Anishinaabe

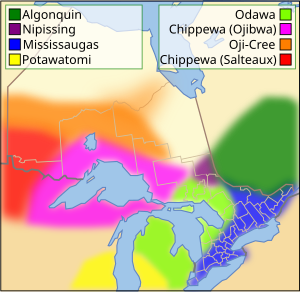

Homelands of Anishinaabe and Anishinini, ca. 1800 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Canada (Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba) United States (Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and Wisconsin) | |

| Languages | |

| English, French, Ojibwe (Including Odawa), Potawatomi, and Algonquin | |

| Religion | |

| Midewiwin, Catholicism, Methodism, and others | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Odawa, Ojibwe, Potawatomi, Oji-Cree, and Algonquin peoples |

Anishinaabe (or Anishinabe, plural: Anishinaabeg) is the autonym for a group of culturally related indigenous peoples of Canada and the United States that include the Odawa, Ojibwe, Potawatomi, Oji-Cree, Mississaugas, and Algonquin peoples. The Anishinaabeg speak Anishinaabemowin, or Anishinaabe languages that belong to the Algonquian language family. They traditionally have lived in the Northeast Woodlands and Subarctic.

The word Anishinaabeg translates to "people from whence lowered." Another definition refers to "the good humans," meaning those who are on the right road or path given to them by the Creator Gitche Manitou, or Great Spirit. The Ojibwe historian, linguist, and author Basil Johnston wrote that its literal translation is "Beings Made Out of Nothing" or "Spontaneous Beings," since Anishinaabeg myths claim they were created by divine breath.[1]

Anishinaabe is often mistakenly considered a synonym of Ojibwe; however, it refers to a much larger group of tribes.

Name

Anishinaabe has many different spellings. Different spelling systems may indicate vowel length or spell certain consonants differently (Anishinabe, Anicinape); meanwhile, variants ending in -eg/ek (Anishinaabeg, Anishinabek) come from an Algonquian plural, while those ending in an -e come from an Algonquian singular.

The name Anishinaabe is shortened to Nishnaabe, mostly by Odawa people. The cognate Neshnabé comes from the Potawatomi, a people long allied with the Odawa and Ojibwe in the Council of Three Fires. Identified as Anishinaabe, but not part of the Council of Three Fires, are the Nipissing, Mississaugas and Algonquin.

Closely related to the Ojibwe and speaking a language mutually intelligible with Anishinaabemowin (Anishinaabe language) are the Oji-Cree (also known as "Severn Ojibwe"). Their most common autonym is Anishinini (plural: Anishininiwag) and they call their language Anishininiimowin.

Among the Anishinaabeg, the Ojibwe collectively call the Nipissings and the Algonquins Odishkwaagamii (those who are at the end of the lake),[2] while those among the Nipissings who identify themselves as Algonquins call the Algonquins proper Omàmiwinini (those who are downstream).[3]

Not all Anishinaabemowin-speakers call themselves Anishinaabeg. The Ojibwe people who moved to what are now the prairie provinces of Canada call themselves Nakawē(-k) and call their branch of the Anishinaabe language Nakawēmowin. (The French ethnonym for the group was the Saulteaux). Particular Anishinaabeg groups have different names from region to region.

Origins

According to Anishinabe tradition, and from records of wiigwaasabak (birch bark scrolls), the people migrated from the eastern areas of North America, and from along the East Coast. In old stories, the homeland was called Turtle Island. This comes from the idea that the universe, the Earth, or the continent of North America are all sometimes understood as being the back of a great turtle, a mysterious natural consciousness. The Anishinaabe oral history considers the Anishinaabe peoples as descendents of the Abenaki people and refers to them as the "Fathers". Another Anishinaabe oral history considers the Abenaki as descendents of the Lenape (Delaware), thus refers to them as "Grandfathers". However, Cree oral traditions generally consider the Anishinaabe as their descendants, and not the Abenakis.

A number of complementary origin concepts exist within the oral traditions of the Anishinaabe. According to the oral history, seven great miigis (radiant/iridescent beings in human form) appeared to the Anishinaabe peoples in the Waabanakiing (Land of the Dawn, i.e., Eastern Land) to teach the people about the midewiwin life-style. One great miigis was too spiritually powerful and would kill people in the Waabanakiing whenever they were in its presence. This being later returned to the depths of the ocean, leaving the six great miigis to teach the people.

The Anishinaabe are one of the First Nations in Canada.

Clans

Each of the six miigis established separate doodem (clans) for the people. Of these doodem, five clan systems appeared:

- Awaazisii (Bullhead),

- Baswenaazhi (Echo-maker, i.e., Crane),

- Aan'aawenh (Pintail Duck),

- Nooke (Tender, i.e., Bear), and

- Moozoonii (Little Moose). Later a sixth was added.

- Waabizheshi (Marten).

After founding the doodem, the six miigis returned to the depths of the ocean as well. Some oral histories surmise that if the seventh miigis had stayed, it would have established the Animikii Thunderbird doodem.

The powerful miigis returned in a vision relating a prophecy to the people. It said that the Anishinaabeg needed to move west to keep their traditional ways alive, because of the many new settlements and people not of Anishinaabe blood who would soon arrive. The migration path of the Anishinaabe peoples would become a series of smaller Turtle Islands, confirmed by the miigis shells (i.e., cowry shells). After receiving assurance from their "Allied Brothers" (i.e., Mi'kmaq) and "Father" (i.e., Abnaki) of their safety in crossing other tribal territory, the Anishinaabeg moved inland. They advanced along the St. Lawrence River to the Ottawa River and through to Lake Nipissing, and then to the Great Lakes.

The first of these smaller Turtle Islands was Mooniyaa, where Mooniyaang now stands. Here the Anishinaabeg divided into two groups: one that travelled up and settled along the Ottawa River, and the core group who proceeded to the "second stopping place" near Niagara Falls.

By the time the Anishinaabeg established their "third stopping place" near the present city of Detroit, the Anishinaabeg had divided into six distinct nations: Algonquin, Nipissing, Missisauga, Ojibwa, Odawa and Potawatomi. While the Odawa established their long-held cultural centre on Manitoulin Island, the Ojibwe established their centre in the Sault Ste. Marie region of Ontario, Canada. With expansion of trade with the French and later the British, fostered by availability of European small arms, members of the Council of Three Fires expanded southward to the Ohio River, southwestward along the Illinois River, and westward along Lake Superior, Lake of the Woods and the northern Great Plains. In their western expansion, the Ojibwa again divided, forming the Saulteaux, the seventh major branch of the Anishinaabeg.

As the Anishinaabeg moved inland, through both alliances and conquest, they incorporated various other closely related Algonquian peoples into the Anishinaabe Nation. These included, but were not limited to, the Noquet (originally part of the Menomini Tribe) and Mandwe (originally part of the Fox). Other incorporated groups can generally be identified by the individual's Doodem (Clan). Migizi-doodem (Bald Eagle Clan) generally identifies those whose ancestors were from the area of the present-day United States and Ma'iingan-doodem (Wolf Clan) as Santee Sioux.[citation needed]

Other Anishinaabe doodem thought to have migrated out of the core Anishinaabeg groupings, such as the Nibiinaabe-doodem (Merman Clan), which is now the "Water-spirit Clan" of the Winnebago or Ho-Chunk. Anishinaabe peoples now reside throughout North America, in both the northern United States and southern Canada, chiefly around the Great Lakes and Lake Winnipeg.

After this migration and the immigration of European newcomers to North America, many Anishinaabe tribe chiefs were coerced into signing treaties—in a language they did not speak nor could read—with the governments of the Dominion of Canada and the United States. Treaty 3 (of the Numbered Treaties) in Canada was signed in 1873 between the Anishinaabe (Ojibwa) people west of the Great Lakes and the government of Canada.[4] Through other treaties and resulting relocations, some Anishinaabeg now reside in the states of Kansas, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and Montana in the United States, and the provinces of Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia in Canada.

Historical relations between the Anishinaabeg and other indigenous groups

Historically, the Anishinaabe peoples maintained close alliances with Cree groups, including the Atikamekw, Montagnais, Moose Cree, Swampy Cree and Plains Cree. Other close allies included the Noos (Abenaki), Miijimaag, Nii'inaa-naadawe (Wendat), Omanoominiig, Wiinibiigoog and Zhaawanoog. Other closely related Algonquin groups such as the Zhiishiigwan and Amikwaa were incorporated into the Anishinaabe peoplehood through alliances.

Due to competing interests, from time to time the Anishinaabeg had strained relations with the various Iroquois nations, Sauk, Fox and Dakota peoples.

Historical relations between the Anishinaabeg and European settlers

The first of the Anishinaabeg to encounter European settlers were those of the Three Fires Confederation, within the states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania in the territory of the present-day United States, and southern Ontario and Quebec of Canada. Although there were many peaceful interactions between the Anishinaabeg and the European settlers, there were also times of turmoil and war. Warfare cost many lives on both sides.

The Anishinaabe dealt with Europeans through the fur trade, intermarriage, and performance as allies. Europeans traded with the Anishinaabe for their furs in exchange for goods, and also hired the men as guides throughout the lands of North America. The Anishinaabeg women (as well as other Aboriginal groups) began to intermarry with fur traders and trappers. Some of their descendants would later create a Métis ethnic group. Explorers, trappers and other European workers married or had unions with other Anishinaabeg women, and their descendants tended to form a Métis culture.

French colonialists

The earliest Europeans to encounter native peoples in the Great Lakes area were the French voyageurs. These men were professional canoe-paddlers who transported furs and other merchandise over long distances in the lake and river system of northern America. Such explorers gave French names to many places in present-day Minnesota, Michigan and Wisconsin. The French were mainly trappers and traders rather than settlers. So in general they got along with the native peoples much better than the English did, who often were settlers and took the land from the native inhabitants of the country. Much more often French people intermarried with American native women.

British colonialists

The ethnic identities of the Ojibwa, Odawa, and Potawatomi did not develop until after the Anishinaabeg reached Michilimackinac on their journey westward from the Atlantic coast. Using the Midewiwin scrolls, Potawatomi elder Shup-Shewana dated the formation of the Council of Three Fires to 796 AD at Michilimackinac.

In this Council, the Ojibwa were addressed as the "Older Brother," the Odawa as the "Middle Brother," and the Potawatomi as the "Younger Brother." Consequently, when the three Anishinaabe nations are mentioned in this specific order: Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi, it implies the Council of Three Fires as well. Each tribe had different functions: the Ojibwa were the "keepers of the faith," the Odawa the "keepers of trade," and the Potawatomi are the "keepers/maintainers of/for the fire" (boodawaadam). This was the basis for their exonyms of Boodewaadamii (Ojibwe spelling) or Bodéwadmi (Potawatomi spelling).

The Ottawa (also Odawa, Odaawa, Outaouais, or Trader) are a Native American and First Nations people. Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa (or Anishinaabemowin in Eastern Ojibwe syllabics) is the third most commonly spoken Native language in Canada (after Cree and Inuktitut), and the fourth most spoken in North America (behind Navajo, Cree, and Inuktitut). Potawatomi is a Central Algonquian language. It is spoken around the Great Lakes in Michigan and Wisconsin, as well as in Kansas in the United States. In southern Ontario in Canada, it is spoken by fewer than 50 people.

Though the Three Fires had several meeting places, they preferred Michilimackinac due to its central location. The Council met for military and political purposes. The Council maintained relations with other nations, both fellow Anishinaabeg: the Ozaagii (Sac), Odagaamii (Meskwaki), Omanoominii (Menominee), and non-Anishinaabeg: Wiinibiigoo (Ho-Chunk), Naadawe (Iroquois Confederacy), Nii'inaa-Naadawe (Wyandot), Naadawensiw (Sioux), Wemitigoozhi (France), Zhaaganaashi (England) and the Gichi-mookomaan (the United States). After the Europeans came into the country, the French built Fort Michilimackinac in the 18th century. After the Seven Years' War, the victorious English took over the fort, also using it as a trading post.

Through the totem-system (a totem is any entity which watches over or assists a group of people, such as a family, clan or tribe)[5] and promotion of trade, the Council generally had a peaceful existence with its neighbours. However, occasional unresolved disputes erupted into wars. The Council notably fought against the Iroquois Confederacy and the Sioux. During the Seven Years' War, the Council fought with France and against England, as it had longstanding trade relationships with the French.[citation needed] Conventional war however was a European import, complete with its signature of high casualty, cruelty and focus on resource acquisition. Ceremonial warfare that was the predominant mode prior to European contact parallels older forms of European chivalry, where combatants met oftentimes one-on-one honor bouts. These matches did not always end in casualties and they had no component of political or material gain attached.

Later, the Anishinaabeg established a relationship with the British similar to that they had with the French. They formed the Three Fires Confederation in reaction to conflict with encroaching settlers and continuing tensions with the British Canadian government, as well as that of the new United States after it established independence at the end of the eighteenth century. The letters of Colonel Henry Boquet and Jeffery Amherst of the British army reveal a plan to eliminate Anishnaabe people through the intentional distribution of smallpox infected materials at Fort Pitt circa 1763. Peter Harstead's article 'Sickness and Disease on the Wisconsin frontier' (1959) chronicles similar efforts made by Americans (the fur company at Mackinac circa 1770). In the later case a cask of liquor was wrapped in an American flag. Instructions were given that this gift not be opened until the Anishnaabe people present had returned to their home communities. Opening the gift early at Fon Du Lac people began to get sick, and one who had seen the disease before in Montreal recognized it as smallpox.

United States

The Three Fires Confederacy had conflict with the new United States after the American Revolution, as settlers kept encroaching on their territory. The Council became the core member of the Western Lakes Confederacy (also known as "Great Lakes Confederacy"), made up of the Wyandot, Algonquin, Nipissing, Sac, Meskwaki and other peoples.

During the Northwest Indian War and the War of 1812, the Three Fires Confederacy fought against the United States. Many Anishinaabe refugees from the Revolutionary War, particularly Odawa and Potawatomi, migrated north to British-held areas.

Those who remained east of the Mississippi River were subjected to the 1830 Indian Removal policy of the United States; among the Anishinaabeg, the Potawatomi were most affected. The Odawa had been removed from the settlers' paths, so only a handful of communities experienced removal. For the Ojibwa, removal attempts culminated in the Sandy Lake Tragedy and several hundred deaths. The Potawatomi avoided removal only by escaping into Ojibwa-held areas and hiding from US officials.

William Whipple Warren (1825–1853), a United States man of mixed-Ojibwe and European descent, became an interpreter, assistant to a trader to the Ojibwe, and legislator of the Minnesota Territory. A gifted storyteller and historian, he collected native accounts and wrote the History of the Ojibway People, Based Upon Traditions and Oral Statements, first published by the Minnesota Historical Society in 1885, some 32 years after his early death from tuberculosis. Given his Anglo-American father, Lyman Marcus Warren, and American education, the Ojibwe of the time did not consider Warren as "one of them". However, they retained friendly relations with him and considered him as a "half brother" due to his extensive knowledge of the Ojibwe language and culture and the fact that he had Ojibwe ancestry through his mixed Ojibwe-French mother, Marie Cadotte.[6] His work covered much of the culture and history of the Ojibwe, gathered from stories of the nation.

Warren identified the Crane and Loon clans as the two Chief clans among his mother's Anishinaabe people. Crane Clan was responsible for external governmental relationships, and Loon Clan was responsible for internal governance relationships. Warren believed that the British and United States governments had deliberately destroyed the clan system, or the polity of governance, when they forced indigenous nations to adopt representative government and direct elections of chiefs. Further, he believed such destruction led to many wars among the Anishinaabe. He also cited the experiences of other Native Nations in the US (such as the Creek, Fox and others). His work in its entirety demonstrated the significance of the clan system.[6]

After the Sandy Lake Tragedy, the government changed its policy to relocating tribes onto reservations, often by consolidating groups of communities. Conflict continued through the 19th century, as Native Americans and the United States had different goals. After the Dakota War of 1862, many Anishinaabe communities in Minnesota were relocated and further consolidated.

.

Relations today between the Anishinaabeg and their neighbours

Other indigenous groups

There are many Anishinaabeg reserves and reservations; in some places the Anishinaabeg share some of their lands with others, such as the Cree, the Dakota, Delaware, and the Kickapoo, among others. The Anishnabeg who "merged" with the Kickapoo tribe may now identify as being Kickapoo in Kansas and Oklahoma. The Prairie Potawatomi were the Ojibwe, Odawa and Potawatomi of Illinois and Wisconsin who were relocated to Kansas during the 19th century.

Canada

The Anishinaabe of Manitoba, particularly those along the east side of Lake Winnipeg, have had longstanding historical conflicts with the Cree people.

In addition to other issues shared by First Nations recognized by the Canadian government and other aboriginal peoples in Canada, the Anishinaabe of Manitoba [1], Ontario and Quebec have opposed the Energy East pipeline of Enbridge [2]. The Chippewa of Thames First Nation legally challenged the right of Ottawa to hold a pipeline hearing without their consent.[7] The project is also opposed by Ottawa River Riverkeepers [3] and was the basis of a June 2015 declaration of reclaimed sovereignty over the Ottawa River valley by several Anishinaabe peoples. [4][5][6]

United States

The relationship between the various Anishinaabe communities and the United States government has been steadily improving since the passage of the Indian Reorganization Act. Several Anishinaabe communities still experience tensions with the state governments, county governments and with non-Native American individuals and their groups.

In contemporary times, the Anishinaabe have worked to renew the clan system as a model for self-governance. They have drawn from the work of Ojibwe educator Edward Benton-Banai, who emphasizes education based on one's own culture. They believe using the clan system will also be a basis of cultural and political revitalization of the people.[citation needed] Clan originally meant extended family. In this system originally clans were represented by a changing cast of spokespeople at yearly meetings. In more recent times, clans have come to align personality characteristics with the animals that represent them. This shifts the focus from extended family governance to groups of people who have a particular kind of strength to offer to the community. For example, the deer clan is sometimes understood as having direction of hospitality toward visitors, whereas the crane clan or eagle clan, depending on region, may be aligned with leadership qualities. Conversations surrounding how to change current systems of governance to better match how the people governed themselves over millennia is always occurring throughout anishnaabeaki.

Major issues facing the various Anishinaabe communities are:

- cultural and language preservation or revitalization;

- full and independent federal recognition: some Anishinaabe communities are recognized by county or state governments, or are recognized by the federal government only as part of another tribe;

- band government is not always looked on as legitimate by the communities it claims to represent. This is because the original band council system was imposed by the U.S. and Canadian federal government as a pseudo-representative conciliatory puppet system, that complimented the supposed protectorate of the reservation (which was originally conceived as a kind of gulag archipelago). In many cases despite its inherent drawbacks the people have successfully used the band council system at times to forward the well being of the community. At other times, the band council system has been used as an insider trading house where federal governments and corporate partners manipulate deals that have the appearance of legitimacy, when in fact they have only persuaded members of a momentarily non-representative band council.

- one major discrepancy between the band council system and older systems of governance is the imposed presence of a Chief. European colonists when encountering Sachems (whose sole authority was to negotiate land use between family groups so that over-hunting would not occur) erroneously believed they were encountering village or community headmen. This historical error has had devastating effects for the formulation of local governance as many of the people themselves have come to believe that older systems of governance were hierarchical when in fact they were purely horizontal in power distribution between individuals.

- treaty rights: traditional means of support (hunting, fishing and gathering), establishment of reservations or upholding of the reservation boundaries per treaties and their amendments;

- personal health: diabetes and asthma affect many Anishinaabe communities at a rate higher than the general population; and

- mistrust of the mainstream medicine: non-consensual sterilization practiced in the Indian Health Service or IHS in the US, among other shortcomings and abuses has compromised the relationship between Anishnaabeg and practitioners of mainstream medicine. Mainstream medicine is still used, but oftentimes with great reluctance and caution.

- relationship with law enforcement: since its inception, the reservation system has been accompanied by oftentimes severe police brutality and a systematized effort to use the prison system to silence and terrorize Anishnaabeg. Even in some cases where police may be hired by the band council, brutality persists.[citation needed] This is often due to the aforementioned nebulousness of band council relevance, and the band councils sometimes penchant for corruption. Anishnaabeg communities constantly face having to make legal and policy reforms to address problems of this nature.

- social disparity: many Anishinaabeg suffer poor education, high unemployment, substance abuse/addiction and domestic violence at rates higher than the general population. These are symptomatic social characteristics of reflected in nearly all communities that suffer long occupations by foreign armies.

Education

In June 1994, the Chiefs at the Anishinabek Grand Council gathering at Rocky Bay First Nation, directed that, the Education Directorate formally establish the Anishinabek Education Institute (AEI) in accordance with the post secondary education model that was submitted and ratified with provisions for satellite campuses and a community based delivery system. (Res. 94/13){{citation needed|date=April 2015}

See also

Notes

- ^ Basil Johnston,Ojibway Heritage (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 199), 15.

- ^ Baraga, Frederic. (1878). A Dictionary of the Otchipwe Language, explained in English. Montréal: Beauchemin & Valois.

- ^ Cuoq, Jean André. (1886). Lexique de la Langue Algonquine. Montréal: J. Chapleau & Fils.

- ^ Alexander Morris. (1880). The Treaties of Canada with the Indians, Belfords, Clarke & Co., Toronto.

- ^ Merriem-Webster Online, http://www.merriam-webster.com/

- ^ a b William W. Warren. (2009). History of the Ojibway People, new intro and ed. by Theresa Schenk, St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1885; reprint, pp. iii-xxi, accessed 22 Feb 2010

- ^ https://intercontinentalcry.org/enbridge-and-the-national-energy-board-push-to-open-line-9-ahead-of-legal-challenge-by-indigenous-community/

References

- Benton-Banai, Edward. (2004). Creation—From the Ojibwa. The Mishomis Book: The Voice of the Ojibway. University of Minnesota Press. Juvenile Nonfiction.

- Cappel, Constance. (2006). Odawa Language and Legends: Andrew J. Blackbird and Raymond Kiogima. Xlibris, ISBN 1-59926-920-1 (Foundation for Endangered Languages Award)

- Warren, William W. (2009). Schenck, Theresa (ed.). History of the Ojibway (Second ed.). St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87351-643-3. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

Further reading

- Wendy Djinn Geniusz, Our Knowledge is Not Primitive: Decolonizing Botanical Anishinaabe Teachings (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2009). ISBN 978-0-8156-3204-7

External links

- Anishinabek Nation: Union of Ontario Indians official website

- Algonquin Anishinabeg Nation Tribal Council official website

- Sault Tribe of Chippewa Indians official website

- ‘Living’ Cybercartographic Atlas of Indigenous Perspectives and Knowledge by the Geomatics and Cartographic Research Centre at Carleton University

- Ojibwe: Waasa-Inaabidaa, a six-part documentary series by PBS

- First Nations in Manitoba

- First Nations in Ontario

- First Nations in Quebec

- First Nations in Saskatchewan

- Great Lakes tribes

- Indigenous peoples of the Subarctic

- Native American tribes in Indiana

- Native American tribes in Kansas

- Native American tribes in Michigan

- Native American tribes in Minnesota

- Native American tribes in Montana

- Native American tribes in North Dakota

- Native American tribes in Oklahoma

- Native American tribes in Wisconsin

- Odawa

- Ojibwe

- Potawatomi