Lynching of Paul Jones

| Part of Red Summer | |

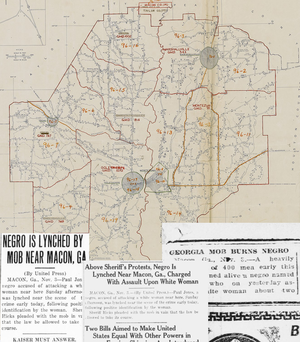

National news coverage of the Paul Jones lynching | |

| Date | November 2, 1919 |

|---|---|

| Location | Macon, Georgia |

| Participants | White mob in Macon, Georgia |

| Deaths | 1 |

Paul Jones[a] was lynched on November 2, 1919, after being accused of attacking a fifty-year-old white woman in Macon, Georgia.

Lynching of Paul Jones

On Sunday, November 2, 1919, Paul Jones allegedly attacked a white woman about 2 miles (3.2 km) outside of Macon.[2] Paul Jones was chased through town until he was cornered in a rail boxcar, there the woman positively identified him.[3] A white mob of 400 people quickly assembled and over the protests of Sheriff James R. Hicks they seized Jones. His body was riddled with bullets after being lynched, [4] "saturated with coal oil" and lit on fire.[5] He was still alive as the flames consumed his body and the mob watched as he writhed in pain.[1] There were no arrests.

Aftermath

These race riots were one of several incidents of civil unrest that began in the so-called American Red Summer of 1919, which included terrorist attacks on black communities and white oppression in over three dozen cities and counties. In most cases, white mobs attacked African American neighborhoods. In some cases, black community groups resisted the attacks, especially in Chicago and Washington DC. Most deaths occurred in rural areas during events like the Elaine Race Riot in Arkansas, where an estimated 100 to 240 black people and 5 white people were killed. Also in 1919 were the Chicago Race Riot and Washington D.C. race riot which killed 38 and 39 people respectively. Both had many more non-fatal injuries and extensive property damage reaching into the millions of dollars.[6]

See also

- Jenkins County, Georgia, riot of 1919

- Lynching of Berry Washington in Milan, Georgia

- Putnam County, Georgia, arson attack

Bibliography

Notes

- ^ a b McWhirter 2011, p. 241.

- ^ Palatka Daily News 1919, p. 1.

- ^ Greeneville Daily Sun 1919, p. 1.

- ^ The report of victium being lynched and shot appeared in an African-American newspaper "The Chicago Whip" November 15, 1919 page 1. Interestingly the report of the victium lynched in a railroad yard could help identify a lynching postcard on an unknown man taken in a Georgia railroad yard. See "Without Santuary" website photograph collection picture number # 12

- ^ The Daily Times 1919, p. 3.

- ^ The New York Times 1919.

References

- The Daily Times (November 3, 1919). "Georgia Mob Burns Negro". The Daily Times. Wilson, North Carolina: P.D. Gold Pub. Co. pp. 1–6. ISSN 2472-2847. OCLC 25415974. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Greeneville Daily Sun (November 3, 1919). "Above Sheriff's Protests, Negro Is Lynched Near Macon, Ga., Charged With Assault Upon White Woman". Greeneville Daily Sun. Greeneville, Greene, Tennessee: W.R. Lyon. pp. 1–4. ISSN 2475-0174. OCLC 37307396. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McWhirter, Cameron (2011). Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 9781429972932.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Total pages: 368 - The New York Times (October 5, 1919). "For Action on Race Riot Peril". The New York Times. New York, NY: Adolph Ochs. ISSN 1553-8095. OCLC 1645522. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Palatka Daily News (November 3, 1919). "Negro is lynched by mob near Macon, Ga". Palatka Daily News. Palatka, Putnam, Florida: Vickers & Guerry. pp. 1–6. ISSN 0163-5050. OCLC 4402148. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- 1919 deaths

- 1919 murders in the United States

- Deaths by firearm in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Lynching deaths in Georgia (U.S. state)

- People murdered in Georgia (U.S. state)

- 1919 crimes in the United States

- 1919 in Georgia (U.S. state)

- 1919 riots in the United States

- November 1919 events

- African-American history of Georgia (U.S. state)

- Arson in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Riots and civil disorder in Georgia (U.S. state)

- White American riots in the United States

- Racially motivated violence against African Americans

- Red Summer

- History of Georgia (U.S. state)

- Attacks on African-American churches