James Wolfe

James Wolfe | |

|---|---|

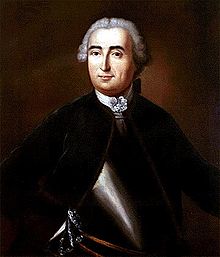

"Major General Wolfe. Who, at the Expence of his Life, purchased immortal Honour for his Country, and planted, with his own Hand, the British Laurel, in the inhospitable Wilds of North America, By the Reduction of Quebec, Septr. 13th. 1759." Portrait attributed to Joseph Highmore. | |

| Born | 2 January 1727 Westerham, Kent, England |

| Died | 13 September 1759 (aged 32) Plains of Abraham, Quebec, New France |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1740–1759 |

| Rank | Major-general |

| Commands | 20th Regiment of Foot |

| Battles / wars | |

| Relations | Lieutenant-general Edward Wolfe (father) |

| Signature | |

James Wolfe (2 January 1727 – 13 September 1759) was a British Army officer known for his training reforms and, as a major general, remembered chiefly for his victory in 1759 over the French at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in Quebec.

The son of a distinguished general, Edward Wolfe, he received his first commission at a young age and saw extensive service in Europe during the War of the Austrian Succession. His service in Flanders and in Scotland, where he took part in the suppression of the Jacobite Rebellion, brought him to the attention of his superiors. The advancement of his career was halted by the Peace Treaty of 1748 and he spent much of the next eight years on garrison duty in the Scottish Highlands. Already a brigade major at the age of 18, he was a lieutenant-colonel by 23.

The outbreak of the Seven Years' War in 1756 offered Wolfe fresh opportunities for advancement. His part in the aborted raid on Rochefort in 1757 led William Pitt to appoint him second-in-command of an expedition to capture the Fortress of Louisbourg. Following the success of the siege of Louisbourg he was made commander of a force which sailed up the Saint Lawrence River to capture Quebec City. After a long siege, Wolfe defeated a French force under the Marquis de Montcalm, allowing British forces to capture the city. Wolfe was killed at the height of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham due to injuries from three musket balls. The next day, Montcalm died as well.

Wolfe's part in the taking of Quebec in 1759 earned him lasting fame, and he became an icon of Britain's victory in the Seven Years' War and subsequent territorial expansion. He was depicted in the painting The Death of General Wolfe, which became famous around the world. Wolfe was posthumously dubbed "The Hero of Quebec", "The Conqueror of Quebec", and also "The Conqueror of Canada", since the capture of Quebec led directly to the capture of Montreal, ending French control of the colony.

Early life

[edit]

James Wolfe was born at the local vicarage on 2 January 1727 (New Style or 22 December 1726 Old Style) at Westerham, Kent, the older of two sons of Colonel (later Lieutenant General) Edward Wolfe,[1] a veteran soldier whose family was of Anglo-Irish origin, and the former Henrietta Thompson. His uncle was Edward Thompson MP, a distinguished politician. Wolfe's childhood home in Westerham, known in his lifetime as Spiers, has been preserved in his memory by the National Trust under the name Quebec House.[2] Wolfe's family were long settled in Ireland and he regularly corresponded with his uncle Major Walter Wolfe in Dublin. Stephen Woulfe, the distinguished Irish politician and judge of the next century, was from the Limerick branch of the same family; his father was James Wolfe's third cousin.

The Wolfes were close to the Warde family, who lived at Squerryes Court in Westerham. Wolfe's boyhood friend George Warde achieved fame as Commander-in-Chief in Ireland.

Around 1738, the family moved to Greenwich, in north-west Kent. From his earliest years, Wolfe was destined for a military career, entering his father's 1st Marine regiment as a volunteer at the age of thirteen.

Illness prevented him from taking part in a large expedition against Spanish-held Cartagena in 1740, and his father sent him home a few months later.[3] He missed what proved to be a disaster for the British forces at the Siege of Cartagena during the War of Jenkins' Ear, in which most of the expedition died from disease.[4]

War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748)

[edit]European War

[edit]In 1740 the War of the Austrian Succession broke out in Europe. Although initially Britain did not actively intervene, the presence of a sizable French army near the border of the Austrian Netherlands compelled the British to send an expedition to help defend the territory of their Austrian ally in 1742. James Wolfe was given his first commission as a second lieutenant in his father's regiment of Marines in 1741.

Early in the following year he transferred to the 12th Regiment of Foot, a British Army infantry regiment, and set sail for Flanders some months later where the British took up position in Ghent.[5] Here, Wolfe was promoted to Lieutenant and made adjutant of his battalion. His first year on the continent was a frustrating one as, despite rumours of a British attack on Dunkirk, they remained inactive in Flanders.[6]

In 1743, he was joined by his younger brother, Edward, who had received a commission in the same regiment.[7] That year the Wolfe brothers took part in an offensive launched by the British. Instead of moving southwards as expected, the British and their allies instead thrust eastwards into Southern Germany where they faced a large French army.[8] The army came under the personal command of George II[9] but in June he appeared to have made a catastrophic mistake which left the Allies trapped against the river Main and surrounded by enemy forces in "a mousetrap".[10]

Rather than contemplate surrender, George tried to rectify the situation by launching an attack on the French positions near the village of Dettingen. Wolfe's regiment was involved in heavy fighting, as the two sides exchanged volley after volley of musket fire. His regiment had suffered the highest casualties of any of the British infantry battalions, and Wolfe had his horse shot from underneath him.[11] Despite three French attacks the Allies managed to drive off the enemy, who fled through the village of Dettingen which was then occupied by the Allies. However, George failed to adequately pursue the retreating enemy, allowing them to escape.[12] In spite of this the Allies had successfully thwarted the French move into Germany, safeguarding the independence of Hanover.

Wolfe's regiment at Battle of Dettingen came to the attention of the Duke of Cumberland[13] who had been close to him during the battle when they came under enemy fire. A year later, he became a captain of the 45th Regiment of Foot. After the success of Dettingen, the 1744 campaign was another frustration as the Allies forces now led by George Wade failed to complete their objective of capturing Lille, fought no major battles, and returned to winter quarters at Ghent without anything to show for their efforts. Wolfe was left devastated when his brother Edward died, probably of consumption, that autumn.[14]

Wolfe's regiment was left behind to garrison Ghent, which meant they missed the Allied defeat at the Battle of Fontenoy in May 1745 during which Wolfe's former regiment suffered extremely heavy casualties. Wolfe's regiment was then summoned to reinforce the main Allied army, now under the command of the Duke of Cumberland. Shortly after they had departed Ghent, the town was suddenly attacked by the French who captured it and its garrison.[15] Having narrowly avoided becoming a French prisoner, Wolfe was now made a brigade major.

Jacobite rising

[edit]

In July 1745, Charles Stuart landed in Scotland in an attempt to regain the British throne for his father, the exiled James Stuart. In the initial stages of the 1745 Rising, the Jacobites captured Edinburgh and defeated government forces at the Battle of Prestonpans in September. This resulted in the recall of Cumberland, commander of the British army in Flanders and 12,000 troops, including Wolfe's regiment.[16]

On 8 November, the Jacobite army crossed into England, avoiding government forces at Newcastle by taking the western route via Carlisle.[17] They reached Derby before turning back on 6 December, largely due to lack of English support, and successfully returned to Scotland.[18] Wolfe was aide-de-camp to Henry Hawley, commander at Falkirk and fought at Culloden in April under Cumberland.[19]

A famous anecdote claims Wolfe refused an order to shoot a wounded Highland officer after Culloden, the person giving the order variously named as Cumberland or Hawley. There is certainly evidence to confirm Jacobite wounded were killed and Hawley was one of those who gave orders to that effect.[20] However, the claim that he refused such orders cannot be confirmed, while author and historian John Prebble refers to the killings as 'symptomatic of the army's general mood and behaviour.'[21] This included Wolfe; as leader of punitive raids after the battle, he wrote to a colleague that 'as few Highlanders are made prisoner as possible.'[22]

Return to the Continent

[edit]In January 1747 Wolfe returned to the Continent and the War of the Austrian Succession, serving under Sir John Mordaunt. The French had taken advantage of the absence of Cumberland's British troops and had made advances in the Austrian Netherlands including the capture of Brussels.[23][24]

The major French objective in 1747 was to capture Maastricht considered the gateway to the Dutch Republic. Wolfe was part of Cumberland's army, which marched to protect the city from the advancing French force under Marshal Saxe. On 2 July Wolfe participated in the Battle of Lauffeld, he was very badly wounded and received an official commendation for services to Britain. Lauffeld was the largest battle in terms of numbers in which Wolfe fought,[25] with the combined strength of both armies totalling over 140,000. Following their narrow victory at Lauffeld, the French captured Maastricht and seized the strategic fortress at Bergen-op-Zoom. Both sides remained poised for further offensives, but an armistice halted the fighting.

In 1748, aged 21 and with service in seven campaigns, Wolfe returned to Britain following the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle which ended the war. Under the treaty, Britain and France had agreed to exchange all captured territory and the Austrian Netherlands were returned to Austrian control.

Peacetime service (1748–1756)

[edit]Once home, he was posted to Scotland and garrison duty, and a year later was made a major, in which rank he assumed command of the 20th Regiment, stationed at Stirling. In 1750, Wolfe was confirmed as Lieutenant Colonel of the regiment.

Over the eight years that Wolfe was in Scotland, he wrote military pamphlets and became proficient in French as a result of several trips to Paris. Despite struggling with bouts of ill health suspected to be tuberculosis, he made an effort to keep himself mentally fit by teaching himself Latin and mathematics. When able to, Wolfe trained his body, especially pushing himself to improve his swordsmanship.[26]

In 1752, Wolfe was granted extended leave. Departing from Scotland, he first went to Ireland and stayed with his uncle in Dublin. He visited Belfast and toured the site of the Battle of the Boyne.[27] After a brief stop at his parents' house in Greenwich, he received permission from the Duke of Cumberland to go abroad, and crossed the English Channel to France. In Paris, he was frequently entertained by the British Ambassador, Earl of Albemarle, with whom he had served in Scotland in 1746. In addition to this, Albemarle arranged an audience for Wolfe with Louis XV. [26] He submitted an application to extend his leave so that he could witness a major military exercise conducted by the French army, but he was instead urgently ordered home. He rejoined his regiment in Glasgow. By 1754 Britain's declining relationship with France made a war imminent, and fighting broke out in North America between the two sides.

Desertion, especially in the face of the enemy had always officially been regarded as a capital offence. Wolfe laid particular stress on the importance of the death penalty and in 1755, he ordered that any soldier who broke ranks ("offers to quit his rank or offers to flag") should be instantly put to death by an officer or a sergeant.[28]

Seven Years' War (1756–63)

[edit]

In 1756, with the outbreak of open hostilities with France, Wolfe was promoted to Colonel. He was stationed in Canterbury, where his regiment had been posted to guard his home county of Kent against a French invasion threat. He was extremely dispirited by news of the loss of Minorca in June 1756, lamenting what he saw as the lack of professionalism amongst the British forces. Despite a widespread belief that French landing was imminent, Wolfe thought that it was unlikely his men would be called into action.[29] In spite of this, he trained them diligently and issued fighting instructions to his troops.

As the threat of invasion decreased, the regiment was marched to Wiltshire. Despite the initial setbacks of the war in Europe and North America, the British were now expected to take the offensive and Wolfe anticipated playing a major role in future operations. However, his health was beginning to decline, which led to suspicions that he was suffering, as his younger brother (Edward Wolfe 1728–1744) had, from consumption.[30] Many of his letters to his parents began to assume a slightly fatalistic note in which he talked of the likelihood of an early death.[31]

Rochefort

[edit]In 1757, Wolfe participated in the British amphibious assault on Rochefort, a seaport on the French Atlantic coast. A major naval descent, it was designed to capture the town, and relieve pressure on Britain's German allies who were under French attack in Northern Europe. Wolfe was selected to take part in the expedition partly because of his friendship with its commander, Sir John Mordaunt. In addition to his regimental duties, Wolfe also served as Quartermaster General for the whole expedition.[32] The force was assembled on the Isle of Wight and after weeks of delay finally sailed on 7 September.

The attempt failed as, after capturing an island offshore, the British made no attempt to land on the mainland and press on to Rochefort and instead withdrew home. While their sudden appearance off the French coast had spread panic throughout France, it had little practical effect. Mordaunt was court-martialed for his failure to attack Rochefort, although acquitted.[33] Nonetheless, Wolfe was one of the few military leaders who had distinguished himself in the raid – having gone ashore to scout the terrain, and having constantly urged Mordaunt into action.[34] He had at one point told the General that he could capture Rochefort if he was given just 500 men but Mordaunt refused him permission.[35] While Wolfe was irritated by the failure, believing that they should have used the advantage of surprise and attacked and taken the town immediately, he was able to draw valuable lessons about amphibious warfare that influenced his later operations at Louisbourg and Quebec.

As a result of his actions at Rochefort, Wolfe was brought to the notice of the Prime Minister, William Pitt the Elder. Pitt had determined that the best gains in the war were to be made in North America where France was vulnerable, and planned to launch an assault on French Canada. Pitt now decided to promote Wolfe over the heads of a number of senior officers.

Louisbourg

[edit]

On 23 January 1758, James Wolfe was appointed as a brigadier general, and sent with Major General Jeffrey Amherst in the fleet of Admiral Boscawen to lay siege to the Fortress of Louisbourg in New France (located in present-day Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia). Louisbourg stood near the mouth of the St Lawrence River, and its capture was considered essential to any attack on Canada from the east. An expedition the previous year had failed to seize the town, because of a French naval build-up. For 1758 Pitt sent a much larger Royal Navy force to accompany Amherst's troops. Wolfe distinguished himself in preparations for the assault, the initial landing and in the aggressive advance of siege batteries. The French capitulated in June of that year in the Siege of Louisbourg (1758). He then participated in the Expulsion of the Acadians in the Gulf of St. Lawrence Campaign (1758).

The British had initially planned to advance along the St Lawrence and attack Quebec that year, but the onset of winter forced them to postpone to the following year. Similarly a plan to capture New Orleans was rejected,[36] and Wolfe returned home to England. Wolfe's part in the taking of the town brought him to the attention of the British public for the first time. The news of the victory at Louisbourg was tempered by the failure of a British force advancing towards Montreal at the Battle of Carillon and the death of George Howe, a widely respected young general whom Wolfe described as "the best officer in the British Army".[37] He died at almost the same time as the French general.

Québec (1759)

[edit]Appointment

[edit]

As Wolfe had comported himself admirably at Louisbourg, William Pitt the Elder chose him to lead the British assault on Québec City the following year. Although Wolfe was given the local rank of major general while serving in Canada, in Europe he was still only a full colonel. Amherst had been appointed as Commander-in-Chief in North America, and he would lead a separate and larger force that would attack Canada from the south. He insisted on the choice of his friend, the Irish officer Guy Carleton as Quartermaster General and threatened to resign the command should his friend not have been chosen.[38] Once this was granted, he began making preparations for his departure. Pitt was determined to once again give operations in North America top priority, as he planned to weaken France's international position by sailing back to India.

Advance up the Saint Lawrence

[edit]Despite the large build-up of British forces in North America, the strategy of dividing the army for separate attacks on Canada meant that once Wolfe reached Quebec the French commander Louis-Joseph de Montcalm would have a local superiority of troops having raised large numbers of Canadian militia to defend their homeland.[39] The French had initially expected the British to approach from the east, believing the St Lawrence River was impassable for such a large force and had prepared to defend Quebec from the south and west. An intercepted copy of British plans gave Montcalm several weeks to improve the fortifications protecting Quebec from an amphibious attack by Wolfe.[40]

Montcalm's goal was to prevent the British from capturing Quebec, thereby maintaining a French foothold in Canada. The French government believed a peace treaty was likely to be agreed the following year and so they directed the emphasis of their own efforts towards victory in Germany and a planned invasion of Britain hoping thereby to secure the exchange of captured territories. For this plan to be successful Montcalm had only to hold out until the start of winter. Wolfe had a narrow window to capture Quebec during 1759 before the St Lawrence began to freeze, trapping his force.

Wolfe's army was assembled at Louisbourg. He expected to lead 12,000 men, but was greeted by only approximately 400 officers, 7,000 regular troops, and 300 gunners.[41] Wolfe's troops were supported by a fleet of 49 ships and 140 smaller craft led by Admiral Charles Saunders. Eager to begin the campaign, after several delays, he pushed ahead with only part of his force and left orders for further arrivals to be sent on up the St Lawrence after him.[42]

Siege

[edit]

The British army laid siege to the city for three months. During that time, Wolfe issued a written document, known as Wolfe's Manifesto, to the French-Canadian civilians, as part of his strategy of psychological intimidation. In March 1759, prior to arriving at Quebec, Wolfe had written to Amherst: "If, by accident in the river, by the enemy's resistance, by sickness, or slaughter in the army, or, from any other cause, we find that Quebec is not likely to fall into our hands (persevering however to the last moment), I propose to set the town on fire with shells, to destroy the harvest, houses and cattle, both above and below, to send off as many Canadians as possible to Europe and to leave famine and desolation behind me; belle résolution & très chrétienne; but we must teach these scoundrels to make war in a more gentleman like manner." This manifesto has widely been regarded as counter-productive as it drove many neutrally-inclined inhabitants to actively resist the British, swelling the size of the militia defending to Quebec to as many as 10,000.

After an extensive yet inconclusive bombardment of the city, Wolfe initiated a failed attack north of Quebec at Beauport, where the French were securely entrenched. As the weeks wore on the chances of British success lessened, and Wolfe grew despondent. Amherst's large force advancing on Montreal had made very slow progress, ruling out the prospect of Wolfe receiving any help from him.

Battle and subsequent death

[edit]

Wolfe then led 4,400 men in small boats on a very bold and risky amphibious landing at the base of the cliffs west of Quebec along the St. Lawrence River. His army, with two small cannons, scaled the 200-metre cliff from the river below early in the morning of 13 September 1759. They surprised the French under the command of the Marquis de Montcalm, who thought the cliff would be unclimbable, and had set his defences accordingly. Faced with the possibility that the British would haul more cannons up the cliffs and knock down the city's remaining walls, the French fought the British on the Plains of Abraham. They were defeated after fifteen minutes of battle, but when Wolfe began to move forward, he was shot thrice, once in the arm, once in the shoulder, and finally in the chest.[43]

Historian Francis Parkman describes the death of Wolfe:

They asked him [Wolfe] if he would have a surgeon; but he shook his head, and answered that all was over with him. His eyes closed with the torpor of approaching death, and those around sustained his fainting form. Yet they could not withhold their gaze from the wild turmoil before them, and the charging ranks of their companions rushing through the line of fire and smoke.

"See how they run," one of the officers exclaimed, as the French fled in confusion before the levelled bayonets.

"Who run?" demanded Wolfe, opening his eyes like a man aroused from sleep.

"The enemy, sir," was the reply; "they give way everywhere."

"Then," said the dying general, "tell Colonel River, to cut off their retreat from the bridge. Now, God be praised, I die contented," he murmured; and, turning on his side, he calmly breathed his last breath.[44]

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham caused the deaths of the top military commander on each side: Montcalm died the next day from his wounds. Wolfe's victory at Quebec enabled the Montreal Campaign against the French the following year. With the fall of that city, French rule in North America, outside of Louisiana and the tiny islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, came to an end.

Wolfe's body was returned to Britain on HMS Royal William and interred in the family vault in St Alfege Church, Greenwich alongside his father (who had died in March 1759). The funeral service took place on 20 November 1759, the same day that Admiral Hawke won the last of the three great victories of the "Wonderful Year" and the "Year of Victories" – Minden, Quebec and Quiberon Bay.[citation needed]

Character

[edit]Wolfe was renowned by his troops for being demanding on himself and on them. He was also known for carrying the same combat equipment as his infantrymen – a musket, cartridge box and bayonet – which was unusual for officers of the period. Although he was prone to illness, Wolfe was an active and restless figure. Amherst reported that Wolfe seemed to be everywhere at once. There was a story that when someone in the British Court branded the young Brigadier mad, King George II retorted, "Mad, is he? Then I hope he will bite some of my other generals."[45] A cultured man, before the Battle of the Plains of Abraham Wolfe is said by John Robison to have recited Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, containing the line "The paths of glory lead but to the grave" to his officers, adding: "Gentlemen, I would rather have written that poem than take Quebec tomorrow".[46][47]

After being stung by rejection, in a letter to his mother in 1751 he admitted he would probably never marry and stated that he believed people could easily live without marrying.[45] An apocryphal story was published after Wolfe's death saying that he had carried a locket portrait of Katherine Lowther, his supposed betrothed, with him to North America, and that he gave the locket to First Lieutenant John Jervis the night before he died. The story holds that Wolfe had a premonition of his own death in battle, and that Jervis faithfully returned the locket to Lowther.[48]

Legacy

[edit]

The inscription on the obelisk at Quebec City, erected to commemorate the battle on the Plains of Abraham once read: "Here Died Wolfe Victorious." In order to avoid offending French-Canadians it now simply reads: "Here Died Wolfe."[49] Wolfe's defeat of the French led to the British capture of the New France department of Canada, and his "hero's death" made him a legend in his homeland. The Wolfe legend led to the famous painting The Death of General Wolfe by Benjamin West, the Anglo-American folk ballad "Brave Wolfe"[50] (sometimes known as "Bold Wolfe"), and the opening line of the patriotic Canadian anthem "The Maple Leaf Forever".

In 1792, scant months after the partition of Quebec into the provinces of Upper Canada and Lower Canada, the lieutenant-governor of the former, John Graves Simcoe, named the archipelago at the entrance to the St. Lawrence River for the victorious generals: Wolfe Island, Amherst Island, Howe Island, Carleton Island and Gage Island, for Thomas Gage. The last is now known as Simcoe Island.

In 1832, the first war monument in present-day Canada was erected on the site where Wolfe purportedly fell. The site is marked by a column surmounted by a helmet and sword. An inscription at its base reads, in French and English, "Here died Wolfe – 13 September 1759." It replaces a large stone which had been placed there by British troops to mark the spot.

Wolfe's Landing National Historic Site of Canada is located in Kennington Cove, on the east coast of Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. Contained entirely within the Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site of Canada, the site is bounded by a rocky beach to the south, and a rolling landscape of grasses and forest to the north, east and west. It was from this site that, during the Seven Years' War, British forces launched their successful attack on the French forces at Louisbourg. Wolfe's Landing was designated a national historic site of Canada in 1929 because: "here, on 8 June 1758, the men of Brigadier General James Wolfe's brigade made their successful landing, leading to the capitulation of Louisbourg".[51][52]

There is a memorial to Wolfe in Westminster Abbey by Joseph Wilton. The 3rd Duke of Richmond, who had served in Wolfe's regiment in 1753, commissioned a bust of Wolfe from Wilton. There is an oil painting "Placing the Canadian Colours on Wolfe's Monument in Westminster Abbey" by Emily Warren in Currie Hall at the Royal Military College of Canada.

A statue of Wolfe overlooks the Royal Naval College in Greenwich, a spot which has become increasingly popular for its panoramic views of London. A statue also graces the green in his native Westerham, Kent, alongside one of that village's other famous resident, Sir Winston Churchill. At Stowe Gardens in Buckinghamshire there is an obelisk, known as Wolfe's obelisk, built by the family that owned Stowe as Wolfe spent his last night in England at the mansion. Wolfe is buried under the Church of St Alfege, Greenwich, where there are four memorials to him: a replica of his coffin plate in the floor; The Death of Wolfe, a painting completed in 1762 by Edward Peary; a wall tablet; and a stained glass window. In addition the local primary school is named after him. The house in Greenwich where he lived, Macartney House, has an English Heritage blue plaque with his name on, and a nearby road is named General Wolfe Road after him.[53]

In 1761, as a perpetual memorial to Wolfe, George Warde, a friend of Wolfe's from boyhood, instituted the Wolfe Society, which to this day meets annually in Westerham for the Wolfe Dinner to his "Pious and Immortal Memory". Warde paid Benjamin West to paint "The Boyhood of Wolfe" which used to hang at Squerres Court but has recently been donated to the National Trust and is now hung at Quebec House his childhood home in Westerham. Warde also erected a cenotaph in Squerres Park to mark the place where Wolfe had received his first commission while visiting the Wardes.

There are several institutions, localities, thoroughfares, and landforms named in honour of him in Canada. Significant monuments to Wolfe in Canada exist on the Plains of Abraham where he fell, and near Parliament Hill in Ottawa. Ontario Governor John Graves Simcoe named Wolfe Island, an island in Lake Ontario and the Saint Lawrence River off the coast of Kingston (near the Royal Military College of Canada) in Wolfe's honour in 1792. On 13 September 2009, the Wolfe Island Historical Society led celebrations on the occasion of the 250th anniversary of James Wolfe's victory at Quebec. A life-size statue in Wolfe's likeness is to be sculpted.[49]

South Mount Royal Park, Calgary is home to a James Wolfe statue since 2009,[54] but it was originally located in Exchange Court in New York City.[55][56] It was sculpted in 1898 by John Massey Rhind and moved into storage around 1945 to 1950, sold in 1967 and relocated to Centennial Planetarium in Calgary, stored 2000 to 2008 and finally installed again in 2009.[56]

A senior girls house at the Duke of York's Royal Military School is named after Wolfe, where all houses are named after prominent figures of the military. There is a James Wolfe school for children aged 5–11 down the hill from his house in Greenwich, in Chesterfield Walk, which is just east of General Wolfe Road.

His letters home from the age of 13 until his death[57] as well as his copy of Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard and other items are housed at the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library in Toronto, Ontario.[58] Other artefacts and relics owned by Wolfe are held at museums in both Canada and England, although some have mainly legendary association. Wolfe's cloak worn at Louisbourg, Quebec and at the Plains of Abraham is part of the British Royal Collection. In 2008 it was lent to the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax, Nova Scotia for an exhibit on the Siege of Louisbourg, and in 2009 was loaned to the Army Museum at the Halifax Citadel where it remains on display. Wolfe Crescent, Halifax, Nova Scotia is named after Wolfe.

Point Wolfe is a former village and current campground located in Fundy National Park, which additionally contains the Point Wolfe Bridge.[59] The town of Wolfeboro, New Hampshire is named in honour of Wolfe. In Montreal, Rue Wolfe parallels Rue Montcalm and Rue Amherst, while in the Quebec City neighbourhood of Ste-Foy, he has given his name to an avenue.

Arms

[edit]

|

See also

[edit]- General Wolfe's Song

- The Maple Leaf Forever – another Canadian song glorifying General Wolfe.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Salmon, Edward (1909). Hutton, W. H. (ed.). General Wolfe. Makers of National History. Cassell & Company. pp. 1–2.

- ^ "Lieut. General James Wolfe". The Weald of Kent, Surrey, and Sussex. Archived from the original on 4 January 2009. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ^ Stacey, C. P. (1974). "Wolfe, James". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. III (1741–1770) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Browning, Reed (1994). The War of the Austrian Succession. St. Martin's Press. pp. 59–61. ISBN 978-0-312-12561-5.

- ^ * Brumwell, Stephen (2006). Paths of Glory: The Life and Death of General James Wolfe. Continuum. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-1-85285-553-6.

- ^ Brumwell (2006), pp. 24–25.

- ^ Brumwell (2006), p. 25.

- ^ Browning (1994), pp. 134–135.

- ^ Trench, Charles Chenevix (1973). George II. Allen Lane. pp. 217–218. ISBN 978-0-7139-0481-9.

- ^ Brumwell (2006), pp. 26–27.

- ^ Brumwell (2006), pp. 29–31.

- ^ Browning (1994), pp. 139–140.

- ^ Pocock, Tom (1998). Battle for Empire: The Very First World War 1756–63. Michael O'Mara Books. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-85479-390-4.

- ^ Brumwell (2006), pp. 35–36.

- ^ Brumwell (2006), pp. 36–37.

- ^ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites: A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. p. 195. ISBN 978-1408819128.

- ^ Brumwell (2006), pp. 42–43.

- ^ Pittock, Murray (1998). Jacobitism. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 115. ISBN 978-0333667989.

- ^ Riding, p. 346

- ^ Royle, Trevor (2016). Culloden; Scotland's Last Battle and the Forging of the British Empire. Little, Brown. p. 99. ISBN 978-1408704011.

- ^ Prebble, John (1963). Culloden (2002 ed.). Pimlico. p. 203. ISBN 978-0712668200.

- ^ Royle, p.119

- ^ Browning (1994), pp. 259–260.

- ^ Brumwell (2006), pp. 57–58.

- ^ Brumwell (2006), pp. 58–63.

- ^ a b Brumwell (2006), pp. 93–97.

- ^ Brumwell (2006), pp. 92–93.

- ^ Keegan, John; Holmes, Richard (1986). Soldiers: A History of Men in Battle. Viking. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-670-80969-1.

- ^ Brumwell (2006), pp. 111–115.

- ^ Landry, Peter (2011). "James Wolfe (1727–1759)". Early Nova Scotians: 1600–1867. BluPete.

- ^ Brumwell (2006), p. 106.

- ^ Corbett, Julian S. (1907). England in the Seven Years' War: a study in combined strategy. Vol. I. Longmans, Green, and Co. p. 202.

- ^ Black, Jeremy (1992). Pitt the Elder. Cambridge University Press. p. 171. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511560354. ISBN 978-0-5115-6035-4.

- ^ Johnston, A. J. B. (2007). Endgame 1758: The Promise, the Glory, and the Despair of Louisbourg's Last Decade. University of Nebraska Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-8032-0986-2.

- ^ Stanhope, Philip Henry (1844). History of England from the peace of Utrecht to the peace of Versailles, 1713–1783. Vol. IV. J. Murray. p. 110.

- ^ Brown p. 165[full citation needed]

- ^ Pocock (1998), p. 95.

- ^ Nelson, Paul David (2000). General Sir Guy Carleton, Lord Dorchester: Soldier-statesman of Early British Canada. Associated University Presses. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8386-3838-5.

- ^ Dull pp. 144–145[full citation needed]

- ^ Dull pp. 142–146[full citation needed]

- ^ Reid, Stuart (2000). Wolfe: The Career of General James Wolfe from Culloden to Quebec. Spellmount. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-86227-084-8.

- ^ Snow, Dan (2009). Death or Victory: The Battle for Quebec and the Birth of Empire. HarperCollins. pp. 21–30. ISBN 978-0-00-734295-2.

- ^ Parkman (1885), pp. 296–297.

- ^ Parkman (1885), pp. 296–297.

- ^ a b Parkman (1885).

- ^ Colombo, John (1984), Canadian Literary Landmarks, Hounslow Press, p. 93

- ^ Morris, Edward E. (January 1900). "Wolfe and Gray's 'Elegy'". The English Historical Review. 15 (57): 125–129. JSTOR 548418.

- ^ Crimmin, P. K. (2000). "John Jervis, Earl of St Vincent – 1735–1823". In Le Fevre, Peter; Harding, Richard (eds.). Precursors of Nelson: British Admirals of the Eighteenth Century. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-2901-7.

- ^ a b Stewart, Victoria M. (22 September 2008). "Wolfe celebrations set for 2009". Kingston Whig-Standard. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- ^ "Brave Wolfe". Dulcimer Players News. Archived from the original on 25 July 2006. Retrieved 21 October 2007.

- ^ Wolfe's Landing National Historic Site of Canada. Canadian Register of Historic Places.

- ^ Wolfe's Landing National Historic Site of Canada. Directory of Federal Heritage Designations. Parks Canada.

- ^ Williams, Guy R. (1975). London in the country: the growth of suburbia. Hamilton. p. 85. ISBN 9780241891933.

- ^ Finch, David (6 September 2009). "Wolfe rises on anniversary of his death". Calgary Herald. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "Where They are is Known; Why They Went, Isn't". The New York Times. 1 April 2007.

- ^ a b "General Wolfe – Calgary, Alberta". Waymarking.com. 9 July 2012.

- ^ "U of T Libraries Acquire General James Wolfe's Historic Letters". Fisher Library. University of Toronto. 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ^ Brown, Ian (26 March 2017). "Inside old-school books, every scribble tells a story". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ "Point Wolfe campground". Fundy National Park. Parks Canada. 18 September 2017.

- ^ Herbert George Todd (1915). Armory and lineages of Canada. p. 124.

General References

[edit]- "James Wolfe". The Canadian Encyclopedia (online ed.). Historica Canada. 27 March 2015.

- Hampson, Sarah (25 March 2017). "Archive of General Wolfe's personal letters is coming to Canada". The Globe and Mail.

- Lloyd, Ernest Marsh (1900). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 62. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 296–304.

Further reading

[edit]- Adair, E. R. (1936). "Military Reputation of Major-General James Wolfe". Report of the Annual Meeting. 15. Canadian Historical Association: 7–31. doi:10.7202/300153ar. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2013.

- Anderson, Fred (2000). Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766. Knopf Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-307-42539-3.

- Bell, Andrew (1859). British-Canadian Centennium, 1759–1859: General James Wolfe, His Life and Death: [...] being the Anniversary Day of the Battle of Quebec, fought a Century before in which Britain lost a Hero and Won a Province. Quebec: J. Lovell. pp. 52. ISBN 9780665441615.

- Bradley, Arthur Granville (1895). Wolfe. London: Macmillan and Company.

- Burpee, Lawrence J. (1926). "Wolfe, James". The Oxford Encyclopaedia of Canadian History. London & Toronto: Oxford University Press. pp. 690–691.

- Brown, Ian (26 March 2017). "In Wolfe's clothing". The Globe and Mail.

- Carroll, Joy (2004). Wolfe & Montcalm: Their Lives, Their Times and the Fate of a Continent. Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-55297-905-1.

- Carroll, Joy (2006). Wolfe et Montcalm : la véritable histoire de deux chefs ennemis [Wolfe and Montcalm: the True Story of Two Enemy Leaders] (in French). trans. Suzanne Anfossi. Montréal: Éditions de l'Homme. ISBN 2-7619-2192-5.

- Casgrain, P. B. (1904). La maison de Borgia, premier poste de Wolfe à la bataille des Plaines d'Abraham: où était-elle située (in French). Ottawa: Chez Hope & Fils. pp. 45–62.[permanent dead link]

- Casgrain, Henri-Raymond (1905). Wolfe and Montcalm. The Makers of Canada. Vol. IV. Toronto: Morang & Co.

- Chartrand, René (2000). Louisbourg 1758: Wolfe's First Siege. Bloomsbury USA. ISBN 978-1-84176-217-3.

- Clarke, John Mason (1911). Results of Excavations at the Site of the French "Custom House" or "General Wolfe's House" on Peninsula Point in Gaspe Bay. Montréal: C. A. Marchand.

- Doughty, A. (1901). The Siege of Quebec and the battle of the Plains of Abraham. Vol. First Volume. Quebec: Dussault & Proulx.; Also Second Volume; Third Volume; Fourth Volume; Fifth Volume; Sixth Volume

- Grove of Richmond (1759). A letter to a Right Honourable Patriot: [...]. London: J. Burd. ISBN 9780665382581.

- Hibbert, Christopher (1999) [1959]. Wolfe at Quebec: The Man Who Won the French and Indian War. Cooper Square Press. ISBN 978-0-8154-1016-4.

- Le Jeune, Louis (1931). "James Wolfe". Dictionnaire Général de biographie, histoire, littérature, agriculture, commerce, industrie et des arts, sciences, moeurs, coutumes, institutions politiques et religieuses du Canada (in French). Vol. 2. Ottawa: Université d'Ottawa. pp. 818–821.

- MacLeod, D. Peter (2008). Northern Armageddon: The Battle of the Plains of Abraham and the Making of the American Revolution. Knopf Doubleday. ISBN 978-1-101-94695-4.

- Mauduit, Israel (1765). An Apology for the Life and Actions of General Wolfe: Against the Misrepresentations in a Pamphlet, called, A Counter Address to the Public, with some other Remarks on that Performance. London. ISBN 9780665368660.

- McNairn, Alan (1997). Behold the Hero: General Wolfe and the Arts in the Eighteenth Century. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-1539-0.

- Parkman, Francis (1884). Montcalm and Wolfe. Vol. I. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

- Parkman, Francis (1885). Montcalm and Wolfe. Vol. II. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

- Pringle, John (1760). Life of General James Wolfe, the conqueror of Canada. London: G. Kearsly.

- Reilly, Robin (2001) [1960]. Wolfe of Quebec (reprint ed.). Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-35838-0.

- Sabine, Lorenzo (1859). An Address Before the New England Historic-Genealogical Society [...]: The hundredth anniversary of the death of Major General James Wolfe [...]. Boston: A. Williams & Co.

- Stacey, Charles Perry (1959). Quebec, 1759: the siege and the battle. Macmillan.

- Sutherland, John Campbell (1926). General Wolfe. Toronto: Ryerson Press.

- Wallace, W. Stewart, ed. (1948). "James Wolfe". The Encyclopedia of Canada. Vol. VI. Toronto: University Associates of Canada. pp. 315–316.

- Warner, Oliver (1972). With Wolfe to Quebec: the Path to Glory. Collins. ISBN 9780002119429.

- Waugh, William Templeton (1928). James Wolfe, Man and Soldier. Montreal: L. Carrier & co.

- Webster, John Clarence (1925). A Study of the Portraiture of James Wolfe. Ottawa: Royal Society of Canada. pp. 47–65.

- Whitton, Frederick Ernest (1929). Wolfe and North America. Little, Brown & Company.

- Willson, Beckles (1909). The Life and Letters of James Wolfe. London: William Heinemann.

- Wolfe-Aylward, Annie Elizabeth Chenells (1926). The Pictorial Life of Wolfe. Plymouth, England: William Brendon and son.

- Wright, Robert (1864). The Life of Major-General James Wolfe. London: Chapman and Hall.

- Wolfe: Portraiture and Genealogy. London: Permanent Advisory Committee of Quebec House. 1959.

- Wood, William (1915). The Winning of Canada: A Chronicle of Wolfe. Toronto: Glasgow, Brook & Co.

External links

[edit]- Works by or about James Wolfe at the Internet Archive

- Works by James Wolfe at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Battle of Montmorency National Historic Event. Directory of Federal Heritage Designations. Parks Canada.

- Unknown. "History and Chronology of James Wolfe Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine", in World History Database

- Wolfe, James: Collection of letters at Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library.

- "Wolfiana". Archives & Research Library, New Brunswick Museum. New Brunswick Museum. 2003. Archived from the original on 13 March 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- New Brunswick Museum. "A National Treasure in New Brunswick: James Barry's Death of General Wolfe", in New Brunswick Museum (Web site), 2003

- NBC. Plains of Abraham Web site, Government of Canada. (National Battlefields Commission)

- NBC. 1759: From the Warpath to the Plains of Abraham, Virtual Museum Canada, The National Battlefields Commission, 2005

- Archives of James Wolfe (James Wolfe collection, R4770) are held at Library and Archives Canada

- 1727 births

- 1759 deaths

- Anglophone Quebec people

- British Army major generals

- British military personnel killed in the Seven Years' War

- British Army personnel of the War of the Austrian Succession

- British Army personnel of the Jacobite rising of 1745

- British Army personnel of the French and Indian War

- People from Westerham

- Lancashire Fusiliers officers

- Suffolk Regiment officers

- Military personnel from Kent

- Sherwood Foresters officers

- 67th Regiment of Foot officers