouri Infantry to form the 3rd and 5th Missouri Infantry Regiment (Consolidated). The 5th Missouri Infantry ceased to exist as a separate unit after the consolidation.[77]

Legacy

McCown was appointed colonel of the consolidated regiment, Waddell retained his rank of major, and Bevier was transferred to Richmond, Virginia to perform recruiting duty.[79] Companies A, C, F, and G of the new regiment contained men from the 5th Missouri Infantry, and Companies B, D, E, and H contained men from the 3rd.[80] On October 16, 1863, the 3rd and 5th Missouri Infantry (Consolidated) transferred to Meridian, Mississippi before moving to Mobile, Alabama in January 1864. After being stationed at Meridian, Demopolis, and various locations in northern Alabama, the regiment entered Georgia in May. By that point, only 340 men remained in the consolidated regiment. In May, the regiment fought at the Battle of New Hope Church before fighting at the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain in June. Later, the regiment defended Atlanta, Georgia during the Siege of Atlanta before abandoning the city in September. The 3rd and 5th Missouri Infantry (Consolidated) lost 123 men during the Atlanta Campaign. On October 5th, the regiment was part of a Confederate attack against a Union outpost in the Battle of Allatoona, a fight which cost the regiment 76 casualties. On November 30th, the consolidated regiment was nearly annihilated at the Battle of Franklin, losing 113 out of approximately 150 men. In February 1865, the regiment transferred to Mobile, where it surrendered on April 9th during the Battle of Fort Blakely, ending the men's combat experience.[81]

Notes

- ^ State militia rank.[1]

- ^ A second Company H was later created from an influx of exchanged prisoners.[10]

References

- ^ a b Wright 2013, p. 480.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 20–23.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 23–25.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 20, 25.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 34–37.

- ^ Gottschalk 1991, pp. 120.

- ^ a b McGhee 2008, pp. 202–203.

- ^ McGhee 2008, pp. 203–204.

- ^ a b c McGhee 2008, p. 203.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, p. 327.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, p. 210.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, pp. 237, 240.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, pp. 241–242.

- ^ Tucker 1995, p. 78.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, p. 243.

- ^ Tucker 1995, p. 79.

- ^ Tucker 1995, p. 80.

- ^ Tucker 1995, p. 82.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, pp. 244–245.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, p. 245.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, pp. 246–247.

- ^ a b c d e McGhee 2008, p. 204.

- ^ Tucker 1993, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Tucker 1993, p. 110.

- ^ Tucker 1993, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Tucker 1993, pp. 114–116.

- ^ Tucker 1993, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Tucker 1993, p. 122.

- ^ Tucker 1993, pp. 126, 128.

- ^ Tucker 1993, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Tucker 1993, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Tucker 1993, p. 138.

- ^ a b Gottschalk 1991, p. 220.

- ^ Tucker 1993, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Tucker 1993, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Tucker 1993, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Tucker 1993, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Tucker 1993, pp. 141–142.

- ^ a b Tucker 1993, p. 142.

- ^ McGhee 2008, pp. 195, 204.

- ^ Tucker 1993, p. 153.

- ^ Tucker 1993, pp. 156–158.

- ^ Tucker 1993, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Smith 2012, pp. 238–239.

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 239.

- ^ Smith 2012, pp. 240–241.

- ^ Tucker 1993, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Tucker 1993, p. 166.

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 251.

- ^ Smith 2012, pp. 261–262.

- ^ Smith 2012, pp. 266–271.

- ^ Smith 2012, pp. 274–276.

- ^ Tucker 1993, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Tucker 1993, pp. 173–174.

- ^ Smith 2012, pp. 283–284.

- ^ a b Tucker 1993, p. 175.

- ^ Tucker 1993, p. 176.

- ^ Ballard 2004, pp. 310–311.

- ^ Tucker 1995, pp. 208–211.

- ^ Tucker 1993, p. 185.

- ^ Gottschalk 1991, pp. 281–282.

- ^ Tucker 1993, p. 188.

- ^ Tucker 1993, p. 189.

- ^ Tucker 1995, p. 223.

- ^ Tucker 1995, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Tucker 1995, p. 226.

- ^ Tucker 1995, p. 228.

- ^ Tucker 1995, p. 229.

- ^ Tucker 1995, p. 232.

- ^ Tucker 1995, pp. 235–237.

- ^ Tucker 1995, pp. 237–238.

- ^ Tucker 1995, pp. 238–239.

- ^ Tucker 1995, pp. 239–240.

- ^ a b c d McGhee 2008, p. 205.

- ^ Tucker 1995, pp. 244–245.

- ^ McGhee 2008, pp. 197, 202.

- ^ McGhee 2008, p. 197.

- ^ McGhee 2008, pp. 197–199.

Sources

- Ballard, Michael B. (2004). Vicksburg: The Campaign that Opened the Mississippi. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2893-9.

- Cozzens, Peter (1997). The Darkest Days of the War: The Battles of Iuka and Corinth. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2320-1.

- Gottschalk, Phil (1991). In Deadly Earnest: The Missouri Brigade. Columbia, Missouri: Missouri River Press. ISBN 0-9631136-1-5.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- McGhee, James E. (2008). Guide to Missouri Confederate Regiments, 1861–1865. Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 978-1-55728-870-7.

- Smith, Timothy B. (2012). Champion Hill: Decisive Battle for Vicksburg (1st paperback ed.). El Dorado Hills, California: Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-932714-19-7.

- Tucker, Phillip Thomas (1993). The South's Finest: The First Missouri Confederate Brigade From Pea Ridge to Vicksburg. Shippensburg, Pennsylvania: White Mane Publishing Co. ISBN 0-942597-31-1.

- Tucker, Phillip Thomas (1995). Westerners in Gray: The Men and Missions of the Elite Fifth Missouri Infantry Regiment. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-3112-0.

- Wright, John D. (2013). The Routledge Encyclopedia of Civil War Biographies. New York, New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-87803-6.