Canonization of Joan of Arc

Saint Joan of Arc | |

|---|---|

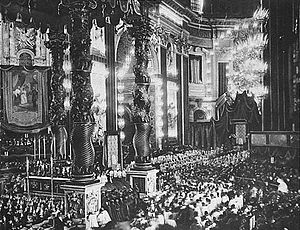

Canonization Mass of Joan of Arc in Saint Peter's Basilica. | |

| Virgin, Mystic, and Martyr | |

| Born | 6 January, c. 1412 [1] Domrémy, Duchy of Bar, France.[2] |

| Died | 30 May 1431 (aged approx. 19) Rouen, Normandy (then under English rule) |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church Anglican Communion[3] |

| Beatified | 18 April 1909, St. Peter's Basilica by Pope Pius X |

| Canonized | 16 May 1920, St. Peter's Basilica by Pope Benedict XV |

| Feast | 30 May |

| Patronage | France; martyrs; captives; military personnel; people ridiculed for their piety; prisoners; soldiers, women who have served in the WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service); and Women's Army Corps |

Joan of Arc (1412–1431) was formally recognized as a saint of the Roman Catholic Church in 1920, concluding the canonization process which the Sacred Congregation of Rites instigated after an 1869 petition of the French Catholic hierarchy. Although pro-English clergy had Joan burnt at the stake for heresy in 1431, she was rehabilitated in 1456 after a posthumous retrial. Subsequently she became a folk saint among French Catholics and soldiers inspired by her story of being commanded by God to fight for France against England. Many French regimes encouraged her cult, and the Third Republic was sympathetic to the canonization petition prior to the 1905 separation of church and state.

Path to sainthood

Death and 15th century

As with other saints who were excommunicated or investigated by ecclesiastic courts, such as Athanasius, Teresa of Ávila, and John of the Cross, Joan was put on trial by an Inquisitorial court. In her case, the court was influenced by the English, which occupied northern France, leading to her execution in the marketplace of Rouen. When the French retook Rouen in 1449, a series of investigations were launched. Her now-widowed mother Isabelle Romée and Joan's brothers Jéan and Pierre, who were with Joan at the Siege of Orleans, petitioned Pope Nicholas V to reopen her case. The formal appeal was conducted in 1455 by Jean Bréhal, Inquisitor-General of France, under the aegis of Pope Callixtus III. Isabelle addressed the opening session of the appellate trial at Notre Dame with an impassioned plea to clear her daughter's name. Joan was exonerated on July 7, 1456, with Bréhal's summary of case evidence describing her as a martyr who had been executed by a court which itself had violated Church law. [4] In 1457, Callixtus excommunicated the now-deceased Bishop Pierre Cauchon for his persecution and condemnation of Joan. [5]

The city of Orléans had commemorated her death each year beginning in 1432, and from 1435 onward performed a religious play centered on the lifting of the siege. The play represented her as a divinely-sent savior guided by angels. In 1452, during one of the postwar investigations into her execution, Cardinal d'Estouteville declared that this play would merit qualification as a pilgrimage site by which attendees could gain an indulgence.

Not long after the appeal, Pope Pius II wrote an approving piece about her in his memoirs.

16th century

Joan was utilized as a symbol of the Catholic League, a group organized to fight against Protestant groups during the Wars of Religion. An anonymous author wrote a biography of Joan's life, stating that it was compiled "By order of the King, Louis XII of that name" in circa 1500. [6]

17th century

Edmond Richer's La premiére histoire en date de Jeanne d'Arc: histoire de la Pucelle d'Orléans (1625-1630) is not published until 1911 by Henri and Jules Desclée. [7]

18th and 19th centuries

Joan's cult of personality was opposed by the leaders of the French Revolution as she was a devout Catholic who had served the monarchy. They banned the yearly celebration of the lifting of the siege of Orleans, and Joan's relics, including her sword and banner, were destroyed. A statue of Joan erected by the people of Orléans in 1571 (to replace one destroyed by Protestants in 1568) was melted down and made into a cannon. [8]

Recognizing he could use Joan for his nationalist purposes, Napoleon allowed Orléans to resume its yearly celebration of the lifting of the siege, commissioned Augustin Dupré to strike a commemorative coin, [9] [10] and had Jean-Antoine Chaptal inform the mayor of Orléans that he approved of a resolution by the municipal council for Edme-François-Étienne Gois to erect his statue of Joan:

"The illustrious career of Joan of Arc proves that there is no miracle French genius cannot perform in the face of a threat against national freedom." [11] [12]

Gois's work was relocated to Place Dauphiné in 1855, [13] replaced with a statue of Joan by Denis Foyatier. [14]

Although Nicolas Lenglet Du Fresnoy and Clément Charles François de Laverdy are credited with the first full-length biographies of Joan, several English authors ironically sparked a movement which lead to her canonization. Harvard University English literature professor Herschel Baker noted in his introduction to Henry VI for The Riverside Shakespeare how appalled William Warburton was by the depiction of Joan in Henry VI, Part 1, and that Edmond Malone sought in "Dissertation on the Three Parts of Henry VI" (1787) to prove Shakespeare had no hand in its authorship (1974; p. 587). Charles Lamb chided Samuel Taylor Coleridge for reducing Joan to "a pot girl" in the first drafts of The Destiny of Nations, initially part of Robert Southey's Joan of Arc. She was the subject of essays by Lord Mahon for The Quarterly Review, [15] and by Thomas De Quincey for Tait's. [16] In 1890, the Joan of Arc Church was dedicated to her.

As Joan found her way further into popular culture, the Government of France commissioned Emmanuel Frémiet to erect a statue of her in the Place des Pyramides -- the only public commission of the state from 1870 to 1914. The French Navy dedicated four vessels to her: a 52-gun frigate (1820); a 42-gun frigate (1852); an ironclad corvette warship (1867); and an armored cruiser (1899). Philippe-Alexandre Le Brun de Charmettes's biography (1817), and Jules Quicherat's account of her trial and rehabilitation (1841-1849) seemed to have inspired canonization efforts. In 1869, Bishop Félix Dupanloup and 11 other bishops petitioned Pope Pius IX to have her canonized, but the Franco-Prussian War postponed further action. In 1874, depositions began to be collected, received by Cardinal Luigi Bilio in 1876 (same year as Henri-Alexandre Wallon's biography). Dupanloup's successor, Bishop Pierre-Hector Coullié, directed an inquest to authenticate her acts and testimony from her trial and rehabilitation. On January 27, 1894, the Curia (Cardinals Benedetto Aloisi-Masella, Angelo Bianchi, Benoît-Marie Langénieux, Luigi Macchi, Camillo Mazzella, Paul Melchers, Mario Mocenni, Lucido Parocchi, Fulco Luigi Ruffo-Scilla, and Isidoro Verga) voted unanimously that Pope Leo XIII sign the Commissio Introductionis Causæ Servæ Dei Joannæ d'Arc, which he did that afternoon. [17] [18] [19]

20th century to present

However, the path to sainthood did not go smoothly. On August 20, 1902, the Papal consistory rejected adding Joan to the Calendar of saints, citing: she launched the assault on Paris on the birthday of Mary, mother of Jesus; her capture ("proof" her claim that she was sent by God was false); her attempts to escape from prison; her abjure after being threatened with death; and doubts of her purity. [20] [21] On November 17, 1903, the Sacred Congregation of Rites met to discuss Joan's cause at the behest of Pope Pius X. [22] [23] A decree proclaiming Joan's heroic virtue was issued on January 6, 1904 by Cardinal Serafino Cretoni, [24] and Pius proclaimed her venerable on January 8. [25] The Decree of the Three Miracles was issued on December 13, 1908, and The Decree of Beatification was read five days later, which was issued formally by the Congregation of Rites on January 24, 1909. [26] [27]

The Beatification ceremony was held on April 18, 1909, presided by Cardinals Sebastiano Martinelli and Mariano Rampolla. Bishop Stanislas Touchet performed the Mass. Cardinals Serafino Vannutelli, Pierre Andrieu, Louis Luçon, Coullié, Girolamo Maria Gotti, José Calassanç Vives y Tuto, then-Monsignor Rafael Merry del Val, [28] Bishop John Patrick Farrelly, Bishop Thomas Kennedy, Monsignor Robert Seton, Count Giulio Porro-Lambertenghi (grandson of Luigi Porro Lambertenghi) with tribunes from The Knights of Malta, The Duke of Alençon and The Duke of Vendôme, then-Archbishop William Henry O'Connell, [29] and The Duke of Norfolk [30] attended. Pius - who was determined that the ceremony would not be used by Legitimists to attack the Third Republic [31] - venerated the relics that afternoon, flanked by 70 French Prelates. [32]

Her beatification approximately coincided with the French invention of the Janvier transfer engraving machine (also called a die engraving pantograph), which facilitates the creation of minted coins and commemorative medallions. This invention, together with the already well-established French sculptural tradition, added another element to Joan's beatification: a series of well-made religious art medals featuring scenes from her life.

In the subsequent fighting during World War I, French troops carried her image into battle with them. During one battle, they interpreted a German searchlight image projected onto low-lying clouds as an appearance by Joan, which bolstered their morale greatly. [see: The Maid of Orléans: The Story of Joan of Arc Told to American Soldiers by Charles Saroléa, Georges Crès & Cie (1918)]

Her canonization was held on May 16, 1920. Over 60,000 people attended the ceremony, including 140 descendants of Joan's family. Dignitaries included: Vendôme, Lambertenghi with The Knights of Malta, now-Bishop O'Connell, Gabriel Hanotaux, Princess Zinaida Yusupova, Princess Irina Alexandrovna, Prince Feodor Alexandrovich, The Duke of Braganza, The Count de Salis-Soglio, Rafael Valentín Errázuriz, Diego von Bergen, Bishop John Patrick Carroll, Archbishop Edward Joseph Hanna, Bishop Daniel Mary Gorman, Bishop Paul Joseph Nussbaum, the student body of The American College of Rome, and now-Cardinal Merry del Val, who greeted Pope Benedict XV as Benedict entered St. Peter's Basilica to preside over the rites. One-hundred thousand people celebrated at Westminster Cathedral, and at French churches throughout London. [33] [34] [35] [36] [37]

In the May 18, 1920 Le Matin, former President of France Raymond Poincaré wrote that Joan's canonization "fulfills the last part of her mission in bringing together forever in the sacredness of her memory" one-time mortal enemies England and France: "In her spirit, let us remain united for the good of Mankind". [38]

Popularity

Joan of Arc's feast day is 30 May. Although reforms in 1968 moved many medieval European saints' days off the general calendar in order to make room for more non-Europeans, her feast day is still celebrated on many local and regional Church calendars, especially in France. Many Catholic churches around the globe have been named after her in the decades since her canonization.

She has become especially popular among Traditional Catholics, particularly in France - both because of her obvious connection to this country as well as the fact that the Traditional Catholic movement is strongest there. This branch of Catholicism, which has refused to accept the changes made by the Second Vatican Council, has compared the 1988 excommunication of Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre (one of the founders of the Traditional Catholic movement) to Joan of Arc's excommunication by a corrupt pro-English bishop in 1431. Traditional Catholic parishes sometimes perform plays in Joan of Arc's honor.[citation needed]

Notes

- ^ (See Pernoud's Joan of Arc By Herself and Her Witnesses, p. 98: "Boulainvilliers tells of her birth in Domrémy, and it is he who gives us an exact date, which may be the true one, saying that she was born on the night of Epiphany, 6 January").

- ^ "Chemainus Theatre Festival > The 2008 Season > Saint Joan > Joan of Arc Historical Timeline". Chemainustheatrefestival.ca. Archived from the original on 2013-06-02. Retrieved 2012-11-30.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Church of England Holy Days

- ^ Pernoud, Regine. "Joan of Arc by Herself and Her Witnesses". Scarborough House, 1994; pp 268-269.

- ^ Reviews: Le Martyre de Jéanne d'Arc by Léo Taxil The Tablet Vol. 75; No. 2616 (June 28, 1890), pps. 1010-1011 Google Books December 30, 2016

- ^ The First Biography of Joan of Arc: Translated and Annotated by Daniel Rankin and Claire Quintal University of Pittsburgh Press (1964) Google Books April 2, 2017

- ^ "Edmond Richer (1560-1631)" Post-Reformation Digital Library March 25 2017

- ^ "The Maid of Orléans" by Andrew Lang The English Illustrated Magazine Vol. 16 (October 1896-March 1897), pps. 315-320 Google Books March 25, 2017

- ^ "1803 France - Napoleon - The Monument of Joan of Arc by Augustin Dupré" VHobbies.com March 25, 2017

- ^ "Monuments" Memoirs of Jeanne d'Arc, Vol. 2; J. Moyes, London (1824), p. cclxxvi Google Books March 25, 2017

- ^ "To Citizen Chaptal" Napoleon Self-Revealed ed. by J.M. Thompson Houghton Mifflin (1934); reprinted as Napoleon's Letters (2013), p. 67 Google Books March 28, 2017

- ^ "Report Made to the Athénée des Arts de Paris by MM. Rondelet, Beauvallet, and Duchesne on the Founding the Statue of Joan of Arc in Bronze, by a Way Never Before Used for Large Works, by MM. Rousseau and Genon, Under the Direction of M. Gois" Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry, and the Arts Vol. 13 (1806), pps. 128-135 Google Books March 25, 2017

- ^ "Orleans: Jeanne d'Arc guerrière" vanderkrogt.net March 25, 2017

- ^ "Orleans: Jeanne d'Arc" vanderkrogt.net March 25, 2017

- ^ Joan of Arc: Reprinted From Lord Mahon's Historical Essays John Murray (1853) Google Books January 20, 2017

- ^ "Selections" English Classic Series #69; Maynard, Merrill & Co. (1892), pps. 9-41 Google Books January 20, 2017

- ^ "The Beatification of Joan of Arc" The Literary Digest (March 1, 1894) Vol. VIII; No. 18, pps. 22-23 Google Books March 27, 2017

- ^ The Saints: Joan of Arc by Louis Petit de Julleville (1901) Duckworth & Co. pps. 185-191 Google Books February 24, 2017

- ^ "Appendix: D. The Proposed Canonization of Joan of Arc" Joan of Arc by Francis Cabot Lowell (1896) Houghton Mifflin Company pps. 372-373 Google Books December 6, 2016

- ^ "Was Not Made a Saint: Why Consistory Refused to Canonize Joan of Arc" Indianapolis Journal (September 7, 1902), p. 12 newspapers.library.in.gov March 25, 2017

- ^ "Joan of Arc Not to be Canonized" Harper's Weekly (April 11, 1903) Vol. XLVII; No. 2416, p. 610 Google Books March 25, 2017

- ^ "Editorial Notes" The Sacred Heart Review Boston College (October 3, 1903) Vol. 30; No. 14, p. 5 newspapers.bc.edu March 26, 2017

- ^ "Notes" The Tablet (November 28, 1903) Vol. 102; No. 3316, p. 845 Google Books March 26, 2017

- ^ "Joan of Arc - Her Heroic Virtue: Text of the Decree" The Tablet (January 16, 1904) Vol. 103; No. 3323, pps. 88-89 Google Books March 26, 2017

- ^ Life of His Holiness Pope Pius X by Josef Schmidlin and Anton de Waal (1904) Benziger Brothers, p. 392 Google Books March 26, 2017

- ^ "The Blessed Joan of Arc" by Bishop Thomas James Conaty The West Coast Magazine Vol. 7; No. 6. (March 1910), pps. 737-745 Google Books March 25, 2017

- ^ "Blessed Joan of Arc. Reading of the Decree of the French Heroine" Montreal Gazette (December 19, 1908), p. 14 Google News Archive August 3, 2016

- ^ "The Spectator" The Outlook (July 3, 1909) Vol. 92, pps. 548-550 Google Books May 19, 2016

- ^ "Pilgrims Honor Maid of Orleans" The Daily Republican (April 19, 1909), p. 2 Google News Archive February 24, 2017

- ^ "The Beatification of Joan of Arc" The Age (April 20, 1909) via The Kilmore Free Press (June 24, 1909) p. 1 Trove February 24, 2017

- ^ "The Beatification of Joan of Arc" Current Literature vol. XLVI no. 6 (June 1909) pps. 601-603 Google Books June 21, 2017

- ^ "The Maid of Orleans: Joan of Arc Beatified and The Pope Venerates the Relics" Montreal Gazette (April 19, 1909), p. 4 Google News Archive October 18, 2016

- ^ "Maid of Orleans is Made a Saint" The Toronto World (May 17, 1920), p. 11 Google News Archive May 19, 2016

- ^ "Joan of Arc is Decalred Saint in Ceremony by Church at Rome" The Bakersfield Californian (May 17, 1920), p. 2 Google News Archive May 19, 2016

- ^ "Impressive Ceremonies Used in Canonizing Joan of Arc" The Deseret News (May 17, 1920), p. 8 Google News Archive May 19, 2016

- ^ "Joan of Arc is Exalted by Pope" Telegraph-Herald (May 17, 1920), pps. 1,8 Google News Archive May 21, 2016

- ^ "Remarkable Scene: 100,000 Watched Great War Pageant in London" Montreal Gazette (May 17, 1920), p. 1 Google News Archive May 22, 2016

- ^ "Mission is Fulfilled: Spirit of Joan of Arc Unites Britain and France" Edwin L. James Montreal Gazette (May 17, 1920), p. 1 Google News Archive May 22, 2016

References

"Joan of Arc Made a Saint". Associated Press. 1920-05-16.

External links

- Catholic Encyclopedia entry for St. Joan of Arc.

- Médailles Jeanne d’Arc.French site containing pictures and descriptions of Medallions devoted to Joan of Arc.