Hale White

William Hale White (22 December 1831 – 14 March 1913), known by his pseudonym Mark Rutherford, was a British writer and civil servant.[1] His obituary in The Times stated that the "employment of a pseudonym, and sometimes of two (for some of 'Mark Rutherford's' work was 'edited by his friend, Reuben Shapcott'), was sufficient to prove a retiring disposition, and Mr. Hale White was little before the world in person."[1]

Life, career and memorials

White was born in Bedford. His father, William White, a member of the Nonconformist community of the Bunyan Meeting, became well known as a doorkeeper at the House of Commons and wrote sketches of parliamentary life for the Illustrated Times.[2][3] A selection of his parliamentary sketches was published posthumously, in 1897, by Justin McCarthy, the Irish nationalist MP, as The Inner Life of the House of Commons.[4]

White himself was educated at Bedford Modern School[5] until the family moved to London.[6] There he was trained for the Congregational ministry, but the development of his views prevented his taking up that career; the same unconventional views got him expelled from New College, London,[7] and he eventually became a clerk at the Admiralty.[2][6] In 1861 he began writing newspaper articles to increase his income, having met and married Harriet Arthur and started a family.[7]

He had already served an apprenticeship to journalism before he made his name, or rather his pen name, "Mark Rutherford", famous with three novels, supposedly edited by one Reuben Shapcott: The Autobiography of Mark Rutherford (1881), Mark Rutherford's Deliverance (1885) and The Revolution in Tanner's Lane (1887).[8][2][9] George Orwell called Deliverance "one of the best novels in English."[10]

Under his own name White translated Spinoza's Ethics (1883). His later books include Miriam's Schooling, and Other Papers (1890), Catherine Furze (2 vols, 1893), Clara Hopgood (1896), Pages from a Journal, with Other Papers (1900), and John Bunyan (1905).[2][9]

Hale White died in Groombridge on 14 March 1913.[1]

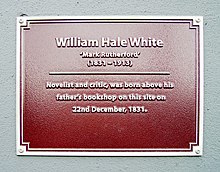

There is now a Mark Rutherford School in Bedford and a blue plaque commemorates White at 19 Park Hill in Carshalton.[11]

Family

White's first wife, Harriet, died in 1891 of multiple sclerosis. Two of their children had died in infancy.[7] In 1907, the widowed White met aspiring novelist Dorothy Smith, who was forty-five years his junior. They fell in love and were married three and a half years later, but enjoyed only two years of married life before his death.[12]

His eldest son by his first wife, Sir William Hale-White, was a distinguished doctor. His second son, Jack, married Agnes Hughes, one of Arthur Hughes' daughters. A third son became an engineer, and White's daughter Molly remained at home to care for her father.[7]

Selected publications

- The Autobiography of Mark Rutherford: Dissenting Minister Trubner and Co., London, 1881

- Mark Rutherford's Deliverance Trubner and Co., London, 1885

- The Revolution in Tanner's Lane Trubner and Co., London, 1887

- Miriam's Schooling Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co., London, 1890[13]

- Catharine Furze T. Fisher Unwin, London, 1893

- Clara Hopgood T. Fisher Unwin, London, 1896

Notes

- ^ a b c "'Mark Rutherford'". The Times. 17 March 1913. p. 42. Retrieved 19 April 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Rutherford, Mark". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 940.

- ^ Brake, Laurel; Demoor, Marysa (2009). Dictionary of Nineteenth-century Journalism in Great Britain and Ireland. ISBN 9789038213408. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ William White, The Inner Life of the House of Commons, edited with a preface by Justin McCarthy, MP, London, T. Fisher Unwin, 1897

- ^ Bedford Modern School of the black & red. OCLC 16558393.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Bedford Borough Council and Central Bedfordshire Council. "Mark Rutherford (William Hale White) - Digitised Resources - The Virtual Library". culturalservices.net. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d Michael Brealey (8 July 2014). Bedford's Victorian Pilgrim: William Hale White in Context. Authentic Publishers. pp. 20–. ISBN 978-1-78078-351-2.

- ^ Max Saunders, "Autobiografiction," Times Literary Supplement (3 October 2008), 13-15.

- ^ a b "Results for 'au:Rutherford, Mark,' [WorldCat.org]". worldcat.org. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ Orwell, George, "As I Please," December 3, 1943, Tribune.

- ^ "WHITE, WILLIAM HALE (1831–1913)". English Heritage. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ^ "Obituary of Dorothy Vernon Horace Smith, The Times". 28 August 1967. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ^ "Brief review of Miriam's Schooling, and other Papers". The Athenaeum (3274): 124. 26 July 1890.

References

- William James Dawson, "Religion in Fiction", a chapter, part of which is devoted to Hale White (on p. 283-289) in The Makers of English Fiction, 2nd ed., F.H. Revell Co., 1905.

- E. J. Feuchtwanger, White, William (1807–1882), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Cunningham, Valentine. "White, (William) Hale (1831–1913)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36864. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

External links

- Works by Hale White at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Mark Rutherford at Internet Archive

- Works by or about Hale White at Internet Archive

- Works by Hale White at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Mark Rutherford Resource