Carbene

In chemistry, a carbene is a organic molecule containing a carbon atom with six valence electrons and having the general formula RR'C:.[1] Carbenes are classified into two varieties, singlets and triplets. Most carbenes are very short lived, although persistent carbenes are known.

The prototypical carbene is H2C: also called methylene. One well studied carbene is Cl2C:, or dichlorocarbene, which can be generated in situ from chloroform and a strong base.

Structure and bonding

The two classes of carbenes are singlet and triplet carbenes. Singlet carbenes are spin-paired. In the language of valence bond theory, The molecule adopts an sp2 hybrid structure. Triplet carbenes have two unpaired electrons. They may be either linear or bent, i.e. sp2 sp hybridized. Most carbenes have a nonlinear triplet ground state, except for those with nitrogen, oxygen, or sulfur atoms, and halides directly bonded to the divalent carbon.

Carbenes are called singlet or triplet depending on the electronic spins they possess. Triplet carbenes are paramagnetic and may be observed by electron spin resonance spectroscopy if they persist long enough. The total spin of singlet carbenes is zero while that of triplet carbenes is one (in units of ). Bond angles are 125-140° for triplet methylene and 102° for singlet methylene (as determined by EPR). Triplet carbenes are generally stable in the gaseous state, while singlet carbenes occur more often in aqueous media.

For simple hydrocarbons, triplet carbenes usually have energies 8 kcal/mol (33 kJ/mol) lower than singlet carbenes (see also Hund's rule of Maximum Multiplicity), thus, in general, triplet is the more stable state (the ground state) and singlet is the excited state species. Substituents that can donate electron pairs may stabilize the singlet state by delocalizing the pair into an empty p-orbital. If the energy of the singlet state is sufficiently reduced it will actually become the ground state. No viable strategies exist for triplet stabilization. The carbene called 9-fluorenylidene has been shown to be a rapidly equilibrating mixture of singlet and triplet states with an approximately 1.1 kcal/mol (4.6 kJ/mol) energy difference.[2]. It is however debatable whether diaryl carbenes such as the fluorene carbene are true carbenes because the electrons can delocalize to such an extent that they become in fact biradicals. In silico experiments suggest that triplet carbenes can be stabilized with electropositive groups such as trifluorosilyl groups [3].

Reactivity

Singlet and triplet carbenes exhibit divergent reactivity. Singlet carbenes generally participate in cheletropic reactions as either electrophiles or nucleophiles. Singlet carbenes with unfilled p-orbital should be electrophilic. Triplet carbenes can be considered to be diradicals, and participate in stepwise radical additions. Triplet carbenes have to go through an intermediate with two unpaired electrons whereas singlet carbene can react in a single concerted step.

Due to these two modes of reactivity, reactions of singlet methylene are stereospecific whereas those of triplet methylene are stereoselective. This difference can be used to probe the nature of a carbene. For example, the reaction of methylene generated from photolysis of diazomethane with cis-2-butene or with trans-2-butene each give a single diastereomer of the 1,2-dimethylcyclopropane product: cis from cis and trans from trans, which proves that the methylene is a singlet.[4] If the methylene were a triplet, one would not expect the product to depend upon the starting alkene geometry, but rather a nearly identical mixture in each case.

Reactivity of a particular carbene depends on the substituent groups. Their reactivity can be affected by metals. Some of the reactions carbenes can do are insertions into C-H bonds, skeletal rearrangements, and additions to double bonds. Carbenes can be classified as nucleophilic, electrophilic, or ambiphilic. For example, if a substituent is able to donate a pair of electrons, most likely carbene will not be electrophilic. Alkyl carbenes insert much more selectively than methylene, which does not differentiate between primary, secondary, and tertiary C-H bonds.

Carbenes add to double bonds to form cyclopropanes. A concerted mechanism is available for singlet carbenes. Triplet carbenes do not retain stereochemistry in the product molecule. Addition reactions are commonly very fast and exothermic. The slow step in most instances is generation of carbene. A well-known reagent employed for alkene-to-cyclopropane reactions is Simmons-Smith reagent. This reagents is a system of copper, zinc, and iodine, where the active reagent is believed to be iodomethylzinc iodide. Reagent is complexed by hydroxy groups such that addition commonly happens syn to such group.

Insertions are another common type of carbene reactions. The carbene basically interposes itself into an existing bond. The order of preference is commonly: 1. X-H bonds where X is not carbon 2. C-H bond 3. C-C bond. Insertions may or may not occur in single step.

Intramolecular insertion reactions present new synthetic solutions. Generally, rigid structures favor such insertions to happen. When an intramolecular insertion is possible, no intermolecular insertions are seen. In flexible structures, five-membered ring formation is preferred to six-membered ring formation. Both inter- and intramolecular insertions are amendable to asymmetric induction by choosing chiral ligands on metal centers.

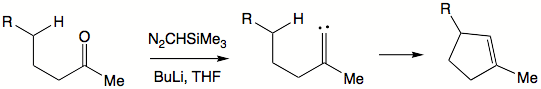

Alkylidene carbenes are alluring in that they offer formation of cyclopentene moieties. To generate an alkylidene carbene a ketone can be exposed to trimethylsilyl diazomethane.

Carbenes ligands in organometallic chemistry

In organometallic species, metal complexes with the formulae LnMCRR' are often described as carbene complexes. Such species do not however react like free carbenes and are rarely generated from carbene precursors, except for the persistent carbenes. The transition metal carbene complexes can be classified according to their reactivity, with the first two classes being the most clearly defined:

- Fischer carbenes, in which the carbene is bonded to a metal that bears an electron-withdrawing group (usually a carbonyl). In such cases the carbenoid carbon is mildly electrophilic.

- Schrock carbenes, in which the carbene is bonded to a metal that bears an electron-donating groups. In such cases the carbenoid carbon is nucleophilic and resembles Wittig reagent (which are not considered carbene derivatives).

- Persistent carbenes, also known as Arduengo or Wanzlick carbenes. These include the class of N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs) and are often are used as ancillary ligands in organometallic chemistry. Such carbenes are spectator ligands of low reactivity.

Generation of carbenes

- Most commonly, photolytic, thermal, or transition metal catalyzed decomposition of diazoalkanes is used to create carbene molecules. A variation on catalyzed decomposition of diazoalkanes is the Bamford-Stevens reaction, which gives carbenes in aprotic solvents and carbenium ions in protic solvents.

- Another method is induced elimination of halogen from gem-dihalides or HX from CHX3 moiety, employing organolithium reagents (or another strong base). It is not certain that in these reactions actual free carbenes are formed. In some cases there is evidence that completely free carbene is never present. It is likely that instead a metal-carbene complex forms. Nevertheless, these metallocarbenes (or carbenoids) give the expected products.

- Photolysis of diazirines and epoxides can also be employed. Diazirines contain 3-membered rings and are cyclic forms of diazoalkanes. The strain of the small ring makes photoexcitation easy. Photolysis of epoxides gives carbonyl compounds as side products. With asymmetric epoxides, two different carbonyl compounds can potentially form. The nature of substituents usually favors formation of one over the other. One of the C-O bonds will have a greater double bond character and thus will be stronger and less likely to break. Resonance structures can be drawn to determine which part will contribute more to the formation of carbonyl. When one substituent is alkyl and another aryl, the aryl-substituted carbon is usually released as a carbene fragment.

- Thermolysis of alpha-halomercury compounds is another method to generate carbenes.

- Rhodium and copper complexes promote carbene formation.

- Carbenes are intermediates in the Wolff rearrangement

Applications of carbenes

A large scale application of carbenes is the industrial production of tetrafluoroethylene, the precursor to Teflon. Tetrafluoroethylene is generated via the intermediacy of difluorocarbene:[5]

- CHClF2 → CF2 + HCl

- 2 CF2 → F2C=CF2

See also

- Transition metal carbene complex also known as carbenoids

- Atomic carbon a single carbon atom with chemical formula :C:, in effect a dicarbene. Also has been used to make "true carbenes" in situ.

- Foiled carbenes derive their stability from proximity of a double bond (i.e their ability to form conjugated systems).

References

- ^ Organic Chemistry R.T Morrison, R.N Boyd pp 473-478.

- ^ Chemical and Physical Properties of Fluorenylidene: Equilibrium of the Singlet and Triplet Carbenes Peter B. Grasse, Beth-Ellen Brauer, Joseph J. Zupancic, Kenneth J. Kaufmann, Gary B. Schuster; J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 1983; 105; 6833-6845.

- ^ Electronic Stabilization of Ground State Triplet Carbenes Adelina Nemirowski and Peter R. SchreinerJ. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 9533-9540 9533 doi:10.1021/jo701615x

- ^ "Structure of Carbene CH2". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 78 (17): 4496–4497. 1956. doi:10.1021/ja01598a087.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ William X. Bajzer "Fluorine Compounds, Organic," Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 2004. doi:10.1002/0471238961.0914201802011026.a01.pub2