All's Well That Ends Well

All's Well That Ends Well is a play by William Shakespeare. Some academics believe it to have been written between 1604 and 1605.[1][2] It was published in the First Folio in 1623.

Though originally the play was classified as one of Shakespeare's comedies, the play is now considered by some critics to be one of his problem plays, so named because they cannot be neatly classified as tragedy or comedy. It is not among the playwright's most esteemed plays, with literary critic Harold Bloom writing that no one, "except George Bernard Shaw, ever has expressed much enthusiasm for All's Well That Ends Well."[3]

Characters

- King of France

- Duke of Florence

- Bertram, Count of Roussillon

- Countess of Roussillon, Mother of Bertram

- Lavatch, a Clown in her household

- Helena, a Gentlewoman protected by the Countess

- Lafew, an old Lord

- Parolles, a follower of Bertram

- An Old Widow of Florence, surnamed Capilet

- Diana, Daughter of the Widow

- Steward of the Countess of Roussillon

- Violenta (ghost character) and Mariana, Neighbours and Friends of the Widow

- A Page

- Soldiers, Servants, Gentlemen, and Courtiers

Capsule summary

Helena, the low-born ward of a French-Spanish countess, is in love with the countess's son Bertram, who is indifferent to her. Bertram goes to Paris to replace his late father as attendant to the ailing King of France. Helena, the daughter of a recently deceased doctor, follows Bertram, ostensibly to offer the King her services as a healer. The King is sceptical, and she guarantees the cure with her life: if he dies, she will be put to death, but if he lives, she may choose a husband from the court.

The King is cured and Helena chooses Bertram, who rejects her, owing to her poverty and low status. The King forces him to marry her, but after the ceremony Bertram immediately goes to war in Italy without so much as a goodbye kiss. He says that he will only marry her after she has borne his child and wears his family ring.

In Italy, Bertram is a successful warrior and also a successful seducer of local virgins. Helena follows him to Italy, befriends Diana, a virgin with whom Bertram is infatuated, and they arrange for Helena to take Diana's place in bed. Diana obtains Bertram's ring in exchange for one of Helena's. In this way Helena, without Bertram's knowledge, consummates their marriage and wears his ring.

Helena returns home to the countess, who is horrified at what her son has done, and claims Helena as her child in Bertram's place. Helena fakes her own death. Bertram, thinking he is free of her, comes home. He tries to marry a local lord's daughter, but Diana shows up and breaks up the engagement. Helena appears and explains the ring swap, announcing that she has fulfilled Bertram's challenge; Bertram, impressed by all she has done to win him, swears his love to her. Thus all ends well.

There is a subplot about Parolles – a disloyal associate of Bertram's. A recurring theme throughout the play is the similarity between love and war: conquering, seducing, betraying, outmaneuvering.

Synopsis

The play opens in Rousillon, then a Catalan province of Spain (now in France), where young Count Bertram bids farewell to his mother the Countess and Helena, as he leaves for the court of Paris (with old Lord Lafew) at the French King's order. Bertram's father has recently died and Bertram is to be the King's ward and attendant. Helena, a young minor noblewoman and ward of the Countess, whose father (a gifted doctor) has also recently died, laments her unrequitable love for (or infatuation with) Bertram, and losing him to Paris, which weighs on her though it seems to others that she mourns her father. Parolles, a cowardly military man and parasite on Bertram, trades wits with Helena, as they liken amorous love and the loss of virginity to military endeavours. Helena nearly admits her love of Bertram to Parolles before he leaves for Paris with Bertram and Lafew. Alone again, Helena convinces herself to strive for Bertram despite the odds, mentioning the King's illness alongside her decision.

In Paris, the King and noble lords discuss the Tuscan wars, where French nobles join on either side for their own glorification. Bertram, Parolles and Lafew arrive, and the King praises Bertram's father as more truly honorable, humble and egalitarian than the lords of his day or Bertram's. He welcomes Bertram as he would his own son.

In Rousillon, the Clown asks permission to marry which he and the Countess debate. The Steward explains to the Countess that he has overheard Helena lamenting her love for Bertram despite their social difference. The Countess, with sympathy and seeing Helena as her own daughter, coaxes a confession out of her. Helena admits her love, but (in decorum or strategy) reserves her previously realized ambition. They agree that Helena should travel to Paris to attempt to cure the King, even wagering her life for the opportunity.

In Paris, the King advises the Lords leaving for war, urging them to seek honor with amorous terms and warning them of the Italian women in warlike terms. Bertram, too young to go to war and in Paris to serve the King, is encouraged by Parolles and the Lords to steal away to the Tuscan war. He swears to the Lords that he will, but after they leave he admits (or reconsiders) to Parolles his intention to stay at the King's side.

Lafew asks the King to speak with Helena who offers to cure his fatal disease with her father's most potent and safeguarded recipe. The King acknowledges her late father's renown as a doctor, but refuses to entertain false hope. Through a series of arguments – showing her confidence, appealing to his irrational or mystical side, and underlining her father's reputation – she convinces the King to let heaven work through her. She accepts the King's warning that she will wager her life on the outcome, but to even the scales, she asks that she may choose her husband from the lords at court. The King agrees.

In Rousillon, the Countess sends the Clown to the Paris court with a letter for Helena, but not before the Clown teases the Countess with his impersonation of the courtiers as haughty and equivocating.

Back in Paris, Lafew tries to speak on the powers of heaven in a world of scientists, but Parolles interrupts him at every turn, trying to one-up him and claim Lafew's thoughts as his own. They bring the conversation to the King's miraculous recovery and the woman who cured him. The King and Helena enter, and the men are surprised to learn that the woman is Helena. (Lafew may be in disbelief, as he introduced Helena to the King for this purpose.) The King summons the lords and he and Helena make known their arrangement that she now choose a husband. Helena briefly questions a few of the lords, the first two of which may give perfunctory consent in front of the King, while haughtily equivocating like the Clown demonstrated previously. Helena chooses Bertram by way of giving herself to him, and the King seals her wish. Bertram balks, first asking the King to let his own eyes choose who he marries, then scorning her poverty and lack of (good) title.

The King counters Bertram's protests with offers money and title, and praises Helena variously to Bertram without his objection, but Bertram refuses again despite the King's practical beatitudes on virtue over status. The King, angered, threatens Bertram with ruin and his wrath. Bertram consents in word and the King will have them married without delay. Lafew mentions to Parolles' duty to Bertrand, and Bertram's recantation, which provoke a pique of haughty contempt from Parolles in which he disdains and threatens the old Lord. Lafew returns the animosity, and leaves and returns to announce Bertram married, and to further insult Parolles on his way through.

Bertram bemoans his fate to Parolles and plans his escape to the Tuscan wars, while sending Helena back home.

The Clown, having arrived, spars verbally with Parolles on the matter of his lack of title, duty and worth. Parolles delivers from Bertram his request that Helena take her leave of the King while Bertram attends “other business”.

Lafew tries in vain to convince Bertram of Parolles' empty viciousness. Bertram won't hear of it, and Lafew asks Bertram to mend relations between him and Parolles, likely sarcastically, since as soon as Parolles enters, Lafew subtly works toward a full indictment of Parolles as nothing but a shell of a man with a good suit on. Bertram tells Helena that he has urgent business to attend to as their surprise wedding has left him with unsettled matters, and that he will arrive at home in two days. She finds the courage to ask him for a farewell kiss, which he refuses.

In Florence, the local Duke and the French Lords discuss the King of France's abstention from the Tuscan war, and the Duke welcomes the participation of the many French lords who have come to seek honour and glory.

In Rousillon, the Clown informs the Countess of the marriage of Bertram and Helena, as well as Bertram's melancholy, adding that Clown has lost interest in the woman he wanted to marry after seeing the Parisian court's version of her. The Countess reads Bertram's letter, disapproving of his flight to Florence, and the Clown rattles off equivoques on cowardice in war and marriage.

Helena and the Lords returned from Florence enter to elaborate on Bertram's flight. Helena, dejected, reads Bertram's sardonic letter claiming that she'll have him as a husband once she gets his family ring and has his child. The Countess disavows him and claims Helena as her own daughter, giving the Lords this message of disapproval to take to Bertram. Helena, alone and hoping to give Bertram cause to return from the dangers of war, plans to disappear from Rousillon in the night.

In Florence, the Duke makes Bertram his cavalry officer.

In Rousillon, the Countess reads Helena's farewell letter, declaring her pilgrimage to Saint Jaques (putatively in Spain, or at least not in Florence or Rousillon). The Countess sends word of this to Bertram, hoping he'll return from Florence now that Helena is away.

In Florence, a Widow, her daughter Diana, Mariana and other women speak of the soldiers and watch or wait for them from afar. They discuss Bertram's success in war and his and Parolles' seduction of the local virgins. Helena arrives disguised as a pilgrim, who are hosted in Florence at the widow's house. She hears of Bertram's martial fame, his history, and his most recent attempts to seduce Diana, with more equivoques between war and the seduction of virgins. Helena befriends the women.

The Lords warn Bertram of Parolles' dishonorable behavior, staking their reputations with Bertram on its veracity. Bertram, now more receptive to the possibility, agrees with the Lords' scheme to send Parolles off to recover his drum, lost in the day's battle, so that on his return, they can capture him disguised as the enemy. Parolles enters to take the bait, and affecting pride, swears to recover it. Bertram takes a Lord to show him Diana.

Helena has identified herself to the Widow, a fallen estate noble, and enlisted her help for coin in order to get Bertram's family ring and switch Diana for Helena in a bed trick.

A French Lord and his soldiers lie in wait for Parolles, who bides his time and wonders how long of a story and how many self-inflicted injuries will satisfy the others when he doesn't return with a drum. The disguised French ambush him, and he immediately panics and offers information on the Florentine cause.

At the Widow's house, Bertram attempts to woo Diana who questions his motives and sincerity. Once Bertram attests that he is eternally sincere, and guileless, Diana plies him for the ring, offering to trade it for a ring (from Helena) and her virginity. Bertram accepts.

The Lords discuss Bertram's letter from his mother expressing her disapproval, how it negatively affects him, his caddish behavior, and the recently received rumor of Helena's death at Saint Jaques. Bertram enters, having arranged his affairs for departure no sooner than having heard of Helena's death. The Lords, hoping he see the error of his ways through Parolles' unmasking, take him to the blindfolded Parolles, who readily offers martial information on Florence to save himself with hardly a provocation, as before. He is equally forthwith in besmirching Bertram's character to the "enemy" on discovery of a note to Diana, advising her to leech money from Bertram as he tries to seduce her since he will betray her afterward (ostensibly written to her in an undelivered compact to bilk Bertram of gold). They reveal themselves and shame Parolles into near-silence. Alone and humbled, he concludes to follow them back to France.

Helena, the Widow and Diana discuss their success (the seduction having happened offstage between IV.ii. and IV.iii.) and Helena muses on the love-hate of Bertram, (or tricked-seducers of his kind, or men in general) during the sexual act. She asks the Widow and Diana to accompany her to the King in order to complete her winning or cornering of Bertram.

In Rousillon, the Countess, Lafew and the Clown mourn the loss of Helena. Lafew has proposed to the King that Bertram marry his daughter, which meets with the Countess' approval.

In Marseilles, Helena, the Widow and Diana send a Gentleman ahead of them to Rossillon with a letter to the King concerning Bertram.

In Rousillon, Parolles, now a reeking beggar, begs for help from Lafew, who allows him in for supper.

The King, Lafew and the Countess mourn the loss of Helena and decide to forgive Bertram's foolish young pride. Lafew and Bertram have arranged his marriage to Lafew's daughter, and the King consents. Bertram enters, asking forgiveness, and expanding on his love for Lafew's daughter, whom he loved at first sight. This love provoked his disdain for Helena, whom he belatedly appreciates.

Lafew, whose estate will pass to Bertram in the marriage, asks for a ring from Bertram to give to his daughter. Bertram gives him the ring from Diana (which came from Helena). The King, Lafew and the Countess recognize it as the ring that the King gave to Helena, which Bertram denies. The King has him seized, suspecting foul play (the King knows that she would only surrender it to Bertram in their bed, and Bertram believes that this is an impossibility). The Gentleman arrives, giving the letter from Diana and Helena to the King, in which it is claimed that Bertram pledged to marry Diana as soon as Helena has died. Lafew rescinds his daughter's hand.

Diana and the Widow enter and Bertram agrees he knows them, but not that he seduced her or promised her marriage, claiming she is a Florentine harlot. Diana shows Bertram's family ring, and claims Parolles as witness to Bertram's efforts to woo her. Bertram changes his story, claiming to have foolishly given her the ring as over-payment for her harlotry. Diana further claims Helena's ring, as recognized by the court, as the one she gave Bertram in bed. With the confusion reaching a peak, Parolles, once pressed, admits that Bertram seduced and bedded her, and Diana equivocates over how she got Helena's ring. The King order her arrest as well, and she then summons the Widow and Helena.

After the court's shock, Helena explains the rings, and that she has fulfilled the conditions of Bertram's sardonic challenge. Bertram swears to love her if she has honestly done all of this and can explain it. Helena pledges honesty, or righteous divorce for Bertram. Lafew accepts Parolles as a servant. The King offers Diana a dowry and her choice of husband.

The play ends as the actor playing the King steps forward in epilogue, declaring that all is well if Helena and Bertram speak truthfully, and asks for the audience's approval.

Sources

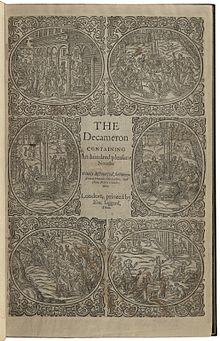

The play is based on a tale (3.9) of Boccaccio's The Decameron. Shakespeare may have read an English translation of the tale in William Painter's Palace of Pleasure.[4]

The name of the play expresses the proverb All's well that ends well, which means that problems do not matter so long as the outcome is good.[5]

Analysis and criticism

There is no evidence that All's Well was popular in Shakespeare's own lifetime and it has remained one of his lesser-known plays ever since, in part due to its unorthodox mixture of fairy tale logic, gender role reversals and cynical realism. Helena's love for the seemingly unlovable Bertram is difficult to explain on the page, but in performance it can be made acceptable by casting an actor of obvious physical attraction or by playing him as a naive and innocent figure not yet ready for love although, as both Helena and the audience can see, capable of emotional growth.[6] This latter interpretation also assists at the point in the final scene in which Bertram suddenly switches from hatred to love in just one line. This is considered a particular problem for actors trained to admire psychological realism. However, some alternative readings emphasise the "if" in his equivocal promise: "If she, my liege, can make me know this clearly, I'll love her dearly, ever, ever dearly." Here, there has been no change of heart at all.[7] Productions like the National Theatre's 2009 run, have Bertram make his promise seemingly normally, but then end the play hand-in-hand with Helena, staring out at the audience with a look of "aghast bewilderment" suggesting he only relented to save face in front of the King.[8] A 2018 interpretation from director Caroline Byrne at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, London, effects Bertram's reconciliation with Helena by having him make good his vow (Act 2 Scene 2) of only taking her as his wife when she bears his child; as well as Bertram's ring, Helena brings their infant child to their final confrontation before the king.[9]

Many critics consider that the truncated ending is a drawback, with Bertram's conversion so sudden. Various explanations have been given for this. There is (as always) possibly missing text. Some suggest that Bertram's conversion is meant to be sudden and magical in keeping with the 'clever wench performing tasks to win an unwilling higher born husband' theme of the play.[10] Some consider that Bertram is not meant to be contemptible, merely a callow youth learning valuable lessons about values.[11] Contemporary audiences would readily have recognised Bertram's enforced marriage as a metaphor for the new requirement (1606), directed at followers of the Catholic religion, to swear an Oath of Allegiance to Protestant King James, suggests academic Andrew Hadfield of the University of Sussex.[12]

Many directors have taken the view that when Shakespeare wrote a comedy, he did intend there to be a happy ending, and accordingly that is the way the concluding scene should be staged. Elijah Moshinsky in his acclaimed BBC version in 1981 had his Bertram (Ian Charleson) give Helena a tender kiss and speak wonderingly. Despite his outrageous actions, Bertram can come across as beguiling; the filming of the 1967 RSC performance with Ian Richardson as Bertram has been lost, but by various accounts (The New Cambridge Shakespeare, 2003 etc.) he managed to make Bertram sympathetic, even charming. Ian Charleson's Bertram was cold and egotistical but still attractive.

One character that has been admired is that of the old Countess of Rousillon, which Shaw thought "the most beautiful old woman's part ever written".[7] Modern productions are often promoted as vehicles for great mature actresses; examples in recent decades have starred Judi Dench and Peggy Ashcroft, who delivered a performance of "entranc[ing]...worldly wisdom and compassion" in Trevor Nunn's sympathetic, "Chekhovian" staging at Stratford in 1982.[7][13][14] In the BBC Television Shakespeare production she was played by Celia Johnson, dressed and posed as Rembrandt's portrait of Margaretha de Geer.

It has recently been argued that Thomas Middleton collaborated with Shakespeare on the play.[2]

Performance history

No records of the early performances of All's Well That Ends Well have been found. In 1741 the work was played at Goodman's Fields, with a later transfer to Drury Lane.[15] Rehearsals at Drury Lane started in October 1741 but William Milward (1702–1742), playing the king, was taken ill, and the opening was delayed until the following 22 January. Peg Woffington, playing Helena, fainted on the first night and her part was read. Milward was taken ill again on 2 February and died on 6 February.[16] This, together with unsubstantiated tales of more illnesses befalling other actresses during the run, gave the play an "unlucky" reputation, similar to that attached to Macbeth, and this may have curtailed the number of subsequent revivals.[15][17]

Henry Woodward (1714–1777) popularised the part of Parolles in the era of David Garrick.[18] Sporadic performances followed in the ensuing decades, with an operatic version at Covent Garden in 1832.[19]

The play, with plot elements drawn from romance and the ribald tale, depends on gender role conventions, both as expressed (Bertram) and challenged (Helena). With evolving conventions of gender roles, Victorian objections centred on the character of Helena, who was variously deemed predatory, immodest and both "really despicable" and a "doormat" by Ellen Terry, who also – and rather contradictorily – accused her of "hunt[ing] men down in the most undignified way".[20] Terry's friend George Bernard Shaw greatly admired Helena's character, comparing her with the New Woman figures such as Nora in Henrik Ibsen's A Doll's House.[7] The editor of the Arden Shakespeare volume summed up 19th century repugnance: "everyone who reads this play is at first shocked and perplexed by the revolting idea that underlies the plot."[21]

In 1896 Frederick S. Boas coined the term "problem play" to include the unpopular work, grouping it with Hamlet, Troilus and Cressida and Measure for Measure.[22]

References

- ^ Snyder, Susan (1993). "Introduction". The Oxford Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 20–24. ISBN 978-0-19-283604-5.

- ^ a b Maguire, Laurie; Smith, Emma (19 April 2012). "Many Hands – A New Shakespeare Collaboration?". The Times Literary Supplement. also at Centre for Early Modern Studies, University of Oxford accessed 22 April 2012: "The recent redating of All’s Well from 1602–03 to 1606–07 (or later) has gone some way to resolving some of the play’s stylistic anomalies" ... "[S]tylistically it is striking how many of the widely acknowledged textual and tonal problems of All’s Well can be understood differently when we postulate dual authorship."

- ^ Bloom, Harold, ed. (2010). All's Well that Ends Well. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 1604137088.

- ^ F. E. Halliday, A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964, Baltimore, Penguin, 1964; p. 29.

- ^ The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, 3rd ed., 2002. Cited at Bartleby.com Archived 1 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ McCandless, David (1997). "All's Well That Ends Well". Gender and performance in Shakespeare's problem comedies. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 57–59. ISBN 0-253-33306-7.

- ^ a b c d Dickson, Andrew (2008). "All's Well That Ends Well". The Rough Guide to Shakespeare. London: Penguin. pp. 3–11. ISBN 978-1-85828-443-9.

- ^ Billington, Michael (29 May 2009). "Theatre review: All's Well That Ends Well / Olivier, London". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- ^ Taylor, Paul (18 January 2018). "All's Well That Ends Well, review: Eye-opening and vividly alive". The Independent.

- ^ W. W. Lawrence, Shakespeare's Problem Comedies 1931.

- ^ J. G. Styan Shakespeare in Performance 1984; Francis G Schoff Claudio, Bertram and a Note on Inerpretation, 1959

- ^ Hadfield, Andrew (August 2017). "Bad Faith". Globe: 48–53. ISSN 2398-9483.

- ^ Kellaway, Kate (14 December 2003). "Judi...and the beast". The Observer. UK. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ^ Billington, Michael (2001). One Night Stands: a Critic's View of Modern British Theatre (2 ed.). London: Nick Hern Books. pp. 174–176. ISBN 1-85459-660-8.

- ^ a b Genest, John (1832). Some account of the English stage: from the Restoration in 1660 to 1830. Vol. 3. Bath, England: Carrington. pp. 645–647.

- ^ Highfill, Philip (1984). A biographical dictionary of actors, actresses, musicians, dancers, managers and other stage personnel in London, 1660–1800. Vol. 10. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-8093-1130-9.

- ^ Fraser (2003: 15)

- ^ Cave, Richard Allen (2004). "Woodward, Henry (1714–1777)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29944.

- ^ William Linley's song "Was this fair face" was written for All's Well That Ends Well.

- ^ Ellen Terry (1932) Four Essays on Shakespeare

- ^ W. Osborne Brigstocke, ed. All's Well That Ends Well, "Introduction" p. xv.

- ^ Neely, Carol Thomas (1983). "Power and Virginity in the Problem Comedies: All's Well That Ends Well". Broken nuptials in Shakespeare's plays. New Haven, CT: University of Yale Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-300-03341-0.

Bibliography

- Evans, G. Blakemore, The Riverside Shakespeare, 1974

- Fraser, Russell (2003). All's Well That Ends Well. The New Cambridge Shakespeare (2 ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53515-1.

- Lawrence, W. W., Shakespeare's Problem Comedies, 1931

- Price, Joseph G., The Unfortunate Comedy, 1968

- Schoff, Francis G., "Claudio, Bertram, and a Note on Interpretation", Shakespeare Quarterly, 1959

- Styan, J. G., Shakespeare in Performance series: All's Well That Ends Well, 1985

External links

- Folger Shakespeare Library: All's Well That Ends Well

- MaximumEdge.com Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well – searchable scene-indexed version of the play.

All's Well That Ends Well public domain audiobook at LibriVox

All's Well That Ends Well public domain audiobook at LibriVox