Gestational pemphigoid

| Gestational pemphigoid | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Pemphigoid gestationis |

| |

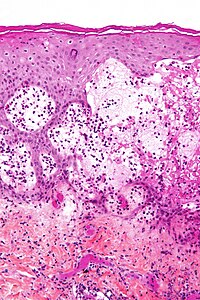

| Micrograph of gestational pemphigoid showing the characteristic subepidermal blisters and abundant eosinophils. HPS stain. | |

| Specialty | Obstetrics |

Gestational pemphigoid (GP) is an autoimmune blistering skin disease of pregnancy,[1][2][3] typically occurring in the second or third trimester. It was originally called herpes gestationis because of the blistering appearance, although it is not associated with the herpes virus. It is one of the pemphigoid (pemphigus-like) diseases.

Presentation

Diagnosis of GP becomes clear when skin lesions progress to tense blisters during the second or third trimester. The face and mucous membranes are usually spared. GP typically starts as a blistering rash in the navel area and then spreads over the entire body. It is sometimes accompanied by raised, hot, painful welts called plaques. After one to two weeks, large, tense blisters typically develop on the red plaques, containing clear or blood-stained fluid.[4] GP creates a histamine response that causes extreme relentless itching (pruritus). GP is characterized by flaring and remission during the gestational and sometimes post partum period. Usually after delivery, lesions will heal within months, but may reoccur during menstruation.[citation needed]

Causes

Pathogenically, it is a type II hypersensitivity reaction where circulating complement-fixing IgG antibodies bind to an antigen (a 180-kDa protein, BP-180) in the hemidesmosomes (attach basal cells of epidermis to the basal lamina and hence to dermis) of the dermoepidermal junction[further explanation needed], leading to blister formation as loss of hemidesmosomes causes the epidermis to separate from dermis. The immune response is even more highly restricted to the NC16A domain. The primary site of autoimmunity seems not to be the skin, but the placenta, as antibodies bind not only to the basement membrane zone of the epidermis, but also to that of chorionic and amniotic epithelia. Aberrant expression of MHC class II molecules on the chorionic villi suggests an allogenic immune reaction to a placental matrix antigen, thought to be of paternal origin. Recently, both IgA22 and IgE24 antibodies to either BP180 or BP230 have also been detected in pemphigoid gestationis.[citation needed]

Risk

Pregnant women with GP should be monitored for conditions that may affect the fetus, including, but not limited to, low or decreasing volume of amniotic fluid, preterm labor, and intrauterine growth retardation. Onset of GP in the first or second trimester and presence of blisters may lead to adverse pregnancy outcomes including decreased gestational age at delivery, preterm birth, and low birth weight children. Such pregnancies should be considered high risk and appropriate obstetric care should be provided. Systemic corticosteroid treatment, in contrast, does not substantially affect pregnancy outcomes, and its use for GP in pregnant women is justified.[5] GP typically reoccurs in subsequent pregnancies.[6] Passive transfer of the mother’s antibodies to the fetus causes some (about 10%) newborns to develop mild skin lesions, but these typically will resolve within weeks of parturition.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis

GP often is confused with pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP), especially if it occurs in a first pregnancy. PUPPP typically begins in stretch mark areas of the abdomen and usually ends within two weeks after delivery. PUPPP is not an autoimmune disease.[citation needed]

Diagnosing GP is done by biopsy using direct immunofluorescence, appearance, and blood studies.[7]

Treatment

The most accepted way to treat GP is with the use of corticosteroids,[8] i.e. prednisone; and/or topical steroids, i.e. clobetasol and betamethasone. Suppressing the immune system with corticosteroids helps by decreasing the number of antibodies attacking the skin. Treating GP can be difficult and can take several months. Some cases of GP persist for many years. In the post partum period, if necessary, the full range of immunosuppressive treatment may be administered for cases unresponsive to corticosteroid treatments, such as tetracyclines, nicotinamide, cyclophosphamide, ciclosporin, goserelin, azathioprine, dapsone, rituximumab, or plasmaphoresis, or intravenous immunoglobulin may sometimes be considered when the symptoms are severe.[citation needed]

There is no cure for GP. Women who have GP are considered in remission if they are no longer blistering. Remission can last indefinitely, or until a subsequent pregnancy. GP usually occurs in subsequent pregnancies; however, it often seems more manageable because it is anticipated.[citation needed]

See also

- Bullous pemphigoid

- Cicatricial pemphigoid

- List of target antigens in pemphigoid

- List of immunofluorescence findings for autoimmune bullous conditions

References

- ^ Ambros-Rudolph CM, Müllegger RR, Vaughan-Jones SA, Kerl H, Black MM (March 2006). "The specific dermatoses of pregnancy revisited and reclassified: results of a retrospective two-center study on 505 pregnant patients". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 54 (3): 395–404. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.12.012. PMID 16488288.

- ^ Kroumpouzos G, Cohen LM (July 2001). "Dermatoses of pregnancy". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 45 (1): 1–19, quiz 19–22. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.114595. PMID 11423829.

- ^ Boulinguez S, Bédane C, Prost C, Bernard P, Labbé L, Bonnetblanc JM (2003). "Chronic pemphigoid gestationis: comparative clinical and immunopathological study of 10 patients". Dermatology. 206 (2): 113–9. doi:10.1159/000068467. PMID 12592077. S2CID 40685551.

- ^ Beard, M. P.; Millington, G. W. M (2012). "Recent developments in the specific dermatoses of pregnancy". Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 37 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04173.x. PMID 22007708. S2CID 5428325.

- ^ Chi, C-C.; Wang, S-H; Charles-Holmes, R.; Ambros-Rudolph, C.; Powell, J.; Jenkins, R.; Black, M.; Wojnarowska, F. (2012). "Pemphigoid gestationis: early onset and blister formation are associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes". British Journal of Dermatology. 160 (6): 1222–1228. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09086.x. PMID 19298272. S2CID 39630692.

- ^ Engineer, Leela; Bhol, Kailash; Ahmed, A.Razzaque (2000). "Pemphigoid gestationis: A review". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 183 (2): 483–491. doi:10.1067/mob.2000.105430. ISSN 0002-9378. PMID 10942491.

- ^ BP180NC16a ELISA May Be Useful in Serodiagnosis of Pemphigoid Gestationis. Medscape: June 21, 2005

- ^ Castro LA, Lundell RB, Krause PK, Gibson LE (November 2006). "Clinical experience in pemphigoid gestationis: report of 10 cases". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 55 (5): 823–8. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.07.015. PMID 17052488.