S100A9

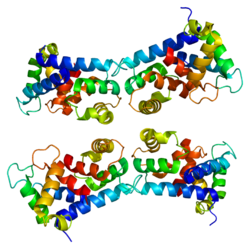

S100 calcium-binding protein A9 (S100A9) also known as migration inhibitory factor-related protein 14 (MRP14) or calgranulin B is a protein that in humans is encoded by the S100A9 gene.[5]

The proteins S100A8 and S100A9 form a heterodimer called calprotectin.

Function

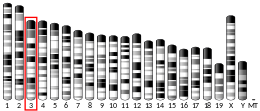

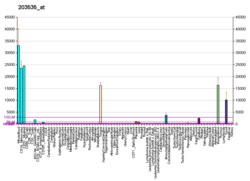

[edit]S100A9 is a member of the S100 family of proteins containing 2 EF hand calcium-binding motifs. S100 proteins are localized in the cytoplasm and/or nucleus of a wide range of cells, and involved in the regulation of a number of cellular processes such as cell cycle progression and differentiation. S100 genes include at least 13 members which are located as a cluster on chromosome 1q21. This protein may function in the inhibition of casein kinase.[5]

MRP14 complexes with MRP-8 (S100A8), another member of the S100 family of calcium-modulated proteins; together, MRP8 and MRP14 regulate myeloid cell function by binding to Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)[6][7] and the receptor for advanced glycation end products.[8]

Intracellular S100A9 alters mitochondrial homeostasis within neutrophils. As a result, neutrophils lacking S100A9 produce higher levels of mitochondrial superoxide and undergo elevated levels of suicidal NETosis in response to bacterial pathogens. [9] Furthermore, S100A9-deficient mice are protected from systemic Staphylococcus aureus infections with lower bacterial burdens in the heart, which suggests an organ-specific function for S100A9. [9][10]

Clinical significance

[edit]Altered expression of the S100A9 protein is associated with the disease cystic fibrosis.[5]

MRP-8/14 broadly regulates vascular inflammation and contributes to the biological response to vascular injury by promoting leukocyte recruitment.[11]

MRP-8/14 also regulates vascular insults by controlling neutrophil and macrophage accumulation, macrophage cytokine production, and SMC proliferation. The above study has shown therefore the deficiency of MRP-8 and MRP-14 reduces neutrophil- and monocyte-dependent vascular inflammation and attenuates the severity of diverse vascular injury responses in vivo. MRP-8/14 may be a useful biomarker of platelet and inflammatory disease activity in atherothrombosis and may serve as a novel target for therapeutic intervention.[12] Also, the platelet transcriptome reveals quantitative differences between acute and stable coronary artery disease. MRP-14 expression increases before ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction, (STEMI), and increasing plasma concentrations of MRP-8/14 among healthy individuals predict the risk of future cardiovascular events.[13]

S100A9 (myeloid-related protein 14, MRP 14 or calgranulin B) has been implicated in the abnormal differentiation of myeloid cells in the stroma of cancer, and to leukemia progression.[14][15] This contributes to creating an overall immunosuppressive microenvironment that may contribute to the inability of a protective or therapeutic cellular immune response to be generated by the tumor-bearing host. Outside of malignancy, S100A9 in association with its dimerization partner, S100A8 (MRP8 or calgranulin A) signals for lymphocyte recruitment in sites of inflammation.[16] S100A9/A8 (synonyma: Calgranulin A/B; Calprotectin) are also regarded as marker proteins for a number of inflammatory diseases in humans, especially in rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Myeloid-related protein (MRP)-8 is an inflammatory protein found in several mucosal secretions. In cervico-vaginal secretions MRP-8 can stimulate HIV production;[17] and thus might be involved in sexual transmission of HIV, as well as other sexually transmitted diseases (STD). In Vitro studies have shown that HIV-inducing of recombinant MRP-8 can increase HIV expression by up to 40-fold.[17]

Animal studies

[edit]A S100A9 knockout mouse has (a mouse mutant, that is deficient of S100A9) been constructed. This mouse is fertile, viable and healthy. However, expression of S100A8 protein, the dimerization partner of S100A9, is also absent in these mice in differentiated myeloid cells.[18] This mouse line has been used to study the role of S100A9 and S100A8 in a number of experimental inflammatory conditions.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000163220 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000056071 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b c "Entrez Gene: S100A9 S100 calcium binding protein A9".

- ^ Vogl T, Tenbrock K, Ludwig S, Leukert N, Ehrhardt C, van Zoelen MA, Nacken W, Foell D, van der Poll T, Sorg C, Roth J (September 2007). "Mrp8 and Mrp14 are endogenous activators of Toll-like receptor 4, promoting lethal, endotoxin-induced shock". Nat. Med. 13 (9): 1042–9. doi:10.1038/nm1638. PMID 17767165. S2CID 9086391.

- ^ Ibrahim ZA, Armour CL, Phipps S, Sukkar MB (2013). "RAGE and TLRs: relatives, friends or neighbours?". Molecular Immunology. 56 (4): 739–44. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2013.07.008. PMID 23954397.

- ^ Boyd JH, Kan B, Roberts H, Wang Y, Walley KR (May 2008). "S100A8 and S100A9 mediate endotoxin-induced cardiomyocyte dysfunction via the receptor for advanced glycation end products". Circ. Res. 102 (10): 1239–46. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.167544. PMID 18403730.

- ^ a b Monteith AJ, Miller JM, Maxwell CN, Chazin WJ, Skaar EP (September 2021). "Neutrophil extracellular traps enhance macrophage killing of bacterial pathogens". Science Advances. 7 (37): eabj2101. Bibcode:2021SciA....7.2101M. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abj2101. PMC 8442908. PMID 34516771.

- ^ Juttukonda LJ, Berends ET, Zackular JP, Moore JL, Stier MT, Zhang Y, et al. (October 2017). "Dietary Manganese Promotes Staphylococcal Infection of the Heart". Cell Host & Microbe. 22 (4): 531–542.e8. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2017.08.009. PMC 5638708. PMID 28943329.

- ^ Croce K, Gao H, Wang Y, Mooroka T, Sakuma M, Shi C, Sukhova GK, Packard RR, Hogg N, Libby P, Simon DI (August 2009). "MRP-8/14 is Critical for the Biological Response to Vascular Injury". Circulation. 120 (5): 427–36. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.814582. PMC 3070397. PMID 19620505.

- ^ Morrow DA, Wang Y, Croce K, Sakuma M, Sabatine MS, Gao H, Pradhan AD, Healy AM, Buros J, McCabe CH, Libby P, Cannon CP, Braunwald E, Simon DI (January 2008). "Myeloid-Related Protein-8/14 and the Risk of Cardiovascular Death or Myocardial Infarction after an Acute Coronary Syndrome in the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 Trial". Am. Heart J. 155 (1): 49–55. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2007.08.018. PMC 2645040. PMID 18082488.

- ^ Healy AM, Pickard MD, Pradhan AD, Wang Y, Chen Z, Croce K, Sakuma M, Shi C, Zago AC, Garasic J, Damokosh AI, Dowie TL, Poisson L, Lillie J, Libby P, Ridker PM, Simon DI (May 2006). "Platelet expression profiling and clinical validation of myeloid-related protein-14 as a novel determinant of cardiovascular events". Circulation. 113 (19): 2278–84. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.607333. PMID 16682612.

- ^ Cheng P, Corzo CA, Luetteke N, Yu B, Nagaraj S, Bui MM, Ortiz M, Nacken W, Sorg C, Vogl T, Roth J, Gabrilovich DI (September 2008). "Inhibition of dendritic cell differentiation and accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer is regulated by S100A9 protein". J. Exp. Med. 205 (10): 2235–49. doi:10.1084/jem.20080132. PMC 2556797. PMID 18809714.

- ^ Prieto D, Sotelo N, Seija N, Sernbo S, Abreu C, Durán R, et al. (2017). "S100-A9 protein in exosomes from chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells promotes NF-κB activity during disease progression". Blood. 130 (6): 777–788. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-02-769851. hdl:20.500.12008/31377. PMID 28596424.

- ^ Hiratsuka S, Watanabe A, Aburatani H, Maru Y (December 2006). "Tumour-mediated upregulation of chemoattractants and recruitment of myeloid cells predetermines lung metastasis". Nat. Cell Biol. 8 (12): 1369–75. doi:10.1038/ncb1507. PMID 17128264. S2CID 36876191.

- ^ a b Hashemi FB, Mollenhauer J, Madsen LD, Sha BE, Nacken W, Moyer MB, Sorg C, Spear GT (2001). "Myeloid-related protein (MRP)-8 from cervico-vaginal secretions activates HIV replication". AIDS. 15 (4): 441–9. doi:10.1097/00002030-200103090-00002. PMID 11242140. S2CID 38638273.

- ^ Manitz MP, Horst B, Seeliger S, Strey A, Skryabin BV, Gunzer M, Frings W, Schönlau F, Roth J, Sorg C, Nacken W (February 2003). "Loss of S100A9 (MRP14) Results in Reduced Interleukin-8-Induced CD11b Surface Expression, a Polarized Microfilament System, and Diminished Responsiveness to Chemoattractants In Vitro". Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 (3): 1034–43. doi:10.1128/MCB.23.3.1034-1043.2003. PMC 140712. PMID 12529407.

Further reading

[edit]- Schäfer BW, Heizmann CW (1996). "The S100 family of EF-hand calcium-binding proteins: functions and pathology". Trends Biochem. Sci. 21 (4): 134–40. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(96)80167-8. PMID 8701470.

- Kerkhoff C, Klempt M, Sorg C (1999). "Novel insights into structure and function of MRP8 (S100A8) and MRP14 (S100A9)". Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1448 (2): 200–11. doi:10.1016/S0167-4889(98)00144-X. PMID 9920411.

- Nacken W, Roth J, Sorg C, Kerkhoff C (2003). "S100A9/S100A8: Myeloid representatives of the S100 protein family as prominent players in innate immunity". Microsc. Res. Tech. 60 (6): 569–80. doi:10.1002/jemt.10299. PMID 12645005. S2CID 10145841.

- Rasmussen HH, van Damme J, Puype M, et al. (1993). "Microsequences of 145 proteins recorded in the two-dimensional gel protein database of normal human epidermal keratinocytes". Electrophoresis. 13 (12): 960–9. doi:10.1002/elps.11501301199. PMID 1286667. S2CID 41855774.

- Longbottom D, Sallenave JM, van Heyningen V (1992). "Subunit structure of calgranulins A and B obtained from sputum, plasma, granulocytes and cultured epithelial cells". Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1120 (2): 215–22. doi:10.1016/0167-4838(92)90273-G. PMID 1562590.

- Dorin JR, Emslie E, van Heyningen V (1991). "Related calcium-binding proteins map to the same subregion of chromosome 1q and to an extended region of synteny on mouse chromosome 3". Genomics. 8 (3): 420–6. doi:10.1016/0888-7543(90)90027-R. PMID 2149559.

- Edgeworth J, Freemont P, Hogg N (1989). "Ionomycin-regulated phosphorylation of the myeloid calcium-binding protein p14". Nature. 342 (6246): 189–92. Bibcode:1989Natur.342..189E. doi:10.1038/342189a0. PMID 2478889. S2CID 4310792.

- Murao S, Collart FR, Huberman E (1989). "A protein containing the cystic fibrosis antigen is an inhibitor of protein kinases". J. Biol. Chem. 264 (14): 8356–60. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)83189-1. PMID 2656677.

- Odink K, Cerletti N, Brüggen J, et al. (1987). "Two calcium-binding proteins in infiltrate macrophages of rheumatoid arthritis". Nature. 330 (6143): 80–2. Bibcode:1987Natur.330...80O. doi:10.1038/330080a0. PMID 3313057. S2CID 4366579.

- Lagasse E, Clerc RG (1988). "Cloning and expression of two human genes encoding calcium-binding proteins that are regulated during myeloid differentiation". Mol. Cell. Biol. 8 (6): 2402–10. doi:10.1128/mcb.8.6.2402. PMC 363438. PMID 3405210.

- Schäfer BW, Wicki R, Engelkamp D, et al. (1995). "Isolation of a YAC clone covering a cluster of nine S100 genes on human chromosome 1q21: rationale for a new nomenclature of the S100 calcium-binding protein family". Genomics. 25 (3): 638–43. doi:10.1016/0888-7543(95)80005-7. PMID 7759097.

- Engelkamp D, Schäfer BW, Mattei MG, et al. (1993). "Six S100 genes are clustered on human chromosome 1q21: identification of two genes coding for the two previously unreported calcium-binding proteins S100D and S100E". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90 (14): 6547–51. Bibcode:1993PNAS...90.6547E. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.14.6547. PMC 46969. PMID 8341667.

- Roth J, Burwinkel F, van den Bos C, et al. (1993). "MRP8 and MRP14, S-100-like proteins associated with myeloid differentiation, are translocated to plasma membrane and intermediate filaments in a calcium-dependent manner". Blood. 82 (6): 1875–83. doi:10.1182/blood.V82.6.1875.1875. PMID 8400238.

- Miyasaki KT, Bodeau AL, Murthy AR, Lehrer RI (1993). "In vitro antimicrobial activity of the human neutrophil cytosolic S-100 protein complex, calprotectin, against Capnocytophaga sputigena". J. Dent. Res. 72 (2): 517–23. doi:10.1177/00220345930720020801. PMID 8423249. S2CID 8311930.

- Newton RA, Hogg N (1998). "The human S100 protein MRP-14 is a novel activator of the beta 2 integrin Mac-1 on neutrophils". J. Immunol. 160 (3): 1427–35. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.160.3.1427. PMID 9570563. S2CID 26179608.

- Vogl T, Pröpper C, Hartmann M, et al. (1999). "S100A12 is expressed exclusively by granulocytes and acts independently from MRP8 and MRP14". J. Biol. Chem. 274 (36): 25291–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.36.25291. PMID 10464253.

- Kerkhoff C, Klempt M, Kaever V, Sorg C (2000). "The two calcium-binding proteins, S100A8 and S100A9, are involved in the metabolism of arachidonic acid in human neutrophils". J. Biol. Chem. 274 (46): 32672–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.46.32672. PMID 10551823.

- Stulík J, Koupilova K, Osterreicher J, et al. (2000). "Protein abundance alterations in matched sets of macroscopically normal colon mucosa and colorectal carcinoma". Electrophoresis. 20 (18): 3638–46. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19991201)20:18<3638::AID-ELPS3638>3.0.CO;2-W. PMID 10612291. S2CID 21186044.