Argentinosaurus

| Argentinosaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

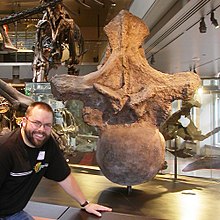

| Reconstructed skeleton, Museo Municipal Carmen Funes, Plaza Huincul, Argentina | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Clade: | †Macronaria |

| Clade: | †Titanosauria |

| Clade: | †Lognkosauria |

| Genus: | †Argentinosaurus Bonaparte & Coria, 1993 |

| Type species | |

| Argentinosaurus huinculensis | |

Argentinosaurus (meaning "Argentine lizard") is a genus of lognkosaurian titanosaur sauropod dinosaur first discovered by Guillermo Heredia in Argentina. The generic name refers to the country in which it was discovered. The dinosaur lived on the then-island continent of South America between 95.5 and 93.9 million years ago, during the Late Cretaceous Period. It is among the largest known dinosaurs.

Discovery

The only specimen was discovered thanks to the denunciation of Guillermo Heredia of the farm "Las Overas", about 8 km east of Plaza Huincul, in Neuquén Province, Argentina. At this point in time, staff of the Museo Carmen Funes in Plaza Huincul excavated a tibia (shinbone) on the farm, which was brought to the exhibition room of the museum. Later, in the summer of 1989, the remainder of the specimen was excavated by a team of the Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales, lead by the Argentine palaeontologist José F. Bonaparte. This additional material was likewise incorporated into the collection of the Museo Carmen Funes.[1] It included seven dorsal vertebrae (of the back region),[2] the underside of the sacrum including some sacral ribs, and a part of a dorsal rib (rib from the flank).[1]

Bonaparte presented the new find in 1989 at a scientific conference in San Juan. The formal description was published in 1993 by Bonaparte and Argentine paleontologist Rodolfo Coria, with the naming of a new genus and species, Argentinosaurus huinculensis. The generic name means "Argentine lizard", while the specific name refers to the town of Plaza Huincul.[1] The specimen, the holotype of A. huinculensis, is currently catalogued under the specimen number MCF-PVPH 1.[2] In 1996, Bonaparte referred a femur (upper thigh bone; specimen number MLP-DP 46-VIII-21-3) to the genus, which was put on exhibit at the Museo Carmen Funes. This bone was deformed front-to-back during fossilization. In 2004, Gerardo Mazzetta and colleagues mention a shaft of a femur (specimen number MLP-DP 46-VIII-21-3) as an additional referred bone. These authors further questioned the identification of the tibia, and argued that this bone is a left fibula instead.[3][4]

Description

Size

Argentinosaurus is among the largest known land animals, rivaled in size by other giant titanosaurs such as Puertasaurus, Alamosaurus, and Patagotitan.[5] The size of Argentinosaurus is difficult to estimate due to the incompleteness of its remains.[6] To counter this problem, paleontologists can compare the known material of Argentinosaurus to that of related sauropods known from more complete remains. The more complete taxon can then be scaled up to match the dimensions of Argentinosaurus. Mass can be estimated with equations based on the relationship between certain bone measurements and body mass, or through determining the volume of models.[7]

A reconstruction of Argentinosaurus created by Gregory S. Paul in 1994 yielded a length estimate of 30–35 metres (98–115 ft).[8] An length estimate of 30 metres (98 ft) by Coria was published later that year.[9] An unpublished estimate by Mortimer in 2001 used published reconstructions of Saltasaurus, Opisthocoelicaudia, and Rapetosaurus as guides and gave shorter length estimates of between 22–26 metres (72–85 ft).[10] In 2006, Carpenter reconstructed Argentinosaurus using the more complete Saltasaurus as a guide and arrived at a length of 30 metres (98 ft).[11] In 2008, Calvo and colleagues used the proportions of Futalognkosaurus to estimate the length of Argentinosaurus at less than 33 metres (108 ft).[12] Holtz gave a higher length estimate of 36.6 metres (120 ft) in 2012.[13] In 2013, Sellers and colleagues arrived at a length estimate of 39.7 metres (130 ft) and a shoulder height of 7.3 metres (24 ft) by measuring the skeletal mount in Museo Carmen Funes.[14] During the same year, Scott Hartman suggested that since Argentinosaurus was then thought to be a basal titanosaur, it would have a shorter tail and narrower chest than Puertasaurus, which he estimated to be about 27 metres (89 ft) long, indicating that it was slightly smaller.[15] In 2016, Paul estimated the length of Argentinosaurus at 30m.[16]

Paul estimated a body mass of 80–100 tonnes (88–110 short tons) for Argentinosaurus in 1994.[8] In 2004, Mazzetta and colleagues provided a range of 60–88 tonnes (66–97 short tons), and considered 73 tonnes (80 short tons) to be the most likely, making it the heaviest sauropod known from good material.[3] Thomas Holtz estimated a weight of 73–91 tonnes (80–100 short tons) in 2007.[17] In 2013, Sellers and Colleagues estimated a mass of 83.2 tonnes (91.7 short tons) by calculating the volume of the aforementioned Museo Carmen Funes skeleton.[14] In 2014, Benson and colleagues estimated the mass of Argentinosaurus at 90 tonnes (99 short tons).[18] In 2016, using equations that estimate body mass based on the circumference of the humerus and femur of quadrupedal animals, its weight was estimated at 96.4 tonnes (106.2 short tons).[19] Paul listed Argentinosaurus at 50 tonnes (55 short tons) or more in the same year.[20] In 2017, Carballido and colleagues estimated its mass at over 60 tonnes (66 short tons).[6]

Vertebrae

The vertebrae were enormous in size even for sauropod standards. One dorsal vertebra is reconstructed to an height of 159 centimeters and width of 129 centimeters. The vertebral centra (or "bodies") are up to 57 cm in width.[1] The dorsal vertebrae were opisthocoelous (concave at the rear), as in other macronarian sauropods.[1][4]: 205 As in many other titanosaurs, the vertebrae were cancellous (internally lightened by numerous small air-filled chambers). In both the dorsal and sacral vertebrae very large cavities around 4 to 6 centimeters in size were present.[21] The dorsal ribs were tubular and cylindrical in shape, in contrast to other titanosaurs.[1][22]: 309 Bonaparte and Coria, in their 1993 description, noted that the ribs were hollow, in contrast to many other sauropods. However, later authors argued that this hollowing could also have been due to erosion after death of the individual.[4] The sacral vertebrae, which were part of the hip region, had centra that were much reduced in size.[1]

Due to their incomplete preservation, the original position of the known dorsal vertebrae within the vertebral column is disputed. In their 1993 first description, Bonaparte and Coria interpreted two vertebrae as the first and second dorsal; another, reasonably complete vertebrae was suggested to be the third dorsal. The remaining three vertebrae, including two successive, articulated (still-connected) vertebrae, were considered to be part of the rear part of the dorsal column.[1] In a 2006 conference abstract, Novas and Ezcurra concurred with the interpretation of the third dorsal, but found that the first dorsal of Bonaparte and Coria was actually the fifth, and the second the tenth or eleventh. One of the isolated vertebrae of the rear portion was suggested to be the fourth, and the two articulated vertebrae to be the sixth and seventh.[23] Leonardo Salgado and Jaime Powell, in 2010, instead suggested the first dorsal of Bonaparte and Coria to probably be the third, the second to probably be the ninth, the third to be the probable fourth, the two articulated dorsals to be the sixth and seventh, and the other posterior dorsal to be the fifth. Another, undescribed vertebra was identified as a posterior dorsal by these authors.[2]

Another contentious issue is the presence or absence of the hyposphene-hypantrum articulations, accessory joints between vertebrae that stabilize the vertebral column. Difficulties in interpretation arise from the fragmentary preservation of the vertebral column; in addition, these joints are hidden from view in the two connected vertebrae.[21] Bonaparte and Coria, in 1993, suggested that the hyposphene-hypantrum atriculations were enlarged, similar to those of Epachthosaurus, and had additional articular surfaces below.[1] This was confirmed by some later authors, with Fernando Novas noting that the hypantrum (a bony extension below the prezygapophyses on the front face of a vertebra) extended sidewards and downwards, forming a much broadened surface that connects with the equally enlarged hyposphene at the back face of the following vertebra.[21][22]: 309–310 Other authors, however, argued that most titanosaur genera lacked hyposphene-hypantrum articulations altogether, and that the articular structures seen in Epachthosaurus and Argentinosaurus are instead thickened vertebral laminae (ridges).[21][24][25]: 55

Limbs

The referred shaft of the femur has a circumference of about 1.18 meters at its narrowest part. Reconstructed to its original length, it is around 2.5 meters long.[3] By comparison, the complete femora preserved in the other giant titanosaurs Antarctosaurus giganteus and Patagotitan mayorum measure 2.35 metres (7.7 ft) and 2.38 metres (7.8 ft), respectively.[3][6] The tibia, 155 cm in length, was slender and had a short cnemial crest, a prominent extension at the front of the upper end of the bone that anchored muscles that stretched the leg[1] The rear surface of the upper end of the tibia rises to a peak when seen in medial view, which is possibly a diagnostic feature.[22]: 309

Classification

Traditionally, the majority of sauropod fossils from the Cretaceous had been referred to a single family, the Titanosauridae, which was in use since 1893.[26] In their 1993 first description of Argentinosaurus, Bonaparte and Coria noted that the latter differed from typical titanosaurids in the presence of hyposphene-hypantrum articulations. As these articulations were likewise present in the titanosaurids Andesaurus and Epachthosaurus, Bonaparte and Coria proposed a separate family for the three genera, the Andesauridae. Both families were united into a new, higher group, the Titanosauria.[1] In 1997, Salgado and colleagues found Argentinosaurus to belong to Titanosauridae, in an unnamed clade with Opisthocoelicaudia and an indeterminate titanosaur.[27] In 2002, Argentinosaurus was recovered as a member of Titanosauria by Pisani and colleagues, and again found to be in a clade with Opisthocoelicaudia and an unnamed taxon, in addition to Lirainosaurus.[28] A 2003 study by Wilson and Upchurch found both Titanosauridae and Andesauridae to be invalid: the Titanosauridae because it was based on an non-diagnostic genus, Titanosaurus, and the Andesauridae because it was defined on plesiomorphic (primitive) features only.[26] A 2011 study by Mannion and Calvo found Andesauridae to be paraphyletic and likewise recommended its disuse.[29]

In 2004, Upchurch and colleagues introduced a new group, Lithostrotia, which included all more derived members of Titanosauria. Argentinosaurus was classified outside of this group, and thus as a more basal titanosaurian.[22]: 278 The basal position within Titanosauria was confirmed by a number of subsequent studies.[30][21][31][32][33] A 2017 study by Carballido and colleagues recovered it as a member of Lognkosauria and the sister taxon of Patagotitan.[6] In 2018, González Riga and colleagues also found it to belong in Lognkosauria, which in turn was found to belong to Lithostrotia.[34] Another 2018 study by Sallam and colleagues found two diffent phylogenetic positions for Argentinosaurus based on two different data sets. They considered it to be either a basal titanosaur or the sister taxon of Epachthosaurus.[35] In 2019, a study by González Riga and colleagues found Argentinosaurus to belong to Lognkosauria once again, and found this group to form a larger clade with Rinconsauria, which they named Colossosauria.[36]

The following cladogram shows the position of Argentinosaurus in Colossosauria according to González Riga and colleagues, 2019.[36]

Paleobiology

Biomechanics and speed

In 2013, in a study published in PLoS ONE on October 30, 2013 by Dr. Bill Sellers, Dr. Rodolfo Coria, Lee Margetts and colleagues, Argentinosaurus was digitally reconstructed to test its locomotion for the first time. Before computer simulations, the most common way of estimating speed was through studying bone histology and ichnology. Commonly, studies about sauropod bone histology and speed focus on the postcranial skeleton which holds many unique features, such as an enlarged process on the ulna, a wide lobe on the ilia, an inward-slanting top third of the femur, and an extremely ovoid femur shaft. Those features are useful when attempting to explain trackway patterns of graviportal animals. When studying ichnology to calculate sauropod speed, there are a few problems, such as only providing estimates for certain gaits because of preservation bias, and being subject to many more accuracy problems.[14]

To estimate the gait and speed of Argentinosaurus, the study performed a musculoskeletal analysis combined with computer simulations. Similar analyses have previously been conducted on hominids, terror birds, and other dinosaurs. To conduct the analysis, the team had to create a digital skeleton of the animal in question, estimate the muscles and their properties, and estimate the weight and how it's distributed. Then using computer simulation and genetic algorithms, which could be optimised for metabolic energy cost or speed, the digital Argentinosaurus learns to walk. The study estimated that their 83 tonne sauropod model was mechanically competent at a top speed of 2 m/s (5 mph) but was approaching a functional limit. The study concluded that much larger terrestrial vertebrates might be possible, but would require significant body remodeling and possibly behavioral change to prevent joint collapse.[14][37] The authors of the study noted that there are areas of the model that can be improved with future research, such as, gathering more data from living animals to improve the soft tissue reconstruction, using more complete sauropod specimens to confirm the studies findings, and performing sensitivity analysis.[14]

Paleoecology

Argentinosaurus was discovered in the Argentine Province of Neuquén. It was originally reported from the Huincul Group of the Río Limay Formation.[1] More recently, the units have been referred to as the Huincul Formation and the Río Limay Subgroup, the latter of which is a subdivision of the Neuquén Group. The Huincul Formation is composed of yellowish and greenish sandstones of fine to medium grain, some of which are tuffaceous. These deposits likely come from the Late Cenomanian age.[38]

Fossilized pollen indicates a wide variety of plants from the Huincul Formation. A study of the El Zampal section of the formation found hornworts, liverworts, ferns, Selaginellales, possible Noeggerathiales, gymnosperms (including gnetophytes and conifers), and angiosperms (flowering plants), in addition to several grains of unknown affinities.[39] The fauna of the Huincul Formation includes fish (including dipnoans), turtles, and crocodilians.[40]

In addition to Argentinosaurus, the Huincul Formation has yielded several other dinosaurs. These include other sauropods like the rebbachisaurids Cathartesaura[41] and Limaysaurus[42][43] and the titanosaur Choconsaurus.[44] Theropods, including carcharodontosaurids such as Mapusaurus[45] and Taurovenator, abelisauroids such as Skorpiovenator[46] and Ilokelesia, unenlagiines, and other theropods such as Aoniraptor and Gualicho[47] have also been discovered there.[40] Several iguanodonts have also been found in the Huincul Formation, including Gasparinisaura and some others that have not been identified.[48][38]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Bonaparte J, Coria R (1993). "Un nuevo y gigantesco sauropodo titanosaurio de la Formacion Rio Limay (Albiano-Cenomaniano) de la Provincia del Neuquen, Argentina". Ameghiniana (in Spanish). 30 (3): 271–282.

- ^ a b c Salgado, Leonardo; Powell, Jaime E. (2010). "Reassessment of the vertebral laminae in some South American titanosaurian sauropods". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (6): 1760–1772. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.520783. hdl:11336/73562.

- ^ a b c d Mazzetta, Gerardo V.; Christiansen, Per; Fariña, Richard A. (2004). "Giants and Bizarres: Body Size of Some Southern South American Cretaceous Dinosaurs" (PDF). Historical Biology. 16 (2–4): 71–83. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.694.1650. doi:10.1080/08912960410001715132. Retrieved January 8, 2008.

- ^ a b c Salgado, L.; Bonaparte, J. F. (2007). "Sauropodomorpha". Patagonian Mesozoic Reptiles. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 188–228. ISBN 978-0-253-34857-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Fowler, Denver W.; Sullivan, Robert M. (2011). "The first giant titanosaurian sauropod from the Upper Cretaceous of North America" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 56 (4): 685–690. doi:10.4202/app.2010.0105.

- ^ a b c d Carballido, José L.; et al. (2017). "A new giant titanosaur sheds light on body mass evolution among sauropod dinosaurs". Proc. R. Soc. B. 284 (1860): 20171219. doi:10.1098/rspb.2017.1219. PMC 5563814. PMID 28794222.

- ^ Paul, Gregory S. (1997). "Dinosaur models: the good, the bad, and using them to estimate the mass of dinosaurs" (PDF). In Wolberg, D. L.; Stump, E.; Rosenberg, G. D. (eds.). DinoFest International Proceedings. The Academy of Natural Sciences. pp. 129–154. Retrieved November 17, 2019.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Paul, Gregory S. (Autumn 1994). "Big Sauropods - Really, Really Big Sauropods" (PDF). The Dinosaur Report: 12–13. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ^ Appenzeller, Tim (1994). "Argentine dinos vie for heavyweight titles" (PDF). Science. 266 (5192): 1805. Bibcode:1994Sci...266.1805A. doi:10.1126/science.266.5192.1805. PMID 17737065.

- ^ Mortimer, Mickey (September 12, 2001). "Titanosaurs too Large?". Dinosaur Mailing List. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- ^ Carpenter, Kenneth (2006). "Biggest of the Big: A Critical Re-Evaluation of the Mega-Sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus Cope, 1878" (PDF). In Foster, John R.; Lucas, Spencer G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. Vol. 36. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. pp. 131–138.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Calvo, Jorge O.; Juárez Valieri, Rubén D.; Porfiri, Juan D. (2008). "Re-sizing giants: estimation of body lenght [sic] of Futalognkosaurus dukei and implications for giant titanosaurian sauropods". Congreso Latinoamericano de Paleontología de Vertebrados. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

- ^ Holtz, Thomas (2012). "Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e Sellers, W. I.; Margetts, L.; Coria, R. A. B.; Manning, P. L. (2013). Carrier, David (ed.). "March of the Titans: The Locomotor Capabilities of Sauropod Dinosaurs". PLoS ONE. 8 (10): e78733. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...878733S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078733. PMC 3864407. PMID 24348896.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Hartman, Scott (2013). "The biggest of the big". Skeletal Drawing. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- ^ S., Paul, Gregory (October 25, 2016). The Princeton field guide to dinosaurs (2nd ed.). Princeton, N.J. ISBN 9781400883141. OCLC 954055249.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Holtz, Thomas R. (2007). Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages. Random House. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-375-82419-7.

- ^ Benson, R. B. J.; Campione, N.S.E.; Carrano, M.T.; Mannion, P. D.; Sullivan, C.; Upchurch, P.; Evans, D. C. (2014). "Rates of Dinosaur Body Mass Evolution Indicate 170 Million Years of Sustained Ecological Innovation on the Avian Stem Lineage". PLoS Biology. 12 (5): e1001853. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001853. PMC 4011683. PMID 24802911.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ González Riga, Bernardo J.; Lamanna, Matthew C.; Ortiz David, Leonardo D.; Calvo, Jorge O.; Coria, Juan P. (2016). "A gigantic new dinosaur from Argentina and the evolution of the sauropod hind foot". Scientific Reports. 6: 19165. Bibcode:2016NatSR...619165G. doi:10.1038/srep19165. PMC 4725985. PMID 26777391.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Paul2016was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e Novas, Fernando E. (2009). The age of dinosaurs in South America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 204–205. ISBN 978-0-253-35289-7.

- ^ a b c d Upchurch, Paul; Paul M. Barret; Peter Dodson (2004). "Sauropoda". The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 259–322. ISBN 978-0-520-25408-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Novas, F. E.; Ezcurra, M. (2006). "Reinterpretation of the dorsal vertebrae of Argentinosaurus huinculensis (Sauropoda, Titanosauridae)". Ameghiniana. 43 (4): 48–49R.

- ^ Sanz, J.L.; Powell, J.E.; Le Loeuff, J.; Martínez, R.; Pereda Suberbiola, X. (1999). "Sauropod remains from the Upper Cretaceous of Laño (northcentral Spain). Titanosaur phylogenetic relationships". Estudios del Museo de Ciencias Naturales de Alava. 14 (1): 235–255.

- ^ Powell, Jaime Eduardo (2003). Revision of South American titanosaurid dinosaurs: palaeobiological, palaeobiogeographical and phylogenetic aspects. Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery.

- ^ a b Wilson, Jeffrey A.; Upchruch, Paul (2003). "A revision of Titanosaurus Lydekker (Dinosauria ‐ Sauropoda), the first dinosaur genus with a 'Gondwanan' distribution" (PDF). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 1 (3): 125–160. doi:10.1017/S1477201903001044.

- ^ Salgado, Leonardo; Coria, Rodalpho Anibal; Calvo, Jorge Orlando (1997). "Evolution of titanosaurid sauropods I.: Phylogenetic analysis based on the postcranial evidence". Ameghiniana. 34 (1): 3–32.

- ^ Pisani, Davide; Yates, Adam M.; Langer, Max C.; Benson, Michael J. (2002). "A genus-level supertree of the Dinosauria". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 269 (1494): 915–921. doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1942. PMC 1690971. PMID 12028774.

- ^ Mannion, Philip D.; Calvo, Jorge O. (2011). "Anatomy of the basal titanosaur (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) Andesaurus delgadoi from the mid-Cretaceous (Albian–early Cenomanian) Río Limay Formation, Neuquén Province, Argentina: implications for titanosaur systematics". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 163 (1): 155–181. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2011.00699.x.

- ^ Wilson, Jeffrey A. (2006). "An Overview of Titanosaur Evolution and Phylogeny". Actas de las III Jornadas Sobre Dinosaurios y Su Entorno. Burgos: Salas de los Infantes. 169: 169–190.

- ^ Filippi, Leonardo S.; García, Rodolfo A.; Garrido, Alberto C. (2011). "A new titanosaur sauropod dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous ofNorth Patagonia, Argentina" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 56 (3): 505–520. doi:10.4202/app.2010.0019.

- ^ Lacovara, Kenneth J.; Ibiricu, L.M.; Lamanna, M.C.; Poole, J.C.; Schroeter, E.R.; Ullmann, P.V.; Voegele, K.K.; Boles, Z.M.; Egerton, V.M.; Harris, J.D.; Martínez, R.D.; Novas, F.E. (September 4, 2014). "A Gigantic, Exceptionally Complete Titanosaurian Sauropod Dinosaur from Southern Patagonia, Argentina". Scientific Reports. 4: 6196. Bibcode:2014NatSR...4E6196L. doi:10.1038/srep06196. PMC 5385829. PMID 25186586.

- ^ González Riga, Bernardo J.; Lamanna, Matthew C.; Ortiz David, Leonardo D.; Calvo, Jorge O.; Coria, Juan P. (2016). "A gigantic new dinosaur from Argentina and the evolution of the sauropod hind foot". Scientific Reports. 6: 19165. Bibcode:2016NatSR...619165G. doi:10.1038/srep19165. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4725985. PMID 26777391.

- ^ Gonzalez Riga, B.J.; Mannion, P.D.; Poropat, S.F.; Ortiz David, L.; Coria, J.P. (2018). "Osteology of the Late Cretaceous Argentinean sauropod dinosaur Mendozasaurus neguyelap: implications for basal titanosaur relationships" (PDF). Journal of the Linnean Society. 184 (1): 136–181. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlx103. hdl:10044/1/53967.

- ^ Sallam, Hesham M.; Gorscak, Eric; O'Connor, Patrick M.; El-Dawoudi, Iman M.; El-Sayed, Sanaa; Saber, Sara; Kora, Mahmoud A.; Sertich, Joseph J. W.; Seiffer, Erik R.; Lamanna, Matthew C. (2018). "New Egyptian sauropod reveals Late Cretaceous dinosaur dispersal between Europe and Africa" (PDF). Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2 (3): 445–451. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0455-5. PMID 29379183.

- ^ a b González Riga, Bernardo J.; Lamanna, Matthew C.; Otero, Alejandro; Ortiz David, Leonardo D.; Kellner, Alexander W. A.; Ibiricu, Lucio M. (2019). "An overview of the appendicular skeletal anatomy of South American titanosaurian sauropods, with definition of a newly recognized clade". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 91 (suppl 2): e20180374. doi:10.1590/0001-3765201920180374. PMID 31340217.

- ^ "Argentinosaurus"

- ^ a b Leanza, Héctor A.; et al. (2004). "Cretaceous terrestrial beds from the Neuquén Basin (Argentina) and their tetrapod assemblages". Cretaceous Research. 25 (1): 61–87. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2003.10.005.

- ^ Vallati, Patricia (2001). "Middle cretaceous microflora from the Huincul Formation ("Dinosaurian Beds") in the Neuquén Basin, Patagonia, Argentina". Palynology. 25 (1): 179–197. doi:10.2113/0250179.

- ^ a b Motta, Matías J.; et al. (2016). "New theropod fauna from the Upper Cretaceous (Huincul Formation) of northwestern Patagonia, Argentina". Cretaceous Period: Biotic Diversity and Biogeography. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Bulletin. 71: 231–253.

- ^ de Jesus Faria, Caio César; et al. (2015). "Cretaceous sauropod diversity and taxonomic succession in South America". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 61: 154–163. Bibcode:2015JSAES..61..154D. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2014.11.008. hdl:11336/37899.

- ^ Calvo, Jorge O.; Salgado, Leonardo (1995). "Rebbachisaurus tessonei sp. nov. a new Sauropoda from the Albian-Cenomanian of Argentina; new evidence on the origin of the Diplodocidae". Gaia. 11: 13–33.

- ^ Salgado, Leonardo; Garrido, Alberto; Cocca, Sergio E.; Cocca, Juan R. (2004). "Lower Cretaceous rebbachisaurid sauropods from Cerro Aguada del León (Lohan Cura Formation), Neuquén Province, northwestern Patagonia, Argentina". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (4): 903–912. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2004)024[0903:lcrsfc]2.0.co;2.

- ^ SimóN, Edith; Salgado, Leonardo; Calvo, Jorge O. (2017). "A new titanosaur sauropod from the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia, Neuquén Province, Argentina". Ameghiniana. 55 (1): 1–29. doi:10.5710/AMGH.01.08.2017.3051.

- ^ Coria, Rodolfo A.; Currie, Philip J. (2006). "A new carcharodontosaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentina". Geodiversitas. 28 (1): 71–11.

- ^ Canale, Juan I.; et al. (2009). "New carnivorous dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of NW Patagonia and the evolution of abelisaurid theropods". Naturwissenschaften. 96 (3): 409–14. Bibcode:2009NW.....96..409C. doi:10.1007/s00114-008-0487-4. hdl:11336/52024. PMID 19057888.

- ^ Apesteguía, S; Smith, ND; Juárez Valieri, R; Makovicky, PJ (2016). "An Unusual New Theropod with a Didactyl Manus from the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina". PLoS ONE. 11 (7): e0157793. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1157793A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157793. PMC 4943716. PMID 27410683.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Coria, Rodolfo A.; Calvo, Jorge O. (2002). "A new iguanodontian ornithopod from Neuquén Basin, Patagonia, Argentina". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (3): 503–509. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0503:ANIOFN]2.0.CO;2.