Avon (county)

| Avon | |

|---|---|

Avon shown within England | |

| Area | |

| • 1974 | 332,596 acres (1,345.97 km2)[1] |

| • 1994 | 134,268 hectares (1,342.68 km2)[2] |

| Population | |

| • 1973 | 914,180[3] |

| • 1981 | 900,416 |

| • 1991 | 903,870 |

| History | |

| • Origin | Bristol travel-to-work area |

| • Created | 1974 |

| • Abolished | 1996 |

| • Succeeded by | Bristol South Gloucestershire North Somerset Bath and North East Somerset |

| Status | Non-metropolitan county |

| ONS code | 08 |

| Government | Avon County Council |

| • HQ | Bristol |

Coat of arms of Avon County Council | |

| Subdivisions | |

| • Type | Non-metropolitan districts |

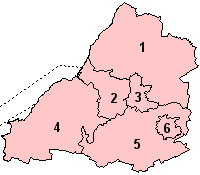

| • Units | 1. Northavon 2. Bristol 3. Kingswood 4. Woodspring 5. Wansdyke 6. Bath |

| |

Avon /ˈeɪvən/ was, from 1974 to 1996, a non-metropolitan and ceremonial county in the west of England.

The county was named after the River Avon, which runs through the area. It was formed from parts of the historic counties of Gloucestershire and Somerset, together with the City of Bristol. In 1996, the county was abolished and the area split between four new unitary authorities: Bath and North East Somerset, Bristol, North Somerset and South Gloucestershire. The Avon name is still used for some purposes. The area had a population of approximately 1.08 million people in 2009.[4]

Background

The port of Bristol lies close to the mouth of the River Avon which formed the historic boundary between Gloucestershire and Somerset. In 1373 a charter constituted the area as the County of the Town of Bristol, although it continued to fall within the jurisdiction of the two counties for some purposes.[5]

The appointment of a boundaries commission in 1887 led to a campaign for the creation of a county of Greater Bristol. The commissioners, while recommending that Bristol should be "neither in the county of Gloucester nor of Somerset for any purpose whatsoever", did not extend the city's boundaries.[6] The commission's timidity was attacked by the Bristol Mercury and Daily Post, who accused them of using the "crude method of the Procrustean bed".[7] The newspaper went on to attack Charles Ritchie, the President of the Local Government Board, and the Conservative government:

Everyone who considered the question on its merits was convinced of the justice of the demand for a Greater Bristol, but... the interests of the Tory party were put before every other consideration and we do not think there is any endeavour to conceal the fact.[8]

Under the Local Government Act 1888 Bristol was constituted a county borough, exercising the powers of both a county and city council. The city was extended to take in some Gloucestershire suburbs in 1898 and 1904.[9]

The Local Government Boundary Commission appointed in 1945 recommended the creation of a "one-tier county" of Bristol based on the existing county borough, but the report was not acted upon.[10]

The next proposals for local government reform in the area were made in 1968, when the Redcliffe-Maud Commission made its report. The commission recommended dividing England into unitary areas. One of these was a new Bristol and Bath Area which would have included a wide swathe of countryside surrounding the two cities, extending into Wiltshire and as far as Frome in Somerset.[11] Following a change of government at the 1970 general election, a two-tier system of counties and districts was proposed instead of unitary authorities. In a white paper published in 1971 one of these counties "Area 26" or "Bristol County", was based on the commission's Bristol and Bath area, but lacked the areas of Wiltshire.[12] The proposals were opposed by Somerset County Council, and this led to the setting up of a "Save Our Somerset" campaign.[13]

By the time the Local Government Bill was introduced to Parliament, the county had been named "Avon".[14] The boundaries of the new county were cut back during the passage of Local Government Bill through Parliament.[15] The Local Government Act 1972 received the Royal Assent on 26 October 1972.

Creation

The county came into formal existence on 1 April 1974 when the Local Government Act 1972 came into effect. The new county consisted of the areas of:

- The county boroughs of Bristol and Bath,

- Part of the Administrative County of Gloucestershire:

- Kingswood Urban District, Mangotsfield Urban District

- Warmley Rural District, most of Sodbury Rural District and most of Thornbury Rural District

- Part of the Administrative County of Somerset:

- Municipal Borough of Weston-super-Mare

- Clevedon Urban District, Keynsham Urban District, Norton-Radstock Urban District, Portishead Urban District,

- Bathavon Rural District, Long Ashton Rural District, part of Axbridge Rural District and part of Clutton Rural District.

The county was divided into six districts:

- Bristol and Bath had identical boundaries to the former county boroughs.

- In the north, two districts were created:

- the urban districts of Kingswood and Mangotsfield, and the rural district of Warmley formed a single District of Kingswood,

- the rest of the areas transferred from Gloucestershire (the rural districts of mostly Sodbury and mostly Thornbury) became the District of Northavon.

- In the south, there were two districts:

- on the coast: Woodspring (merger of the municipal borough of Weston-super-Mare, the urban districts of Clevedon and Portishead, and the rural districts of Long Ashton and part of Axbridge),

- and in the interior: Wansdyke (merger of the urban districts of Keynsham and Norton-Radstock, and the rural districts of Bathavon and part of Clutton).

To the north the county bordered Gloucestershire, to the east Wiltshire and to the south Somerset. In the west it had a coast on the Severn Estuary and Bristol Channel.

The area of Avon was 520 square miles (1,347 km2) and its population in 1991 was 919,800. Cities and towns in Avon included (in approximate order of population) Bristol, Bath, Weston-super-Mare, Yate, Clevedon, Portishead, Midsomer Norton & Radstock, Bradley Stoke, Nailsea, Yatton, Keynsham, Kingswood, Thornbury, Filton and Patchway.

Demise

Avon was one of the counties in the "first tranche" of reviews conducted by the Banham Commission in the 1990s. The Commission recommended that it and its districts be abolished and replaced with four unitary authorities. The Avon (Structural Change) Order 1995 was debated in the House of Commons on 22 February 1995.[16] The Order came into effect on 1 April 1996. The four authorities that replaced Avon are:

- The City and County of Bristol

- South Gloucestershire – formed from the Kingswood and Northavon districts.

- North Somerset – formed from the Woodspring district.

- Bath and North East Somerset – formed from the Bath and Wansdyke districts.

For ceremonial purposes, the post of Lord Lieutenant of Avon was abolished and Bristol regained its own Lord Lieutenant and High Sheriff, while the other authorities were returned to their traditional counties. Suggestions to alter Bristol's boundaries (either by drawing new boundaries or by merely incorporating the mostly urbanised borough of Kingswood into it) were rejected.

Legacy

The demise of the County of Avon was the focus of a BBC documentary called The End of Avon, produced by Linda Orr and Michael Lund and broadcast in 1996. In 2006, the BBC Somerset presenter Adam Thomas, in a BBC One regional programme Inside Out West, investigated why Avon refuses to die. Systems inertia means that the county continues to be included in the databases of large corporations as part of addresses in the area. Some private organisations such as the Avon Wildlife Trust choose to retain their name. The Royal Mail indicated that it is not necessary to include Avon (or any other postal county) as part of any address as it had abandoned their use in 1996.

Some public bodies still cover the area of the former county of Avon: for example, Avon Fire and Rescue Service, the Avon Coroner's District, Avon and Wiltshire Mental Health Partnership NHS Trust, the West of England Strategic Partnership, Intelligence West, and until 2006 the Avon Ambulance Service (now merged with the Gloucestershire and Wiltshire ambulance services to form the Great Western Ambulance Service). The former county and its southern neighbour form the area covered by Avon and Somerset Constabulary (governed by the Avon and Somerset Police and Crime Commissioner). Though there is no longer a single council, the four unitary authorities still co-operate on many aspects of policy, such as the Joint Local Transport Plan.[17] Currently, the term "West of England" is used by some organisations to refer to the former Avon area, such as the West of England Local Enterprise Partnership.[18]

The term CUBA, the "County (or Councils) that Used to Be Avon", was coined to refer to the Avon area after abolition of the county. The term Severnside is sometimes used as a substitute for "Avon",[19] although the term can also be used to refer to the stretch of shoreline from Avonmouth north to Aust, or from Newport to Chepstow. "Greater Bristol" is also used.[20]

The Forest of Avon is a community forest covering part of the area of the four local authorities. Other relics of Avon's existence include the Avon Cycleway (first designed and promoted by Cyclebag), an 85-mile (137 km) circular route on quiet roads and cycle paths, which was a precursor of the National Cycle Network. Also, Avon County Council helped fund Sustrans' first cycleway, the Bristol & Bath Railway Path.

In 2016 the government proposed that the four local authorities that replaced Avon come together in a West of England Combined Authority with a "metro mayor" who would oversee a new combined authority, to create a "Western Powerhouse" analogous to the government's Northern Powerhouse concept.[21][22]

See also

- List of Lord Lieutenants of Avon

- List of High Sheriffs of Avon

- List of Sites of Special Scientific Interest in Avon

External links

- Avon: the name that refuses to die

- West of England LEP: Economic Intelligence

- Avon Scouts

- Avon architecture Avon architecture, information on key buildings.

- Images of Avon at the English Heritage Archive

References

- ^ Local government in England and Wales: A Guide to the New System. London: HMSO. 1974. p. 28. ISBN 0-11-750847-0.

- ^ Whitaker's Concise Almanack 1995. London: J Whitaker and Sons. 1994. p. 549. ISBN 0-85021-247-2.

- ^ Registrar General's annual estimated figure mid-1973

- ^ Intelligence West: West of England Key Statistics, Autumn 2010

- ^ Rayfield, Jack (1985). Somerset & Avon. London: Cadogan. ISBN 0-947754-09-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "The Boundary Commission". Bristol Mercury and Daily Post. 27 March 1888. p. 8 – via British Newspaper Archive.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ "Greater Bristol". Bristol Mercury and Daily Post. 1 June 1888.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Greater Bristol". Bristol Mail and Daily Post. 17 August 1888.

- ^ Youngs, Frederic A. Jr. (1979). Guide to the Local Administrative Units of England, Vol. I: Southern England. London: royal Historical Society. ISBN 0-901050-67-9.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Report of the Local Government Boundary Commission for the year 1947

- ^ M.J. Wise, Review: The Future of Local Government in England: The Redcliffe-Maud Report, The Geographical Journal, Vol. 135, No. 4. (Dec., 1969), pp. 583–587 at JSTOR, accessed November 28, 2007

- ^ HMSO. Local Government in England: Government Proposals for Reorganisation. Cmnd. 4584

- ^ "Rural dwellers fight urban takeover". The Times. 3 November 1971. p. 5.

- ^ "Local Government Bill". Hansard 1803 – 2005. Parliament of the United Kingdom. 16 November 1971. Retrieved 18 February 2009.

- ^ "Somerset loses its battle to remain intact". The Times. 17 October 1972.

- ^ http://www.parliament.the-stationery-office.co.uk/pa/cm199495/cmhansrd/1995-02-22/Debate-14.html

- ^ B&NES, Bristol, North Somerset & South Gloucestershire Councils, 2005. Greater Bristol Joint Local Transport Plan 2006–2011

- ^ West of England Local Enterprise Partnership homepage. Retrieved 7 July 2013

- ^ See for example the renaming of the Avon Valuations Tribunal to Severnside, in 1996 SI 1996/43 Archived 5 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Study Area". Greater Bristol Strategic Transport Study. Archived from the original on 19 June 2004.

- ^ "West of England £1bn devolution deal announced in Budget". BBC News. 16 March 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ^ Gavin Thompson (16 March 2016). "Metro mayor and £1 billion investment for Greater Bristol announced in Budget 2016". Bristol Post. Retrieved 17 March 2016.